I would annex the planets1 if I could,” Cecil Rhodes had cried one night, staring up at the heavens. In 1895, the most dynamic figure on the African continent was at the peak of his career. He was Prime Minister of the Cape Colony of South Africa, he had added territories as large as Western Europe to the British Empire, and he was one of the richest men in the world. At forty-two, he was called “the Colossus.”2

Rhodes was born in 1853, the sixth of nine children of a stern Hertfordshire vicar and his wife. Cecil was his mother’s favorite among her seven sons; she called only him “my darling.”3 At seventeen, he left England to join his older brother Herbert, who was growing cotton in Natal. When diamonds were discovered at Kimberley on the northern edge of the Cape Colony, Rhodes and his brother rushed to stake claims. In 1873, Cecil, twenty—already earning £10,000 a year—returned to England to pay his own way through Oriel College, Oxford. For the next eight years, Rhodes oscillated between two lives, doing a term or two at college, then returning, his Greek lexicon in his kit, to dig on the veldt. At Oxford, Rhodes, tall and slim with wavy, light-auburn hair and pale-blue eyes, played polo and joined clubs catering to dandies. He paid his bills by selling the uncut diamonds which he carried in a little box in his waistcoat pocket. “On one occasion,”4 a fellow student recalled, “when he condescended to attend a lecture which proved uninteresting to him, he pulled out his box and showed the gems to his friends and then it was upset and the diamonds were scattered on the floor. The lecturer looked up, and asking what was the cause of the disturbance, received the reply, ‘It’s only Rhodes and his diamonds.’”

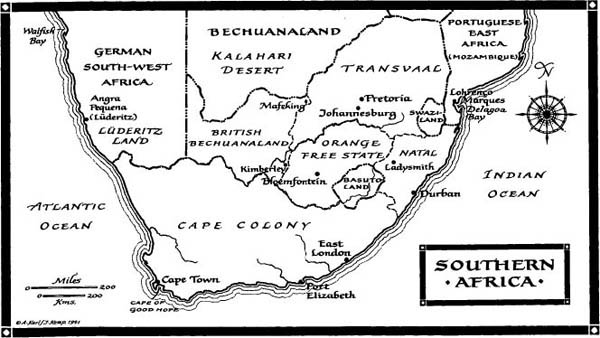

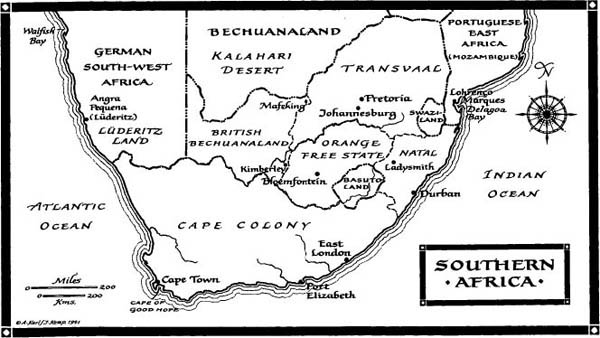

Rhodes’ diamonds had made him rich. By 1891, his De Beers Diamond Company controlled South Africa’s diamond production, which made up 90 percent of all the diamonds produced in the world. When gold had been discovered in 1886 in the Boer Republic of the Transvaal, Rhodes had become a leading investor in the Consolidated Gold Fields Company. Wealth had bought power. Rhodes had entered politics in 1878, and became an M.P. in the Cape Parliament ten months before he received his degree from Oxford. By 1890, at thirty-seven, he had become Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. It was not enough. Rhodes burned to extend the British Empire to the north, to bring southern Africa from Capetown to Lake Tanganyika into a single federated dominion of the British Crown. Britain’s “younger and more fiery sons,”5 he said, would thrust ahead and seize the land; the Crown would follow and annex. Bechuanaland, an area the size of Texas, was taken in this fashion; then the huge territory called Matabeleland, which Rhodes modestly named Rhodesia.fn1 “What have you been doing6 since I saw you last, Mr. Rhodes?” Queen Victoria asked in 1894. “I have added two provinces to your Majesty’s dominions,” Rhodes replied. That year, Lord Rosebery, the Prime Minister, made Rhodes a Privy Councilor.

Rhodes’ dreams extended beyond southern Africa. He wanted to build a railroad six thousand miles long up the eastern side of the African continent. He imagined the day when the Anglo-Saxons (to include Germans and Americans) would dominate a peaceful world in a permanent Pax Britannica. Rhodes once remarked, “If there be a God,7 I think that what He would like me to do is to paint as much of the map of Africa British as possible and to do what I can elsewhere to promote the unity and extend the influence of the English-speaking race.” What troubled Rhodes was that right in the middle of this glorious dream, spoiling it all, stood a little cluster of Dutch farmers, led by a rigid, Bible-quoting old man, who, it seemed, had a vision of his own.

The British were not the first Europeans to settle at the southern tip of the huge continent. In 1650, two and a half centuries before, the Dutch East India Company had begun a settlement at the Cape of Good Hope. In time, the settlers called themselves Afrikaners and spoke a variation of Dutch, Afrikaans. During the Napoleonic Wars, the British Navy quickly gobbled up the colony, but the majority of whites remained Afrikaners. In 1834, Parliament banned slavery throughout the British Empire. A fraction of the slave-owning Cape Afrikaners refused to accept this dispossession of their human property and set out to the north to escape the reach of English law. Through 1836 and 1837, five thousand Boers trekked north in covered wagons, taking along their cattle, sheep, and black slaves, fighting native tribes along the way. The Great Trek rumbled across the veldt for a thousand miles, and eventually came to a halt in a stretch of rolling hills beyond the Vaal and Orange Rivers. Here, the Boers climbed down from their wagons, hitched their oxen to the plow, and began to farm. Two small independent Boer states, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, were proclaimed and, in 1854, were recognized by the British government. In 1877, Britain, under Disraeli, reversed its decision and formally annexed the Transvaal. British troops entered Pretoria and raised the Union Jack. Three years later, the Boers revolted and, in February 1881, defeated a detachment of British troops at Majuba Hill. Gladstone, now in office and weary of Imperial adventures, compromised and offered the Boers internal self-government, a form of autonomy which left the republics’ foreign policy subject to British approval. This constitutional arrangement was embodied in the Convention of London, signed in 1881.

The most prominent Boer signature on the Convention was that of Paul Kruger, the President of the Transvaal Republic. Kruger’s life paralleled the history of his country. He had made the Great Trek as a boy of ten. He became a farmer and hunter; once, when an accident required the amputation of his thumb, Kruger took his hunting knife and performed the operation himself. He always carried his Bible; when he got off a train, people waiting to see him on the platform had to wait until he finished reading and closed the book. Kruger’s wide, pale face was fringed with whiskers and beard and he wore a top hat and frock coat. His eyes were small and black and he constantly spat. At seventy, he was the patriarch of the republic; his people knew him as Oom Paul (Uncle Paul).

Neither party to the London Convention had signed with enthusiasm. Kruger wrote his name on the document with great reluctance, making clear as time progressed that he would do his best to throw off the British yoke. Many Britons, especially officers of the army, considered the Boers and the Transvaal unfinished business. In their view, Gladstone had compromised too quickly, before the army had had a chance to vindicate its honor by reversing an early defeat.

Then, in 1886, huge reefs of gold ore, thirty miles long, 1,500 feet deep, were discovered in the Witwatersrand a few miles south of Johannesburg. Overnight, a city of tents sprang up, housing fifty thousand miners—Britons, Americans, Germans, and Scandinavians—the largest concentration of white men on the African continent. The city spread; tents became shacks, then barracks, then individual houses. Gigantic chimneys and mountains of slag arose beside the pit heads. The Rand was on its way to becoming the greatest source of gold in the world, exceeding the combined production of America, Russia, and Australia.

Gold produced social and political upheaval in the small republic of Bible-reading farmers. Foreign miners, called Uitlanders (outsiders) by the Boers, threatened to drown the state by sheer weight of money and numbers. Kruger and the members of the Executive Council—dressed like him in top hats, frock coats, brown boots—in their neat little capital of Pretoria with its careful streets lined with trees, shrubs, and flowers, were frightened by this rough mining-camp society. Uitlanders, Kruger believed, were godless, lawless, dirty, and violent; he characterized them publicly as “thieves and murderers.” To maintain Boer political control, Kruger established a five-year residency requirement for citizenship and voting; then he extended it to fourteen years. Discriminatory taxes were levied against miners; their children, if any, were taught in Boer schools in Afrikaans. The Times in London stated the Uitlander case and warned of danger:

“When a community8 of some 60,000 adult males of European and mainly English birth find themselves subjected to the rule of the privileged class numbering only a quarter of that figure and are refused the enjoyment of the elementary liberties now conceded to the subjects of the pettiest German principality, we know there can only be one ending to the matter. It is most desireable, however, that this development of constitutional freedom should take place in accordance with the peaceful precedents of English history.... It would be, we feel, a calamity to civilization in South Africa if the controversy had to be decided by an appeal to force.”

Talk of an armed uprising against the Boer government began to spread among the miners. Often, this talk involved the name of Cecil Rhodes. Rhodes wanted Paul Kruger and the Transvaal government removed from his path. They were a major obstacle to Rhodes’ imperial dreams: expansion of the Cape Colony to the north, a federation of South African states within the British Empire, a Cape-to-Cairo railway, the map of eastern Africa painted British red.

In the spring of 1895, Rhodes began to plot against the Transvaal government. Four thousand rifles, three machine guns, and over 200,000 rounds of ammunition were smuggled into Johannesburg under loads of coal or in oil tanks whose false bottoms had taps which would drip slightly if a customs official tried them. Four Uitlander leaders came to Cape Town, sat in wicker chairs on the Prime Minister’s veranda, and looked out at Table Mountain while they conspired against President Kruger. The uprising would begin with an attack by armed Uitlanders on the Boer arsenal at Pretoria. The attackers would come with carts to carry away the weapons they found inside so that, as they disarmed the Boers, they armed themselves. Rhodes did not ask the Uitlanders to rise without outside help. British troops could not be used, but Rhodes had a private army of men recruited into the service of the chartered British South Africa Company, of which Rhodes was chairman. Already this semimilitary force had enforced Rhodes’ will on Matabeleland. These men, Rhodes explained to the Uitlander leaders, would be stationed on the border of the Transvaal Republic; they would intervene if the uprising got into trouble. The commander of these troopers would be Rhodes’ best friend and principal lieutenant, Dr. Leander Starr Jameson.

“Doctor Jim,” as he was known in South Africa and later throughout the Empire, was an Elizabethan freebooter like Cecil Rhodes. A short, stocky, balding man, Jameson inspired comparison with loyal animals—which, from Englishmen, can be high recommendation. “The nostrils of a racehorse,”9 declared George Wyndham. His wide-apart, brown eyes reminded Lord Rosebery of “the eyes of an affectionate dog...10 there can scarcely be higher praise.” To one of his officers, Jameson’s look of eager anticipation was that of “a Scotch terrier11 ready to pounce.” A Scot, an eleventh and final child, trained as a surgeon, Jameson had come to Africa to practice in Kimberley, where his good nature and boyish grin quickly made him a favorite. He met Rhodes his first day in Kimberley and “we drew closely together,”12 Jameson said. Rhodes moved into Jameson’s one-story corrugated-iron bungalow, where the two lifelong bachelors shared two untidy bedrooms and a sitting room. “We walked and rode together,” Jameson continued, “shared our meals, exchanged our views on men and things, and discussed his big schemes.” “All the ideas are Rhodes’,”13 Jameson was to say and, at Rhodes’ bidding, “Doctor Jim” abandoned his scalpel and rode off to build an empire. At the head of Rhodes’ private army, Jameson had defeated King Lobengula of Matabeleland (and then had treated the captured King for gout).

In mid-October 1895, Jameson, on Rhodes’ instruction, began assembling men on the Transvaal’s western frontier about 170 miles from Johannesburg. He had 494 men, six machine guns, and three pieces of artillery. Three British army colonels, conveniently on extended leave from the Regular Army, were present to assist. His orders were to await word of the Uitlander rising, then, when summoned, to dash to Johannesburg across the veldt. Waiting, Jameson’s men grew bored and restless. The days stretched into weeks and still the Uitlanders in Johannesburg kept asking questions: Would the rising succeed? If it did, what would be the relationship of their new multinational polity to the Cape Colony? To the Empire? Jameson observed this procrastination with impatience and anger. Time was passing; soon, Kruger would uncover the entire conspiracy. “Anyone could take the Transvaal14 with half a dozen revolvers,” he declared. When the rising was fixed for December 28, and then postponed indefinitely, Jameson listened to the news and went outside his tent to pace. Twenty minutes later, he stepped back in and announced, “I’m going.”15 The following evening, in the bright moonlight of a midsummer night in the Southern Hemisphere, the troopers rode into the Transvaal.

It was a fiasco. After four days, Jameson’s men had ridden to within fourteen miles of the tall mine chimneys of Johannesburg. But they had been fighting all the way, they had not slept, and the deeper they penetrated into the Transvaal, the more Boers hurried out to bar the way. At eight o’clock on January 2, 1896, surrounded, outnumbered six to one, with seventeen dead, fifty-five wounded, and thirty-five missing, Jameson confronted the fact that his mission had failed. He raised a white flag. His men were disarmed and released immediately. Jameson himself and five officers, including the three British Regular officers, were handed over to the Cape government on the Natal border. From there, they were sent back to England for trial.

Five years later, when Great Britain attempted to subdue the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, it required three years and almost half a million soldiers.

In England, the public first heard about the Jameson Raid on the morning of New Year’s Day when it picked up its newspapers and read—in the Times for example—“CRISIS IN THE TRANSVAAL:16 APPEAL FROM UITLANDERS. DR. JAMESON CROSSES THE FRONTIER WITH 700 MEN.” Inside was the text of an appeal from five prominent Johannesburg Uitlanders asking Jameson to save them. “The position of thousands of Englishmen17 and others is rapidly becoming intolerable,” declared the letter, dated December 28. “Unarmed men, women and children of our race will be at the mercy of well-armed Boers, while property of enormous value will be in the gravest peril.” At the subsequent inquiry, it was revealed that the letter had been written in November and held by Jameson for release whenever an Uitlander rising signalled him to come. When there was no Uitlander rising and Jameson decided to go anyway, he released what came to be known as the “women and children” letter. England, not knowing this, waited excitedly to see how this melodrama would turn out. A new Poet Laureate of England, Alfred Austin, hastily cobbled up suitable doggerel:

There are girls in the gold-reef city,18

There are mothers and children too!

And they cry, “Hurry up! for pity!”

So what can a brave man do?

The public cheered, but the British government promptly repudiated Jameson. The Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, had been dressing for a ball at his house in Birmingham when a messenger brought him the news. Chamberlain immediately took a train for London, arriving before dawn on December 31. A stream of cables flowing from his office that day called the raid “an act of war,”19 demanded that the raiders be summoned back, and offered his cooperation to President Kruger in making “a peaceful arrangement...20 which would be promoted by the concessions that I am assured you are ready to make.” Chamberlain worried most about reaction to the raid in Germany. “If it [the raid] were supported by us,”21 he said to Lord Salisbury, “it would justify the accusation by Germany and other powers that, having first attempted to set up a rebellion in a friendly state and having failed, we had then assented to an act of aggression.”

Chamberlain’s worries were well founded. The Transvaal Republic had always been a favorite of the German Empire: “a little nation which was Dutch—and22 hence Lower Saxon-German in origin—and to which we were sympathetic because of the racial relationship,” the Kaiser explained in his memoirs. In 1884, Paul Kruger, fresh from London where he had signed the Convention specifically prohibiting his country from making treaties without British approval, had arrived in Berlin and called on Bismarck. “If the child is ill,”23 Kruger observed, “it looks around for help. This child begs the Kaiser to help the Boers if they are ever ill.” Bismarck, aware of the terms of the London Convention, was noncommittal.

German influence in the small republic grew quickly. Following the discovery of gold in 1886, fifteen thousand Germans swarmed into the Transvaal; German businessmen established branches in Pretoria and an energetic German Consul, Herr von Herff, missed no opportunity to stress German ties to the Transvaal. A railroad from Pretoria to the sea through the Portuguese colony of Mozambique was under construction, largely supported by German capital (making it, thus, entirely independent of British control). The Portuguese port of Lourenço Marques on Delagoa Bay where the new railway reached the Indian Ocean became a steamship terminus for the North German Lloyd and Hamburg-America lines.

From time to time, British diplomats, worried about encouragement given Boer aspirations, reminded their German colleagues of the 1884 Convention. This offended the Kaiser. “To threaten us24 when they need us so badly in Europe,” he scoffed in October 1895. In 1895, German behavior stirred English suspicions. On January 27, the Kaiser’s birthday, the German Club of Pretoria entertained President Kruger. Herr von Herff assured Kruger that Germany cared about the fate of the Boer state. Kruger again cast his state in the role of a child. “Our little republic25 only crawls about among the great powers,” he said, “but we feel that if one of them wishes to trample on us, the other tries to prevent it.” Germany, he proclaimed, “was a grown up power that would stop England from kicking the child republic.” Sir Edward Malet, the British Ambassador in Berlin, protested this language to Marschall, the German Secretary of State. Marschall listened to Malet and retorted that the trouble in Africa was caused not by the Boers, but by the aggressive behavior of Cecil Rhodes. In July 1895, the Pretoria-to-Indian Ocean Railway was opened. William II telegraphed his congratulations and three German cruisers dropped anchor in Delagoa Bay.

In the autumn of 1895, rumors of an Uitlander rising spread to Europe. Malet, about to retire, used a final call on Marschall to warn of the danger of further encouragement of Boer aspirations. Marschall replied that, at the very least, the status quo must be maintained; any attempt to achieve Rhodes’ dream of uniting the Transvaal, economically or politically, into British South Africa would be “contrary to German interest.”26 The British and German press became belligerent. “The status27 [of the Transvaal to Great Britain] is one of vassal to suzerain,” proclaimed The Times. “We will wash28 our own dirty linen at home without the help of German laundresses,” growled the Daily Telegraph. Germany “needed no instruction29 as to the extent of her interests in South Africa,” declared the Vossische Zeitung. “The Transvaal has a right to turn to Germany for support. The republic is in no sense an English vassal.” When William II received Marschall’s report of his talk with Malet, he flared with indignation. At a diplomatic reception, he snagged the British military attaché and complained that Malet “had gone so far30 as to mention the astounding word ‘war.’... For a few square miles full of niggers and palm trees, England had threatened her one true friend, the German Emperor, grandson of Her Majesty, the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, with war.”

Then, on December 30, Herr von Herff telegraphed the Wilhelmstrasse that the raid had begun. He urged that a naval landing party from the ships in Delagoa Bay be brought by rail to Johannesburg to protect German citizens and property. On December 31, Hatzfeldt was instructed to ask officially whether the British government approved of the raid. If the answer were yes, he was to demand his passport and sever diplomatic relations. When Hatzfeldt called on Salisbury, he was assured that the government had nothing to do with the raid, was doing everything possible to suppress it, and recognized the dangers posed to the interests of other European powers in the Transvaal. Hatzfeldt returned to his embassy and cabled Berlin that the British government was not only not responsible for the raid, but was hugely embarrassed by it. In Berlin, Sir Frank Lascelles, the new British ambassador, delivered the same message, declaring that the raiders were “rebels” and that Jameson had been sternly commanded to withdraw.

In Berlin, however, the Kaiser was in a state of frenzied excitement. The Jameson Raid, following what he perceived as Lord Salisbury’s rudeness the preceding summer, seemed evidence of a deliberate British policy of patronizing and ignoring German interests and the German Emperor. On January 1, General von Schweinitz described his Imperial master as “absolutely blazing31 and ready to fight England.” The following day, the Prussian War Minister, General von Schellendorf, had an interview with the Kaiser during which William became so hysterical and violent that the War Minister told Prince Hohenlohe that “if it had been anyone else,32 he would have drawn his sword.” That evening, still agitated, William wrote to the Russian Emperor, Nicholas II: “Now suddenly33 the Transvaal Republic has been attacked in a most foul way, as it seems without England’s knowledge. I have used very severe language in London... I hope all will come right, but, come what may, I shall never allow the British to stamp out the Transvaal.”

Later that night, after the Kaiser’s message had been telegraphed to St. Petersburg, news of Jameson’s surrender reached Berlin. William, pleased, was still determined to strike a blow at England. At ten o’clock on the morning of January 3, the Emperor arrived at the Chancellor’s palace in the Wilhelmstrasse accompanied by Admirals Senden, Hollmann, and Knorr. Hohenlohe, the seventy-six-year-old Chancellor, and Marschall, the State Secretary, were there to receive them. Holstein and Kayser, Director of the Colonial Section, waited in a nearby room. “His Majesty,”34 Marschall wrote later, “developed some weird and wonderful plans. Protectorate over the Transvaal. Mobilization of the Marines. The sending of troops to the Transvaal. And, on the objection of the Chancellor, ‘That would mean war35 with England,’ H.M. says, ‘Yes, but only on land.’” The admirals doubted that Britain would be willing to fight Germany only on land in South Africa while observing peace in Europe and on the high seas. Discussion wandered. Someone suggested sending Colonel Schlee, Governor of German East Africa, disguised as a lion hunter, to Pretoria where he would offer himself as military Chief of Staff to President Kruger. Eventually Marschall, seeking to tone down the response, proposed that the Kaiser send a congratulatory telegram to President Kruger. William agreed and Marschall left the room to draft the message. Holstein, sensing danger, expressed misgivings, but Marschall silenced him quickly: “Oh, no, don’t you interfere.36 You have no idea of the suggestions being made in there. Everything else is even worse.” A telegram, actually drafted by Kayser, was sent back into the room, where it was approved. Couched as a personal message from the German Emperor to the Boer President, it read: “I express my sincere congratulations37 that, supported by your people without appealing for the help of friendly Powers, you have succeeded by your own energetic action against armed bands which invaded your country as disturbers of the peace and have thus been able to restore peace and safeguard the independence of the country against attacks from outside.” William made one change to stiffen the language: congratulating the President on safeguarding “the prestige of the country” was changed to “the independence” of the country. “I express to Your Majesty38 my deepest gratitude for Your Majesty’s congratulations. With God’s help we hope to continue to do everything possible for the existence of the Republic,” Kruger wrote back.

In Germany, the telegram was acclaimed. “Nothing that the government has done39 for years has given as complete satisfaction,” declared the Allgemeine Zeitung. Marschall exalted over the “universal delight40 over the defeat of the English.... Our press is wonderful. All the parties are of one mind, and even Auntie Voss [the Radical Vossische Zeitung] wants to fight.” The euphoria was short-lived. Bismarck called it “tempestuous.”41 Bülow described it as “crude and vehement.”42 Hatzfeldt “tore his hair43 over the incomprehensible insanity” that had overtaken the Wilhelmstrasse and was on the verge of resignation. Holstein, writing in 1907 after his retirement, regarded the telegram as the real beginning of Anglo-German antagonism: “England, that rich and placid nation,44 was goaded into her present defensive attitude towards Germany by continuous threats and insults on the part of the Germans. The Kruger telegram began it all.”

The English immediately wanted to know whether the telegram was merely an impulsive message from the Kaiser or an official statement by the German government. On January 4, the day after the telegram was sent, the Empress Frederick asked this question of Hohenlohe at lunch. The Chancellor “answered45 that it certainly was in accordance with German public feeling at this moment. From which,” the Empress wrote to her mother and brother in England, “I gather that the telegram was approved.” Subsequently, Marschall took the Times correspondent in Berlin aside and told him that the telegram was “eine Staats-Aktion”46 (an official act of state).

In subsequent years, each of the participants in the January 3 meeting took pains to show that the action was forced upon him against his better judgment. Holstein supported Marschall, describing the telegram as “an expression of the Kaiser’s annoyance,47 the result of disagreements of a personal nature which had arisen between the Kaiser and Lord Salisbury a few months previously during a visit to England.... Seeking an outlet for his resentment, he [William] seized on the first opportunity which was the Jameson Raid.”48

The Kaiser’s story changed over time. When the telegram was published and all Germany was shouting its approval, William spoke and acted as if he were the sole author. Later, in his memoirs, William attempted to shift responsibility: “The Jameson Raid caused great and increasing excitement in Germany.... One day, when I had gone to my uncle, the Imperial Chancellor, for a conference... Baron Marschall suddenly appeared in high excitement with a sheet of paper in his hand. He declared that the excitement among the people—in the Reichstag even—had grown to such proportions that it was absolutely necessary to give it outward expression and that this could best be done by a telegram to Kruger, a rough draft of which he had in his hand.

“I objected to this and was supported by Admiral Hollmann. At first the Imperial Chancellor remained passive in the debate. In view of the fact that I knew how ignorant Baron Marschall and the Foreign Office were of English national psychology, I sought to make clear to Baron Marschall the consequences which such a step would have among the English; in this, likewise, Admiral Hollmann seconded me. But Marschall was not to be dissuaded.

“Then, finally, the Imperial Chancellor [Prince Hohenlohe] took a hand. He remarked that I, as a constitutional ruler, must not stand out against the national consciousness and against my constitutional advisers; otherwise there was danger that the excited attitude of the German people, deeply outraged in its sense of justice and also in its sympathy for the Dutch, might cause it to break down the barriers and turn against me personally. Already, he said, statements were flying about among the people; it was being said that the Emperor was, after all, half an Englishman, with secret English sympathies; that he was entirely under the influence of his grandmother, Queen Victoria, that the dictation emanating from England must cease once and for all.... In view of all this, he continued, it was his duty as Imperial Chancellor, notwithstanding the fact that he admitted the justification of my objections, to insist that I should sign the telegram in the general political interest and, above all else, in the interest of my relationship to my people. He and Herr von Marschall, he went on, in their capacity of my constitutional advisers would assume full responsibility for the telegram and its consequences.... Then I tried again to dissuade the ministers from their project; but the Imperial Chancellor and Marschall insisted that I should sign, reiterating that they would be responsible for the consequences. It seemed to me that I ought not to refuse after their presentation of the case. I signed.

“After the Kruger dispatch was made public the storm broke in England as I had prophesied. I received from all circles of English society, especially from aristocratic ladies unknown to me, a veritable flood of letters containing every possible kind of reproach; some of the writers did not hesitate even at slandering me personally and insulting me....”

England’s reaction to the Kruger Telegram was first amazement, then overwhelming hostility. The Kaiser implicitly had endorsed the Transvaal’s “independence” and, by congratulating Kruger on repelling the raid “without the help of friendly powers,” had seemed to suggest that such help would have been—or in the future might be—available. “The nation will never forget49 this telegram,” proclaimed the Morning Post. “England will concede nothing50 to menaces and will not lie down under insult,” said The Times. Windows of German shops were smashed and German sailors were attacked on the Thames docks. The 1st Royal Dragoons, of which the Kaiser was the Honorary Colonel, took down the Imperial portrait and rehung it with its face to the wall. Satirical and ribald songs about the German Emperor dominated the London music halls. A Times editorial on January 7 restated Britain’s position: “With respect to the intervention51 of Germany in the affairs of the Transvaal... we adhere to the Convention of 1884 and we shall permit no infraction of it by the Boers or anyone else.... Great Britain must be the leading power in South Africa. She will not suffer any policy calculated to lessen her predominance.” The following day the government announced the formation of a naval “Flying Squadron” of two battleships and four cruisers. The object, Parliament heard, was “to have an additional squadron52 ready to go anywhere either to reinforce a fleet already in commission or to constitute a separate force to be sent in any direction where danger may exist.” In fact, the “Flying Squadron” got no farther than a cruise in the Irish Sea. Later, Britain reinforced its point with three British cruisers, which arrived in Delagoa Bay to shadow the three German warships already in the harbor.

The Royal Family disagreed as to how to react to “this most gratuitous act53 of unfriendliness,” as the Prince of Wales described the telegram to his mother. “The Prince would like to know what business the Emperor had to send any message at all. The South African Republic is not an independent state... it is under the Queen’s suzerainty.” The remedy the Prince urged on his mother was to give the Emperor “a good snubbing.” The Queen chose otherwise, deciding to deal with the Kaiser as an unruly grandson. “Those sharp, cutting answers54 and remarks only irritate and do harm, and in sovereigns and princes should be carefully guarded against,” she wrote to her son. “William’s faults come from impetuousness as well as conceit, and calmness and firmness are the most powerful weapons in such cases.” On January 5, from Osborne, Queen Victoria wrote a grandmotherly letter:

“My dear William...55 I must now touch upon a subject which causes me much pain and astonishment. It is the telegram you sent to President Kruger which is considered very unfriendly towards this country, not that you intended it as such I am sure—but I grieve to say it has made a most unfortunate impression here. The action of Dr. Jameson was, of course, very wrong and totally unwarranted, but considering the very peculiar position in which the Transvaal stands towards Great Britain, I think it would have been far better to have said nothing.” Lord Salisbury, receiving a copy of the Queen’s letter, advised her that the letter “is entirely suited,56 in Lord Salisbury’s judgement, to the occasion and hopes it will produce a valuable effect.” At the same time, Queen Victoria asked the Prime Minister to “hint to our respectable papers57 not to write violent stories to excite the people. These newspaper wars often tend to provoke war, which would be too awful.”

William’s reply to the Queen on January 8 was a blend of deference and evasion:

Most beloved Grandmama:58

Never was the Telegram intended as a step against England or your Government.... We knew that your Government had done everything in its power to stop the Freebooters, but that the latter had flatly refused to obey and, in a most unprecedented manner, went and surprised a neighboring country in deep peace.... The reasons for the Telegram were 3-fold. First, in the name of peace which had been suddenly violated, and which I always, following your glorious example, try to maintain everywhere. This course of action has till now so often carried your so valuable approval. Secondly, for our Germans in Transvaal and our Bondholders at home with our invested capital of 250–300 millions, which were in danger in case fighting broke out in the towns. Thirdly, as your Government and Ambassador had both made clear that the men were acting in open disobedience to your orders, they were rebels. I, of course, thought that they were a mixed mob of gold diggers quickly summoned together, who are generally known to be strongly mixed with the scum of all nations, never suspecting there were real English gentlemen or Officers among them.

Now, to me, Rebels against the will of the most gracious Majesty the Queen, are to me the most execrable beings in the world, and I was so incensed at the idea of your orders having been disobeyed, and thereby Peace and the security also of my Fellow Countrymen endangered that I thought it necessary to show that publicly. It has, I am sorry to say, been totally misunderstood by the British Press. I was standing up for law, order, and obedience to a Sovereign whom I revere and adore.... These were my motives and I challenge anybody who is a Gentleman to point out where there is anything hostile to England in this....

I hope and trust this will soon pass away, as it is simply nonsense that two great nations, nearly related in kinsmanship and religion, should stand aside and view each other askance with the rest of Europe as lookers-on. What would the Duke of Wellington and old Blücherfn2 say if they saw this?

Salisbury favored letting the incident drop and advised the Queen to accept William’s explanations “without enquiring too narrowly59 into the truth of them.” From the perspective of British politics, the Emperor had done the Salisbury Cabinet a favor. Jameson’s caper had brought discredit on the government; many believed that the Colonial Secretary was personally involved. By bursting onstage in the middle of this drama, the German Emperor diverted attention to himself. Ironically, it was Rhodes who best explained this to the Kaiser. Visiting Berlin in 1899 in connection with the laying of a telegraph line through German East Africa, he was invited to lunch at the Castle. (The Empress had written to Bülow, “I should like to hear60 from you how I ought to treat Cecil Rhodes... whether rather coldly or whether one ought to be particularly friendly to him. My own choice would be for the former.”) William, impressed by the great conquistador, listened tolerantly as Rhodes described how the Kruger Telegram had saved him. “You see, I was a naughty boy61 and you tried to whip me. Now my people were quite ready to whip me for being a naughty boy, but directly you did it, they said, ‘No, if this is anybody’s business, it is ours.’ The result was that Your Majesty got yourself very much disliked by the English people and I never got whipped at all!”

Rhodes may have considered himself unwhipped, but both he and Jameson were punished for the raid. Jameson and his five chief officers were brought to London and tried at the Old Bailey for infringement of the Foreign Enlistment Act. In the months before the trial and even during the nine-day process in July 1896, the defendants remained free and Jameson was the toast of the capital. Arthur Balfour, the Government Leader in the House of Commons, declared that he “should probably have joined Jameson62 had he lived there.” Margot Tennant Asquith, wife of the future Liberal Prime Minister, H. H. Asquith, sighed that “Dr. Jim had personal magnetism63 and could do what he liked with my sex.” Although The Times urged that Jameson’s sin was only “excess of zeal”64 and Lord Chief Justice Russell had to suppress pro-Jameson courtroom demonstrations during the trial, the verdict was guilty. Jameson was sentenced to fifteen months. (The officers, given shorter terms, were stripped of their commissions in the Regular Army.) Jameson went to a comfortable jail, but he moped, declined in health, and was sent home with a Queen’s Pardon after only four months. Eight years later, in 1904, he became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. In 1911, King George V made him a baronet, and the following year, Sir Leander Starr Jameson came back to England for good. He lived with his brother for five years and died at sixty-four, in 1917. From his sentencing to his death, he refused to speak about the raid.

Of greater political significance than the guilt of Jameson was the extent of the involvement of Cecil Rhodes and Joseph Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary. These questions were the subject of a five-month inquiry by a Select Committee of the House of Commons in the spring of 1897. The raiders had been captured carrying copies of cipher telegrams which proved Rhodes’ complicity in the proposed Uitlander uprising and the preparations for the raid. He had not authorized Jameson’s decision to proceed; indeed, he had sent a cable halfheartedly telling him not to go. When Jameson went anyway, Rhodes acted as if he were horrified. “Old Jameson65 has upset my applecart,” he said. “Twenty years we have been friends and now he goes and ruins me.” Rhodes immediately resigned as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony and Managing Director of the Consolidated Gold Fields Company. In London, he appeared for six days before the Select Committee. He shouldered all the blame for the planning of the raid; when the Committee asked whether it was as Prime Minister or Managing Director that he had organized the incursion, Rhodes replied, “Neither.”66 He had done it solely “in my capacity as myself.”

The Committee found it impossible to establish that Chamberlain had prior knowledge of the raid. In the Colonial Secretary’s favor was his immediate condemnation of the raid once he learned it was under way. While Rhodes was censured, Chamberlain and all other members of the Cape and British governments were exonerated. A few days after the inquiry ended, the House of Commons was shocked to find the Colonial Secretary rising to offer Cecil Rhodes a public testimonial. “As to one thing,67 I am perfectly convinced,” Chamberlain said. “That while the fault of Mr. Rhodes is about as great a fault as a politician or a statesman can commit, there has been nothing proved—and in my opinion there exists nothing—which affects Mr. Rhodes’s personal position as a man of honor.” (Cynics suggested that Rhodes had wrung these words from Chamberlain by threatening to disclose hitherto unseen documents.)

Rhodes lived only six years after the raid. He suffered from cardiovascular disease, which he helped along by eating huge slabs of meat, drinking throughout the day, and smoking incessantly. His body near the end was bloated, his cheeks blotched and flabby, his eyes watery. His high-pitched voice became almost shrill; his handshake, offered with only two fingers of the hand extended, was weak; his letters, which had always ignored punctuation, left out words to the point of incoherence. He spent most of his time in his spacious Dutch farmhouse mansion, called Groote Schuur, at the foot of Table Mountain outside Cape Town. The rooms were beamed and paneled in dark teak and hung with African shields and spears. His vast bathroom of green and white marble boasted an eight-foot tub carved from solid granite. On his bookshelves he had placed the works of all the classical authors mentioned by Gibbon in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Rhodes had ordered these authors translated for himself at a cost of £8,000. On his bedroom wall, Rhodes had hung a portrait of Bismarck.

In 1896, when Groote Schuur was gutted by fire, Rhodes was told that there was bad news. He knew that Jameson was ill; now, his face white, he said, “Do not tell me68 that Jameson is dead.” When he heard about the fire, he flushed in relief. “Thank goodness,”69 he said. “If Dr. Jim had died, I should never have got over it.” Jameson was at Rhodes’ side in March 1902 when the Colossus, at forty-eight, met his own death. His last words were “So little done,70 so much to do.”

Tension between the British and German governments ebbed quickly, although Lord Salisbury comprehended the potential danger that had been implicit in the situation. “The Jameson Raid71 was certainly a foolish business,” he said to Eckardstein. “But an even sillier business... was the Kruger Telegram.... War would have been inevitable from the moment that the first German soldier set foot on Transvaal soil. No government in England could have withstood the pressure of public opinion; and if it had come to a war between us, then a general European war must have developed.” As it was, the raid and the telegram altered the relationship between Great Britain and Imperial Germany. In the popular view of Englishmen, the raid was a daring effort to protect legitimate British interests. The Kaiser’s action had taken the British people entirely by surprise. Until publication of the telegram, Britons had traditionally looked upon France as the potential antagonist. The German Empire, ruled by the Queen’s grandson, was assumed to be England’s friend. The telegram indicated an unsuspected animosity. Feelings softened as time passed, but a residue of suspicion remained. The Princess of Wales declared to a friend that “in his telegram to Kruger,72 my nephew Willy has shown us that he is inwardly our enemy, even if he surpasses himself every time he meets us in flatteries, compliments, and assurances of his love and affection.” In Rome, Sir Francis Clare Ford, the British Ambassador, warned his German colleague Bernhard von Bülow that “England will not forget73 this box on the ear your Kaiser has given her.” When Bülow spoke of the many ties between the two countries, Ford explained that it was “just because of these many and intimate ties that the English people will not forgive your Kaiser this affront. The Englishman feels as a gentleman at a club might feel if another member—say his cousin with whom he played whist and drunk brandy and soda for many years—suddenly slapped his face.”

The explosion of British anger, thoroughly reported in the German press, created its own backlash in Germany. One beneficiary was Tirpitz, who had opposed the sending of the telegram as unrealistic in view of Germany’s impotence at sea. What could Germany have done, he asked, if Hatzfeldt had taken back his passport? What could fifty, or a hundred, or a thousand German marines or soldiers do in Africa as long as Britain controlled the sea? Mahan’s thesis, that world power requires sea power, was glaringly displayed. “The incident may have its good side,”74 Tirpitz wrote to General von Stosch, his former superior as Navy Minister, “and I think a much bigger row would actually have been useful to us... to arouse our nation to build a fleet.” Years later, in his memoirs, the Grand Admiral concluded that “the outbreak of hatred,75 envy, and rage which the Kruger Telegram let loose in England against Germany contributed more than anything else to open the eyes of large sections of the German people to our economic position and the necessity for a fleet.”

fn1 Today, Northern and Southern Rhodesia have become, respectively, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

fn2 The commanders of the allied British and Prussian armies at Waterloo.