While Washington had been consulting about foreign affairs he had been also asking his advisers for their opinion on a mission that had interested him for months—a tour of the Northeastern States. They urged him to undertake such a journey. His admirers realized that he would be the symbol of government as well as of the struggle that had established American freedom. Strong as was support of the Constitution east of the Hudson, it would be stronger after a visit by him.

If he expected a tour similar to his triumphal progress to New York in April, he was not disappointed. Much that occurred from October 15 to November 13 was, in effect, a repetition of the festivity of the spring—addresses, odes, parades and dinners. Washington was pleased by what he saw of mills in New England and by the beauty and fine dress of the ladies at formal assemblies in Boston, Salem and Portsmouth. His stay in New Hampshire included a landing in Maine, an unsuccessful fishing expedition and much pleasantness in meeting old friends. He stopped on November 5 at the scene of the initial military engagement of the Revolution. As he viewed the positions the men of Massachusetts had occupied at Lexington, he told his companions that British critics had protested to Franklin that it was ill usage for the Americans to hide behind stone walls and fire at the King’s soldiers; whereupon Franklin asked if there were not two sides to a wall. The good humor with which Washington repeated this story was typical of the spirit in which he finished a completely successful tour. Washington returned to New York “all fragrant,” as John Trumbull remarked, “with the odor of incense.”

The President promptly went to work on an accumulation of government mail. His other tasks were more troublesome than numerous. Five days before Washington reached New York, the commissioners sent to negotiate with the Creeks had returned from Georgia and reported failure. As the danger of a war with the powerful Creeks of the Southwest was only one and might not be the worst threat on the frontier, Washington began a study of relations with the unfriendly tribes beyond the American settlements. Until December this was the most complicated of Washington’s puzzles. Some of his other experiences were pleasant. He proclaimed a day of Thanksgiving for November 26 and shared reverently in the services. The day of remembrance was followed by a period of work over Mount Vernon affairs. Washington had, in addition, to be counsellor on numerous financial transactions for which he had a varying measure of responsibility as his wife’s agent or as a trustee. Before these were settled, the President was deep in study, with Knox and Steuben, of plans for organizing the militia.

As the time for the reassembly of Congress approached, Washington extended his activities as host, but he held rigidly to his rule to accept no invitations, not even to funerals. Martha also had placed restrictions on her daily life. Visits had to be made with discretion; she must not go to “public places.” She wrote Mercy Warren:

Though the General’s feelings and my own were perfectly in unison with respect for our predilection for private life, yet I cannot blame him for acting according to his ideas of duty in obeying the voice of his country. The consciousness of having attempted to do all the good in his power, and the pleasure of finding his fellow citizens so well satisfied with the disinterestedness of his conduct, will doubtless be some compensation for the great sacrifice which I know he has made. With respect to myself, I sometimes think the arrangement is not quite as it ought to have been; that I, who had much rather be at home, should occupy a place with which a great many younger and gayer women would be prodigiously pleased . . . I am still determined to be cheerful and to be happy in whatever situation I may be; for I have also learned from experience that the greater part of our happiness or misery depends upon our dispositions, and not upon our circumstances.

A New Year’s reception was preliminary to a session of Congress that began four days late, January 7, 1790. North Carolina had ratified the Constitution November 21; the proposed amendments to that document had met with favor in most of the States. Washington staged with superlative care the delivery of his message on January 8, but his continuing caution deterred him from vigorous advocacy. The paper he read consisted merely of a congratulatory paragraph on “the present favorable prospects of our public affairs” and a series of unexciting proposals for common defence, protection of the frontiers, naturalization laws, uniform weights and measures, the grant of patents, the extension of the post, and the “promotion of science and literature.”

When Congress had been in session a week Secretary Hamilton submitted his plan for the support of public credit, recognized immediately as a bold and strong document. Its basic argument and recommendation were: For their honor, their manifest advantage and their assurance of future credit, the United States must pay defaulted interest on their Continental debt and must fund the principal. To achieve this, the United States must treat all creditors fairly and avoid any discrimination between original purchasers and present holders of obligations. The United States must assume the war-time debts and unpaid interest of the States because these were incurred in support of the common cause and, unfunded, were a costly drain on the resources of America. The terms of such a settlement were equitable and available. A reduction in the average, long-term interest rate of the domestic debt was justified and should be effected by giving creditors a choice of alternatives that included annuities and western lands at twenty cents an acre. Refunding should begin with the foreign and domestic Continental debt; determination of the state debts in a form to make assumption practicable would take time. Interest on the foreign debt at the convenanted rate, and on the domestic Continental debt at 4 per cent would call for $2,239,000 annually. The foreign “instalments” should be met by new loans abroad; interest on the domestic debt could be provided by higher impost duties on wines, spirits, tea and coffee, together with the existing tonnage tax on foreign shipping and an increased excise on spirits distilled in the United States. Twelve million dollars should be borrowed to refund foreign obligations and begin the purchase of American notes and certificates of debt as soon as the general plan was adopted. This was to be done to discourage speculation. Finally, from the assumed profits of the Post Office, a sinking fund was to be created.

This was a dazzling plan and the most impressive possible device to demonstrate to the American people the vitality and good faith of their new government. Washington approved but he foresaw a controversy over assumption of state debts. In deference to the lawmakers who had the right to accept, reject or amend Hamilton’s proposal, he wrote nothing about it and did nothing to commend it to Congress. Members did not stint other legislation while exploring the tangled problems of Federal finance. Neither House looked with favor on the measure to organize the militia, but bills to enact most of Washington’s recommendations were given the consideration they required.

Within his own “department,” where authority had been vested by the Constitution or voted him by Congress, Washington did not hesitate to act. The residence on Cherry Street was not as commodious as Washington desired, nor was it as handsome as he thought the President’s House should be. When he learned that the Macomb House on Broadway might be vacated by the French Chargé d’Affaires, he undertook its lease. Washington convenanted to pay $1000 a year in rent and bargained for some of the fittings at £665. By frequent personal visits and through the diligence of Lear, he rearranged the contents of the rooms, ordered additional stabling and instituted a hurried search for a needed green carpet. New serving plateaux were purchased; lighting arrangements were improved; efforts were made to procure a better cook; and as a final convenience two cows were purchased. Before some of the improvements were completed, Washington moved and on February 26 had his first levee there.

Washington sent to the Senate on February 9 nominations to fill posts that original nominees had declined. Organization of the Judiciary was completed when these were confirmed. No general act was presented for Washington’s signature until February 8 and, after that, none till March 1. In New York the only condition to give new concern to Washington was the vehemence of the debate over Hamilton’s plan and over Quaker memorials against the slave trade. At home the situation was different. From Virginia David Stuart reported: “A spirit of jealousy which may become dangerous to the Union towards the Eastern States seems to be growing fast among us. . . . Col. Lee tells me that many who were warm supporters of the government are changing their sentiments from a conviction of the impracticability of Union with States whose interests are so dissimilar from those of Virginia.” This was a serious development, one to be discussed with a gentleman who, after much delay, had accepted office and on March 21, reported in New York for duty—Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of State.

Washington found Jefferson a wise and ready counsellor on foreign affairs and the diversified questions of public policy concerning which the President asked the opinion of the heads of Departments. The Secretary had useful information also, on the possibility of procuring the release of American seamen captured and enslaved by Barbary pirates. Jefferson disclosed a strong opinion concerning the rank at which American diplomatic representatives should be accredited to European courts. It would be better, he thought, to send Charges of prestige rather than Ministers of comparative lower standing in that category. The only exception, in his judgment, should be at Versailles. Washington was not without hopes that an American Minister would be well received at the Court of St. James’s, but he had particular reason at that time for getting all the advice he could: The House had under consideration a bill for “providing the means of intercourse between the United States and foreign nations”: Was it the prerogative of the President or the right of Congress to say at what rank diplomatic agents should be accredited, and if they were to have position that called for a considerable establishment, how was it to be financed? Jefferson thought the President free to decide whether he would send an Ambassador, a Minister or a Chargé to a given post, provided the expenditures did not exceed the appropriation. To have this view accepted in all its parts and get money enough for the men needed at foreign capitals Washington had “to intimate”—the verb was his—that he planned to send to Britain, as well as to France, an agent with the rank of Minister. Even after this cautious intervention, the requisite funds were not made available until months after Jefferson’s arrival.

The lawmakers were in a contentious mood. The reason was the bill “to protect the public credit,” the first measure to carry out the recommendations in Hamilton’s report. The House was almost evenly divided—a condition that Washington thought particularly regrettable where the issue was one of high importance. Cleavage was not sectional. Massachusetts’ supporters of assumption were exceeded in vehemence of argument by Representatives of South Carolina. Over and over the appeal was: These debts of the States were contracted for a common cause; the States were merely the agents of Congress; debt was the price of liberty. Madison met this with a reminder that assumption did injustice to the States which had done their duty by their creditors and now were called on to contribute to those States that had not done like duty. Almost without exception, the magnitude of the debt of a given state was the gauge of its Representatives’ zeal for assumption. Men jealous of the rights of their States warned that assumption would increase the popularity of the Federal government and would weaken the States. Daily, endlessly, the debate went on.

Washington listened as the arguments were repeated in the house on Broadway, but he faced now a new and perplexing problem. The State of Georgia was alleged to have sold to private land companies large tracts that lay beyond the line of territory reserved by treaty to the Choctaw and Chickasaw and part of the Cherokee tribes. This was done after Georgia had ratified the Constitution and thereby relinquished all right to deal with the Indians. If the savages were to be restrained from violence and depredation, their rights under existing treaties must be respected, to the extent, at least, that if lands were occupied, payment should be made and new treaties negotiated. Instead of coercion there should be an opportunity for Georgia to withdraw from her position and, meantime, to preserve the status quo. It might be well to send a representative to the Indians in order “to explain to them the views of government, and to watch with their aid the territory in question.”

About this time the President found himself with a bad cold. The next day he was worse. Martha took charge of the sick-room, and, as Lear was absent on his honeymoon, Major Jackson assumed direction of the office and made arrangements for medical attendance. Besides Dr. Bard, he called in Drs. John Charlton and Charles McKnight, but their combined treatment did not halt the progress of a serious form of pneumonia. Alarm seized the household. By May 12 the General’s condition was so critical that the physicians asked for the counsel of Dr. John Jones of Philadelphia. Major Jackson had an express dispatched immediately and exerted every effort to have the famous surgeon make the journey with secrecy, but within a few days it was known that Washington was dangerously ill and that his death was not improbable.

On May 15 the General seemed to be close to the end. Doctor McKnight said frankly that he had every reason to expect the death of his patient. Shortly after midday, Washington seemed to be at the last of his hurried and shallow respiration. Then, about four o’clock, he broke into a copious sweat and his circulation improved. Within two hours the change was definite: he had passed the crisis. On the sixteenth he was so much improved that members of the household began to hope he was out of danger. By the twentieth this was the general opinion. After that Washington was himself again. Washington’s reflections were calmly simple: He had suffered two illnesses of increasing severity within a year, he said; the next doubtless would be the last. Meantime, physicians’ orders to take more exercise and do less work were hard for even so well disciplined a man as he to obey. His comfort was the prospect of going to Mount Vernon for a vacation if Congress took a recess.

Members had not advanced their legislation satisfactorily during the month Washington had been ill and convalescing. Seven acts had been passed, none of first importance, but neither the bill to provide for the public credit nor the measure to establish the seat of government had received approval. On the contrary, the two had become entangled in a manner that excited the politician and made the citizen shake a puzzled head. When division of the House of Representatives had been tested, assumption of state debts had been rejected in Committee of the Whole by a majority of two. At first, after that defeat, the resentment of New Englanders and South Carolinians ran so high that they were suspected of planning to reject all funding at that session of Congress. They were too wise and too much interested to be guilty of any such blunder. They rallied their forces while the Virginians continued in unyielding opposition to every proposal that the debts of the States be assumed. To the surprise of some members of Congress, tempers suddenly cooled. Hamilton, Jefferson, Robert Morris and others took advantage of this and made common cause. The Secretary of the Treasury had resolute ambition to see his funding plan succeed, but he lacked a vote or two and he must find them. Jefferson saw no reason why he should not use his influence with members of Congress in what he considered good causes—such, for example, as seating the government on the Potomac. Morris was desperately anxious to have the government moved temporarily to Philadelphia, doubtless in the hope the choice might be in perpetuo. Out of these interests came agreement whereby the advocates of assumption of state debts were to effect conversion of a few doubters, in return for which Philadelphia was to be the seat of government until 1800. After that the capital was to be near Georgetown, on the Potomac. The bill “for establishing the temporary and permanent seat of the Government of the United States” was passed and presented to the President July 12. Those who favored New York as the capital and those who opposed assumption of state debts were furious.

The President signed the bill on July 16. For this action Washington received what was almost the first direct newspaper censure that had been leveled at him since he had taken office. It was mild, guarded intimation that Washington lacked gratitude to New York. Doubtless conversation of disappointed members of Congress was sharp, but there is no record of any rebuke from the floor, nor does any letter by Senator or Representative allege that Washington was party to the bargain. Washington had hoped the valley of the Potomac would be chosen as the site of the capital, but if any member’s vote was affected by the President, it was because the individual wished to do what Washington desired and not because the General asked him to do it.

The bill to move the capital was followed in little more than a fortnight by the funding measure. In final form, the bill embodied Hamilton’s foundation of a new foreign loan, payment of accrued interest, and assumption of state debts; but the superstructure was simpler than in his design. If the Secretary might claim to be the architect, he still owed thanks to the draughtsmen of Congress. Washington believed in the bill and signed it with a sense of relief that the dangerous issues involved in it had been settled.

The weeks during which Congress fought over debt settlement and the seat of government witnessed several developments that encouraged or puzzled the President in his convalescence. On May 29, Rhode Island ratified the Constitution. Maj. George Beckwith, aide to Lord Dorchester (formerly Sir Guy Carleton), Governor of Canada, sought out Hamilton on July 8 and, in traditional diplomatic indirection, hinted that Britain not only might settle differences with America but also might be willing to enter into an alliance. In event of war between England and Spain, Beckwith remarked, the United States would find it to their interest to uphold Britain. There was much besides, in the Major’s conversation, but these were the points of strongest emphasis.

Hamilton reported this to Jefferson and went with the Secretary of State to inform the President what had occurred. Washington was usually cautious in his conclusions and did not clinch them until he had deliberated and heard all that the best men around him had to say. This time his judgment was clear and quickly shaped: The British had determined not to give an answer to Gouverneur Morris in London until they ascertained by Beckwith’s indirect approach whether the United States were willing to make common cause with them against Spain. If America did this, then the British would negotiate a commercial treaty and would “promise perhaps to fulfil what they already stand engaged to perform” under the treaty of 1783. The result of this and another diplomatic fencing bout between Hamilton and Beckwith was a decision by Washington to let it be impressed that the United States had no understanding with Spain and had not settled with that country the question of the navigation of the Mississippi. Beyond this, civility and reticence were the course of prudence on the part of a country that desired to remain neutral and at peace with all foreign powers.

Thus the matter stood until mid-August, when there was intimation that if England and Spain opened hostilities Lord Dorchester might wish to descend the Mississippi through the territory of the United States and attack Louisiana or its outposts. If Britain made a request for her troops to have unhindered passage, what should Washington do? He thought such application would be made by Dorchester and believed that no decisive answer should be given, but he sought the advice of Hamilton, Jefferson and Knox, and of the Vice President and the Chief Justice as well. The President found these counsellors divided. Diversity of counsel underscored the warning the President’s judgment gave him: he would have an unhappy decision to make—one that would outrage the West or divide the East—if the British started southward. He could not tell, as yet, whether the two powers who together hemmed in his country would go to war—with the prospect that British victory would set King George’s ramparts north, west and south while the Royal fleet ruled the Atlantic.

In the exchanges between Hamilton and Beckwith there had been polite intimation and horrified denial that Britain had been exciting northwestern tribes to violence and American frontier officers had been threatening British posts verbally. The fuel for a conflagration was scattered widely north of the Ohio. Although the Six Nations no longer were a firebrand, the Miami and Wabash tribes were attacking boats on the Ohio and Wabash and were crossing into Kentucky on raids of massacre and arson. Efforts to make peace had been futile. Washington, St. Clair and Knox were of one mind in belief that nothing short of a vigorous, punitive campaign would dispose of a danger that otherwise might stop all movement on the Ohio. Washington instructed St. Clair, as Governor of the Northwest Territory, to prepare the expedition and call out militia to reenforce a small contingent of regulars, who were to have some artillery with them. On July 15 troops, presumably about fifteen hundred, were assembling at Fort Washington on the Ohio. With good fortune and good leadership, they might strike a blow in the autumn that would clear the river and make the settlements secure. The commanding officer, Brevet Brig. Gen. Josiah Harmar, had served with Pennsylvania troops during the Revolution, but was not well known to the President.

South of the Ohio, most of the Indians were thought to be well-disposed, though a handful of Cherokee and Shawanese bandits were proving troublesome. As for the Creeks, Knox, through a shrewd and patient agent, Col. Marinus Willett, at last had accomplished what had seemed impossible: Willett had prevailed on Alexander McGillivray, the Creeks’ half-breed Chief, to come to New York with twenty-nine head men. On their arrival Knox supervised negotiation of a pact by which the Creeks yielded to Georgia disputed lands on the Oconee but refused to give up their hunting-grounds southwest of the junction of that river and the Ocmulgee. Washington shared in some of the entertainment of the Indians; and gave his approval to the various measures Knox desired at the hands of Congress. He wrote Lafayette that except for the crimes of a few bandits, the treaty “will leave us in peace from one end of our borders to the other.”

The adjournment of Congress on August 12 left Washington free to execute a plan he must have fashioned from the time he received news that Rhode Island had ratified the Constitution. He had not entered that State during his tour of New England. Now he would go there, meet the leaders, see the people and make it plain that he no longer kept in his heart resentments petty spokesmen of the State had aroused. The journey, begun on August 15 with Jefferson, Clinton and other notables, was the easiest Washington had made in years. The most noteworthy occurrences of the brief visit were Washington’s answers to three of the addresses delivered him. Instead of perfunctory, polite avowals, he made thoughtful statements, half philosophical and admirably phrased. He told the representatives of the Jewish Congregation of Newport:

It is now no more that tolerance is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people, that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights. For happily the government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support. . . .

Washington left Providence August 19, reached New York on the twenty-first, and took up his part of another task: the transfer of the seat of government to Philadelphia. The President took it upon himself to supervise the moving of those contents of his residence that were not too bulky or too much a part of the house to be taken down; the labor was one that Washington performed zestfully. Rehabilitation, literal or metaphorical, made a peculiar appeal to him. Details were left to Lear, who had the rare and needful combination of diligence and patience. Lear’s service was more difficult and more nearly indispensable because of reorganization of the office staff. Humphreys was going to Spain and thence to Portugal on diplomatic assignment; Lewis was returning to Virginia to act as steward while George Augustine Washington went “to the mountains” in hopes of physical recovery; Nelson went, also, to Virginia on a vacation. The President consequently was left with two secretaries only, Lear and Jackson.

By August 30 all matters were arranged; amenities of departure observed, and accounts settled. On the twenty-eighth the Governor of New York, the Mayor of the city and the Aldermen had been the President’s guests at dinner. In spite of his request for an unceremonious leave-taking, the Governor, the Chief Justice of the United States, the heads of Federal departments and the executive officers, state and municipal, came to his house on the thirtieth and escorted him with the utmost good will to the wharf. Although New York was losing the “seat of government” and the prestige accompanying that honor, the last minutes were impressive: “All was quietness,” reported the New York Daily Advertiser, “save the report of the cannon that was fired on his embarkation . . . the heart was full—the tear dropped from the eye; it was not to be restrained; it was seen; and the President appeared sensibly moved by this last mark of esteem. . . .”

Lear had requested that there be “no more parade on [the President’s] journey than what may be absolutely necessary to gratify the people.” All went quietly until, in the afternoon of September 2, Washington reached the vicinity of Philadelphia. There he was met by a troop of light horse, militia companies and numerous citizens. Bells were rung, a feu de joie was tendered—everything was as if the President were visiting the city for the first time. Dinners and other ceremonies were offered, but at least some of them would have been declined with the excuse of a hurried journey had not Martha fallen sick. As it was, the President enjoyed various affairs and found time to satisfy himself concerning arrangements for a residence. The municipal corporation of Philadelphia had rented for him the home of Robert Morris, probably the handsomest dwelling in the city. Washington wrote Lear: “It is, I believe, the best single House in the City; yet, without additions it is inadequate to the commodious accommodation of my family”; and went on to describe the changes he thought necessary and the servants he would require. Then, on the sixth, Washington left for Mount Vernon. No accident worse than a harmless overturn of the chariot and the wagon delayed the remainder of the journey, and the entourage reached Mount Vernon on September 11.

Return to Mount Vernon raised the spirits of Washington and contributed to full restoration of his health. He did not have any particular problem on the plantation other than his usual need of ready cash. Correspondence did not take any large part of his time. He was able to make a leisured examination of what was being done in the improvement of the Potomac by the company he had organized and headed. Little public business was submitted for his review, though Hamilton did pass on a rumor that Spain had admitted the right of the United States to the free use of the Mississippi.

The one official concern was over absence of any report from General Harmar, who by this time was supposed to have marched against the Miami Indians. Doubt of success rose in Washington’s mind when he learned St. Clair had notified the British at Detroit of Harmar’s expedition and assured them the United States forces were not marching against that post. The British, in Washington’s opinion, might pass this information to the Indians whom Harmar was to punish. When Washington heard later that Harmar was believed to be a heavy drinker, the President virtually abandoned hope of any substantial achievement by the American column. Knox could say nothing to reassure his Chief.

Leisure and interest prompted Washington to spend hours in planning how the Morris house in Philadelphia was to be enlarged and furnished as the official residence of the Chief Executive. No less than nine letters to Lear were devoted to the move to the Quaker City and the adornment of the dwelling. The only important point in all the long letters was insistence by the President that the house be leased by him in regular form and not accepted with the rent paid by any public body in Pennsylvania.

Washington and his party reached Philadelphia again the morning of November 27 and went at once to the Morris house. Lear had made it habitable even though the remodeling was not complete. The condition of public affairs was good and bad—good in the general prosperity and content of the people, bad in the absence of news from Harmar and in the continued hammering of Anti-Federalist newspapers, the New-York Journal in particular. These failed to raise a clamor or defeat any considerable number of members of Congress who stood for reelection that autumn. Washington proceeded to prepare for the coming session of Congress. On December 8 he drove to the Hall of Congress and in the Senate Chamber made his brief address, which he devoted principally to finance and Indian affairs. He had favorable credit standing to report and the recommendation that the Federal debt be reduced “as far and as fast as the growing resources of the country will permit. . . .” As for Indian depredations, it probably was fortunate that the flavor of an auspicious opening was not soured by knowledge of the failure of Harmar’s expedition. At the moment, Washington could say only “the event of the measure is yet unknown to me.” The President gave a paragraph to the situation in Europe and the probable curtailment of available shipping for American exports. A more cheerful statement dealt with the admission of Kentucky to the Union. The remainder of the address was devoted, briefly, to mint and militia, weights and measures, the post office and the post roads.

Knox’s report on Indian affairs, submitted on the ninth, disclosed abundant reason for Harmar’s expedition, but gave no account of what had befallen Harmar and his men. When the official report at length was received, it was found to be a complacent review of operations represented as successful, though actually they were a bloody failure in the defeat of two detachments and the loss of 180 men. Washington’s candor in keeping Congress informed and the apparent adequacy of Knox’s preparations saved the President from criticism.

Hamilton took the centre of the stage a week after the session opened and submitted two reports that forthwith made every member of Congress his advocate or his critic, to the exclusion of almost every other subject of legislative debate. Both papers were in obedience to a resolution by the House of Representatives at the previous session for a report on any further action necessary for establishing the public credit. Hamilton divided his answer into two parts, one a series of suggestions for new and higher excises, the other a plan for the establishment of a central bank. A proposal for heavier taxes on imported spirits was coupled with one for excises on liquors distilled in the United States. Estimated net revenue would be $877,500. As Hamilton designed the bank, which he frankly styled “national,” it was to have a capital stock not exceeding $10,000,000, of which the President was to subscribe $2,000,000 on account of the United States. The bank was to establish branches throughout the country at its discretion and have an exclusive Federal charter; its notes and bills, if payable on demand in gold and silver coin, were to be receivable in all settlements with the United States. Details were well considered, the Bank of England serving as a model, but no provision had interest comparable to that of the exciting question: Did Congress have the power to charter any bank?

While legislators debated this issue in the taverns and in the boarding houses, before they so much as raised it on the floor, Washington labored over a small but a singularly perplexing series of tangles and wrangles. The reassurance of friendly Indians was particularly difficult when plans for new operations against the Miami scarcely were concealed. Preliminaries had to be arranged for laying off the Federal District as the permanent seat of government. Washington had to decide what further instructions should be given Gouverneur Morris, whose unofficial inquiries in England had brought to light no inclination on Britain’s part to execute the provisions of the treaty of peace or open friendly commercial relations on a basis of equality. The President’s conclusion was against further effort, for the time being, to press for any accord. A considerable volume of other legislation, including measures for the admission of Kentucky and Vermont to the Union, occupied Congress more than it involved the President. The sole recommendation of Washington’s that met with virtual denial was for the uniform organization of the militia. This was debated in the House and killed by postponement.

Although little of this legislation aroused heat, no essential part of the bill for the excise on spirits and scarcely a clause of the measure for the establishment of the national bank failed to stir the coals of controversy. Washington felt that South and East were arrayed unpleasantly against each other—the Southern delegations in opposition and the New Englanders for the two measures—but it seemed to him that the debates were conducted with “temper and candor.” The bank bill originated in the Senate; the excises, of course, were for the House to initiate. The Senate passed the bank bill January 20, 1791, and the House the excise legislation a week later. Then the two chambers exchanged bills. The Representatives made short work of the measure to establish the bank and on February 8 accepted it.

Washington had to decide for himself the constitutional question that had divided both chambers: Should he sign or disapprove the bill to charter the Bank of the United States? The Attorney General was asked for his opinion, which was adverse. Next, Jefferson’s observations were sought; they were forthcoming with convinced precision. The bill, he said, was unconstitutional, because Congress was not vested with specific authority to create such a corporation and under one of the amendments then in process of adoption, “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” Jefferson’s arguments were set forth succinctly and without a doubt concerning the absolute correctness of interpretation; but at the end was this candid counsel: “. . . if the pro and the con hang so even as to balance [the President’s] judgment, a just respect for the wisdom of the Legislature would naturally decide the balance in favor of their opinion. It is chiefly for cases where they are clearly misled by error, ambition, or interest, that the Constitution has placed a check in the negative of the President.”

Washington gave Hamilton “an opportunity of examining and answering the objections” and asked Madison to draft a proper form for returning the bill to Congress in event the decision was to refuse approval. Madison responded with a document conveniently phrased for returning the bill either on the ground of unconstitutionality or on that of a lack of merit in the measure. The argument advanced by Madison against constitutionality was condensed into a single sentence: “I object to the bill,” Madison would have the President say, “because it is an essential principle of the government that powers not delegated by the Constitution cannot be rightfully exercised; because the power proposed by the bill to be exercised is not delegated; and because I cannot satisfy myself that it results from any expressed power by fair and safe rules of implication.” Hamilton’s answer was a complete review and attempted refutation of substantially everything Jefferson and Randolph had said. Hamilton’s basic argument was:

. . . it appears to the Secretary of the Treasury that this general principle is inherent in the very definition of government, and essential to every step of the progress to be made by that of the United States, namely: That every power vested in a government is in its nature sovereign, and includes, by force of the term, a right to employ all the means requisite and fairly applicable to the attainment of the ends of such power, and which are not precluded by restrictions and exceptions specified in the Constitution, or not immoral, or not contrary to the essential ends of political society.

Thus were Washington’s closest counsellors divided, to his distress and embarrassment, over the width and reach of the foundations on which the structure of government was to rise. From the beginning of the effort to give America a new Constitution, his controlling principle had been the simplest: the United States must have a strong central government if they were to keep their freedom. Because his reasoning and conviction were altogether on the side Hamilton championed, he signed the bill on February 25. The excise measure came to his desk March 1, and, as it involved no constitutional issue, it received his signature the next day.

Troubled as the government at Paris was in its desperate struggle at home, the only other large question of controversy on the floor of Congress was a French protest against the tax on tonnage of ships entering the United States. Washington asked Jefferson to report on this and the Secretary, friend though he was of France, found her contention invalid for reasons he set forth at length. He admitted that policy might dictate concession but outlined explicitly the basis of what might be said in rejecting the protest. The Senate decided to maintain the interpretation of the Secretary. When Congress at length adjourned on March 3, Washington felt that besides passing the great contested measures, the two houses “had finished much other business of less importance, conducting on all occasions with great harmony and cordiality.” The majority probably agreed with Washington and shared Abigail Adams’ belief: “Our public affairs never looked more prosperous.” The First Congress had passed out of existence; a time of reckoning had come.

Washington was pleased not only with the achievements of the Congress but also with his success in learning his new duties. He wrote Lafayette that the American public had accepted Federal laws, which had been moderate and wise. “The administration of them,” said he, “aided by the affectionate partiality of my countrymen, is attended with no unnecessary inconvenience. . . .” He owed this lack of difficulty to the same conditions that had aided him in 1789—his own cautious, sound judgment, the absence of crisis, the consideration of legislators, the undiminished esteem in which Americans held him, and the success of his dealings with Congress and with the men he had chosen as heads of the departments. Hamilton and Jefferson were Washington’s closest advisers by this time and were the executive lieutenants most esteemed by Congress. Inside Congress Madison was less frequently consulted during the winter of 1790-91, not because of any cooling of affection but because he was engrossed in his labors as a legislator. Washington’s unofficial communications with Congress—and some of his regular reports—were through the heads of departments. Always the approach was as deferential as when the Commander-in-Chief had been in the field during the war; in his new position he lost none of his consideration for the pride and prerogative of lawmakers. His dealings with governors, state legislatures and officials in general conformed to the same criterion, but he insisted that this golden rule of administration be followed by others as well as by himself, and he resented any encroachment by the States on the domain of the Federal government.

Within the executive precinct of the Federal government, heads of Departments exercised initiative and freedom of thought. They were at liberty to express their own views in papers they laid before Congress at his direction as well as in reports prepared on order of Congress and transmitted directly to that body. Nor was there the least complaint on the part of Washington when any document he sent to Congress was referred to one of his subordinates for study and independent report. In foreign affairs Washington had no unvarying policy of administration. He might conduct direct correspondence for a time with American representatives abroad and later might request the Secretary to act; or he might take over from Jefferson; or, still again, both he and his lieutenant might write a Minister or Chargé within the same week. On occasion, too, the President would content himself with making suggestions to the Secretary of State. Washington employed the heads of departments substantially as he had used the members of his military family during the war. Each man was consulted if and when the President desired that individual’s judgment on a given issue, whether or not it was in the department for which that person was directly responsible. This had been accepted without misunderstanding and sometimes had been regarded as a convenience.

Differences over the banking bill soured amity between Jefferson and Hamilton. The opinions they had given Washington on the constitutionality of that measure had been those of men with different philosophies of government and not merely with contrary views of the implied powers of Congress. Rivalry between the two was becoming so apparent that Washington could not be unaware of it, but he chose to ignore it, and he took pains to avoid any treatment of one or the other that might seem preferential or partial.

Philadelphia most certainly was pleased with him and was able to demonstrate often during the winter its old affection for him and its pride in being the seat of his administration. He and Martha held their levees as usual. Shining affairs were the First Lady’s Christmas Eve entertainment, the New Year’s Day reception, and the ceremonious observance of the President’s birthday February 22. Formalities were as strictly followed as ever. Washington carefully walked the line he had set for himself and respected all the amenities, but he was beginning to tire of the pomp of public appearance and was not insensitive to criticism of monarchical practices.

The President had had a series of personal and family chores to discharge during this season in Philadelphia, some so tedious and vexatious that they would have overtaxed his patience if they had not included two gratifying events. One was the birth in the President’s own house of a boy to Tobias and Mary Lear, who were residing there on the hearty invitation of the General and Mrs. Washington. This young gentleman was christened Benjamin Lincoln Lear, with Washington as godfather. The other occurrence was an offer by John Joseph de Barth to purchase at a fair figure all of Washington’s lands on the Ohio and the Kanawha, an offer gladly accepted.

Washington long had been making plans for a tour of the Southern States and as quickly as he could he disposed of the business that had to be transacted if the wheels of government were to revolve smoothly during an absence of three months, part of which would be in remote areas of the country. Then, on March 21, with Major Jackson, much equipment and a cumbersome entourage of five persons, he set out for the Potomac on what he regarded as the first stage of the Southern journey.

The duties Washington now had to perform were exceedingly interesting to an old surveyor. Under the law he had signed July 16, 1790, “for establishing the temporary and permanent seat of the government of the United States,” he was required to appoint three commissioners and direct their survey of the district where the Federal City was to rise. The President was to decide how much land was to be acquired on the Maryland side of the river for public use. This land was then to be purchased or accepted as a gift, and on it, “according to such plans as the President shall approve,” the commissioners were to provide “suitable buildings.” Washington had named two citizens of Maryland—Thomas Johnson, an able former Governor, and Senator Daniel Carroll of Rock Creek. The third commissioner was David Stuart, whose wife was Jack Custis’s widow. Maj. Andrew Ellicott, an experienced surveyor, had been sent to the Potomac in February to take a general view of the area and suggest “lines of experiment” for determining the exact “seat of government.” Ellicott had been followed by Maj. Pierre Charles L’Enfant, who was to make detailed surveys with an eye to the location of public buildings. These appointments had been made at a time of intense excitement on the part of landowners. Almost every man who held title to an acre in the vicinity was dreaming of fortunes to be made when farms of undistinguished fertility became, overnight, priceless lots in the centre of a city.

In such a situation, George Washington, veteran in land buying, could be a wise, even shrewd, guide for the cautious President of the United States. He maintained tight-lipped secrecy concerning final bounds of the district and reserved as much latitude of purchase as possible. If one group of property owners demanded an exorbitant price, he could make a show, at least, of looking elsewhere. Washington created as much of an air of buyer’s independence as he could. After he reached the area and examined the various tracts, he called the landholders together on March 29 and explained that Georgetown and Carrollsburg might defeat their own ends by rivalry or excessive prices for property desired by the Federal government. The case was not one of competition but of cooperation. Together, the towns did not cover more ground than would be required for the city. The wisdom of this counsel was for the moment irresistible. Next day Washington was informed that all the principal owners would accept the terms he proposed. A total of between three and five thousand acres was to be ceded to the United States, with these provisos: the whole was to be included in the Federal City and laid off in lots; alternate lots were to remain the property of the former proprietors, who were to donate ground for streets and alleys; for the land taken by the government, twenty-five dollars an acre was to be paid. Much pleased with this, Washington gave instructions for making the survey and for other action necessary to execute the agreement.

For his long journey through the South, a region of notoriously bad, sandy roads, Washington had prepared carefully a list of distances and contingencies; and he fixed precisely the number of days he was to spend in each of the principal towns he planned to visit. The whole arrangement he termed his “line of march,” which he was to follow with no other companions than Major Jackson and the servants. Had he been superstitious he would have doubted at the very outset the wisdom of his venture, because in crossing the Occoquan, on April 7, the day of his start south, one of the animals harnessed to his new, light chariot fell into the stream, fully harnessed, and so excited the others that all went overboard. Quick work prevented loss.

At Fredericksburg, where he spent two nights and a day, he had a second disquieting experience: John Lewis, the only surviving son of Fielding Lewis by his first marriage, told of a recent interview with Patrick Henry, who made no secret of his financial interest in the so-called Yazoo Company. When Lewis had inquired how the company expected to deal with the Indians, Henry had said that an appeal would be made to Congress for protection. If this was denied, the Yazoo proprietors would organize their own force under Brig. Gen. Charles Scott. That was an ugly threat, if it was not mere gasconade. “Schemes of that sort,” Washington reflected a little later, “must involve the country in trouble—perhaps in blood.”

A third unpleasantness awaited Washington in Richmond, where he received ceremonious welcome April 11, and, along with salute and salutation, mail from Philadelphia. Included was a letter in which Lear remarked that Attorney General Randolph was in danger of losing slaves brought from Virginia because of a Pennsylvania law which provided that adult bondsmen would be free six months after their owner, moving into the State, became a citizen. Washington thought the difference between his situation and that of Randolph gave reasonable assurance that the law did not apply to him. In order to appear in Pennsylvania courts, Randolph had become temporarily a citizen of Pennsylvania; Washington had not. At the same time, the President felt that someone might “entice” his servants and that the Negroes might become “insolent” if they thought themselves entitled to their freedom. His old regard for his property asserted itself in the letter he wrote Lear:

As all [the slaves of the Presidential establishment] except Hercules and Paris are dower negroes, it behooves me to prevent the emancipation of them, otherwise I shall not only lose the use of them but may have them to pay for. If upon taking good advice, it is found expedient to send them back to Virginia, I wish to have it accomplished under pretext that may deceive both them and the public; and none, I think, would so effectually do this as Mrs. Washington coming to Virginia next month. . . . This would naturally bring her maid and Austin, and Hercules under the idea of coming home to cook whilst we remained there, might be sent on in the stage. Whether there is occasion for this or not, according to the result of your inquiries or issue the thing as it may, I request that these sentiments and this advice may be known to none but yourself and Mrs. Washington.

Slavery, in his eyes, was a wasteful nuisance, but so long as it existed in a country where the sentiment of honest men was divided over it, he would safeguard his rights with the least public offence.

Ceremonies in Richmond followed a familiar pattern and did not over-crowd the two days and a half that he gave to the capital of his native state. With Gov. Beverley Randolph and the directors he examined the canal the James River Navigation Company was constructing around the falls and had opportunity of talking with Col. Edward Carrington, his appointee as Marshal of the District of Virginia. The Colonel thought the people well disposed to the Federal government and ready to approve action properly explained to them. Washington heard this with much satisfaction. One of the reasons for making the tour was his wish to ascertain at first hand what the people thought of the government.

From Richmond the President drove to Petersburg on the morning of the fourteenth and there received all the honors the town could bestow. He had been warned that the next stages of his journey would be “dreary” and was not unprepared for the full, flat pinelands through which he had to pass, mile on mile. Although he soon came into a region new to him, he found little of interest except the river valleys and the possible improvement of navigation. With stops at Halifax, Virginia, and Tarboro, North Carolina, Washington proceeded to Newbern, where he had what he described as “exceedingly good lodgings.” The welcome fitted the quarters, but the next stretch of the journey, the long one to Wilmington, was almost bad enough to efface the pleasant memories of the hospitable town at the confluence of the Neuse and Trent Rivers.

Wilmington was hospitable and interesting. Washington looked upstream, too, and speculated on the possibility of extending transportation as far inland as Fayetteville, which was described to him as already a “thriving place” with large markets for tobacco and flax seed. From Wilmington the road traversed more stretches of “sand and pine barrens,” though he was told of better farms and a population less sparse back from the traveled route. For part of the way to Georgetown, there were no inns, but, while this compelled Washington to violate his self-imposed rule against the acceptance of private hospitality, the absence of public houses added to the comfort of his travel.

On April 29 Washington had his first contact with the rich society of South Carolina. This was at Clifton House, the seat of William Alston. Alston had the reputation of being “one of the neatest rice planters in the State of South Carolina and a proprietor of the most valuable ground for the culture of this article.” Washington looked at the plantation with eyes that were keenly appreciative of trees and thriving crops. At Clifton House were Gen. William Moultrie, Col. William Washington and Edward Rutledge, who had come out to escort their State’s guest to Georgetown and thence to Charleston. All three were interesting men. Besides his kinship with the President, William Washington had the fine reputation he had acquired in the main Continental Army and the fame he had won in the Southern Department. Moultrie was an officer of shining reputation, valiantly won. Edward Rutledge was the brother of the Chief Justice of the State, John Rutledge. These gentlemen brought the written greetings of Gov. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and invitations from him.

In Georgetown, on the thirtieth, he attended a public dinner and during the afternoon bowed at a tea party to “upwards of fifty ladies.” He interested himself in Georgetown and its waterways, but he felt that the town was overshadowed by Charleston, where he had decided to spend a week. May 1 was given to travel to Gabriel Manigault’s plantation, where Washington spent the night. The next morning began an extraordinary week. The ceremonial crossing from Haddrel’s Point to Charleston harbor was spectacular. A twelve-oared barge was rowed by American sea captains; two boats conveyed musicians; almost all light craft in the vicinity of Charleston attended the President; on approaching Prioleau’s Wharf, Washington received a hearty artillery salute. After a formal landing and welcome, he was driven to the Exchange to see the procession pass and, when the last contingent had saluted him, he went to the residence of Judge Thomas Heyward, which had been leased and adorned for his occupancy.

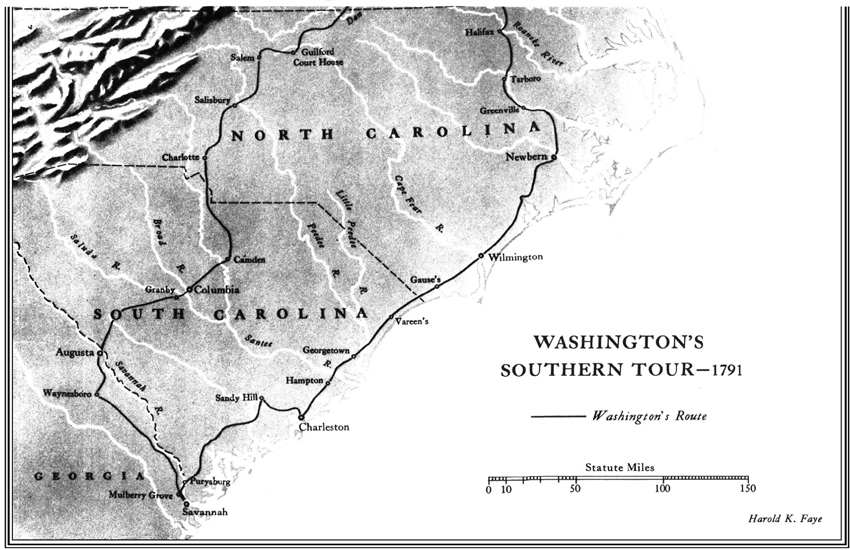

MAP / 16

WASHINGTON’S SOUTHERN TOUR, 1791

Not even his “triumphant progress” from Mount Vernon to New York in 1789 equalled the entertainment that began the hour he arrived in the Carolina city. He held three receptions, attended two breakfasts, ate seven sumptuous formal dinners, listened and replied to four addresses, was the central figure at two assemblies and a concert, rode through the city, went twice to church, observed and praised a display of fireworks and drank sixty toasts. At the assembly on the evening of May 4, “the ladies,” according to the City Gazette, “were all superbly dressed and most of them wore ribbons with different inscriptions expressive of their esteem and respect for the President such as: ’long live the President,’ etc.” Two evenings later, at the ball given by Governor Pinckney in Washington’s honor, the homage of his feminine admirers was in their hairdress. Nearly all the coiffures included a bandeau or fillet on which was painted a sketch of Washington’s head or some patriotic, sentimental reference to him.

A different attraction of the city was the line of its defence in the campaign of 1780. With deepest interest, the old Commander-in-Chief went over the ground in the company of General Moultrie and other veterans who knew every foot of it, and he concluded that the defence had been altogether honorable. Other visits of military interest were to Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island and Fort Johnson on James’s Island. Although little remained of these earthworks, Washington had the privilege of hearing the repulse of the British fleet on June 28, 1776, described by General Moultrie, who not only was responsible for it but was able to recount it with the skill of a practiced raconteur.

En route to Savannah May 9/11 the President violated his rule against the acceptance of lodging at private homes; but he explained this carefully in his diary: He spent one night at Col. William Washington’s plantation, Sandy Hill, from “motives of friendship and relationship,” and he stayed at O’Brien Smith’s on the tenth and Thomas Heyward’s on the eleventh because there were “no public houses on the road.” The next day carried him to the Savannah River at Purysburg, where notables of the fine city downstream were awaiting him with boats for the vehicles and luggage and an eight-oared barge for Washington and the committee. On the way, the President went ashore at Mulberry Grove for a brief visit to the widow of Nathanael Greene. Adversity had overtaken this brilliant woman who had enlivened many a black night in wartime winter quarters. In the brief time Washington had for this first call on her in her southern home, he could not discuss her business affairs, nor would he have talked of them, probably, had his stay been longer, because it was likely he might be called upon, as President, to sign or disapprove legislation for her relief.

With wind and tide against the bedizened sea captains at the oars, it was 6 P.M. on May 12 when the President reached Savannah, but the townsfolk still were awaiting him. The next two and a half days were crowded with ceremonial, and he visited the scene of the attempt the Comte d’Estaing and General Lincoln made in September-October 1779 to wrest Savannah from the British garrison.

From Savannah Washington returned by road to Mulberry Grove, dined with Mrs. Greene, and went on to a tavern where he lodged. Thence he rode to Augusta, which he reached May 18. Two days and a half were spent in the enjoyment of the town’s hospitality. Next after Washington left Augusta May 21 was a halt of a day and a half at Columbia, South Carolina, and, unexpectedly, of a second day there because of the bad condition of a horse. Except for a welcoming escort and a public dinner at the unfinished State House, the visit to Columbia was without incident. The miles stretched out northward. An overnight halt and a public dinner at Camden on the twenty-fifth were followed by a careful examination of the ground of the action between Greene and Lord Rawdon April 25, 1781. Farther on Washington viewed the scene of the rout of Gates by Cornwallis August 16, 1780, and later wrote down his conclusion, with generosity towards the American comrade he had distrusted for years:

As this was a night meeting of both armies on their march and altogether unexpected, each formed on the ground they met without any advantage in it on either side, it being level and open. Had General Gates been half a mile farther advanced, an impenetrable swamp would have prevented the attack which was made on him by the British army, and afforded him time to have formed his own plans; but having no information of Lord Cornwallis’s designs and perhaps not being apprized of this advantage it was not seized by him.

After Camden, Washington found nothing of importance on the road to Charlotte, North Carolina. Charlotte itself was disappointing but the approaches to it were through better farm lands than Washington had seen in days, and the district between Charlotte and Salisbury seemed to him “very fine.”

The last day of May brought a journey to Salem, a little Moravian town that gave Washington a welcome thus charmingly described in the diary of the community:

At the end of this month the congregation of Salem had the pleasure of welcoming the President of the United States, on his return journey from the Southern States. We had already heard that he would return to Virginia by way of our town. This afternoon we heard that this morning he left Salisbury, thirty-five miles from here, so the brethren Marshall, Koehler and Benzien rode out a bit to meet him, and as he approached the town several melodies were played, partly by trumpets and French horns, partly by trombones. He was accompanied only by his Secretary, Major Jackson, and the necessary servants. On alighting from the carriage he greeted the bystanders in friendly fashion, and was particularly pleasant to the children gathered there. Then he conversed on various subjects with the brethren who conducted him to the room prepared for him. At first he said that he must go on the next morning, but when he learned that the Governor of our State would like to meet him here the following day he said he would rest here one day. He told our musicians that he would enjoy some music with his evening meal, and was served with it.

When Gov. Alexander Martin arrived, Washington talked with him about the attitude of the people to the new government. Martin confirmed for his own State all that Colonel Carrington had said of public sentiment in Virginia: opposition and discontent were subsiding fast.

In the company of the suave, conciliatory Governor, Washington rode on June 2 to Guilford, where he examined the ground of the engagement of March 15, 1781, between Greene and Cornwallis and concluded that “had the troops done their duty properly, the British must have been sorely galled in their advance, if not defeated.” The day after surveying the scene of a tactical defeat that became a strategical victory, Washington bade farewell to Martin and started on the final stage of his journey, a stage broken by no ceremonial of any sort.

From Guilford the President rode to Dan River, and on to Col. Isaac Coles’s plantation on Staunton River, whence in a single day he proceeded to Prince Edward Court House. By the afternoon of the tenth he was at Kenmore, his sister’s home in Fredericksburg, and on June 12 he ate dinner at his own table in satisfaction over the accuracy of his timing and the sturdiness of his team. He wrote with enthusiasm of the journey:

. . . it has enabled me to see with my own eyes the situation of the country through which we traveled, and to learn more accurately the disposition of the people than I could have done by any information. The country appears to be in a very improving state, and industry and frugality are becoming much more fashionable than they have hitherto been there. Tranquility reigns among the people, with that disposition towards the general government which is likely to preserve it. They begin to feel the good effects of equal laws and equal protection. The farmer finds a ready market for his produce, and the merchant calculates with more certainty on his payments.

The journey had shown that the President was as popular in the Southern States as he was in Federalist New England. On the tour he received at least twenty-three addresses, in answering which both he and Major Jackson well might have spent their stock of friendly phrases. Particularly noticeable were the addresses from Lodges of Free Masons. This probably had no significance other than as it disclosed the strength of the Masons in the South and their pride in Washington as a brother. His answers, in turn, were in good Masonic terms, with no casualness in his references to his membership in the Order. Washington himself perhaps was unaware of it, but he was becoming increasingly fond of the homage paid him at assemblies and wherever he made his bow to ladies. Mounted escorts that deepened mud or raised dust were a nuisance, but ladies, handsome, well-dressed ladies who paid him the honor of calling on him . . . well, the Presidency was not altogether without its compensations.

Washington had transacted little public business on his tour, and he found a heavy accumulation of papers at Mount Vernon. He encountered, besides, a multitude of plantation duties, sadly increased by the progressive illness of George Augustine. Some problems of domestic management at the house in Philadelphia were posed also, in reports from that city.

A drought had ruined the hay crop and now threatened the oats; but Washington faced his labors with his usual, well-ordered self-discipline and made the most of the fortnight at home before he started for Philadelphia on June 27 by an unfamiliar route. First he went to Georgetown and there had the pleasure of announcing where the public buildings would be located, though, by this time the President was beginning to divest himself of responsibility for the proposed seat of government and passing on the details to Jefferson. Then he proceeded, via Frederick, Maryland, to York and Lancaster, Pennsylvania, two towns he never had visited.

The week following Washington’s return to Philadelphia on July 6 brought a minor illness and a move by Pennsylvania politicians to construct a new house for the President—an involvement he avoided with some difficulty. These were mere annoyances, though, compared with ominous increase of tension among European countries. The three powers that appeared to be on the verge of renewed conflict happened to be those whose holdings in the northern hemisphere were adjacent to the United States and constituted either a market or a threat or both. England still was in possession of northwestern posts and was suspected of inspiring Indian raids. Spain’s hold on the Mississippi and her occupation of New Orleans and Florida gave her a position as formidable as that of the British in Canada. France was in convulsion at home and was facing a frightful slave insurrection in Santo Domingo, her richest West Indian possession.

War among these powers might be ruinous to American foreign trade. Even the possibility of a coalition between Britain and Spain, with France as their common adversary, would expose all three of the land frontiers of the United States to danger at the same time that it might involve a call by France for America to fulfill the military alliance of 1778. These were contingencies Washington faced without self-deception and with little or no prejudice. Towards them he applied certain clear principles. Efforts must be made to effect peace with the Indians by formal treaties that acknowledged the natives’ territorial rights and assured American recognition of them, and Indians who chose war instead of peace were to be punished with vigor and severity; so young and weak a republic as America must keep out of foreign wars if this could be done with honor and self-respect; achievement of peace depended on drawing a distinction between conflicts with foreign interests in America and American interference in Europe; balanced policy had to be pursued separately and patiently with each of the three powers. Methods might be different; the basis of bargaining might be shifted; the goal was the same—peace, progress and the deserved larger respect of European countries.

In applying these broad rules to Britain, Washington could not disregard the feelings of his fellow countrymen who were resisting what he believed to be the general desire of peace. Something had to be conceded to the old American resentment. Said Washington:

There are . . . bounds to the spirit of forbearance which ought not to be exceeded. Events may occur which demand a departure from it. But if extremities are at any time to ensue, it is of the utmost consequence that they should be the result of a deliberate plan, not of an accidental collision; and that they should appear both at home and abroad to have flowed either from a necessity which left no alternative, or from a combination of advantageous circumstances which left no doubt of the expediency of hazarding them. Under the impression of this opinion and supposing that the event which is apprehended should be realized, it is my desire that no hostile measure be in the first instance attempted.

An understanding with Spain manifestly was difficult: Obscurity surrounded the designs of Gov. Estéban Rodriguez Miró. Dr. James O’Fallon, perhaps the most active of the frontier adventurers at this time, had been operating for the South Carolina Yazoo Company and had been loud in his professions of loyalty to the United States; but there had been suspicion that he planned to seize a region that had been acknowledged by the American government to be an Indian possession. Concern had been felt that this man might precipitate a frontier war and even might involve the country in hostilities with Spain. A proclamation against O’Fallon’s activities and an order for his arrest seemed enough in the spring of 1791. Thereafter Washington gave first place in Spanish negotiations to the removal of the suspicion that the young Western Republic was eyeing covetously the Spanish West Indies.

Washington continued to follow the progress of the Revolution in France with sharpest interest, but he confessed his anxiety regarding “indiscriminate violence” from the “tumultuous populace of large cities.” He wrote to the Marquis de la Luzerne:

. . . however gloomy the face of things may at this time appear in France, yet we will not despair of seeing tranquility again restored; and we cannot help looking forward with a lively wish to the period when order shall be established by a government respectfully energetic and founded on the broad basis of liberality and the rights of man, which will make millions happy and place your nation in the rank which she ought to hold.

Patience was needed if this was to be achieved, and patience America had to display in dealing with abrupt changes of policy under the revolutionary government. The new French Minister to the United States, Jean Baptiste Ternant, was received cordially and with personal consideration. The utmost was to be done in complying with a French request for money and arms to combat the slave insurrection in Santo Domingo. No advantage was to be taken of France by repaying the American debt in depreciated assignats. Friendliness was shown in the rejection of a dubious refunding plan submitted by European speculators.

Such was the simple, prudent foreign policy Washington adopted on his return to Philadelphia. It was a policy that had to be applied as opportunity offered, with respect to Britain and Spain, but it was imperative and immediate where Santo Domingo was concerned. Moreover, charges of British incitation of Indian warfare were about to be put to test. The Commander-in-Chief knew St. Clair had no experience in this type of warfare and repeated the warning he so often had given officers entrusted with troops in the wilderness: Beware of surprise. St. Clair at the proper time, presented a plan for establishing a military post at the so-called “Miami Village” as a means of over-awing nearby Indian tribes and showing the British that the United States had no intention of abandoning that rich area to the King. The proposal was thought a good one and was taken up and entrusted to St. Clair, who was recommissioned at his wartime rank of Major General. His instructions were “to establish a strong and permanent military post” and, after garrisoning it adequately, “seek the enemy” and “endeavor by all possible means to strike them with great severity.”

Determination of main lines of policy did not require many days, nor did Washington have to sit long at his desk in preparing notes for his message to Congress which, according to his calendar of events, was to assemble on October 31. Details were put aside for leisured review at Mount Vernon, whither the President turned his carriage again on September 15. This time, the reason was necessity: George Augustine Washington, in a pathetic condition—had gone to Berkeley Springs in the hope of regaining strength. The owner of Mount Vernon had to make arrangements for operating the estate during his nephew’s absence. The General reached home on September 20 and commenced a survey of his affairs. His most important task after a deathly dry summer was instructing Anthony Whiting, who had succeeded Bloxham as his head farmer, in management of the property; but, as always, scores of lesser matters awaited his decision. In addition Washington had considerable correspondence with officials in Philadelphia and continued to direct the preparation of material for his address to Congress. Everything seemed to be in smooth progression, when, from a letter received October 13, Washington discovered that he had made a mistake concerning the date of the meeting of Congress: it was to assemble on the twenty-fourth, not on the thirty-first. No time was lost after that. Word was sent to Philadelphia for speed in collecting the information he would require.

Washington’s address on the twenty-fifth had a cheerful opening and prime emphasis on operations against the western Indians, but it contained no important suggestion on new legislation other than that the law imposing an excise on spirits be revised where valid objection was disclosed. Most of the later paragraphs dealt with recommendations previously made and not yet enacted. Congress’s response was one of unenthusiastic approval that slowly shaped itself into bills considered in leisured debate. Gradually, there developed a new vigor of dispute and a closer approach to rival philosophies, but the antagonisms of large States and small, Eastern interests and Southern, prevailed on occasion over the abstract question of the scope of Federal power.

Washington had to remain in Philadelphia throughout a session that proved inordinately long. Time-consuming was the President’s continuing responsibility for the District of Columbia, though he used the services of Jefferson as far as practicable and insisted officials and employees under the District commissioners report through them. When the principal surveyor, Major L’Enfant, quarreled with the men to whom he was responsible, Washington tried several devices to retain the services of the brilliant designer but came to the conclusion that L’Enfant could not work in harness. Dismissal of the engineer was distressing, but no alternative existed.

Another continuing labor was presented by the ominous decline in the health of George Augustine. Fortunately, Whiting seemed to possess both intelligence and industry and took ever an increasing share of the work on the estate. During the autumn, because of Congress, L’Enfant and Mount Vernon, Washington had a heavy load but he carried it without getting—to use his own words—“on a stretch.” October brought a development in relations with England: a British Minister, George Hammond, the first diplomatic agent to be accredited formally to America, arrived in Philadelphia to take up his residence there. As soon as practicable, Washington selected Thomas Pinckney, of South Carolina, for the corresponding post at the Court of St. James’s.

No question so frequently was discussed at the President’s conference with his heads of departments as that of relations with the Indians. Almost every informed public servant in the United States believed a settlement with Britain would put an end to most of the murderous raids along the Ohio and its tributaries. Peace with the Creeks would be easy when Spain no longer supplied them with powder and arms. Meantime, Washington continued to work for amity with well disposed tribes and for victory over the coalition against which St. Clair had been dispatched.

On December 8 unofficial reports were received in Philadelphia of a costly defeat sustained by St. Clair within fifteen miles of the Miami town where he was to establish a post. It was said that his casualties reached no less than six hundred and that Gen. Richard Butler and other senior officers were among the slain. The next evening, Washington received dispatches from St. Clair that included words to make the President set his jaw: “Yesterday afternoon, the remains of the army under my command got back to this place, and I now have the painful task to give you an account of as warm and as unfortunate an action as almost any that has been fought, in which every corps was engaged and worsted, except the First Regiment. That had been detached. . . .” St. Clair had been warned against surprise, yet he had permitted the Indians to gain overpowering advantage almost before the alarm could be sounded!

Washington, on reading St. Clair’s report, could not have overlooked a postscript in which the ill-faring commander remarked that “some very material intelligence” had been communicated by Capt. Jacob Slough to General Butler during the night before the action but was not forwarded to St. Clair or known to him for days. A man less self-mastered than Washington might have winced at that, because he had appointed Butler to command in the face of protests. Good soldier or poor, vigilant or forgetful, Butler was dead and, with him, thirty-eight other officers. Twenty-one who held commissions were wounded. Casualties exceeded nine hundred. All the cannon with the main force had been lost. The “most disgraceful part of the business,” said St. Clair, “is that the greatest part of the men threw away their arms and accoutrements, even after the pursuit . . . had ceased.” Nothing so humiliating to the white man had been experienced in Indian warfare since Braddock’s bewildered Redcoats had been the target of unseen marksmen on the Monongahela.