After Waterloo and the dispatch of Napoleon Bonaparte to St. Helena, the Congress of Vienna redrew the map of Germany. The three hundred German kingdoms, electorates, principalities, grand duchies, bishoprics, and free cities which had made up the old Holy Roman Empire, bound by lip service to the Hapsburg Emperor in Vienna, were reconstituted into a loose confederation of thirty-nine states. Most remained small, a few were tiny, and there were five sovereign kingdoms: Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, Hanover, and Württemberg. A Federal Diet to which all states sent representatives was established in the free city of Frankfurt on the Main. Its purpose was to settle disputes between the German states and, above all, to preserve the conservative status quo. In Germany and in the Diet, Austria—strictly speaking, not a German power at all—remained predominant. She possessed the prestige of an imperial ruler, the skillful diplomacy of the post-Napoleonic era’s dominant statesman, Prince Clemens von Metternich, and the largest army in Central Europe.

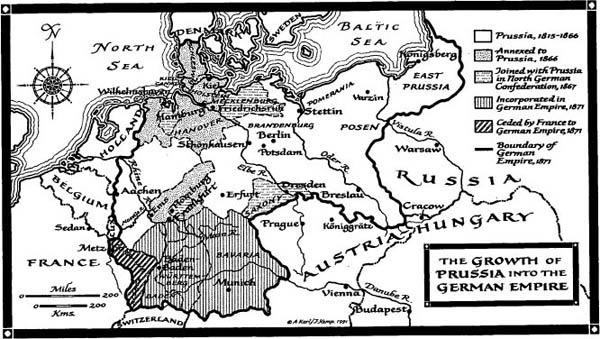

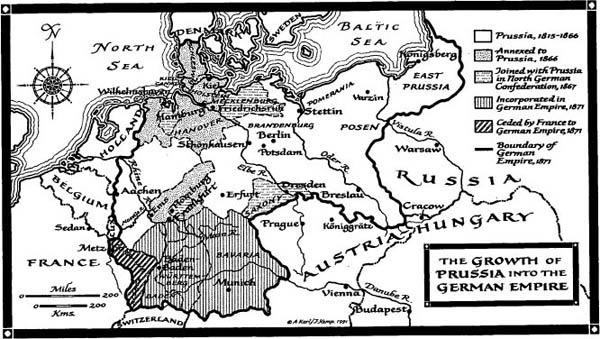

Prussia, largest and strongest of the purely German states, was approaching Great Power status. Blücher’s Prussians had relieved Wellington’s exhausted army and turned the tide at Waterloo. The Congress of Vienna had added significant territories in the Rhineland and Westphalia to the Prussian Kingdom and the black and white flag with the Prussian double eagle now flew from Aachen and Coblenz to Königsberg near the Russian frontier. The new lands in the west, among the most densely populated in Germany, were heavily Roman Catholic, and rich in mineral wealth and industrial potential. One of the King of Prussia’s newly acquired subjects was the ironmaster of Essen, Friedrich Krupp. The Prussian state, traditionally Protestant, overwhelmingly rural, with its Spartan military tradition, nevertheless remained inferior to Austria in one essential ingredient of national power: population. In 1815, there were 10 million Prussians, compared to 30 million Frenchmen and 30 million subjects of the Austrian emperor.

Through the first half of the nineteenth century, the drive towards German unification gained momentum, speeded by the growth of industry and railways. In 1834, a Prussian-organized customs union (Zollverein) lowered tariff barriers; in the 1850s, a doubling of trackage in the German railway network brought all German states within hours of one another. Coal mined in the Saar and in Silesia heated industrial furnaces in the Ruhr. The ports of Bremen and Hamburg exported and imported goods for the whole of Germany. Yet fifty years after the Congress of Vienna, Germany remained a loose political confederation of thirty-nine states. Austria, continuing to dominate the Federal Diet in Frankfurt, opposed any change; France, again risen to primacy in Europe under a new Emperor, Napoleon III, reinforced Austria’s policy. The statesman who changed this—who expelled Austria from Germany, defeated France and toppled Napoleon III, unified Germany, created the German Empire, and transferred the capital of Continental Europe from Paris or Vienna to Berlin—was Otto von Bismarck.

For twenty-eight years (1862–1890), the greatest German political figure since the Middle Ages loomed over Germany and Europe. Bismarck’s very appearance created an image of force and intimidation. Over six feet tall, with broad shoulders, a powerful chest, and long legs, he gave up wearing civilian frock coats when he became Imperial Chancellor and appeared only in military uniform: Prussian blue tunic, spiked helmet, and long black cavalry boots which extended over the thigh. The top of his head was bald before he reached fifty, but thick hair continued to sprout and tumble over his ears, in bushy eyebrows, and in a heavy bushy mustache. The eyes, wide apart and heavily pouched, glittered with intelligence and flashed with authority. Despite the aura of power surrounding this huge frame, there were contradictions: Bismarck’s hands and feet were small, even delicate; his waist, before it turned to paunch, was abnormally narrow; his voice was not the deep bass or resonant baritone one might expect—it was a thin, high, reedy, almost piping tenor.

Bismarck’s character was equally complex and contradictory. His greatest gift was intelligence; he possessed intellectual ascendancy over all the politicians of his time, German or European, and all—German and European—acknowledged this. He was self-confident, even daring, to the point of recklessness. He combined indomitable will and tenacity of purpose in reaching long-range goals with resourcefulness, suppleness, and virtuosity in improvising means. Bismarck was willing to work indefatigably, with exuberant energy, to create political and diplomatic situations from which he could profit; he was equally ready to seize an unexpected prize suddenly offered. His manner could be genial and charming; subordinates and enemies more often saw cunning, ruthlessness, unscrupulousness, brutality, and cruelty. Underneath, not surprisingly, lay restlessness, anger, myriad grievances, jealousy, and pettiness. Bismarck’s politics and diplomacy were based on practical experience and he disdained theorists and sentimentalists. Near the end of his career, he was moody, suspicious, and misanthropic, bowed by the endlessly complicated business of governing. In Germany, he had no friends or colleagues, only subordinates. His assistant at the Foreign Ministry, Friedrich von Holstein, said that Bismarck treated people “not as friends, but as tools, like knives and forks,1 which are changed after each course.”

Not all Germans approved of Bismarck. German liberals had fought for national unity, but they had wanted to achieve it in a democratic, parliamentary form, not have it thrust upon the nation by a powerful, conservative statesman wielding the power of a primitive, disciplined military state. Nevertheless, Bismarck had his way. He was the strongest personality and the most powerful political force Europe had known since Napoleon I. From the moment in 1862 when King William I of Prussia reluctantly made the Junker diplomat his Minister-President, Germany and Europe entered the Age of Bismarck.

Otto von Bismarck was born on April 1, 1815, two and a half months before the Battle of Waterloo, in Schönhausen in Prussia, near the Elbe River west of Berlin. His father, Ferdinand, a minor nobleman, possessed a typical Junker estate with cattle, sheep, wheatfields, and timber. The Junkers, whose nearest approximation was the rough English country squirearchy, lived close to the land, often milking their own cows, running their own sawmills, and selling their own wool at market. Although they worked their estates, they were proud of their ancient lineage. Bismarck sprang from a family older in Prussia than the Hohenzollerns, who had come from Stuttgart in 1415; Prussia’s kings, Bismarck once said, derive from “a Swabian family2 no better than mine.” Most Junkers were pious, rigid, and frugal, devoted to the land, to the Protestant church, and to their monarch, whose army they officered and government they administered. They cared nothing for the rest of the world and little for the rest of Germany; Bismarck himself never regarded South Germans or Catholic Germans as true Germans. Junkers were not interested in the great capitals of Europe: Paris, Vienna, and London. If they looked beyond their villages at all, it was to Berlin, the growing capital of their Spartan military state.

Ferdinand von Bismarck was a dull, easygoing Junker who managed his estate with only modest success. His wife, Wilhelmine, was a personality of striking contrast. The daughter of Ludwig Mencken, the trusted counselor of Frederick the Great, she had been brought up in Berlin, where she eagerly absorbed everything the capital had to offer. Her father died when she was nine and, in gratitude for his services, the royal family took Wilhelmine in hand and brought her up with the Hohenzollern children. Her marriage at sixteen to the ponderous, rustic nobleman over twice her age was considered a sound match—she was a commoner—but it was a mistake. Marooned on a farm, she compensated by ignoring her husband and concentrating on her children. She encouraged intelligence, ambition, restlessness, and energy, but gave little affection. At six, Otto was dispatched to school in Berlin, where he remained until he was sixteen. He grew up a strange mixture of his dissimilar parents: a tall, increasingly bulky boy, with a highly educated, tempestuous, romantic, passionate nature, bursting with strength and determination. In the words of a biographer, “he was the clever, sophisticated son3 of a clever, sophisticated mother masquerading all his life as his heavy, earthy father.”

At seventeen, Bismarck enrolled at Göttingen University, the most famous liberal institution in Germany. There, he rejected contact with liberal, middle-class students, joined an aristocratic student society, drank exuberantly, neglected his studies, and, some say, fought twenty-five duels. He wore outrageous, varicolored clothes, challenged university discipline, and read Schiller, Goethe, Shakespeare, and Byron, preferring the English writers to the German. (His favorite author was Sir Walter Scott, whose novels stirred history into romance.) At Göttingen, Bismarck made a close friend of the American future historian John Motley, whose famous Rise of the Dutch Republic was to become a monument of nineteenth-century scholarship. Forty years later, as Imperial Chancellor, Bismarck often wrote to “Dear old John” and would happily abandon the duties of office to make Motley welcome.

Two years at Göttingen and a third at the University of Berlin equipped Bismarck for the entrance exams of the Prussian Civil Service. The tall young man’s first assignment was to the city of Aachen in the western Rhineland. In 1836, when Bismarck arrived, the Catholic, free-thinking city was still disgruntled at having been handed over by the Congress of Vienna to Prussia. But the city’s reputation as a spa still brought pleasure seekers from many nations, especially England. Bismarck, twenty-one, plunged into this urbane society, indulging happily in drink, gambling, and debt. He discovered the charms of well-born young Englishwomen and fell in love with Isabella Lorraine-Smith, the daughter of a fox-hunting parson from Leicester. When Isabella and her parents moved on to Wiesbaden, Bismarck took two weeks’ leave to accompany them. In Wiesbaden, he spent extravagantly on midnight champagne suppers and, when she left for Switzerland, he followed. At the end of two months, when he wrote to his superior in Aachen that he would be absent for some additional time, he was suspended. The result did not trouble Bismarck. He “by no means intended4 to give the government an account of his personal relations,” he said. A few weeks later, he was back at his family farm, his job terminated, his affair with Isabella over, but his knowledge of English greatly improved.

Bismarck returned to Berlin and endured one year of required military service in a regiment of Foot Guards. When he was twenty-four, his mother died and he resigned from the Civil Service to assist his father, who was ineffectually administering an estate in Pomerania. For eight long years while Otto and his brother Bernhard labored to restore the property to prosperity, the tempestuous youth with his romantic temper was chained to the barren life of a Pomeranian Junker. He found estate management, conversations with peasants, and the society of his Junker neighbors boring. Frustration turned to frenzy and the countryside rang with tales of the reckless, hard-drinking young landowner. He was said to ride hallooing through the night, to be ready to shoot, hunt, or swim anywhere in any weather, to be able to drink half a dozen young lieutenants from nearby garrisons under the table, to wake up his occasional guests by firing a pistol through their bedroom windows, to have seduced every peasant girl in all the villages, to have released a fox in a lady’s drawing room. At the same time, he read hungrily, steeping himself in history and devouring English novels such as Tom Jones and Tristram Shandy. Mired in farm life, he thirsted for some noble or heroic purpose. Yet despite his boredom, there was a side of Bismarck’s nature that loved the life of a Junker squire: the possession of land; riding or walking under his great trees. At twenty-seven, in the middle of these years, Bismarck made a three-month visit to Britain, passing through Edinburgh, York, Manchester, London, and Portsmouth. He liked England and, for a moment, toyed with the idea of joining the British Army in India. The impulse died when “I asked myself what harm the Indians had done me,”5 he said later. In 1844, at twenty-nine, Bismarck’s frustration drove him to reenter the Prussian Civil Service: he resigned two weeks later, explaining, “I have never been able to put up with superiors.”6

To steady himself, he married Johanna von Puttkamer, the daughter of another Pomeranian Junker. Simple, modest, patient, devoted, and ready to endure any behavior from the unstable, emotional volcano who was her husband, Johanna shared his opinion that wives belonged exclusively in the domestic sphere. “I like piety7 in a woman and abhor all feminine cleverness,” he told his brother. Later, Johanna did not read his speeches even when the whole of Germany and all of Europe were discussing them. Her understanding of politics was personal: she was a friend of her husband’s friends, she disliked or hated his opponents. When she married at twenty-three, Johanna von Puttkamer was not beautiful, but she possessed arresting dark eyes and a wealth of long, fine, black hair. She played the piano well and her playing of Beethoven’s “Sonata Appassionata,” Bismarck’s favorite piece, could reduce her husband to tears. Bismarck wooed her mostly by talking about himself. Before their betrothal in February 1847, he wrote to her, “On a night like this8 I feel uncommonly moved myself to become a sharer of delight, a portion of the tempest and of night, and, mounted on a runaway horse, to hurl myself over the cliff into the foam and fury of the Rhine, or something similar.” He had enough control, however, to add wryly, “A pleasure of that kind, unfortunately, one can enjoy but once in life.”

Eighteen forty-eight was the Year of Revolution. France rose against the restored Bourbon monarchy and drove away King Louis Philippe; Metternich, the dominant figure at the Congress of Vienna, fled from Austria to England; Czechs, Magyars, and Italians rose in revolt. When revolutionary crowds filled the streets of Berlin, Prussian generals pleaded with King Frederick William IV to let them unleash the army. Frederick William refused and the army withdrew from the capital. The King agreed to a constitution and an elected parliament, and created a civilian militia responsible for law and order. Bismarck at Schönhausen became hysterical at the idea of the King of Prussia in the hands of the mob. He spoke of raising an army of peasants to march on Berlin and rescue the King. He entered the capital and went to the Castle, where he was denied entry. He suggested to Prince William of Prussia, Frederick William’s brother, a lifelong army officer, that he succeed his brother and impose order; William refused. In the end, the army reoccupied Berlin without bloodshed. “We have been saved9 by the specifically Prussian virtues,” Bismarck said. “The old Prussian concepts of honor, loyalty, obedience, and courage inspire the army.... Prussians we are and Prussians we remain.” Nevertheless, the limited constitution and an elected assembly, the Landtag, remained.

In 1851, Prussia needed an ambassador to the new German Federal Diet at Frankfurt. No one much cared when it was given to Bismarck, considered by many to be a flamboyant reactionary from Prussia’s backwoods. In Frankfurt, the nearest thing to an international capital Germany possessed, the predominant power was Austria. Bismarck’s task was to make plain to the Austrians and to other German states that Prussia considered itself the equal in Germany of the Hapsburg Empire.

The Austrian representative, Count von Thun und Hohenstein, was an aristocrat who treated other members of the Diet as social inferiors. Bismarck bridled at Thun’s behavior. When he called on Thun for the first time, the Austrian casually received him in shirtsleeves. Bismarck quickly stripped off his own jacket, saying, “Yes, it is a hot day.”10 Traditionally, Thun was the only ambassador who smoked at meetings; Bismarck ended this when he pulled out his own cigar and asked Thun for a light.

Bismarck’s eight years in Frankfurt added polish to his character. In the patrician town with its rich traditions, historic wealth, and cosmopolitan atmosphere, he became a serious diplomat. He lived well, smoked Havana cigars, and drank a concoction called Black Velvet, a mixture of stout and champagne. In the summer of 1855, his American friend, Motley, visited the Bismarck household in Frankfurt. “It is one of those houses,”11 Motley wrote to his wife, “where everyone does as he likes.... Here are young and old, grandparents and children and dogs all at once, eating, drinking, smoking, piano playing and pistol shooting (in the garden), all going on at the same time. It is one of those establishments where every earthly thing that can be eaten and drunk is offered you—soda water, small beer, champagne, burgundy, or claret, are out all the time—and everybody is smoking the best Havanas every minute.” Beneath this chaotic bonhomie, Bismarck was evolving a coolly cynical approach to foreign policy. It had nothing to do with dynastic alliances or ethnic groupings. It concerned itself only with Prussia, its security and prosperity; every other state was a potential ally or enemy according to circumstance. “When I have been asked12 whether I was pro-Russian or pro-Western,” he wrote to a friend in Berlin, “I have always answered: I am Prussian and my ideal in foreign policy is total freedom from prejudice, independence of decision reached without pressure or aversion from or attraction to foreign states and their rulers. I have had a certain sympathy for England and its inhabitants, and even now I am not altogether free of it; but they will not let us love them, and as far as I am concerned, as soon as it was proved to me that it was in the interests of a healthy and well-considered Prussian policy, I would see our troops fire on French, Russians, English or Austrians with equal satisfaction.”

In 1857 King Frederick William suffered a severe stroke and a year later became hopelessly insane. His brother, Prince William, was appointed regent. Bismarck, after eight years in Frankfurt, was dispatched as Prussian Minister to St. Petersburg. Feeling isolated from Berlin, Germany, and Europe, he grumbled that he had been put “on ice.”13 “Bismarck receives no news14 from Berlin,” wrote an assistant at the German Embassy. “That is to say the Wilhelmstrasse [the Ministry of Foreign Affairs] simply does not write to him. They don’t like him there and they behave as though he does not exist. So he conducts his own political intrigues, does no entertaining, complains incessantly about the cost of living, sees very few people, gets up at 11 or 11:30 and sits about all day in a green dressing gown, not stirring except to drink.” Bismarck served four years in the city on the Neva. Although he was popular with Tsar Alexander II, who took him bear hunting, he avoided most social life.

When King Frederick William IV died childless in 1861, his brother succeeded as King William I. The new King was sixty-three, a tall, honest, decent soldier who cared only about the army. The Prussian parliament insisted on reducing the period of required military service from three years to two. William and his War Minister, General Albrecht von Roon, refused. The crisis extended over two years. Roon, who knew and admired Bismarck, proposed to the King that the Minister in Russia be brought home to fight the King’s battle in the assembly. William was reluctant and Bismarck, when the idea was proposed to him, agreed only on condition that he also be given charge of foreign policy. William refused. The double impasse—King versus parliament, King versus Bismarck—continued. Three times, in 1860, 1861, and 1862, Bismarck was offered the Minister-Presidency of Prussia without control of foreign affairs; three times, Bismarck declined. Nevertheless, William decided, just in case, to bring Bismarck closer and in May 1862 Bismarck was transferred from St. Petersburg to Paris. Bismarck, aware of the confused state of affairs in Berlin, behaved with deliberate casualness. In June, he went to London, then on to Trouville and Biarritz.

In Biarritz, Bismarck met Princess Katherine Orlov, the young wife of the elderly Russian Ambassador to Belgium. Detached from Johanna, who was in Pomerania with the children, Bismarck fell in love. Katherine Orlov was twenty-two, Bismarck forty-seven; they walked in the mountains together, picnicked, and bathed in the Atlantic surf; she played Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Schubert while he listened, entranced. The intense relationship remained publicly acceptable: she called him “Uncle” and her husband did not appear to object. Bismarck wrote straightforwardly to Johanna. Describing a picnic, he said, “Hidden in a steep ravine15 cut back from the cliffs, I gaze out between two rocks on which the heather blooms at the sea, green and white in the sunshine and spray. At my side is the most charming woman, whom you will love very much when you get to know her... amusing, intelligent, kind, pretty, and young.” Johanna’s reaction, writing to a friend, was, “Were I at all inclined16 to jealousy and envy, I should be tyrannized to the depths now by these passions. But my soul has no room for them and I rejoice quite enormously that my beloved husband has found this charming woman. But for her he would never have found peace for so long in one place or become so well as he boasts of being in every letter.” When the Orlovs left Biarritz, Bismarck accompanied them, as, twenty-five years before, he had followed Isabella Lorraine-Smith. The threesome went to Toulouse, then to Avignon. But the Orlovs were going to Geneva; Bismarck had been summoned to Berlin. On September 14, he said good-bye to Katherine. She gave him an onyx medallion, which he carried on his watch chain until he died.

In Berlin, the King and his parliament remained deadlocked. Twice, the assembly had been dissolved; twice, new elections had returned an even larger number of liberals determined to insist on a two-year term of service. William was adamant: he was Commander-in-Chief of the army; if he could not dictate the terms of military service, then being King was meaningless and he was prepared to abdicate. Only the refusal of his son Frederick to succeed him had prevented him from doing so already. Roon, in extremis, waited no longer. He wired Bismarck in Paris: “PERICULUM IN MORA!17 DÉPÊHEZ-VOUS!” (“Delay is dangerous! Hurry!”)

On September 20, Bismarck, unbeknownst to the King, arrived in Berlin. When William that day admitted to Roon that only Bismarck could carry out the kind of unconstitutional action they were discussing, he added, reassuring himself, “But, of course, he is not here.” Roon pounced: “He is here18 and is ready to serve Your Majesty.” The climactic meeting between William I and Bismarck took place on September 22 in the summer palace of Babelsberg on the Havel River. The two men went for a walk in the park. William said that he could not reign with dignity if parliament overruled his royal prerogative on matters affecting the army. Bismarck replied that, given supreme power in domestic and foreign affairs, he would form a ministry and put through the King’s demands regarding the army, with or without the consent of parliament. All he would need was the support of the monarch. Bismarck emerged from the audience as Acting Minister-President and Foreign Minister–Designate of the Prussian kingdom. Eight days later, he inaugurated twenty-eight years of rule with a famous speech which stated his philosophy and supplied a phrase which, more than any other, is identified with Bismarck. Explaining to the Budget Committee of the Landtag why, in the Prussian monarchy, the King must be allowed to make decisions about the army, he said, “Germany does not look19 to Prussia’s liberalism but to her strength.... The great questions of the day will not be decided by speeches and the resolutions of majorities—that was the great mistake of 1848—but by iron and blood.”fn1

The deputies voted 251 to 36 against the army plan and Bismarck sent them home. When they returned on January 27, 1863, he gave them a lecture on the relationship of the crown to a representative assembly in Prussia. If the assembly refused to vote necessary funds, the crown was entitled to carry on the government and collect taxes under previous laws. He, the King’s Chief Minister, had not been appointed by and could not be dismissed by Parliament. “The Prussian monarchy20 has not yet completed its mission,” he said. “It is not yet ready to become a mere ornamental decoration of your constitutional edifice.” To Motley, he expressed his contempt for the deputies: “Here in the Landtag21 while I am writing to you, I have to listen... to uncommonly foolish speeches delivered by uncommonly childish and excited politicians.... These chatter-boxes cannot really rule Prussia... they are fairly clever in a way, have a smattering of knowledge, are typical products of German university education; they know as little about politics as we knew in our student days.”

It did not matter to Bismarck whether Prussian conscripts served two years or three in the army, but it mattered to the King and Bismarck needed the King. Bismarck cared about a free hand in foreign policy. His objective was to make Prussia, not Austria, predominant in Germany. Events soon played into his hands. The twin duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, northwest of Berlin at the base of the Jutland peninsula, had been ruled by the King of Denmark for four hundred years. The populations were mixed: Holstein, which reached to the outskirts of Hamburg, was mostly German; Schleswig, on the eastern side of the peninsula and containing the magnificent fjord and port of Kiel, was mostly Danish. In 1848, as the high tide of nationalism rolled across Europe, the German Holsteiners rose against the Danes. Prussia, with the approval of the Frankfurt Diet, sent troops to aid the Holsteiners. Conservative Europe, including Russia and Great Britain, rallied to Denmark and demanded that the Prussians withdraw. An international agreement, the 1852 Treaty of London, guaranteed the status quo: the two duchies would remain attached to the Danish Crown, but the King of Denmark would make no attempt to absorb them into his kingdom. In March 1863, six months after Bismarck became Minister-President of Prussia, the new King Christian IX of Denmark breached the Treaty of London by proclaiming the two duchies an integral part of Denmark. The Holsteiners refused to swear allegiance and again appealed to the Diet at Frankfurt.

Bismarck, for his own reasons, was pleased by the crisis. He had no interest in Holsteiner nationalism. “Whether the Germans in Holstein22 are happy is no concern of ours,” he remarked. His interest was in the extension of Prussian power. While the majority of Germans in Schleswig, Holstein, and throughout Germany wanted only the restored independence of the duchies under a prince of then-own choosing, Bismarck from the outset was bent on saving the duchies from Denmark in order to annex them to Prussia.

Austria was forced to support Prussia. Nominally, she was the first power in Germany and all Germany was demanding support for the duchies. To do nothing would mean abandoning leadership to Prussia. In January 1864, Prussia and Austria formed an alliance to enforce the Treaty of London. On January 16, Bismarck gave King Christian an ultimatum to evacuate Schleswig within twenty-four hours. The Danes refused. Holstein was occupied without resistance. A combined Austro-Prussian army advanced into Schleswig, resisted by forty thousand Danes. Great Britain, tending toward sympathy with Denmark, was stymied by Denmark’s incontrovertible breach of the Treaty of London; the British government restricted itself to insisting that the Austro-Prussian advance halt at the frontier of Denmark proper. On July 8, Denmark capitulated, formed a new cabinet, asked for peace, and surrendered the duchies.

At the end of August, Bismarck accompanied King William I to Vienna to discuss the future of the duchies with Emperor Franz Josef and his ministers. The Austrian response was vague, but Bismarck encountered immediate opposition from his own King. William I knew that he possessed no title, legal or historical, to the two duchies. He categorically refused to seize and annex them. No agreement was reached and both duchies remained under temporarily joint Austro-Prussian condominium. A year later, in August 1865, Holstein was assigned exclusively to Austria, Schleswig to Prussia. As evidence that Berlin considered Schleswig now permanently Prussian, the infant Prussian Navy began construction of its principal naval base at Kiel.

Victory over Denmark, for which William I promoted Bismarck to the rank of Count, was the Minister-President’s first external triumph. He had “liberated” Schleswig and Holstein, entangled Austria in a corner of Germany far from home, and laid the basis for a confrontation he felt certain of winning. Over the winter and spring of 1866, Bismarck repeatedly provoked Austria. He demanded that the German Confederation be reformed by a new national German parliament, which would create a new German constitution from which Austria would be excluded. When Austria refused to abandon her primacy and give Prussia a free hand to organize a new federal system, Bismarck signed an alliance with Italy against Austria and let Vienna know that war was imminent. In May, he announced that Prussia had as much right to Holstein as to Schleswig. On June 6, he ordered Prussian troops to enter Holstein. On June 15, Prussia delivered ultimatums to neighboring Hanover and Saxony: Prussian troops would march through their territories to attack Austria; resistance would mean war with them also.

When war between Prussia and Austria began, Europe predicted overwhelming defeat for Prussia. The Hapsburg Empire had a population of 35 million; Prussia, 19 million. The German kingdoms of Hanover, Saxony, Bavaria, and Württemberg, and the grand duchies of Baden and Hesse—with combined populations of 14 million—sided with Austria. On June 23, General Helmuth von Moltke’s three Prussian armies totalling 300,000 men marched swiftly into Bohemia. King William I was with the army, and Major Otto von Bismarck, costumed in a spiked helmet and cavalry boots, rode beside the King. At Königgrätz (or Sadowa, as it was called in France and England), the Austrians stood. Five hundred thousand men and fifteen hundred guns on both sides fought throughout the day, with heavy losses on both sides. At three-thirty in the afternoon, the Austrians appeared to be winning when Crown Prince Frederick with a fresh army of eighty thousand Prussians appeared on the Austrian flank. By evening the Austrian Army was in disorderly retreat toward Vienna. In a single day, Austria’s position in Germany had been destroyed.

The question, in the days immediately following the battle, was what Prussia was to make of its victory. Moltke wished to pursue and destroy the retreating Austrian Army. King William, who had gone to war reluctantly and only after Bismarck had convinced him that Austria was about to attack, was now flushed with moral rectitude and military glory; wicked Austria must be punished by surrendering territory and submitting to a triumphal march of the victorious Prussian Army through Vienna. Bismarck was adamant: a total Austrian withdrawal from Germany was sufficient; in the years ahead, he would need Austrian support in his confrontation with France. Prussia would not be made stronger by annexing Austrian territory, he told the King. “Austria was no more wrong23 in opposing our claims than we were in making them,” he said. To Johanna, he wrote that he had “the thankless task24 of pouring water into their [the King’s and the generals’] sparkling champagne, and trying to make it plain that we are not alone in Europe but have to live with three other powers [Austria, France, and Russia] who hate and envy us.”

For a while, it seemed that Bismarck and moderation would lose and that Moltke would march into Vienna and dismember the Hapsburg Empire. In a castle in Nikolsburg, where Austrian representatives were coming to sign an armistice, Bismarck decided that the King would favor Moltke. In despair, he withdrew from the King and climbed the stairs to his fourth-floor room; later, he said that he had considered throwing himself out the window onto the courtyard below. But as he sat, head in hands, he felt a hand on his shoulder. It was the Crown Prince. “You know that I was against this war,”25 said Frederick. “You considered it necessary and the responsibility for it lies with you. If you now think that our end is attained and that it is time to make peace, I am ready to support you and defend your view against my father.” He went down the stairs and later returned. “It has been a very difficult business but my father has consented,” he said.

The Treaty of Prague, signed on August 23, redrew the map of Germany. Austria surrendered no territory but withdrew all claim of influence in Germany. The Diet at Frankfurt was dissolved. A new political entity, the North German Confederation, dominated by Prussia, was created north of the river Main. Schleswig and Holstein were annexed by Prussia. Those German states which had sided with Austria against Prussia suffered harshly. Hanover, most of Hesse, and the free city of Frankfurt were annexed, and the King of Hanover was dethroned. The King of Saxony kept his crown, but his kingdom was incorporated into the North German Confederation. The four states south of the Main—Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, and Hesse-Darmstadt—retained their independence but were required to pay heavy war indemnities. Bismarck also insisted that they sign secret treaties of military alliance with Prussia, which included agreements to put their armies under Prussian command in wartime.

The reverberations of Prussia’s victory rolled across the Continent. By showing itself the military superior of Austria, Prussia threatened France’s position as the dominant power in Europe; French hegemony had been based in part on antagonism between Austria and Prussia. Adolphe Thiers, a French statesman, understood what had happened. “It is France which has been beaten at Sadowa,”26 he said. Napoleon III, too late, decided to intervene and proposed calling a congress which would roll back some of Prussia’s gains. Bismarck quickly showed his teeth. “If you want war,27 you can have it,” he told the French Ambassador. “We shall raise all Germany against you. We shall make immediate peace with Austria, at any price, and then, together with Austria, we shall fall on you with 800,000 men. We are armed and you are not.”

Bismarck’s preoccupation for the four years that followed was France. The Empire of Napoleon III based its foreign policy on two assumptions: France was the greatest power in Europe, and its supremacy must not be challenged by a unified Germany. The North German Confederation, the result of Prussia’s sudden, startling victory over Austria, was as far as France would permit Bismarck to go; any movement toward greater unification would lead to a Franco-Prussian war. Bismarck knew this and was determined to profit. To promote German unity, the Minister-President of Prussia, now also Federal Chancellor of the North German Confederation, required an enemy against whom all Germans could be rallied. France—Bourbon or Bonapartist—which had been the strongest military power in Europe for more than two centuries, was the only plausible antagonist.

The pretext, when it came, did not originate with Bismarck. The government of Spain, having deposed a dissolute Bourbon, was seeking a new monarch. In September 1869, the Spanish crown was secretly offered to Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern, a distant cousin of King William I. The family relationship entitled William to approve or disapprove acceptance by a Hohenzollern of a foreign crown. William, interested only in Prussia, was not inclined to approve. Accordingly, Prince Leopold, a Roman Catholic then serving as an officer in the Prussian army, declined, citing the confused state of affairs in Spain. The Spaniards asked again. This time, Bismarck, who favored acceptance, badgered and bullied the King until William “with a heavy, very heavy, heart”28 agreed. No one—neither Spaniards nor Prussians—said anything to the French; it was understood that France, not wishing to be surrounded by Hohenzollerns in the event of war, would bitterly oppose Prince Leopold’s candidacy.

When the French government and public first heard the news on July 3, 1870, there was an outburst of alarm and denunciation. “The honor and interests of France29 are now in peril,” declared the Due de Gramont, Napoleon III’s Foreign Minister. “We will not tolerate a foreign power placing one of its princes on the [Spanish] throne and thus disturbing the balance of power.” King William of Prussia, anxious to ameliorate the crisis, again encouraged Prince Leopold to renounce the Spanish crown, which Leopold was happy to do. Bismarck, his policy in apparent ruins, threatened to resign. And then, Gramont and France, having achieved a public diplomatic triumph, went too far. Gramont sent the French Ambassador to visit King William I, who was vacationing at the spa of Ems. France insisted, William was told, that the King of Prussia not only give his formal endorsement to the renunciation, but “an assurance that he will never30 authorize a renewal of the candidacy.” William read this demand, coolly refused, and walked away from the Ambassador. Then he telegraphed Bismarck to tell him what had happened. Bismarck changed the wording of the telegram slightly, editing out moderating sentences and phrases, so as to make the King of Prussia’s words seem more insulting to France. He gave the edited telegram to the press. The following day, Parisian newspapers demanded war and Parisian crowds shouted “À Berlin!” Germany rallied to Prussia, the armies were mobilized, and four days later, war was declared.

This time, Europe promised itself, Prussia was finished. The French Army possessed the reputation of the finest fighting machine in the world. Marshal Edmond Leboeuf had assured the Emperor Napoleon that his army was ready “to the last gaiter button.”31 Moltke immediately began a carefully planned invasion of France by four hundred thousand troops—Bavarians, Württembergers, Hessians, Saxons, and Hanoverians, as well as Prussians. King William I, seventy-four, was in nominal command; at his side was Major General Otto von Bismarck, again in a blue Prussian uniform. This phase of the war lasted only a month. On September I, Napoleon III personally surrendered at Sedan with an army of 104,000; on September 4, the Empress Eugénie fled Paris for a life of exile in England; on September 5, France proclaimed a republic. Bismarck recommended that the German Army halt and draw up a defensive line at its present positions in eastern France. This time Moltke and the King prevailed; the army marched on Paris, ringed the city with artillery, and, after a delay for early peace negotiations, began a bombardment which would last four months.

Once again, Bismarck confronted the generals. He wanted, as with Austria, a quick victory, followed by reconciliation. His objective was political, not military: establishment of a unified Germany by transforming the simple military alliances that bound South Germany to Prussia into a real political entity. Moltke’s concerns were purely military: he wanted enough French territory to create a buffer for Germany from future attacks from the west; he asked for the city of Strasbourg, the fortress of Metz, and the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. Bismarck was willing to compromise: Strasbourg and Alsace had been German two centuries before until wrenched away by Louis XIV. He was not eager to acquire Metz and Lorraine, both predominantly French in language and culture. “I don’t like so many Frenchmen32 in our house who do not want to be there,” he said. This time, the King ruled in favor of Moltke and both provinces were annexed to victorious Germany. This decision changed the international perception of the war; France had at first been seen to have begun it, but now the war seemed to be one of German aggression and conquest. “We are no longer looked upon33 as the innocent victims of wrong, but rather as arrogant victors,” worried Crown Prince Frederick. Europe would see Germany, “this nation of thinkers and philosophers, poets and artists, idealists and enthusiasts... as a nation of conquerers and destroyers.”

During the bombardment of Paris, German Army headquarters was established in Versailles. Because the King and Bismarck remained at headquarters, the governments of Prussia and the North German Confederation, the Prussian Court, and the courts of twenty German princes all crowded into the palace and town built by Louis XIV. Bismarck announced that his goal was the creation of a new German empire, built around Prussia, with the King of Prussia proclaimed the new emperor. The princes of the German states already in Versailles agreed. The obstacle was King William. The King regarded his hereditary title of King of Prussia as superior to the new imperial title Bismarck was about to give him; he disliked the South German states and worried about a dilution of the stern, military qualities which had brought Prussia to this summit. If he were to accept a new title, he wished it to be a significant one: “Emperor of Germany” or “Emperor of the Germans.” Bismarck, knowing that the South Germans would not accept any such sweeping title, offered only “German Emperor,” a glorified presidency of the empire. The dénouement came in a dramatic scene in the Hall of Mirrors on January 18, 1871, while the roar of guns bombarding Paris rattled the windows. William, hoping to foil Bismarck at the ceremony, asked the Grand Duke of Baden to raise a cheer for “the Emperor of Germany.” Bismarck intercepted the Grand Duke on the stairway and persuaded him to compromise with “the Emperor William.” When the cheer rang out, the newly proclaimed Emperor was so indignant that, stepping down from the dais to shake hands with his princes and generals, he walked past Bismarck, refusing to look at him and ignoring his outstretched hand.

On January 28, Paris capitulated, an armistice followed, and a treaty was signed. Strasbourg, Metz, Alsace, and Lorraine were stripped away and a war indemnity of 5 billion marks imposed. On March 6, Bismarck left Versailles, never to see France again; indeed, never thereafter to leave Germany. On March 21, the new Emperor William raised Count von Bismarck to the rank of Prince and granted him the estate of Friedrichsruh near Hamburg. Bismarck also received the Grand Cross of the Hohenzollern Order set in diamonds. “I’d sooner have had a horse34 or a good barrel of Rhenish wine,” he said.

On June 16, 1871, under a cloudless sky, Bismarck, Moltke, and Roon, riding abreast, led a victory parade through Berlin. Alone, behind this trio, rode their new Imperial master, Kaiser William I, followed by a squadron of German princes, eighty-one captured French regimental eagles and flags, and forty-two thousand marching German soldiers. The crowds, massed along the boulevards, thronging around the triumphal arches, cheered and waved and cried. German unity, a dream since the Middle Ages, had been achieved in a glorious new empire which was now the most formidable military power in Europe. In the days that followed, there were notes of apprehension: victory had been achieved not, as the liberals wished, by the German people acting through representative assemblies, or even by the free will of the German princes, but by Prussian military might, which had conquered Germany as well as Denmark, Austria, and France. Some knew that it was not the wish of the King of Prussia that this unity be achieved and the Empire created. All Germans understood that the creation, structure, and future direction of the new Imperial state had been and were to be the work of one man: Otto von Bismarck.

For the moment, apprehensions were put aside; all was glory. Bismarck, at the pinnacle of his career, was the hero of Germany and the arbiter of Europe. His presence, his actions, his language, were said to be “haloed by the iron radiance35 of a million bayonets.” “His words inspire respect,36 his silences apprehension,” said Lord Ampthill, the British Ambassador.

The structure of the new empire represented Bismarck’s solution to the problem of governing Germany. It was neither pure autocracy nor constitutional monarchy, although it had elements of both. The new Reich was a federal system like the United States; in creating the 1866 constitution of the North German Confederation, the precursor of the Imperial constitution, Bismarck had studied the American Constitution. As the American union had been created by sovereign states at the end of the eighteenth century, so the German Empire was nominally created by sovereign princely states. The differences, of course, were more significant than the similiarities. The American states had chosen voluntarily to unite and had worked out the structure of their new government in convention and prolonged debate; the German states were herded into union by the Prussian army and handed a constitution written by Bismarck. No single state in the new American union possessed the overwhelming dominance of Prussia. Prussia contributed two thirds of the land area, two thirds of the population, and practically all of the industry of the German Empire. Eighteen of Germany’s twenty-one army corps were Prussian. Not only was it natural that Berlin should become the capital of the new empire and that the Minister-President of Prussia should be the new Imperial Chancellor; any other arrangement would have been unthinkable.

Bismarck’s constitution created three separate branches of government: the Presidency (always to be held by the King of Prussia as German Emperor), the Federal Council (Bundesrat), and the parliament (Reichstag). The Bundesrat was Bismarck’s gesture to federalism and the German princes. Nominally, the Empire still consisted of twenty-five princely states, each ruled by its own government; under the Empire, some of the German states still exchanged ambassadors with each other and even with foreign powers. Constitutionally, citizens of these states owed no allegiance to Emperor William I. “The Emperor is not my monarch,”37 said a politician from Württemberg. “He is only the commanding officer of my federation. My monarch is in Stuttgart.” The princes were subordinate, not to the Emperor, but to the Empire through the Bundesrat. Each German state sent a delegation to this body; each delegation was required to vote as a bloc. Of the Bundesrat’s fifty-eight members, seventeen were from Prussia, six from Bavaria, four each from Saxony and Württemberg. As no change could be made to the constitution if fourteen delegates were opposed, the seventeen Prussian delegates, always voting en bloc, could make sure that the imperial constitution remained unaltered.

The Reichstag, the democratic branch of the Imperial government, was elected by universal male suffrage and secret ballot, an evolution of democracy which no other European state, not even England, had yet attained. In Germany, the appearance was grossly misleading; the German Social Democrat Wilhelm Liebknecht scorned the Reichstag as “the fig leaf of absolutism.”38 Although the Reichstag voted on the federal budget and its consent was necessary for all legislation, the restrictions placed on it were crippling: it could not initiate legislation; it had no say in the appointment or dismissal of the Chancellor or Imperial Ministers, and the Emperor (or, in practice, the Chancellor) could with the agreement of the Bundesrat dissolve the Reichstag at any time.

The position of the monarch who presided over this government was constitutionally peculiar. The German Emperor was not a sovereign with ancient prerogatives; he had only the powers granted him by the constitution. Article XI of the Imperial constitution stated: “The presidency of the union belongs to the King of Prussia who in this capacity shall be titled German Emperor.” Nevertheless, the Kaiser possessed several critically important powers: he had personal control of the armed forces and made all appointments and promotions in the army and the navy. And he appointed (or could dismiss) all imperial ministers including the Imperial Chancellor.

More unusual still was the office of Imperial Chancellor, which Bismarck carefully crafted for himself. The Chancellor was appointed by the Emperor, entirely independent of the Bundesrat and the Reichstag. His tenure of office depended wholly on the will—or the whim—of the Emperor. Responsibility for foreign policy and war and peace were split; the Chancellor, not the Kaiser, had responsibility for German foreign policy, but the armed forces reported directly to the Kaiser and orders to the army and navy, including orders to begin a war, were exempt from requirement of the Chancellor’s countersignature. The senior members of the imperial bureaucracy (the State Secretaries of Foreign Affairs, the Treasury, the Navy, Interior, and Education) were subordinates of the Chancellor, appointed and dismissed by him with the Kaiser’s consent. They were not a Cabinet, either in the British or American sense; there was no collective responsibility as in England; there were no regular, joint meetings as in the United States. The overwhelming flaw in the constitution of the German Empire was that it was designed too closely to meet the needs and accommodate the talents of specific personalities. Fitted smoothly to the qualities of Bismarck and William I, it made the Chancellor the most powerful man in the empire. But, constitutionally, the Chancellor required the absolute support of the Kaiser. In other times, with other men—a restless, ambitious Kaiser, a weak, uncertain Chancellor—the Chancellor’s position was certain to be fatally undermined.

Politically, it was Bismarck’s extraordinary good fortune that William I remained on the throne as long as he did. Prince William of Hohenzollern was sixty-five in 1862 when he became King of Prussia, and seventy-four in 1871 when he assumed the imperial title; neither he nor Bismarck imagined that he would continue as Emperor for another seventeen years. During this span, Bismarck ruled the Empire and dominated Europe with no public sign of disapproval from the Emperor. In private, there were moments when the sovereign rebelled and threatened to step out from behind his role as figurehead; Bismarck usually dealt with these disturbances by threatening to resign. In fact, the Chancellor, venerating William in public, privately found the Kaiser dry and simplistic, and his insistence on faithfully executing his duty annoying. Der Alte Herr (the Old Gentleman), as Bismarck referred to him, demanded to be kept fully informed and then wished to discuss and approve all of the Chancellor’s actions. William insisted on seeing all diplomatic dispatches, then writing his comments and questions, which, to Bismarck’s chagrin, demanded answers. As much as possible, Bismarck withheld information from the monarch, not because he was not certain of overcoming William’s hesitations, but simply because he did not wish to take the time to do so.

The two men irritated each other even in little ways. Bismarck, plagued by insomnia, would arrive at the Castle eager to describe his sleepless night. The Kaiser would open their conversation by innocently saying that he had slept badly. William disliked the confrontations to which Bismarck often exposed him; often, when the Chancellor asked for an audience, he would send word that he was too exhausted. One day, out for a walk, the Kaiser saw Bismarck approaching. “Can’t we get into a side street?”39 William said to his companion. “Here’s Bismarck coming and I’m afraid that he’s so upset today that he will cut me.” There were no side streets; Bismarck came up, and fifteen steps away took off his hat and said, “Has Your Majesty any commands for me today?” William dutifully replied, “No, my dear Bismarck, but it would be a very great pleasure if you would take me to your favorite bench by the river.” The two, neither desiring to be with the other, went off to sit side by side. Bismarck expressed his sense of this burden by saying, “I took office40 with a great fund of royalist sentiments and veneration for the King; to my sorrow I find this fund more and more depleted.” The Kaiser said simply, “It is not easy to be emperor41 under such a chancellor.”

The years after 1871 seemed anticlimactic. The moments of daring calculation, of dramatic victories snatched from probable catastrophe, were over. “I am bored,”42 Bismarck said in 1874. “The great things are done.” He had no design in domestic politics beyond survival. In time, the national glow of triumph in unity wore off and each of the parties which made up the Reich grumbled that its interests were neglected. The wars had been won by the Prussian Army, the military embodiment of the Prussian Junker aristocracy, and the agrarian Junkers continued to demand predominance in the government of the empire. German liberals, the German middle class, and Germany’s new industrialists often opposed the Junker elite, and the Reichstag became a field of open warfare. The rapid expansion of German industry also gave rise to a new industrial proletariat, whose ambitions and goals clashed with those of both the Junkers and the prosperous middle class. Bismarck had somehow to balance these factions to get legislation through the Reichstag.

Bismarck’s decisions came after long periods of solitary brooding, not after lively discussions with others. Bismarck never exchanged ideas; he gave orders. Outside the Reichstag, he was rarely challenged. Yet neither mastery, success, nor fame calmed his loneliness or restlessness. Wherever he was, he felt out of place. “I have the unfortunate nature43 that everywhere I could be seems desirable to me,” he said, “and then dreary and boring as soon as I am there.” Bismarck acknowledged that his personality was complicated: “Faust complains44 of having two souls in his breast,” the Chancellor said. “I have a whole squabbling crowd. It goes on as in a republic.” Asked whether he really felt like the “Iron Chancellor,” he replied: “Far from it, I am all nerves.”45 He admitted his unruly temper: “You see,” he said, “I am sometimes spoiling for a fight46 and if I have nothing else at hand at that precise moment, I pick a quarrel with a tree and have it cut down.” He was lavish with insults; when a subordinate, Baron Patow, had proved inept, another subordinate in Bismarck’s presence called Patow an ox. “That seems to me rudeness47 to animals,” Bismarck said. “I am certain that when oxen wish to insult each other, they call each other ‘Patow.’” He made few friends. “Oh, he never keeps his friends for long,”48 Johanna sadly told Holstein. “He soon gets tired of them.” In his diary, Holstein noted: “Part of the trouble49 was Prince Bismarck’s habit of doing all the talking himself.... He always monopolized the conversation. He therefore preferred people who had not yet heard his stories.”

In Berlin, Bismarck could be found either at the Reichstag, at his office, or at home. He had no interest in society, never attended dinners, balls, weddings, or funerals, and entertained the diplomatic corps only once a year. Purporting to disdain the Reichstag, the Chancellor actually spent many hours there when it was in session. He entered through a private door, took his place on the dais, and began turning through and signing government papers as if he were in his office or his study at home. If personally attacked by a deputy, he stopped writing and began stroking his mustache. When the speaker finished, Bismarck immediately rose to reply, without asking permission from the Chair. He spoke in his high, thin voice, meditating aloud, wrestling for words, shifting from one leg to the other, pulling his mustache, studying his fingernails, spinning a pencil between his fingers, breaking off to drink a glass of brandy and water, sometimes remaining silent for several minutes. The deputies, losing interest, would begin to talk and laugh among themselves. Then Bismarck would shake his fist and shout at them, “I am no orator.50 I am a statesman.”

Bismarck’s office and home were on the Wilhelmstrasse, a fashionable and busy street extending north from Unter den Linden and containing a number of old palaces and stately mansions which had been converted into ministries. The Imperial Chancellory at No. 76 was an unimpressive two-story stucco building with a steep, red-tiled roof. Its authority was inauspicious: the paint was peeling; the door was guarded, not by a soldier or a policeman, but by an unliveried porter with neither a staff nor a badge of office. Bismarck’s office, a corner room on the ground floor to the left of the entrance, possessed two windows, an enormous mahogany desk, a carved armchair, and a massive leather couch on which the Chancellor liked to recline while reading official papers. The office displayed collections of meerschaum pipes, swords, buckskin gloves, and military caps, but no books. A bell sash hanging over the desk was used for summoning clerks, and a hole in the wall connected with an adjoining room which contained a telegraph to keep the Prince informed of what was happening in the Reichstag. Every ten minutes, while the Reichstag was in session, a length of tape was pushed through the aperture in the wall. Bismarck took it, read it, and threw it aside. While the Chancellor worked, his giant dog, Tiras, lay on the carpet, staring fixedly at his master. Tiras, known as the Reichshund (dog of the empire), terrorized the Chancellory staff, and people speaking to Bismarck were advised to make no unusual gestures which Tiras might interpret as threatening. Prince Alexander Gorchakov, the elderly Russian Foreign Minister, once raised an arm to make a point and found himself pinned to the floor, staring up at Tiras’ bared teeth.

Until 1878, the Chancellory building at No. 76 Wilhelmstrasse had also been the Chancellor’s home. In that year, as the Congress of Berlin was about to convene, the Imperial government, concerned about foreign opinion, purchased a separate residence for the Chancellor. The Radziwill Palace, next door to No. 76, was an elegant eighteenth-century building occupying three sides of a paved courtyard. Here, surrounded by his family, Bismarck was able to relax. Dinner was served at five; supper at nine. When the Chancellor was finished, the meal was over. He signalled this by rising from his chair and taking a seat at a small table in the parlor. Here, he filled his porcelain pipe and waited for coffee. He told stories, described what had happened in the Reichstag, joked with his grandchildren, and made the women laugh.

On the rare occasions when Bismarck entertained, guests were astonished by the lavish table spread by the Princess and the courtesy and warmth exhibited by the Prince. Visitors arriving at ten P.M. would find awaiting them Brunswick sausages, Westphalian ham, Elbe eels, sardines, anchovies, smoked herrings, caviar (usually a gift from St. Petersburg), salmon, hard-boiled eggs, cheeses, and bottles of dark Bavarian beer. Bismarck appeared at eleven. “I never saw Bismarck enter51 the room without the feeling that I saw a great man, a really great man, before me, the greatest man I ever saw or ever would see,” said Bernhard von Bülow, the future Chancellor. Every male guest was greeted with a handshake; every woman with a slight bow and a kiss on the hand. In later years, when he was forced by gout to recline on a sofa, he asked forgiveness from the women for receiving them in this position. Bismarck always dominated the conversation, sometimes speaking so softly that his guests had to strain to catch his words. When he was silent, the company was silent, afraid of disturbing his thoughts or being caught speaking when he began to speak again.

When the Chancellor was not in Berlin, he was at one of his immense country estates, Varzin or Friedrichsruh. Varzin, in Pomerania, spread over fifteen thousand acres and containing seven villages, was purchased with a grant of money voted by the Prussian Landtag after Königgrätz. It was remote—five hours by train from Berlin, followed by forty miles on bad roads. Johanna thought the house “unbearably ugly”;52 Bismarck found it ideal. The forest was filled with giant oaks, beeches, and pines; there were deer, wild boar—and few neighbors. In 1871, after the proclamation of the empire, William I rewarded the new Prince Bismarck with Friedrichsruh, an even larger estate of seventeen thousand acres near Hamburg. It had the same stately forest, rich stocks of game, and sense of isolation. Bismarck could roam all day, carrying his gun, or, increasingly, only a pair of field glasses. The house at Friedrichsruh, originally a hotel for weekenders from Hamburg, was even less pleasing to Johanna. Bismarck installed his family without bothering to remove the numbers from the bedroom doors, refused to bring in electricity, and permitted illumination only with oil lamps. Soon, the cellar was filled with thousands of books which he had been given but would never read. Bülow, a visitor, struggled to describe the primitive state of the Chancellor’s retreat: “Simplicity... complete lack of adornment53... not a single fine picture... not a trace of a library... The whole house seemed to reiterate the warning: ‘Wealth alone can destroy Sparta.’”

Bismarck complained constantly about his poor health but did nothing to improve it. He smoked fourteen cigars a day, drank beer in the afternoons, kept two large goblets—one for champagne, the other for port—at hand during meals, and tried to find sleep at night by drinking a bottle of champagne. Princess Bismarck believed that her husband’s well-being depended on appetite. “They eat here always until the walls burst,”54 reported a Chancellory assistant who visited Varzin. When the Prince complained of an upset stomach, Johanna calmed him with foie gras. When the pâté was brought to the table, the visitor reported, Bismarck first served himself a large portion, then followed the platter with his eyes around the table with such intensity that no one dared to take more than a small slice. When the platter came back to him, Bismarck helped himself to what remained. At night, he slept poorly or not at all. Often, he lay awake until seven A.M., then slept until two P.M. Lying in bed, he mulled over grievances. “I have spent the whole night hating,”55 he said once. When no immediate object of hatred was available, he ransacked his memory to dredge up wrongs done him years before.

He suffered and complained continually. “This pressure on my brain56 makes everything that lies behind my eyes seem like a glutinous mass,” he wrote to the Emperor in 1872. [I have] unbearable pressure on my stomach with unspeakable pains.” Between 1873 and 1883, he suffered from migraine, gout, hemorrhoids, neuralgia, rheumatism, gallstones, varicose veins, and constipation. His teeth tormented him, but he refused to see a dentist; eventually his cheek began to twitch with pain. He endured the twitching for five years and grew a beard to hide it. In 1882, when the teeth were drawn, the twitching stopped, but the pain in the cheek remained.

Bismarck’s appearance shocked those who saw him. His beard had come in white, his face and body were pink and bloated. His weight ballooned to 245 pounds. “The Chancellor has aged57 considerably over the last few months,” Holstein recorded in 1884. “His capacity for work is less, his energy has diminished, even his anger, though easily kindled, fades more quickly than in his prime.”

When the doctors announced to Johanna that her husband had cancer, she became sufficiently frightened to bring a new doctor, a young Berlin physician named Ernst Schweninger, to Friedrichsruh. Schweninger from the beginning confronted his patient head-on. At their first meeting, the Chancellor said roughly, “I don’t like questions.”58 “Then get a veterinarian,” Schweninger replied. “He doesn’t question his patients.” Bismarck immediately gave in. Schweninger became a member of the Bismarck household and dictated to the Chancellor as if he were a schoolboy. He prescribed an exclusive diet of fish, mainly herring, forced Bismarck to drink milk before bedtime instead of beer or champagne, and curtailed his drinking of alcohol at other times. Within six months, the Chancellor’s weight dropped to 197 pounds, his eyes became clear, his skin fresh, and he began to sleep peacefully at night. In 1884, he shaved off his beard. Schweninger left the household but returned often to monitor the Chancellor’s diet. This was necessary, Holstein reported, because Bismarck’s “inclination to transgress59 is reinforced by Princess Bismarck who is never happier than when watching her husband eating one thing on top of another.”

Bismarck’s affection for his three children, Marie, Herbert, and William (known all his life as Bill), was fierce, protective, and jealously possessive. At the height of the war with France, Bismarck, at army headquarters with the King, was told that Herbert had been killed and Bill wounded. He rode all night to find Herbert shot through the thigh but out of danger and Bill recovering from a concussion caused by a fall from a horse. Herbert, born in 1849, was his father’s favorite; no man was closer to Bismarck. As a boy, Herbert was handsome, quick-witted, and spoiled. As he grew older, the power and deference that surrounded his father and his family had a destructive effect on the impressionable son. Attempting to copy his father, Herbert exaggerated. Where Otto was lofty, self-confident, and ironic, Herbert became arrogant, flamboyant, and sarcastic.

Once Herbert entered the Foreign Ministry, the Chancellor ensured choice assignments and quick promotions, while ruthlessly crushing Herbert’s independence. Herbert had been in love for a long time with a married woman, Princess Elisabeth Carolath. In the spring of 1881, when Herbert was thirty-two, Elisabeth divorced her husband, expecting to marry Herbert. German newspapers speculated openly and uncritically about the marriage; unlike in Britain, where divorce was unthinkable, divorce was no handicap in Imperial Germany. But Herbert’s decision stimulated violent antagonism in his father. Elisabeth Carolath was closely related to an old enemy of the Chancellor’s. More important, Bismarck feared that the elegant and cosmopolitan Elisabeth would weaken Herbert’s devotion to him. Using every available weapon, Bismarck threatened to discharge Herbert from the Foreign Ministry if he married Elisabeth; he persuaded the Emperor to decree that Varzin and Friedrichsruh could not pass to anyone who married a divorced woman; he sobbed that he would kill himself if the marriage took place. Herbert, subjected to this intimidation, torn between love and filial obligation, threatened with disgrace, disinheritance, and poverty, floundered helplessly. Eventually, Elisabeth, contemptuous, called off the marriage.

Shattered and surly, Herbert smothered his frustrations in drink. Bülow recalled staying up with him all night in Parisian cafés while Herbert drank bottles of heavy Romanée-Conti or dry champagne; then Herbert would appear at lunch the next day and finish off a bottle of port. First Counselor Holstein, who knew the Bismarck family intimately, observed: “Herbert’s character is unevenly developed.60 He has outstanding qualities, first-rate intelligence and analytical ability. His defects are vanity, arrogance, and violence.... He is an efficient worker, but is too vehement. His communications with foreign governments are too apt to assume the form of an ultimatum. Bismarck is afraid of his son’s vehemence. During our disputes with England over colonial affairs, Herbert once wrote [Georg Herbert von] Münster [German Ambassador to England] a dispatch which was, in tone, simply an ultimatum. The Chancellor laid the document aside, remarking that it was a bit too early to adopt that tone.”

In 1885, Bismarck decided to catapult his son into one of the Reich’s senior offices, the State Secretaryship for Foreign Affairs. Count Paul von Hatzfeldt, who preceded Herbert, was charming but weak; Herbert was already fulfilling many of the functions of the office. “Even now, the ambassadors seek out Herbert61 rather than Hatzfeldt because the latter is cautious and the former is talkative and informative and tells more than is good for us,” Holstein wrote in his diary. “The way to loosen Herbert’s tongue62 is to invite him to a morning meal or lunch and serve exquisite wines.” On May 16, Holstein observed: “Both father and son63 are at present pursuing the aim of making the son State Secretary, not just yet, but as soon as possible.” On June 28, he wrote of the Chancellor’s “eagerness to get rid of Hatzfeldt.64... My guess is that Hatzfeldt will have to go because Bismarck is firmly resolved that the post of State Secretary will fall vacant, come what may.... What is aimed at is a reshuffle of ambassadors in which something reasonable will be found for Hatzfeldt.” In the autumn, the reshuffle took place. Hatzfeldt became ambassador to England. And Herbert, at thirty-six, replaced Hatzfeldt as State Secretary.

As State Secretary, Herbert’s role was enhanced by his possession of his father’s confidence; in time, he was regarded almost as the Chancellor’s alter ego. Despite family closeness, official relations between father and son remained formal: Herbert addressed his father in official correspondence as “Your Highness.” Nor did he presume that the Chancellor would forgive a lax performance. Planning to take one day away from his post in Berlin, he wrote to his brother-in-law at Varzin: “Please do not say anything65 about this.... Papa could find in it a dereliction of duty.” In 1886, when Herbert became seriously ill and the Chancellor was told that his son’s decline was due to the demands of office, Bismarck replied, “In every great state66 there must be people who overwork themselves.”

Again, Herbert found solace in drink. In the evenings, the State Secretary was usually in a state of alcoholic befuddlement; in the mornings he suffered from debilitating hangovers. In restaurants, he was peevish, barking orders at waiters. Within a few weeks of becoming State Secretary, he lurched into the courtyard of the Foreign Ministry carrying a small rifle and began shooting at the windows of officials. Invited to Paris by the French Ambassador, he sneered, “I never go to Paris67 except in war time.” When the Emperor Frederick was dying of throat cancer, Herbert told the Prince of Wales, the Emperor’s brother-in-law, that “an emperor who could not talk68 was not fit to reign.” The Prince said afterwards that if he had not valued good relations between Germany and England, he would have thrown Herbert out of the room.

Herbert’s promotion to a key post in the Imperial Government seemed to mark him as the Chancellor’s intended political heir. Herbert himself, having participated in many important decisions, felt his succession natural. At the same time, he knew the weakness of his position: whatever his talents, it would be said he had succeeded only because of his father. But it was the Kaiser who would appoint Bismarck’s successor. There would, at least, be no further advancement under Kaiser William I, who had only reluctantly approved the appointment of the Chancellor’s son as State Secretary. Subsequently, the old Kaiser regretted his decision: “These audiences with young Bismarck69 always take a lot out of me,” he said. “He’s so stormy—even worse than his father. He has not a grain of tact.” Near the end of his life, William I said to a military aide, “Lately, it almost appears70 that the Prince would like to see Herbert take his place one day. That is quite impossible. As long as I live, I will never part from the Prince who will most probably, and as I hope, survive me. He is eighteen years younger than I am. Nor will my successors wish to make the Chancellor’s office an hereditary one. That won’t do.” Bismarck, despite his hopes for Herbert’s future, had no illusions about his son: “Herbert, who is not yet forty,71 is more unteachable and conceited than I, and I am over seventy. I have had a few successes.” To an official who praised Herbert’s industry as State Secretary, Bismarck said, “You need not praise him72 to me. I would have made him State Secretary even if he had not possessed all those qualities for which you praise him, since I want at my side a man in whom I can have complete confidence and whom it is easy for me to deal with. At my great age, when I have used up all my energies in the royal service, I think I have the right to ask that.”

fn1 Subsequently, the phrase was reversed to the more sonorous “blood and iron.”