Alfred von Kiderlen-Waechter, Germany’s most significant Imperial State Secretary for Foreign Affairs after Bernhard von Bülow, was born in Stuttgart in 1852. His father, a banker, became a senior official at the Württemberg Court and was about to be ennobled when he died unexpectedly; the honor was given posthumously and Kiderlen, his mother, and his siblings acquired the “von.” At eighteen, Alfred volunteered for service in the Franco-Prussian War. After the war, he finished University and law school and entered the Foreign Service. His first foreign assignment was to St. Petersburg, where he arrived in 1881. A large, florid, fair-haired young man whose face was slashed with student duelling scars, he became known as a heavy drinker and troublemaker. Young bachelors from the embassies of several European nations gathered nightly at a regular table in a French restaurant to gossip, laugh, and carouse. Much ribbing passed back and forth, but none of it in Kiderlen’s direction. Any teasing pointed at him was likely to provoke growls and perhaps a threat of swords or pistols.

Kiderlen spent four years in St. Petersburg, two in Paris, and two in Constantinople. He attracted Holstein’s attention. Holstein’s first impression was that Kiderlen was “a typical Württemberger1 with a gauche exterior and a crafty mind,” but in time the suspicious older man came to trust and value the younger. Bülow, who always disliked other men of talent in the diplomatic service, declared that Kiderlen was “a tool of Holstein,”2 but he admitted that Kiderlen had useful qualities. “Kiderlen was to Holstein3 what Sancho Panza was to Don Quixote,” Bülow announced. “He was incapable of enthusiasm and of any idealistic conceptions. His feet were always firmly on the ground but he had a very strong feeling for the prestige and advantages of the firm and he watched the competitors with great vigilance.” During the Caprivi Chancellorship, when the inexperience of both the Chancellor and State Secretary Marschall left Holstein supreme at the Wilhelmstrasse, Kiderlen flourished as head of the Near Eastern Section. By 1894, his prominence and his close ties to Holstein had been noted by Kladderadatsch, a satirical journal favorable to Bismarck and hostile to his enemies. When the paper attacked Holstein, Eulenburg, and Kiderlen, bestowing on each an unfavorable nickname (Holstein was the “Oyster-fiend,”4 Eulenburg the “Troubadour,” and Kiderlen “Spätzle”—Dumpling—after the South German dish of which the Württemberger was fond), Kiderlen challenged the editor to a duel, pinked him in the right shoulder, and was sentenced to four months in the fortress of Ehrenbreitstein. He was released after two weeks, his career undamaged. In 1895, as Ambassador to Denmark, he artfully deflected a riot from the German Embassy. Slipping out into the crowd, he pointed to a harmless storehouse, shouted at the top of his lungs, and began hurling stones at the storehouse windows.

In 1888, Bismarck selected Kiderlen to accompany the Kaiser as the Foreign Ministry representative on board the Hohenzollern cruises to Norway. William liked the rough, intelligent Württemberger, who told good jokes and seemed to enjoy the exuberant pranks and crude horseplay that characterized those nautical holidays; the invitation to Kiderlen was renewed every year for a decade. Then, in 1898, his participation in the Imperial cruises—and very nearly his career—terminated. In fact, Kiderlen had been appalled by the false heartiness and schoolboy intrigue practiced on board the yacht and he wrote of his feelings, privately, to State Secretary Marschall. When Marschall departed Berlin for Constantinople in 1897, he failed to clean out his office and the new State Secretary, Bülow, discovered the letters in the files. They found their way to the Emperor, who read Kiderlen’s biting descriptions of behavior on board the yacht, of rudeness to the Prince of Wales, of boorishness at the Royal Yacht Squadron at Cowes. Kiderlen was banned from the yacht and the Kaiser’s presence and, as soon as a place could be found for him, exiled from Berlin. For the next ten years—from the age of forty-eight to the age of fifty-eight—he labored at the Embassy in Bucharest. One after the other, less able men—first Tschirschky, then Schoen—went to the top of the Foreign Ministry while one of the most vigorous and experienced men in the diplomatic service, trained by Bismarck and Holstein, was stuck in a Balkan cul de sac.

In Romania, Kiderlen had no difficulty expressing his contempt for the post he held. Every year on New Year’s Eve, King Carol held a reception for diplomats, followed by a court ball, the most important diplomatic event of the year in his country. Every year, Kiderlen departed on Christmas leave before the ball, declaring to any Romanians who would listen that the King was unwise to make plans which so seriously conflicted with his own holiday arrangements.

In Kiderlen’s time, the principal social gatherings at the German Legation in Bucharest were rowdy “beer evenings” during which male members of the German colony gathered to carouse and sing in a manner reminiscent of student days. Ladies of the German Colony and the diplomatic corps never visited the German Legation because of the private life of the German Minister. Kiderlen had a mistress, Frau Hedwig Krypke, a widow two years younger than himself with whom he lived the last eighteen years of his life. She was handsome and discreet; she lived with him in Copenhagen and Bucharest and when he was State Secretary, but he never showed any intention of making her his wife. As a result, she—and to some extent, he—was ostracized in Berlin and in the foreign capitals in which he served; the Kaiserin was particularly incensed that this unrepentant sinner should rise so high in the Imperial government. Nevertheless, Kiderlen robustly defied convention and managed to maintain both his career and his liaison with Frau Krypke.

The Wilhelmstrasse was not so rich in talented diplomats that it could afford permanently to ignore Kiderlen’s qualities. Twice during his long exile in Bucharest Kiderlen was temporarily transferred to the larger post at Constantinople to substitute for Marschall when Marschall was on leave. In 1908, when Baron Schoen, the State Secretary, fell ill, Kiderlen was summoned to Berlin to fill in. “I am to pull5 the cart out of the mud and then I can go,” grumbled the Württemberger. Kiderlen remained unforgiven by his sovereign; when he went to the Palace to pay his respects, the Kaiser shook hands without a word. Kiderlen’s brief tenure as a substitute was crowded with significant events. He arrived at the peak of the Bosnian Crisis and helped to force a Russian retreat without war. With Jules Cambon (Paul Cambon’s brother), the French Ambassador in Berlin, he negotiated a new Franco-German agreement on Morocco, reinforcing guarantees to German commerce and investments in that country. He stumbled when Bülow, heavily criticized in the Reichstag for his handling of the Daily Telegraph affair, put the Acting State Secretary in front of the deputies to distract attention from himself. Kiderlen’s speech was not a success and his attempt to explain the working of the Foreign Ministry, along with his proposal to increase efficiency by increasing staff, provoked “a general outburst of hilarity.”6 Bülow later mocked his lieutenant’s distress, comparing the Reichstag’s contemptuous mirth to that of a band of students or young regimental officers baiting an awkward new colleague. “Kiderlen’s debacle,” Bülow noted, was helped along by “his pronounced Swabian accent7 and... the extraordinary yellow waistcoat he wore.” Kiderlen himself was serene throughout; he did not care what either the Chancellor or the Reichstag thought of him. In his view, Bülow was finished as Chancellor and parliament had neither the competence nor the right to participate in the making of foreign policy.

Bülow’s departure cleared the way for Kiderlen’s permanent return to Berlin. By 1909, the Chancellor, far more than the exiled Minister in Bucharest, was the object of the Kaiser’s displeasure. When Bethmann-Hollweg, who knew nothing of foreign affairs, was chosen to succeed Bülow, the outgoing Chancellor advised the Kaiser that the Foreign Ministry would have to be given to someone of greater ability than the amiable Schoen. William did not think so. “Just leave foreign policy to me,”8 he said to Bülow. “I’ve learned something from you. It will work out fine.” Bethmann was aware of his own limitations, however, and as soon as he took office, an urgent summons went to Kiderlen in Bucharest: “The new Chief9 is extremely anxious to meet you.” Schoen did not mind being replaced. “Bethmann is a soft nature,”10 he observed, “and I am also rather flabby. With us two a strong policy is impossible.” Nevertheless, it required almost a year and a rising chorus of voices, including that of the Crown Prince, to overcome the Kaiser’s opposition. In June 1910, when Kiderlen at last was appointed State Secretary, William warned Bethmann, “You are putting a louse in the pelt.”11

In office, Kiderlen took charge in a manner which brooked no opposition. Subordinates were soon referring to him as Bismarck II. He ignored his own ambassadors in foreign capitals, including two former State Secretaries, Marschall in Constantinople and Schoen, who had been sent to Paris; he himself handled all negotiations with the foreign ambassadors posted in Berlin. When he discovered that the Kaiser was communicating privately with Metternich in London, he stormed and threatened to resign. William’s habit of calling at the Wilhelmstrasse every day to see what was going on vexed Kiderlen, and he parcelled out information to the sovereign only in the briefest form. He had left neither his gruff manner nor his tactlessness behind in Bucharest. Once, he announced that he had never set foot beyond the European continent. “Really?” said the American Ambassador. “No, thank God, never!”12 replied the State Secretary. Kiderlen’s relationship with Bethmann began with mutual respect, then eroded as the State Secretary decided that the Chancellor’s grasp of foreign affairs would never be more than amateurish. Bethmann referred to Kiderlen as “Dickkopf” (“Thick Head”) and Kiderlen to the Chancellor as “Regenwurm”13 (“Earthworm”). At times, Kiderlen treated Bethmann like a subordinate, saying that he could not give details of foreign-policy issues to the Chancellor because Bethmann simply would not understand them. When Bethmann fussed, Kiderlen offered to resign. When foreign ambassadors complained that Kiderlen told them nothing, the Chancellor replied, “So. Do you think he tells me more?”14 Nor could Bethmann find sympathy for his troubles with Kiderlen by turning to the Kaiser; William was quick to remind that he had warned against putting eine Laus in den Pelz.

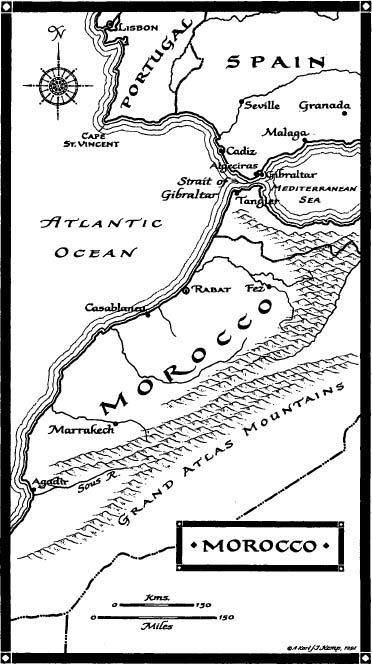

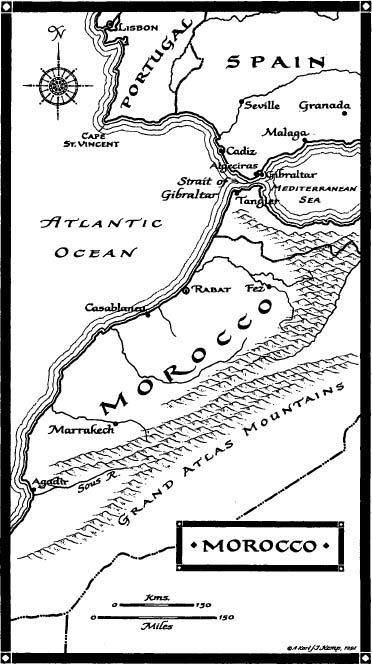

Morocco, which had brought Europe close to the precipice in 1905, was a source of permanent turmoil in international affairs. On paper, the Act of Algeciras had endorsed the independence of the Sultan’s realm and guaranteed an open door for the commerce of all nations. In fact, France had assumed a primary political role, although not the full protectorate which she desired, while Germany had been guaranteed commercial rights and access. Great Britain, whose trade in Morocco was larger than that of either France or Germany, was content to remain generally mute while giving support to her Entente partner. Despite this agreement, friction between France and Germany continued. In 1908, German consular officials helped German deserters to escape from the French Foreign Legion through Casablanca; the French found out and dealt roughly with the offending diplomats. Berlin was enraged and there was talk of war. In January 1909, Kiderlen, then substituting in Berlin for Schoen, negotiated a new bilateral treaty with Jules Cambon, the French Ambassador. In a declaration signed February 8, 1909, the German government recognized “the special political interests15 of France in Morocco” and declared itself “resolved not to thwart those interests.” In return, the French government promised “to safeguard the principle of economic equality and consequently not to obstruct German commercial and industrial interests in the country.” Both parties were momentarily happy. Kiderlen was rewarded with a Sèvres dinner service to take back to Bucharest.

The détente in Morocco was short-lived. As France moved confidently ahead in the political sphere, assuming that the phrase “special political interests” gave her a free hand to deal with the Sultan, Germans complained that their businesses were not receiving the increased commercial concessions they felt were due. Southern Morocco, for example, was believed in Germany to be “exceedingly fertile”16 and “highly suitable for European settlement.” Treasures of iron and other ores were said to he beneath the surface, and these supposed riches had attracted the attention of major German firms. In 1909, the Düsseldorf metallurgical company of Mannesmann Brothers established a subsidiary, Marokko-Mannesmann, to explore and exploit the ores of southern Morocco. About the same time, Max Warburg created Hamburg-Marokko Gesellschaft to investigate the same opportunities. Although the region was closed by the Act of Algeciras to all international commerce, the German firms assumed that, with French cooperation, these limitations could be overcome. The French refused to cooperate. In December 1910, Bethmann rose in the Reichstag to warn, “Do not doubt17 that we will energetically defend the rights and interests of German merchants.” It did no good. Two months later a German diplomat reported that “in Casablanca,18 one can no longer escape the feeling of living in a purely French colony.”

Meanwhile, Sultan Abdul-Aziz, who had progressed from Gatling guns and bicycles to photography and collecting expensive watches, was overthrown in 1908 by his brother Mulai Hafid in a civil war which bankrupted the state treasury. In 1909, the new Sultan confronted claims, primarily French and Spanish, for damages during the fighting. The claims totalled sixteen times the Sultan’s annual revenue. To pay the debts, Mulai Hafid imposed new taxes; these stirred fresh discontent. In January 1911, a French officer was murdered. In April, the tribes near Fez, the capital, revolted and still another brother of Abdul-Aziz proclaimed himself Sultan. The French Consul in Fez reported that the situation was perilous and that the Europeans in the city were threatened with massacre. Under the Act of Algeciras, each of the Great Powers was permitted to intervene if the lives or property of its citizens were in danger. Accordingly, France informed the other powers that a French military column would be dispatched from Casablanca to Fez.

Always sensitive to any pretext the French might employ to enhance their political control of Morocco, Kiderlen warned Cambon on March 13 that complications would arise from French military action. On April 4, informed by Cambon that the Europeans of Fez were in danger, the State Secretary retorted that reports from the German Consul in that city gave no cause for alarm. On April 28, when Cambon announced that the situation was now so ominous that the Sultan had appealed for help, that France must rescue the Europeans but would quit the city as soon as order was ensured, Kiderlen told him soberly, “If you go to Fez,19 you will not depart. If French troops remain in Fez so that the Sultan rules only with the aid of French bayonets, Germany will regard the Act of Algeciras as no longer in force and will resume complete liberty of action.”

Kiderlen’s position was strong: Germany had commercial interests and treaty rights in Morocco; France clearly intended to alter the basis of her position in the country; France knew that Germany was entitled to consideration and compensation based on France’s action; yet no offer of compensation had been forthcoming. Kiderlen could, of course, simply continue to register complaints with Cambon and hope that, sooner or later, France would take cognizance of Germany’s appeals. The Wilhelmstrasse did not see this as the way great states responded when their interests were challenged. Nor was this course likely to appeal to the vociferous nationalists in the Reichstag and in the press. A solution was proposed in a memorandum, dated May 30, from Baron Langwerth von Simmern, whose Foreign Office responsibilities included Morocco: northern Morocco would soon be French in defiance of the Act of Algeciras, and France was legitimizing this action by claiming that its citizens were in danger in Fez. Why should Germany not use the same argument in southern Morocco? There were no German soldiers in the country, but the same effect could be achieved by sending one or several warships to protect the lives and property of German citizens in southern Morocco. A suitable port, Simmern suggested, was Agadir. Eventually, France and Germany would compromise and there would be a new division of Moroccan spoils, or France would compensate Germany by ceding a slice of the French Congo adjacent to the German colony of Cameroons. In the meantime, the warship’s presence would underscore Germany’s right to be heard. The memorandum was circulated and discussed. Bethmann had misgivings. He did not like the idea of sending ships. “And yet it will not work20 without them,” he admitted. Ultimately, he stepped back from accountability and left “full liberty of action21 and entire responsibility” to Kiderlen.

The German move was political, but it had to seem to be a protection of commercial interests. Accordingly, on June 19, Dr. Wilhelm Regendanz, the new managing director of Max Warburg’s Hamburg-Marokko Gesellschaft, was summoned to the Wilhelmstrasse and told to draw up a petition from German firms active in southern Morocco, appealing to the government for help from marauding natives. Regendanz was to collect signatures from as many firms as possible. His task was particularly delicate and arduous because he was not permitted to show the signers the document they were signing; the Foreign Ministry considered this a necessary precaution against leaks. In spite of this hindrance, Dr. Regendanz successfully collected the backing of eleven firms.

There was a snag in working out the scheme: at that moment there were no German citizens or commercial interests in southern Morocco. Despite the grandiose talk by the Mannesmann Brothers and the Hamburg-Marokko Gesellschaft, no German explorers had yet traveled to see the “exceedingly fertile”22 valley of the Sus or to test-bore the imagined ore deposits of the southern Atlas Mountains. Dr. Regendanz considered this only a temporary embarrassment. When the warship arrived at Agadir, he promised, endangered Germans would be there to welcome it.

Meanwhile, negotiations were proceeding with France. On June 11, Kiderlen having retreated to Kissingen for his annual cure, Cambon called on the Chancellor in Berlin. The Ambassador found Bethmann unusually agitated and talking of “extremely grave difficulties.”23 Cambon said jauntily that “no one can prevent Morocco24 falling under our influence one day,” but for the first time he spoke of compensation, something “which would allow German opinion to watch developments without anxieties.” Bethmann, nervously aware of the developing plan to send ships to Agadir, advised Cambon to “Go and see Kiderlen25 at Kissingen.” Cambon went, and at the spa on June 21 he told the State Secretary that he hoped the German Empire would not insist on a partition of Morocco because “French opinion would not stand for it.26 But,” he added significantly, “one could look elsewhere.”27 Kiderlen declared himself ready to listen to “offers.” Cambon replied that he was on his way to Paris and would discuss it with his government. On parting, Kiderlen said to the Ambassador, “Bring something back28 with you.”

The Cabinet to which M. Cambon was on his way to report was in exceptional confusion. There had been a frightful accident. At dawn on May 20, M. Ernest Monis, the Prime Minister, had been standing at the edge of a small airfield at Issy-les-Moulineaux, watching the start of a Paris-to-Madrid air race. One of the planes developed engine trouble on takeoff, barely rose from the ground, swerved, and plunged into the crowd of spectators. The Premier was struck in the face and chest by the propeller and rendered unconscious; the War Minister, standing next to him, was killed. For several days, M. Monis’s life was in danger, then, partially recovered but maimed, he attempted to direct the nation’s affairs from his bed. On June 27, he resigned and M. Joseph Caillaux, the Minister of Finance, stepped up to the Premiership. Caillaux, considered able but unscrupulous, was one of a group of international French financiers with close ties to Berlin, and it was expected that his foreign policy would be Franco-German rapprochement. As Foreign Minister, Caillaux chose M. de Selves, a local government official with no experience of foreign or even national affairs. Observers took this to mean that the Prime Minister meant to conduct foreign affairs himself.

Aware that the French government was in turmoil, State Secretary Kiderlen made up his mind. On June 24, after Cambon had departed for Paris, Kiderlen traveled to Kiel to report to the Kaiser and persuade William to dispatch the warship.

William sensed more acutely than Kiderlen or Bethmann that a new adventure in Morocco was likely once again to embroil Germany with England. The Kaiser had no wish to do this; now that his sinister uncle, “Edward the Encircler,” was gone, William felt cozily comfortable with his cousin “Georgie,” whom he could hector and intimidate as he did the Tsar. He accepted eagerly King George’s invitation to witness the unveiling of a statue of their mutual grandmother, Queen Victoria, in front of Buckingham Palace. On May 16, the Kaiser arrived with the Kaiserin and their nineteen-year-old daughter, Princess Victoria Louise. As always, William was exhilarated by British military pageantry: “The big space29 in front of Buckingham Palace was surrounded by grandstands... filled to overflowing. In front of them were files of soldiers of all arms and all regiments of the British Army... the Guards... the Highlanders.... The march past was carried out on the circular space, with all the troops constantly wheeling; the outer wing had to step out, the inner to hold back, a most difficult task for the troops. The evolution was carried out brilliantly; not one man made a mistake.” The public caught the good mood between the cousins. One night, the King took his guests to a play at the Drury Lane Theatre. Between acts a curtain was lowered which depicted a life-size King and Kaiser mounted on horseback, riding toward each other, saluting. The audience rose and cheered. Haldane, who had suggested giving a lunch for the German generals in the Kaiser’s party, was told that the Emperor himself would like to come. Haldane arranged an eclectic guest list including Lord Kitchener; the First Sea Lord, Sir Arthur Wilson; Lord Morley; Lord Curzon; Ramsay MacDonald, leader of the Labour Party; and the painter John Singer Sargent. William enjoyed himself, although he could scarcely believe that a British Minister of War could live in a house so small that the Emperor dubbed it the “Dolls’ House.”30

The Kaiser had been asked by Bethmann to bring up Morocco with his British cousin. Obediently, William asked whether King George did not agree that France’s policies seemed incompatible with the Algeciras Convention. The King’s reply was candid. “To tell the truth,”31 he said, “the Algeciras Convention is no longer in force and the best thing everyone can do is to forget it. Besides, the French are doing nothing in Morocco that we haven’t already done in Egypt. Therefore we will place no obstacles in France’s path. The best thing Germany can do is to recognize the fait accompli of French occupation of Morocco and make arrangements with France for protection of Germany’s commercial interests.” William listened and promised the King that, at least, “We will never make war32 over Morocco.” Returning home, he reported this conversation to the Chancellor, concluding that England would not oppose French occupation of Morocco and that if Germany meant to do so, she would have to do it on her own.

A month later, on June 21, when plans to send a ship had long been hatched, and Dr. Regendanz was gathering signatures from German firms appealing for help for their endangered interests, the Kaiser still was not aware of his Foreign Minister’s plans. William continued to say that he had no objection to greater French involvement in Morocco because “France would bleed33 to death there.” Constitutionally, the command to send a ship had to come from the Kaiser, the supreme warlord. Somehow, he would have to be told and persuaded. On June 26, William was on board the Hohenzollern attending the Lower Elbe Regatta, with Bethmann also on board and Kiderlen expected. When Kiderlen arrived, the two men tackled the Emperor. William balked; he was willing to accept expansion of the German Empire but had little stomach for a direct military challenge to France. He protested that sending a ship was too big a risk, that no one could predict the consequences, and that a step of such far-reaching importance should not be taken without consulting the nation. The Chancellor and the State Secretary persisted. “We will have to take34 a firm stand in order to reach a favorable result,” Kiderlen insisted. “We cannot leave Morocco35 to the French.... [Otherwise] our credit in the world will suffer unbearably, not only for the present, but for all future diplomatic actions.” In the end, the monarch who boasted to his relatives and in his marginalia that he, not his ministers, was the sole master of German foreign policy, reluctantly consented. In his memoirs, he disavows responsibility: “During the Kiel Regatta Week,36 the Foreign Office informed me of its intention to send the Panther to Agadir. I gave expression to strong misgivings as to this step, but had to drop them in view of the urgent representations of the Foreign Office.” From the Hohenzollern’s radio room, Kiderlen crisply telegraphed Berlin: “Ships approved.”37

A signal flashed from the German Admiralty to the gunboat Panther, then proceeding north off the West African coast, bound for home after a voyage around the Cape. Built for colonial service a decade before, the light-gray, two-stack Panther was not the ship the Kaiser would have chosen to advertise his powerful fleet. She was short, fat, and lightly armedfn1; her crew of 130 included a brass band; and her primary mission was impressing natives or bombarding mud villages rather than fighting other ships at sea. Suitable or not, Panther had been tapped and she entered the historical limelight on July 1, 1911, when she steamed slowly into the Bay of Agadir and dropped her anchor a few hundred yards from the beach.

The view from the ship was magnificent. A broad bay of sparkling blue water was framed by steep brown cliffs rising seven hundred feet from the sea. At the top stood the walls and towers of Agadir Castle, an imposing Portuguese bastion built centuries earlier, when Portugal reached out across the globe. Below, at sea level, in the small fishing village of Funti, people lived and worked in an ageless fashion. No Europeans and no sign of European life were present; the port had been closed to international shipping for many years.

One European was on the way. Doing his best, as instructed, to arrive before the warship sent to protect him, Herr Wilburg, subsequently nicknamed the “Endangered German,”38 was a representative of the Hamburg business consortium in Morocco. On June 28, he was in Mogador, seventy-five miles north of Agadir. Because all telegrams to Morocco had to be sent in French and French officials were free to read them, a code had to be worked out in which Wilburg’s instructions and destination were hidden in a seemingly innocuous text. Three telegrams were necessary, and it was not until the evening of July 1 that Wilburg was able to start. His journey was arduous and miserable. The heat which afflicted Europe that summer was even more intense in Africa. Wilburg found all the grass and shrubs burned up by the sun; he even found that goats had climbed into trees to escape the scorching rays. The road was no more than a track, sometimes only a few feet wide, winding through hills strewn with rocks and stones. On corniches along the sea, on one side he touched a cliff and on the other, he looked down on a precipitous drop. Caravans of mules and camels came toward him, forcing him to press his horse against the rock.

When Wilburg arrived at Agadir on the afternoon of July 4, the Panther had been at anchor for three days. Wilburg saw the warship, but was too exhausted to make contact. The next morning when he awoke, he saw that a second, larger German ship had entered the bay and anchored during the night. This was the 3,200-ton light cruiser Berlin, with ten four-inch guns and a crew of three hundred. Immediately, Wilburg tried to let his countrymen know that he was present. At first, he had no luck; the men on the Berlin took the man on the beach running up and down, waving his arms and shouting faint cries, for an excited native, perhaps with something to sell. The Admiralty had given strict orders that men were not to be landed without further instructions. Wilburg, seeing the men on the ships staring at him without apparent interest, became dispirited and stood motionless, looking back at the two gray ships lying silent in the bright sunlight. His posture identified him: suddenly an officer on the Panther was struck by the lonely figure on the beach standing with his hands on his hips. Africans did not employ this stance. A boat was launched and soon Wilburg, the “Endangered German,” was taken under the protection of the Imperial Navy. It was the evening of July 5.

News of the Panthersprung (panther’s leap) created a sensation in Europe. At noon on July 1, German ambassadors in all capitals delivered the following note to their host governments:

“Some German firms39 established in the south of Morocco, notably at Agadir and in the vicinity, have been alarmed by a certain ferment which has shown itself among the local tribes.... These firms have applied to the Imperial Government for protection for the lives of their employees and their property. At their request, the Imperial Government has decided to send a warship to the port of Agadir, to lend help and assistance, in case of need, to its subjects and employees, as well as to protect the important German interests in the territory in question. As soon as the state of affairs in Morocco has resumed its former quiet aspect, the ship charged with this protective mission will leave the port of Agadir.”

Within the Reich itself, Kiderlen’s move had overwhelming support. “Hurrah! A deed!”40 shouted the headlines of the Rheinisch Westfälische Zeitung. “Action at last,41 a liberating deed... Again it is seen that the foreign policy of a great nation, a powerful state, cannot exhaust itself in patient inaction.” Pan-Germans assumed that the partition of Morocco was at hand, that Germany would annex a piece of the seaboard. On June 12, the Crown Prince, a fervent nationalist, expressed this view to Cambon. Inviting the Ambassador to the Imperial box at the Grunewald Races, he spoke of Morocco as “un joli morceau,”42 adding, “Give us our share and all will be well.” On the day of the Panther’s leap, Arthur Zimmerman of the Foreign Office assured the Pan-German League, “We are seizing this region43 once and for all. An outlet for our population is necessary.” Kiderlen kept silent, refusing to reveal whether his goal was a piece of Morocco or a larger slice of territory somewhere else. Either way, the Panther’s spring would serve: “Little by little44 we will make ourselves at home in the ports and the hinterland and then at the right moment, attempt to come to an understanding with France on the basis of the division of Morocco or of compensation by a part of the French Congo.”

Jules Cambon, the French Ambassador in Berlin, was immediately affected by the sudden coup. A week before, he had left Kiderlen at Kissingen, having been asked to “bring back something” from Paris. In his own capital, he had found the government in disarray, the Foreign Ministry in chaos. Before anything could be decided, the Panther was at anchor in the Bay of Agadir. Cambon did not know what it would take to persuade the ship to sail away. He knew that negotiations must continue and that “serious colonial compensation”45 would have to be considered. But now it seemed that Kiderlen thought seriously of annexing part of southern Morocco. Kiderlen himself was unhelpful in determining the goal of German policy; the State Secretary now employed the same sphinx-like behavior as Bülow had in 1905. “The more silent we are,46 the more uncomfortable the French will become,” Kiderlen noted cheerfully.

Negotiations began on July 9 when the French Ambassador, icy and austere, called on Kiderlen. “Eh bien?”47 he said, inviting the State Secretary to explain reasons for the Panther’s leap. “Vous avez du neuf?” (“Do you have anything new?”) replied Kiderlen, tossing the ball back to his guest. Gradually, the shape of the negotiations began to emerge. The French government could not agree to acquisition of Moroccan territory by Germany because of French public opinion, but was ready to offer compensation elsewhere, perhaps in the French Congo. Kiderlen, certain of his negotiating advantage, observed that the hopes of the German public for a piece of Morocco had now been raised and could be satisfied only if the compensation elsewhere was substantial. He declared to a friend, “The German Government48 is in a splendid position. M. Cambon is wriggling before me like a worm.”

Although Kiderlen expected to deal directly—and only—with France, the Panther’s arrival in Agadir concerned other powers. Kiderlen, in calculating his move, had not given the reaction of other nations much thought. Russia, he sensed, would give only halfhearted support to her ally; St. Petersburg had never been anxious to fight a war over a French colony in Africa. England’s role in the matter Kiderlen had scarcely considered. Thus, when Sir Edward Grey called in Count Metternich on July 4 to discover Germany’s intentions, the Ambassador could not be helpful. He did not know himself; Kiderlen had not informed him. When Grey asked whether German troops would be landed, Metternich pleaded ignorance. Grey made the point that while Germany had taken an overt step by sending a ship, Britain “had not taken any overt step,49 though our commercial interests in Morocco were greater than those of Germany.” He left the Ambassador with the statement that Britain’s attitude toward what happened in Morocco “could not be a disinterested one”50 and reminded his guest of “our treaty obligations51 to France.”

Great Britain’s apprehension over the Panther’s appearance at Agadir arose from several sources. There was dislike for the suddenness and roughness of the German move; it smacked of the same shock tactics Bülow and Holstein had employed in the Kaiser’s sudden descent on Tangier. There was concern that Germany intended to acquire a naval station on Morocco’s Atlantic coast; this could threaten the Imperial sealanes to South Africa and around the Cape. (Careful analysts at the Admiralty and in the press discounted this danger, pointing out that a base at Agadir, 1,500 miles from the North Sea, would be highly vulnerable and ultimately a source of weakness rather than strength for the Imperial Navy. The First Sea Lord, Sir Arthur Wilson, assured Grey that neither Agadir or any other Moroccan site could quickly or easily be transformed into a fortified and formidable naval base.) Finally, Grey was concerned about France and the Entente. Once again, as at Tangier and Algeciras, Germany seemed intent on humiliating France, either by forcing a partition of Morocco or by stripping France of an embarrassingly large slice of French territory elsewhere. Such a loss of French prestige, while England stood by, would gravely damage the Entente. Grey was resolved that England should not merely stand by.

In the face of London’s concerns and Grey’s questions, Berlin remained silent. Asquith, speaking in Parliament on July 6, suggested that the government would welcome a statement of German intentions. Crowe, writing on July 17, asked himself: “What is Germany driving at?52 Herr von Kiderlen’s behavior seems almost inexplicable.” From Paris came reports that the French government was being squeezed to give up the entire French Congo; from Morocco, that German troops had landed at Agadir and that German officers were negotiating with tribal chiefs. Days passed and still Germany offered no explanation other than that endangered Germans were being protected. This passage of time added conspicuous insult to possible injury. Grey had stated in his July 4 conversation with Metternich that Great Britain had a vital interest in the future of France’s role in Morocco, yet for over two weeks, the Imperial government had ignored that concern. Officials at the Foreign Office, many considerably more Germanophobic than Grey, were alarmed and angry. “This is a test of strength,53 if anything,” Crowe argued. “Concession [by France] means not loss of interests or loss of prestige. It means defeat. The defeat of France is a matter vital to this country.” Sir Arthur Nicolson, who in 1910 had returned from St. Petersburg to become Permanent Under Secretary of the Foreign Office, agreed. Without a strong show of England’s support, he advised the Foreign Secretary, German pressure would soon compel France either to fight or to yield. If France yielded, he continued, German hegemony on the Continent would become permanent.

By July 19, Grey was convinced that he must have information as to German intentions. He asked Asquith to allow him to “make some communication54 to Germany to impress upon her that, if the negotiations between her and France come to nothing, we must become a party to a discussion of the situation.” Otherwise, he feared that the “long ignorance and silence55 combined must lead the Germans to imagine that we don’t very much care.” The Prime Minister agreed and Grey summoned Metternich to an interview on the afternoon of July 21.

From the British perspective, the twenty-first was the critical day of the Agadir Crisis. The Cabinet met in the morning, the Foreign Secretary saw the German Ambassador in the afternoon, and a historic speech was given in the evening. During the day, several conversations between leading members of the British government gave clear definition to British policy. The previous morning The Times had published an accurate but unauthorized story from Paris, describing Germany’s sweeping demands on France. British public opinion, previously dubious about France’s Morocco policy, had turned against the Germans. When the Cabinet met in the morning, Grey summarized the state of the Franco-German negotiations as reported to him by the French government. He pointed out that seventeen days had elapsed without any notice being taken by Germany of the British query about German intentions. He announced that he was seeing Metternich in the afternoon and would ask for clarification. Meeting the German Ambassador at four P.M., Grey explained that Britain had waited in hopes that France and Germany would reach agreement, but that he had heard that German demands were too excessive for France to accept. Meanwhile, the German presence continued at Agadir: no one knew “whether German troops are landed56 there, whether treaties were concluded there which injure the economic share of others,” whether, perhaps, the German flag had been raised. Metternich, as much in the dark on these matters as Grey, was, the Foreign Secretary minuted, “not in a position57 to give any information.”

Meanwhile during the day, another drama was unfolding in Whitehall. For weeks, David Lloyd George, the volatile, Germanophile Chancellor of the Exchequer, had been wrestling with the implications of the Panther’s leap. He wished to give Germany time to explain, yet the long silence from Berlin was ominous. That morning, before the Cabinet meeting, Winston Churchill visited him in his office. “I found a different man,”58 Churchill was to write. “His mind was made up. He saw quite clearly the course to take. He knew what to do and how and when to do it.... He told me that he was to address the Bankers at their Annual Dinner that evening and that he intended to make it clear that if Germany meant war, she would find Britain against her. He showed me what he had prepared and told me that he would show it to the Prime Minister and Sir Edward Grey after the Cabinet.” Lloyd George was irritated and concerned: “When the rude indifference59 of the German Government to our communication had lasted for seventeen days... I felt that matters were growing tensely critical and that we were drifting clumsily towards war,” the Chancellor wrote. “It was not merely that by failing even to send a formal acknowledgement of the Foreign Secretary’s letter, the Germans were treating us with intolerable insolence, but that their silence might well mean that they were blindly ignorant of the sense in which we treated our obligations under the Treaty [of 1904], and might not realise until too late that we felt bound to stand by France.”

Lloyd George did not speak up at the meeting of the Cabinet and thus, when Grey met Metternich, the Foreign Secretary was unaware of the new resolution found by his colleague. The Foreign Secretary learned about it only in the late afternoon when, he wrote, “I was suddenly told60 that Lloyd George had come over to the Foreign Office and wanted to see me. He came into my room and asked if the German Government had given any answer to the communication I had made on behalf of the Cabinet on July 4. I said that none had reached me.... Lloyd George then asked whether it was not unusual for our communication to be left without any notice and I replied that it was. He told me that he had to make a speech in the City of London that evening and thought he ought to say something about it; he then took a paper from his pocket and read out what he had put down as suitable. I thought what he proposed to say was quite justified and would be salutary, and I cordially agreed.... The speech was entirely Lloyd George’s own idea. I did nothing to instigate it, but I welcomed it.” On Grey’s recommendation, Asquith approved.

On the evening of July 21, Lloyd George arose before the assembled bankers of the City of London at the banquet given them at the Mansion House by the Lord Mayor.61 The bulk of his speech dealt with politics, the budget, inequities of property and wealth, and the prospects for world prosperity. Peace, he declared, was the “first condition of prosperity.” Then, halting the flow of extemporaneous words, he picked up a piece of paper and read slowly the carefully considered words he had showed to Grey and Asquith:

“I would make great sacrifices to preserve peace. I conceive that nothing would justify a disturbance of international good will except questions of the gravest national moment. But if a situation were to be forced upon us in which peace could only be preserved by the surrender of the great and beneficent position Britain has won by centuries of heroism and achievement, by allowing Britain to be treated, where her interests were vitally concerned, as if she were of no account in the Cabinet of nations, then I say emphatically that peace at that price would be a humiliation intolerable for a great country like ours to endure....”

The message was not remarkable: Britain, in matters affecting her interest, did not intend to be ignored. Sir Edward Grey had been passing this message to the diplomatic chancellories of Europe for six and a half years. What gave the Mansion House speech significance were the lips from which this message sprang. Lloyd George was a radical, a pacifist. His views on foreign affairs, insofar as they were known, were considered to be pro-German; certainly he had always strongly favored an Anglo-German understanding. The fact that he had stood up in public and warned that Britain would fight to maintain her prestige came as a shock to many in both England and Germany. During the furor that followed, Grey reckoned that the speech had a positive effect. “Lloyd George was closely associated62 with what was supposed to be a pro-German element in the Liberal Government and the House of Commons,” the Foreign Secretary wrote. “Therefore, when he spoke out, the Germans knew that the whole of the Government and House of Commons had to be reckoned with. It was my opinion then, and it is so still, that the speech had much to do with preserving peace in 1911. It created a great explosion of words in Germany, but it made the Chauvinists doubt whether it would be wise to fire the guns.”

Lloyd George’s speech had made no reference to any specific nation, but Germans recognized that the Chancellor’s warning was addressed to them. The German press quickly turned violent against England, protesting that here was yet another episode in the age-old story of Britain interfering in a question which did not concern her. Her real aim, declared Germania, was to make certain that she shared in any partition of Morocco: “Whenever a country occupies63 one village, England immediately demands three and preferably four.” Indignant cries mingled with blustering anger. “The German people refuse64 to be dictated to by foreign powers,” said the Kölnische Zeitung. “Strong in the justice of her cause, Germany admonishes the stupid disturbers of the peace, ‘Hands off!’”65 shouted the Lokal Anzeiger.

In the Wilhelmstrasse, Kiderlen was angry because the British Chancellor’s speech, by encouraging the French, could only make his negotiations with Paris more difficult. And the State Secretary was furious at what he considered a breach of diplomatic manners. The British Foreign Secretary had asked the German Ambassador for a clarification of the German position in Morocco. The Ambassador had promised to contact his government in an effort to provide what was asked. Yet that very same evening, before the Ambassador’s message could even be decoded in Berlin, a senior minister of the British government had issued a public warning to the Imperial government. Kiderlen assumed that the entire British Cabinet had drafted or at least approved Lloyd George’s speech and then chosen the leading pacifist and Germanophile among them as a mouthpiece to increase the harshness of the insult. Kiderlen seethed: “If the English Government had intended66 to complicate the political situation and to bring about a violent explosion, it could certainly have chosen no better means than the speech of the Chancellor of the Exchequer.”

Kiderlen had to do something. If he ignored the speech completely, France might decide that it had England’s backing and break off negotiations. And if he ignored Grey’s request to Metternich, the unpredictable English might encourage France to defy the German Empire. Britain had to be mollified in a way that did not seem a response to the Mansion House speech or to any other form of British pressure; nationalist opinion in Germany would never forgive that. Kiderlen decided to approach Grey confidentially and explain German objectives in Morocco.

On Monday, July 24, Metternich asked to see Grey, saying that he brought news from Berlin. The Ambassador began by announcing that the Panther had been sent “to protect German interests67... the special cause was the attack of natives on a German farm.” Grey took him up on this point: “I observed that I had not,68 I thought, heard of this attack before. I had understood that the dispatch of the ship had been due to apprehension as to what might happen, not to what had actually happened.” Count Metternich admitted that he had not heard of the actual attack before, either. “I observed that there were no Germans69 in this region,” Grey continued. “Count Metternich said he had no information on this point.” The Ambassador assured the Foreign Secretary, however, that “not a man had been landed”70 and that no troops would be landed. Further, Metternich continued, “Germany had never thought of creating a naval base on the Moroccan coast and never would think of it.” Germany had no intention of taking any Moroccan territory. All she asked was compensation for France’s breach of the Act of Algeciras. Grey was satisfied and asked whether he could communicate what Metternich had told him to the House of Commons. Metternich said that he would ask permission from Berlin.

Grey’s request, relayed by Metternich, made Kiderlen even angrier. The next day, Tuesday, July 25, the German Ambassador returned to see Grey with the answer from Berlin: Kiderlen would not permit the Foreign Secretary to announce in Parliament what he had been told in confidence. The reason was Lloyd George’s speech. “That speech had been interpreted71 without contradiction as having a tone of provocation for Germany and the German Government could not let the belief arise that, in consequence of the speech, they had made a declaration of intentions about Morocco”—this was how Grey reported his interview with Metternich. As to German negotiations with France: “If, after the many provocations72 from the side of France and her free-and-easy manner in Morocco, as if neither Germany nor a treaty existed, France should repel the hand that was offered to her by Germany, German dignity as a Great Power would make it necessary to secure by all means, and if necessary also, alone, full respect by France of German treaty rights.” Grey, angered by the barely concealed charge that he had conspired with his Cabinet colleagues to impugn German national honor, drew himself up to defend the dignity of the British government. Since the Germans “had said that it was not consistent73 with their dignity, after the speech of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, to give explanations as to what was taking place at Agadir,” Grey declared that it was “not consistent with our dignity to give explanations as to the speech of the Chancellor of the Exchequer.” The gunboat at Agadir, German intentions in Morocco, the Franco-German negotiations—all had now been subordinated to an affair of national prestige. The air was filled with tension; many—Lloyd George among them—thought that war was near.

That same afternoon, about five-thirty P.M., Lloyd George and Churchill “were walking by the fountains74 of Buckingham Palace,” as Churchill recalled. Running after them came a messenger, asking that the Chancellor go immediately to see Sir Edward Grey. Churchill went too and together they found the Foreign Secretary in his rooms at the House of Commons. Grey, who had just walked over from the Foreign Office after his interview with Metternich, was pale. “I have just received a communication75 from the German ambassador so stiff that the Fleet might be attacked at any moment. I have sent for McKenna to warn him,” the Foreign Secretary told his colleagues. While they were speaking, the First Lord came in, listened for a few minutes, and then hurried away to send orders to the Fleet.

Grey was alarmed; already that day he had sent a note to McKenna emphasizing that “we are dealing with a people76 who recognize no law except that of force between nations and whose fleet is mobilized at the present moment.” Four days before, on the twenty-first, The Times had announced that the German High Seas Fleet of sixteen battleships and four armored cruisers had put to sea and “vanished into the desolate wastes77 of the North Sea.”fn2 Grey’s warning to McKenna resulted in a general alert to the British Fleet. There were rumors, following the Times story, that the Germans might attempt “a bolt from the blue” against the Royal Navy. “Supposing the High Seas Fleet,80 instead of going to Norway as announced, had gone straight for Portland, preceded by a division of destroyers, and, after a surprise night torpedo attack, had brought the main [German] fleet into action at dawn against our ships without steam, without coal, without crews...”

The First Sea Lord, Sir Arthur Wilson, evidently thought little of this alarm and left on July 21 for a weekend of shooting in Scotland. Winston Churchill found this shocking. “Practically everybody of importance81 and authority is away on holiday,” he complained to Lloyd George. As Home Secretary, Churchill had no responsibilities in the Agadir Crisis except a general one as a member of the Cabinet. Nevertheless, his blood was up. When, at the peak of the crisis, he learned that the navy’s reserves of gunpowder were unprotected, he plunged into action:

“On the afternoon of July 27,82 I attended a party at 10 Downing Street. There I met the Chief Commissioner of Police.... He remarked that by an odd arrangement, the Home Office [which was Churchill’s responsibility] was responsible, through the Metropolitan Police, for guarding the magazines... in which all the reserves of naval cordite were stored. For many years these magazines had been protected without misadventure by a few constables. I asked what would happen if twenty determined Germans in two or three motor cars arrived well armed upon the scene one night. He said they would be able to do what they liked. I quitted the garden party.

“A few minutes later I was telephoning from my room in Home Office to the Admiralty. Who was in charge?... An Admiral (he shall be nameless) was in control. I demanded Marines at once to guard these magazines, vital to the Royal Navy.... The admiral replied over the telephone that the Admiralty had no responsibility and no intention of assuming any; and it was clear from his manner that he resented the intrusion of an alarmist civilian Minister. ‘You refuse, then, to send the Marines?’ After some hesitation he replied, ‘I refuse.’ I replaced the receiver and rang up the War Office. Mr. Haldane was there. I told him that I was reinforcing and arming the police that night and asked for a company of infantry for each magazine in addition. In a few minutes the orders were given; in a few hours the troops had moved. By the next day, the cordite reserves of the Navy were safe.”

Kiderlen was unaware of the movements of the British Fleet, but he knew from Lloyd George’s speech and from Metternich’s reports of his interviews with Grey that England was in earnest about France and Morocco. These manifestations of English “meddling” in German affairs may have been much resented in Germany, but they helped to focus the Wilhelmstrasse on the reality of the situation: if France was pushed into war by German pressure, England would fight beside its Entente partner. German objectives in Morocco or elsewhere in Africa were not worth a war with France, England, and probably Russia as well. Once Kiderlen grasped this, he began to moderate his demands, look for compromise, and speak in conciliatory terms.

On July 26, Metternich received new instructions from Berlin, and on Thursday, the twenty-seventh, he again called on Grey at the Foreign Office. This time, Grey said, the atmosphere was “exceedingly friendly.”83 The German government had reversed its earlier position. Now, Metternich asked that Parliament be told that, while the Franco-German negotiations would remain exclusively Franco-German, they would not touch on British interests. Any territories exchanged would be exclusively French or German, although Metternich requested that Grey not give M.P.’s any details. Further, the Ambassador said, if the British government could make a public statement saying that it would be pleased by a successful conclusion of the negotiations, this would have a beneficial influence. He meant, on France.

This information was passed along in the House of Commons that afternoon, not by the Foreign Secretary, but by the Prime Minister. Asquith said: “Conversations are proceeding84 between France and Germany; we are not a party to those conversations; the subject matter of them may not affect British interests. On that point, until we know the ultimate result, we cannot express a final opinion. But it is our desire that those conversations should issue in a settlement honorable and satisfactory to both parties and of which His Majesty’s Government can cordially say that it in no way prejudices British interests. We believe that to be possible. We earnestly and sincerely desire to see it accomplished. The Question of Morocco itself bristles with difficulties, but outside Morocco, in other parts of West Africa, we should not think of attempting to interfere with territorial arrangements considered reasonable by those who are more directly interested. Any statements that we have interfered to prejudice negotiations between France and Germany are mischievous inventions without the faintest foundation in fact. But we have thought it right from the beginning to make it quite clear that, failing such a settlement as I have indicated, we must become an active party in discussion of the situation. That would be our right as a signatory of the treaty of Algeciras, it might be our obligation under the terms of our agreement of 1904 with France; it might be our duty in defence of British interests directly affected by further developments.”

The Anglo-German phase of the crisis was over. The moderate German press was vastly relieved. “Peace or war85 hung upon Herr Asquith’s words,” wrote the Vossische Zeitung the following day. “His was perhaps the gravest responsibility of any statesman in recent years. It was a peaceful speech.” The Franco-German dispute was not resolved. But the speeches of Lloyd George and Asquith and the conversations between Grey and Metternich clearly established in the minds of both French and German negotiators that Britain hoped for a successful outcome to the talks and that Britain advised reasonable concessions by France to square its increased role in Morocco. But it was also established that where France dug in against what she considered excessive German demands, Britain stood by her side.

From that point until the Agadir Crisis was finally resolved in mid-October, negotiations were exclusively Franco-German, conducted in Berlin between Kiderlen and the French Ambassador, Jules Cambon. Britain’s warning on Morocco had hedged German ambitions, but Kiderlen’s policy had to produce some fruit. The talks turned to compensation and Kiderlen demanded the entire French Congo. The French refused to surrender an entire colony; the government would not survive. France, feeling the presence of Britain behind her, became defiant. Pierre Messimy, the War Minister, announced that “we are not going to stand86 any more nonsense from Berlin... and we have the nation behind us.” There was talk of sending a French cruiser to Agadir. Both governments, in fact, found themselves tormented by the fierceness of their own public opinion. Grey observed from London: “The Germans at first87 made such huge demands on the French Congo as it was obvious that no French Government could concede,” he wrote later. “The fact was that both Governments had got into a very difficult position; each was afraid of its own public opinion. The German Government dared not accept little. Their own Colonial Party had got their feelings excited and their mouth very wide open. If the mouth was not filled—and it would need a big slice to fill it—there would be great shouting. The French Colonial Party would revolt if their Government gave up too much. Probably after a time the German Government was as anxious as the French Government to get out of the business by a settlement, but neither dared settle.”

Kiderlen was trapped between France’s refusal to grant the sweeping compensation which would mask his failure in Morocco, and the vehement cries of German nationalists. Most German nationalists had little interest in the steamy equatorial forests of the Congo, “where the fever bacillus and the sand flea88 say good night to each other” and where the “only prospect of of profitable traffic [lay] in sand for our breeders of canaries.” They still wanted a piece of Morocco, and as they sensed this possibility ebbing away they trumpeted their impatience and frustration. “Has the spirit of Prussia perished?”89 demanded the Post. “Have we become a generation of old women? What has become of the Hohenzollerns?” France’s seizure of Morocco was said to be a military threat to the Reich; the French would use native soldiers to fill out the gaps in the French Army caused by a declining birthrate. (A German cartoon displayed a ragged file of apes and monkeys dressed in French uniforms parading past a French officer. The caption read: “The last class of reserves.”90) General Moltke, the Chief of the General Staff, was indignant. “If we slink out91 of this affair with our tails between our legs, and if we do not make a demand which we are prepared to enforce with the sword, I despair of the Empire’s future,” he growled.

The Kaiser was skittish. As the crisis with England mounted, William—fearing war with Great Britain—nervously telephoned Kiderlen and Bethmann to report to him at Swinemünde. William complained that Kiderlen was going beyond the limits agreed on board the Hohenzollern. Kiderlen replied by drafting a letter of resignation. France, he insisted, would make a major offer only if she was convinced that Germany was serious. “I do not believe92 that they would take up the challenge but they must feel that we are ready for everything.” If that policy was unacceptable to his sovereign, he would resign. Bethmann had gone this far with Kiderlen and decided that he had to continue. If the State Secretary was allowed to resign, he said, he would submit his own resignation. William gave in. “The Kaiser was very humble93 in Swinemunde. Kiderlen returned very pleased,” said Kurt Riezler, the Chancellor’s personal assistant. But Bethmann, finding himself with almost no voice, was thoroughly unhappy. “Kiderlen informs nobody,94 not even the Chancellor,” reported Riezler. “Bethmann said yesterday he wanted to give Kiderlen a lot to drink in the evening in order to find out what he ultimately wants.” Meanwhile, William, stung by the contempt of the nationalist press, reverted to bombast. “I am not going to dance attendance95 on the French any longer,” he declared on August 7. “They must make an acceptable offer at once or we will take more, and that immediately.” On August 13, he spoke of using his sword. “We will insist96 upon our demands, for it is an affair of honor for Germany.” Unless the French gave Kiderlen whatever the State Secretary asked, William announced, he would “not be satisfied97 until the last Frenchman was driven out of Morocco—by the sword if necessary.”

By August 16, Kiderlen and Cambon together announced that the situation was “grave.” Six French offers of territorial concession in the Congo had been rejected by Germany, and seven German proposals had been rejected by France. On the eighteenth, the talks in Berlin were suspended. Cambon went to Paris for further instructions. Kiderlen, inexplicably, departed on vacation for Chamonix in the French Alps. Frau Krypke accompanied him; they were met by the local French prefect, who had instructions from M. Caillaux to make the German couple as comfortable as possible. Apparently, Kiderlen had suspended the negotiations in the hope that the rising tension would compel the French to give in. In fact, the passage of time worked against the State Secretary. Cambon returned from Paris at the end of August, instructed to secure definite German acquiescence to a French protectorate in Morocco before he agreed to any further discussions of compensation to be paid in the Congo. With the French standing firm, Kiderlen’s confidence began to falter. Commercial barons such as Ballin, who had cheered the Panther’s spring in the beginning, did not approve Kiderlen’s demand for the entire French Congo with the consequent rumors of war. Nine weeks of fruitless bargaining had filled the air with suspense and exhausted the public patience. The Kaiser was impatient and fidgety. “What the devil will happen98 now?” he asked. “It is pure farce. They negotiate and negotiate and nothing happens.”

The resumption of talks between the French Ambassador and the German Foreign Minister was scheduled for Friday, September 1. It was postponed with no reason given. Cambon was slightly ill, but Kiderlen failed to pass this news to the press. The result was a panic on the Berlin stock market on the morning of September 2. Although the talks began on Monday, September 4, there were runs on banks as nervous depositors withdrew their capital. Waves of selling orders came in from the provinces, and the day was known as Black Monday. During the week, the market rallied, then plunged again on Saturday the ninth. This was too much for Ballin, who told his friends that, thanks to Kiderlen, Germany was cornered: she would either have to go to war over an African swamp or back down and appear ridiculous. Under pressure from all sides, the State Secretary began to retreat. He agreed to recognize a de facto French protectorate in Morocco provided the word “protectorate” itself did not appear on paper. On October 11, a draft of the Morocco Convention was initialed by Kiderlen and Cambon. In return for her political protectorate (the term was not used), France pledged to safeguard for thirty years the principle of the Open Door in Morocco. By the twenty-second, the sacrifices France was to make in compensation had been agreed: 100,000 square miles of territory in the French Congo were ceded and added to the German colony of Cameroons. On November 4, the final Franco-German agreement was signed in Berlin. In over a hundred meetings, Kiderlen and Cambon had developed affection for each other. They exchanged photographs inscribed “A mon terrible ami”99 and “A mon amiable ennemi.”

The result was a triumph for France and a defeat for Germany. Sir Edward Grey called it “almost a fiasco for Germany;100 out of this mountain of a German-made crisis came a mouse of colonial territory in Africa.” Kiderlen had taken great risks, had made a massive display of diplomatic force, and had achieved nothing in Morocco: no slice of territory, no naval base on the Atlantic, no retreat of the French from Fez. Even in the Congo, he had finally accepted less than half the territory he had earlier fixed as an irreducible minimum. For this he had provoked a prolonged international crisis, called the world’s attention to Britain’s support of France, and raised the French Republic to a level of prestige the country had not enjoyed since the Second Empire.

There was no way to mask these facts, and the air in Berlin filled with anger and recrimination. The nationalist press roared that the settlement was “the last nail101 in the coffin of German prestige.” Harden complained, “Without acquiring anything102 of moment, we are more unpopular than ever.” Friedrich von Lindequist, the German Colonial Secretary, resigned, declaring that he could not defend the agreement before the Reichstag. Bülow called the episode “deplorable...103 a fiasco... like a damp squid, it startled, then amused, and ended by making us look ridiculous.” According to Bülow, Kiderlen himself blamed the disaster solely on William II, who “throughout this whole diplomatic campaign104 veered from absurd threats and demands to utter discouragement and pessimism leading to unnecessary concessions.”

Responsibility for the Panther’s spring had been Kiderlen’s, but it was Bethmann who rose to defend the Franco-German agreement in the Reichstag. He pointed out that the government had achieved “a considerable increase105 of Germany’s colonial domain” without giving up anything in Morocco that Germany had ever had and that “an important dispute with France106 had been settled peacefully.” “We drew up a program and we carried it out,” he declared—and the chamber burst into laughter and derisive shouts. When the Chancellor concluded, “We expect no praise107 but we fear no reproach,” the atmosphere changed, but not for the better. “The silence,” reported the Berliner Tageblatt, “was like that of the grave.108 Not a hand moved, no applause rang out.” The reply to the Chancellor, primarily from the nationalists, but in which all parties participated, was savage. Ernst Basserman, the National Liberal leader, wanted to know why military pressure had not been exerted on France in the Vosges, where the German Army was powerful, rather than at Agadir by a mere gunboat. Ernst von Heyderbrand, the Conservative leader, complained loudly of the decline of German prestige and pointed the finger of blame at England:

“Like a flash in the night,109 all this has shown the German people where the enemy is. We know now, when we wish to expand in the world, when we wish to have our place in the sun, who it is that lays claim to world-wide domination.... Gentlemen, we Germans are not in the habit of permitting this sort of thing and the German people will know how to reply.... We shall secure peace, not by concessions, but with the German sword.”

Heyerbrand’s speech was punctuated by hearty, ostentatious applause from the royal box, where the Crown Prince was sitting with one of his younger brothers. Bethmann was infuriated by this expression of partisan, antigovernment sentiment and demanded of the Kaiser that he discipline his Heir. William obliged. Summoning both his son and his Chancellor, he allowed Bethmann to remonstrate with the Crown Prince and explain in detail the position of the Imperial government. Afterward, Bethmann was content with his own role. “My conscience lets me sleep,”110 he said. “War for the Sultan of Morocco, for a piece of the Congo or for the Brothers Mannesmann would have been a crime.”... “If I had driven toward war,111 we would now stand somewhere in France, our fleet would largely lie at the bottom of the North Sea, Hamburg and Bremen would be blockaded or bombarded, and the entire nation would ask me, Why this?... And it would rightly string me up on the nearest tree.” About this time, when his friend Sir Edward Goschen, the British Ambassador, asked whether he still had time to play his usual Beethoven sonata before going to bed, Bethmann replied, “My dear friend,112 you and I like classical music with its plain and straightforward harmonies. How can I play my beloved old melodies with the air full of modern discord?”

For Kiderlen, the debacle was personal. In January 1912, less than two months after signing the convention with Cambon, Kiderlen appeared in Rome, where Bülow was living. “I thought he looked ill,”113 Bülow observed. “His face had a worn and puffy look and certainly he drank far too heavily.” Bülow cautioned him to slow down, but Kiderlen replied that he would not last long in any case. His influence in the government had eroded almost to nothing; when Haldane, the British Minister of War, came to Berlin to discuss Anglo-German relations, the German Foreign Minister was excluded from most of the negotiations. On December 30, 1912, one year after his humiliation, Kiderlen, home for Christmas in his native Stuttgart, drank six glasses of cognac after dinner, collapsed, and died of a heart attack.

fn1 211 feet long, 32 feet in beam, one 4-inch gun forward, one aft.

fn2 In fact, the Admiralty had been aware of the plans and the destination of the German Fleet. Indeed, the British Atlantic Fleet under Sir John Jellicoe was at Rosyth, on the Firth of Forth, preparing to sail for joint exercises with the German High Seas Fleet in Norwegian waters. Sailors on both sides had been looking forward to the maneuvers as a chance both to renew old acquaintances and to scout the tactics and equipment of a potential foe. But neither Whitehall or the Wilhelmstrasse wished the fleets to meet in a time of tension such as this. “At the end of three days,”78 Kiderlen had said to Goschen on June 14, “they might either fraternize too much... or they might on the contrary be shaking their fists in each other’s faces.” The Kaiser also was cruising in Norwegian waters, on board the Hohenzollern, and the prospect of him becoming involved worried Kiderlen almost as much. “You know the Emperor pretty well,”79 he said to Goschen, “and you can imagine how excited he will be at the sight of the two Squadrons. He will certainly want to make the most of the opportunity and there is every chance that, as an Admiral of both Navies, he will amuse himself by putting himself at the head of the combined squadron and going through a series of naval maneuvers—ending with a great banquet, toasts, and God knows what!”