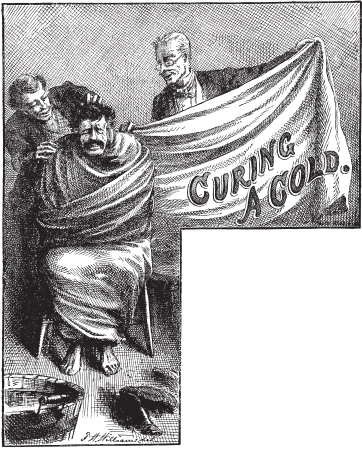

from Sketches New and Old (1875)

There’s nothing like being ill to make you sick . . . of doctors, medicine, and, of course, the most notorious of all symptoms: free advice from an army of interns practicing without a license.

The Autocrat of Russia possesses more power than any other man in the earth; but he cannot stop a sneeze.

—Following the Equator (1897)

Tom lay thinking. Presently it occurred to him that he wished he was sick; then he could stay home from school. Here was a vague possibility. He canvassed his system. No ailment was found, and he investigated again. This time he thought he could detect colicky symptoms, and he began to encourage them with considerable hope.

—The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876)

One should not bring sympathy to a sick man. It is always kindly meant, and of course it has to be taken—but it isn’t much of an improvement on castor oil. One who has a sick man’s true interest at heart will forbear spoken sympathy, and bring him surreptitious soup and fried oysters and other trifles that the doctor has tabooed.

—Letter to friend and early mentor Mary Mason Fairbanks

As far as being on the verge of being a sick man I don’t take any stock in that. I have been on the verge of being an angel all of my life, but it’s never happened yet.

—quoted in Mark Twain: A Biography (1912)

by Albert Bigelow Paine

Medicine has its office, it does its share and does it well; but without hope back of it, its forces are crippled and only the physician’s verdict can create that hope when the facts refuse to create it.

—Letter to Dr. W.W. Baldwin (1903 or ’04)

Any mummery will cure, if the patient’s faith is strong in it.

—A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889)

Man seems to be a rickety poor sort of a thing, any way you take him; a kind of British Museum of infirmities and inferiorities. He is always undergoing repairs. A machine that was as unreliable as he is would have no market.

—“The Lowest Animal” (1896)

Man starts in as a child and lives on diseases to the end as a regular diet.

—quoted in Mark Twain: A Biography (1912)

by Albert Bigelow Paine

Most cursed of all are the dentists who made too many parenthetical remarks—dentists who secure your instant and breathless interest in a tooth by taking a grip on it, and then stand there and drawl through a tedious anecdote before they give the dreaded jerk. Parentheses in literature and dentistry are in bad taste.

—A Tramp Abroad (1880)

The physicians think they are moved by regard for the best interest of the public. Isn’t there a little touch of self-interest back of it all? It seems to me there, and I don’t claim to have all the virtues—only nine or ten of them.

—1901 speech

All dentists talk while they work. They have inherited this from their professional ancestors, the barbers.

—Europe and Elsewhere (1923)

The Emperor commanded the physicians of greatest renown to appear before him for consultation . . . were they proper healers or merely assassins? Then the principal assassin, who was also the oldest doctor in the land and the most venerable in appearance, answered and said . . . “Sometimes they seem to help nature a little—a very little—but, as a rule, they merely do damage.”

—“Two Little Tales” (1901)

Whose property is my body? Probably mine. I so regard it. If I experiment with it, who must be answerable? I, not the State. If I choose injudiciously, does the State die? Oh, no.

—1901 speech

Dear Sir (or Madam):—I try every remedy sent to me. I am now on No. 67. Yours is 2,653. I am looking forward to its beneficial results.

—quoted in My Father, Mark Twain (1931)

by Clara Clemens

The first time I began to sneeze, a friend told me to go and bathe my feet in hot water and go to bed. I did so. Shortly afterward, another friend advised me to get up and take a cold shower-bath. I did that also. Within the hour, another friend assured me that it was policy to “feed a cold and starve a fever.” I had both. So I thought it best to fill myself up for the cold, and then keep dark and let the fever starve awhile . . .

I started down toward the office, and on the way encountered another bosom friend, who told me that a quart of salt-water, taken warm, would come as near curing a cold as anything in the world. I hardly thought I had room for it, but I tried it anyhow. The result was surprising. I believed I had thrown up my immortal soul . . . If I had another cold in the head, and there were no course left me but to take either an earthquake or a quart of warm saltwater, I would take my chances on the earthquake . . . I came across a lady who had just arrived from over the plains, and who said she had lived in a part of the country where doctors were scarce, and had from necessity acquired considerable skill in the treatment of simple “family complaints.” I knew she must have had much experience, for she appeared to be a hundred and fifty years old.

She mixed a decoction composed of molasses, aquafortis, turpentine, and various other drugs, and instructed me to take a wine-glass full of it every fifteen minutes. I never took but one dose; that was enough; it robbed me of all moral principle, and awoke every unworthy impulse of my nature.

I finally concluded to visit San Francisco, and the first day I got there a lady at the hotel told me to drink a quart of whiskey every twenty-four hours, and a friend up-town recommended precisely the same course. Each advised me to take a quart; that made half a gallon. I did it, and still live.

Now, with the kindest motives in the world, I offer for the consideration of consumptive patients the variegated course of treatment I have lately gone through. Let them try it; if it don’t cure, it can’t more than kill them.

—Sketches New and Old (1875)

Since I was seven years old I have seldom taken a dose of medicine, and have still seldomer needed one. But up to seven I lived exclusively on allopathic medicines. Not that I needed them, for I don’t think I did; it was for economy; my father took a drug store for a debt, and it made cod-liver cheaper than the other breakfast foods. We had nine barrels of it, and it lasted me seven years. Then I was weaned. The rest of the family had to get along with rhubarb and ipecac and such things, because I was the pet. I was the first Standard Oil trust. By the time the drug store was exhausted my health was established and there has never been much the matter with me since.

—1905 speech

By some happy fortune I was not seasick. That was a thing to be proud of. I had not always escaped before. If there is one thing in the world that will make a man peculiarly and insufferably self-conceited, it is to have his stomach behave itself, the first day at sea, when nearly all his comrades are seasick.

—The Innocents Abroad (1869)

I was always told that I was a sickly and precarious and tiresome and uncertain child, and lived mainly on allopathic medicines during the first seven years of my life. I asked my mother about this, in her old age—she was in her eighty-eighth year—and said:

“I suppose that during all that time you were uneasy about me?”

“Yes, the whole time.”

“Afraid I wouldn’t live?”

After a reflective pause—ostensibly to think out the facts—“No—afraid you would.”

—Autobiography

Do not undervalue the headache. While at its sharpest it seems a bad investment; but when relief begins, the unexpired remainder is worth four dollars a minute.

—Following the Equator (1897)

The only way to keep your health is to eat what you don’t want, drink what you don’t like, and do what you’d druther not.

—Following the Equator (1897)

I can quit any of nineteen injurious habits at any time, and without discomfort or inconvenience . . . after a few hours the desire is discouraged and comes no more. Once I tried my scheme in a large medical way. I had been confined to my bed several days with lumbago. My case refused to improve. Finally the doctor said: “My remedies have no fair chance. Consider what they have to fight, besides the lumbago. You smoke extravagantly, don’t you?’

“Yes.”

“You take coffee immoderately?”

“Yes.”

“You eat all kinds of things that are dissatisfied with each other’s company?”

“Yes.”

“You drink two hot Scotches every night?”

“Yes.”

“Very well, there you can see what I have to contend with. We can’t make any progress the way the matter stands. You must make a reduction in these things.”

“I can’t, doctor.”

“I lack the will-power. I can cut them off entirely, but I can’t moderate them.”

He said that would answer . . . I cut off all those things for two days and two nights . . . and at the end of forty-eight hours the lumbago was discouraged and left me. I was a well man; so I gave thanks and took to these delicacies again.

It seemed a valuable medical course, and I recommended it to a lady. She had run down and down and down, and had at last reached a point where medicines no longer had any helpful effect upon her. I said I knew I could put her upon her feet in a week. It brightened her up . . . So I said she must stop swearing and drinking and smoking and eating for four days, and then she would be all right again . . . but she said she could not stop swearing and smoking and drinking, because she had never done these things. So there it was. She had neglected her habits . . . She was a sinking vessel, with no freight to throw overboard . . . Why, even one or two little bad habits could have saved her, but she was just a moral pauper.

—Following the Equator (1897)

There was a good deal of cholera around the Mississippi Valley in those days, and my mother used to dose us children with a medicine called Patterson’s Patent Pain Killer. She had an idea that cholera was worse than the medicine, but then she had never taken any of the stuff. It went down our insides like liquid fire and fairly doubled us up.

—1908 story for children in Hamilton, Bermuda

In 1844 Kneipp filled the world with the wonder of the water cure. Mother wanted to try it, but on sober second thought she put me through. A bucket of ice water was poured over to see the effect. Then I was rubbed with flannels, a sheet was dipped in the water, and I was put to bed. I perspired so much that mother put a life preserver to bed with me . . . three times. When a boy, mother’s new methods got me so near death’s door she had to call in the family physician to pull me out.

—1901 speech

I was the subject of my mother’s experiment. She was wise. She made experiments cautiously. She didn’t pick out just any child in the flock. No, she chose judiciously. She chose one she could spare, and she couldn’t spare the others. I was the choice child of the flock, so I had to take all of the experiments.

—1901 speech

[The measles]: It brought me within a shade of death’s door. It brought me to where I no longer felt any interest in anything, but, on the contrary, felt a total absence of interest—which was most placid and tranquil and sweet and delightful and enchanting. I have never enjoyed anything in my life any more than I enjoyed dying that time . . . The word had been passed and the family notified to assemble around the bed and see me off . . . They were all crying, but that did not affect me. I took but the vaguest interest in it and that merely because I was the center of all this emotional attention and was gratified by it and vain of it.

—Autobiography

![]()