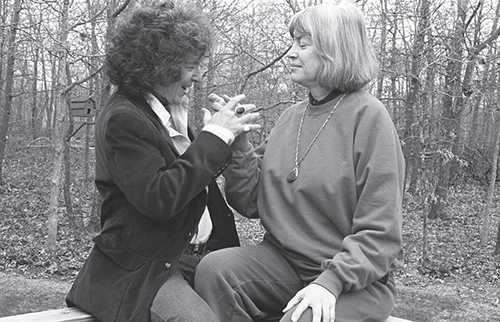

photo © Margaret Randall

“Never go anywhere without your gang!”

—BLANCHE WIESEN COOK, historian, author, and professor of history

It was a clear, starlit evening in July 2019 when I walked to the New York Historical Society on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, located directly across from Central Park. I was looking forward to attending the sold-out event, “Coconspirators: An Evening with Blanche Wiesen Cook and Clare Coss.” Blanche is a historian, professor, and author of numerous books, including a three-volume biography of Eleanor Roosevelt. Clare, psychotherapist emeritus, is a librettist and award-winning playwright. They first met in 1966 at a meeting of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom called to organize an action against the war in Vietnam.

As I entered the museum and found my way to the room where the discussion was being held, I noticed a large rectangular cake sitting on a table just outside the entrance door. In colorful lettering on white frosting, it read: Happy 50th Anniversary. Blanche and Clare had been partners in life for fifty years.

For the next ninety minutes, the audience listened intently. Blanche first spoke about the women who inspired her. “Our gang in the seventies was amazing,” she said. That gang included renowned poet, essayist, and feminist Adrienne Rich and civil rights activist and poet Audre Lorde, whose awe-inspiring quotes include, “Your silence will not protect you.” Blanche recalled, “They were both my guides at the time. We were all in it together, protesting to end the Vietnam War. It was an electrifying time.”

Clare talked about two women who inspired her commitment to activism and equal justice. First was Lillian Wald, founder of the Henry Street Settlement and the Visiting Nurse Service in 1893, and the Neighborhood Playhouse in 1916—all three vibrant New York institutions to this day. “Wald’s vision and activism to work for international peace and to bring education, sanitation, playgrounds, health care, school lunches, and the arts to the Lower East Side served as a model for the country,” she said. In her research on Wald, she discovered another inspiration, Mary White Ovington, cofounder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. “She was the first white woman in the early 1900s to dedicate her life to racial justice.”

They also recognize and appreciate how they have inspired each other over the decades. “Clare is the leader of my personal gang,” Blanche said. “Her brilliance inspires and informs all my work.”

“Blanche is bold and unafraid of confrontation or disagreement and always speaks truth to power. She taught me a lot on that score,” Clare responded.

I was touched by this conversation, seeing their dedication to their causes as well as to each other. And interviewing them in their home two months later only reinforced their authentic commitment to their work and to one another.

Clare greeted me at the door as soon as I arrived. It was October, and she was dressed for fall in black and gray. Her white hair hung softly just above her shoulders, framing her bangs which stop just above her small, round, unframed eyeglasses. Their home is filled with books and memorabilia, particularly photos of Eleanor Roosevelt. “I call her ‘the other woman,’” Clare said with a wide grin. After I followed Clare into the living room, Blanche entered, and we sat to talk. Blanche has salt-and-pepper, short curly hair, and she was clothed in western wear: blue jeans and red cowgirl boots. Blanche and Clare immediately held hands. Blanche is seventy-eight years old, and Clare recently turned eighty-four.

On a full moon in June 2019, their chosen anniversary month, they celebrated their fiftieth year together. On their fortieth anniversary, they “eloped” to Martha’s Vineyard for a small private wedding on a friend’s deck overlooking the bay. Gay marriage had just become legal in Massachusetts. “July 11 is the tenth anniversary of our marriage,” Clare said.

“We were each married to men when we met. After three years of courtship, shared activism, and intense passion, we left our husbands to live together,” Blanche shared.

As an activist and playwright, Clare believes we all “have the power to create a just world,” and has written one-woman plays about her mentors: Lillian Wald and Mary White Ovington. “Their steady, embracing, and fierce commitment to justice deepened and informed my own activism,” Clare said. In October 2020, the new opera, Emmett Till, which composer Mary Watkins set to Clare’s libretto, will premiere at John Jay College’s Gerald W Lynch Theater. Presented in association with John Jay, Opera Noire of NY, and The Harlem Chamber Players, the libretto narrates the horrific murder of a fourteen-year-old African American Chicago boy, Emmett Till, who was kidnapped, tortured, and murdered in the Mississippi Delta in 1955 for allegedly wolf-whistling at a white woman. Mamie Till-Mobley insisted on an open casket so the world could see what happened to her son, and courageously testified at the trial under death threats. Photos of this image appeared in hundreds of magazines and newspapers around the country and the world, placing a spotlight on his tragic death and the racism that caused it. Roanne Taylor, the teacher (a character Clare introduces), represents white folks who care but remain silent. Her dramatic arc travels from denial to the recognition of responsibility. “Mary Watkins and I have collaborated through five years of development workshops and sing-throughs,” Clare said. “My play, Emmett Down in My Heart, which inspired the opera, will have a production in German by an Afro-German theater troupe, Label Noir, in December 2020 in Berlin.”

At that point Clare graciously turned toward her partner, and Blanche talked about her work. Blanche has fought for women’s rights, sexual freedom, and peace. As cofounder of the Freedom of Information and Accountability Committee (FOIA), she kept the Freedom of Information Act alive and fought to keep government records publicly accessible. “When I was working on my book, The Declassified Eisenhower, everything I wanted was classified,” she said. “I asked for papers about Iran and Guatemala, and everything was secret. When the library trays were wheeled to me, they were all empty.” That’s what led to her founding FOIA, which provides the public with the right to receive any records requested from federal agencies. “I flew out of Abilene to New York to call a meeting of historians, journalists, attorneys—members of the Center for Constitutional Rights and American Civil Liberties Union. We founded FOIA, Inc. Bella Abzug was in Congress, and she worked to get a Freedom of Information Act passed which guaranteed the public’s right to know—which remains embattled to this day.” Blanche’s book The Declassified Eisenhower was published in 1981. Ronald Reagan sought to reclassify many of the documents that we got declassified, and the battle against secrecy has intensified.”

While conducting research for her biographies of Eleanor Roosevelt, she was shocked to find that Eleanor’s FBI file was so large. “Over five thousand pages,” Blanche said, seemingly still in disbelief over this fact. “Eighty percent of her file is about her battles against lynching and racist terror. And J. Edgar Hoover hated her. He called her a ‘fat cow.’” She continued though she seemed ruffled now, as Eleanor Roosevelt is clearly her biggest hero and inspiration. “Hoover was a monster. He considered anyone who fought for peace and wanted to end poverty communists. He even called Jane Addams, who fought for women’s suffrage and advocated for world peace, the most dangerous woman in America in the year of her death, 1935.”

The more Blanche researched Eleanor Roosevelt, the more she discovered what a visionary she was, a woman who led with her heart. “Her great vision was her love for all people and her ability to empathize and communicate with everyone,” Blanche told me.

“We need more of that today,” Clare concurred. I noticed that the two of them were still holding hands, and was touched by their clear affection. “We both are dedicated to help make the world a better place.” She then referred to a quote by Annette T. Rubinstein, the renowned educator, author, and activist who passed at the age of ninety-seven in 2007. “Life is about the struggle.” Blanche nodded in agreement. “We feel a mandate to try to work for justice, gender equality, dignity, and respect for everyone,” Blanche added. “Our relationship keeps refueling us.”

Blanche turned the conversation to the present challenges we face. “It is so terrible all over the world. During the 1960s we hoped money would be transferred from military spending to addressing people’s needs. The SALT agreements, developed to restrain the arms race and limit nuclear weapons, were even signed by the USA and the USSR in the early 1970s. But now these agreements have been abandoned.”

Clare added, “The only way to keep from getting depressed is to keep active. Write a letter. Make a phone call. Sign a petition. Call a meeting. Organize. Demonstrate out on the streets. Do whatever you’re capable of doing. That’s why we write. I am drawn to characters in my writing who break the silence and act.

Clare asks herself, “What would Lillian Wald do? What would Mary White Ovington do? What would Eleanor do? Hey—what would Blanche do?” Blanche added, “What would Clare do?”