5

Managerial Approaches and Theories of the Firm

Over the last two decades, complex systems have drawn the attention of numerous researchers from different disciplines. Allen et al. (2011, p. 2) remind us precisely that complexity cannot be studied in a monodisciplinary framework. Each discipline offers its own methods, approaches and measures, and all converge towards common definitions. Rarely can one find fields of transdisciplinary research where the advances in one domain (e.g. cybernetics) are considered by another discipline (e.g. philosophy) to then inspire the practices of a third (e.g. management) with considerable transparency and respect between the various disciplines. It is true that no discipline can claim to have an answer to every question related to complexity, which obligates a rather rare sort of mutual respect upon authors.

A complex system is made up of interacting parts forming a “whole”. Each of these parts is governed by a set of rules, routines or forces that determine their behavior at a given moment based on the state and behavior of other parts. The interactions between the parts are generally numerous, dense and not necessarily limited in terms of location. These interactions may be formal, informal, virtual or suffused with materiality. Each part reacts according to its own stimuli on local or global emergent phenomena, even in the absence of coordination between the parts. However, the results of these interactions are difficult to foresee, even if abundant knowledge on the parts and the interaction rules is available, for there are many independent causal links. The system’s “complexity” manifests itself through the issue of phenomena that affect all or part of the system with a regularity that is neither static nor random, but difficult to describe precisely and exhaustively.

Works on complexity in economics and management aim to study complex systems, their appearance and their evolution. These works are sometimes highly quantitative (use of mathematical modeling or computer tools) and sometimes qualitative (case studies, analogies, longitudinal studies).

The hierarchic view of economic systems as complex adaptive systems in a state of constant evolution owes a great deal to the precursory works of Nelson and Winter (1982). At their instigation, management of a firm and economics have shifted from a situation with absolute, quasi-Newtonian rules on steering organizations to situations where decision makers’ knowledge is limited in an ever evolving environment with rules that are themselves undergoing change.

No manager faces an environment where the rules never change. We are able to describe the organizational dynamics of numerous economic and social systems primarily based on our own experience, and it is highly likely that another person’s perception of these dynamics and its interpretation would be different. These differences in perception paired with other goals and constraints lead to divergent behavior that will either reinforce one another or come into conflict, and thus influence the overall dynamics of the system.

Although it is possible to predict the evolution of the system to some extent, under a given set of conditions, small-range and a priori inconsequential local events disturb and modify the system as a whole in the long-run. The science of complexity offers a framework for accepting two situations, i.e. individuals are neither omnipotent nor significant. They are certainly not capable of modifying a system as they please, but their role is not insignificant either. They can change the system through their actions if they take on the system’s complexity readily rather than rejecting or fighting it. Based on this fact, studies on complexity as well as those on creativity use dynamic approaches rather than visions of static equilibrium. Dynamics do not follow fixed rules or new qualitative elements; random variations show up as other elements fade away. In fact, complexity is a science for any organization, and research on creativity studies the indications of (sometimes weak) signals causing the system’s evolution. Creativity thus is an aspect that exists both in entities (individual creativity) and the system as a whole (organizational creativity).

In section 5.1, we will provide a non-exhaustive list of works in management, grouped conforming to broader functions (strategy, information system, etc.), explicitly referring to complex systems, chaos theory, etc. In section 5.2, we will return to a conceptual model that enables us to distinguish between concrete actions and different positions to be assumed by a manager when faced with a complex system. The following sections will focus on two specific managerial functions: marketing (and its strong connection with strategy) and human resource management.

Indeed, the place of marketing in a complex adaptive system is less apparent initially. Wollin and Perry (2004) have a rather clever approach to this relationship, recalling that the theory of complexity enables marketers to understand a market’s function. Complexity provides global and local explanations for markets and complements other theories such as relational marketing. By employing the Honda case, Wollin and Perry illustrate the extent to which complex systems can be employed in strategic marketing. Colbert uses an approach, connected with theories of the firm, to indicate through an example of human resource management how a conceptual approach far from the field can enlighten managers.

5.1. Complexity and management: the first steps

The use of complexity science to represent and create economic models sharply contrasts with classical approaches. Nevertheless, attempts have been made previously to describe the operations of organizations under different names such as the systems approach, the holistic approach and the systemic approach. Systems theoreticians dominated the study of organizations during the first half of the last century. Since 1938, organizations have been represented as multiple units of cooperation thanks to Bamard. These cooperations are then the engine of creation for new properties both between and internal to organizations. These properties are qualitatively different from previous ones and distinct from the qualities of the organization’s members (Reed 1985). This work has progressed from the study of the internal organization of systems to the study of open systems (Scott and Davis 2007) and more recently open strategies (Hautz et al. 2017).

Following Bamard’s works, numerous authors have contributed to the development of a generalized systems theory. In particular, we can cite Boulding (1956) and von Bertalanffy (1968), who presented the framework for the study of systems, to which many subsequent authors made a significant contribution. Among these was Ashby (1956) and his law of requisite variety, or Simon (1982) who described complexity science based on his work on decision-making in specific organizations, a study that he conducted notably through the use of digital tools to represent interactions and decision-making. At that time, Thompson (1967), as one of the founding fathers of contingency theory, also contributed to the emerging study of systems. Indeed, contingency and complexity both share the need to describe structures and relationships with the environment (Anderson 1999).

Table 5.1 provides an overview of these works. Even if all of the references emphasize the implications of complex systems for managerial issues, there are few references that explain the behavior that managers must adopt.

Table 5.1. The first research on management in connection with complexity (source: Maguire et al. 2011, document updated by the authors)

Implication for… |

Introduction of… |

References |

Management of natural resources |

Modeling evolutionary systems |

Allen and McGlade (1987); van Mil et al. (2014) |

Public administration |

Absence of equilibrium, Chaos theory |

Kiel (1989); Gerrits and Marks (2015); Daneke (1990); Overman (1996) |

Social sciences, Social science research methods |

Nonlinearity, Chaos theory |

Kiel (1991); Smith (1995); Gregersen and Sailer (1993); Reed and Harvey (1992) |

Management |

Complexity theory |

March (1991); Lissack (1997); Johnson and Burton (1994); Glass (1996) |

R&D management and information systems |

Chaos theory |

Hung and Tu (2011); McBride (2005) |

Strategy |

Chaos theory, Complexity theory |

Levy (1994); Stacey (1993); McMillan and Carlisle (2007) |

Quality management |

Complexity theory |

Dooley et al. (1995) |

Leadership |

Complexity theory |

Stumpf (1995); Wheatley (2006); McDaniel (1997) |

Organization theory |

Self-organization of systems, Chaos theory, Complexity theory |

Thiétart and Forgues (1995, 2006); Drazin and Sandelands (1992); Niang and Yong (2014); Anderson (1999); Morel and Ramanujam (1999); Burnes (2005); Begun (1994); Cottam et al. (2015); Zuijderhoudt (1990) |

Healthcare service management |

Complexity theory |

Resnicow and Page (2008); Arndt and Bigelow (2000) |

Human resource management |

Complexity theory |

Colbert (2004) |

Marketing |

Complexity theory |

Smith (2002); Wollin and Perry (2004); Hibbert and Wilkinson (1994); Nilson (1995) |

Entrepreneurship |

Chaos theory |

Han and McKelvey (2016); Smilor and Feeser (1991); Mason (2006) |

Project management |

Chaos theory |

Simard et al. (2018); Priesmeyer and Baik (1989) |

Internationalization |

Nonlinear phenomena, Complexity theory |

Mendenhall et al. (1998); Chandra and Wilkinson (2017) |

5.2. Manager’s role versus complex systems

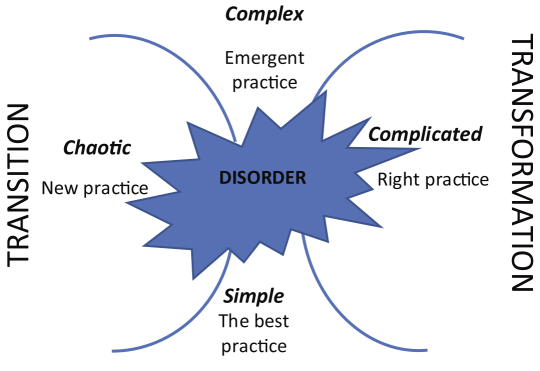

The manager’s role is to analyze and characterize the organization’s environment and its situation, and then provide a suitable response. In this regard Snowden and Boone (2007) perfected an analysis tool to improve decision-making: the Cynefin model, which helps in decision-making based on the environment. It is the manager’s job to adapt his or her behavior to the present environment. The authors have identified four distinct environments (Figure 5.1):

- 1) If the environment is simple, the relationships between causes (A) and effects (B) are clear; and if the manager decides A, B will always take place. The organization responds to the situation through routine behaviors at its disposal in its process repertoire. This environment is not necessarily the most comfortable, for even if the manager’s involvement is minimal in this situation and limited to a control mission, this can be a source of lost vigilance for him or her and all collaborators. The standard responses provided can lose their effectiveness without this necessarily being noticed and the firm can get stuck in a simple learning loop.

- 2) If the environment is complicated, the manager identifies what is unknown. Cause-effect relationships are acceptable and the manager’s role is “simply” to pinpoint the usual system response that is best suited to the situation. The work put upon him or her is similar to that of surgeons or engineers. It is meaningless to invent new procedures, solutions or treatments; it is enough just to collect elements from the environment to determine the right behavior by lifting the veil off the unknowns.

- 3) In a complex environment, the manager must adopt the given solution or even devise a new one. This is the case in many economic situations, whether this involves competing markets or competition within an organization for a promotion. There are many unknowns and a real need arises to adapt a solution. For an example a firm must adapt its products to the customers’ desires while setting itself apart from the competition, i.e. the solution must then be unique.

- 4) In a chaotic environment, cause-effect relationships quite differ and are often vague. The manager must test the environment anyway before adapting a response. This represents the only method one can adopt for obtaining new information that is somewhat reliable. Without seeking to establish causal relationships or a battery of organizational responses, it is the manager’s job to find out promptly what works least. Next, corrective actions can be taken to improve the situation.

Figure 5.1. The four situations from the Cynefin model (source: Burger-Helmchen and Raedersdorf 2018). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/heraud/creative.zip

To illustrate this representation, let us take the case of a supervisor managing two lines of products. The first product is at the final stage of its life cycle, where its market has already reached the peak of maturity, and competitors are gradually withdrawing from this market. The environment is simple. The collaborators provide standard responses to the day-to-day problems and the supervisor must spend most of their time managing the lessening activity. For the second line, a future flagship product, an equivalent inverse problem exists. Even if the supervisor has already launched multiple products onto the market, things are different, particularly if the product is launched into several (developed and emergent) markets at one time and unexpected competitors appear at the last moment. Moreover, some collaborators associated with the product are new and the supervisor is unaware of their reactions. In this chaotic environment, it is preferable to test the reactions of the collaborators and the competitors on the new markets before deciding on a definitive strategy.

As noted by Burger-Helmchen and Raedersdorf (2018), complicated and chaotic environments do not maintain historic cause-effect relationships and new logical sequences are not immediately apparent. In these environments, the manager’s role is to test the waters if the environment is complex or act if the environment is chaotic before formulating an adequate response. Not taking any steps for providing better solution does quite the opposite. Likewise, when the organization has to innovate in a chaotic environment, it is better to accept provisional situations and imperfect solutions, even if it means having to improve them later.

Based on this generic framework for managers, we will now see how researchers have adapted the logic of complex systems to their field of specialization, turning our sights first on marketing and then on human resources.

5.3. Marketing and complex systems

Marketing, as we are reminded by Kotler and Keller (2015), is a planning and execution process that includes product design, price, promotion and the distribution of goods, ideas and services, all with an aim to create satisfactory exchanges for the consumer and to meet the organization’s goals. These processes are often represented by 4P or 4C models in their modern vision (Burger-Helmchen and Raedersdorf 2018).

Due to consideration of communities and the development of social networks, numerous marketing authors over the past 20 years have turned their attention to the repetition of exchanges rather than a single transaction. Marketing offers a renewed sense of belonging to a community. This “belonging” makes relationships less fleeting, creates interaction dynamics between different agents forming a system with timeless properties: the transactions of yesterday establish the conditions for the transactions today, which will in turn define the exchange rules of tomorrow. This temporal contingency lies at the heart of complex systems and chaos theory.

Very few works in marketing explore this type of contingency (see Table 5.1). Following strategic management, the dominating model is that of punctuated equilibrium. This model presents the normal evolution of an organization as a series of incremental improvements whose impact is marginal and do not affect the large equilibriums in place. The breakthroughs – major changes – that affect an organization and influence the system as a whole are rather infrequent (and, depending on the model, may or may not be foreseeable). Among the notable exceptions are Hibbert and Wilkinson (1994), who use a specific case to illustrate the evolution of a system in connection with marketing. Nilson (1995) identifies nonlinear marketing relationships between the product and consumers’ opinions.

Wollin and Perry (2004, p. 557) explain this low number of works concerning “marketing and complex systems” as a result of the difficulty faced by authors in exploring the generalist previsions of complex models in their enterprises. Followers of complex systems have formulated few convincing responses to the question, “If you are globally smart, why aren’t you locally rich?” In reality, the difficulty faced by certain researchers in management science, who use complex models to justify the relevance of their works, precisely lies in their scarcity. Indeed, success of complex systems lies in the field of life sciences, physics and meteorology because there are many works that accumulate to reinforce and complement one another, yet the social sciences face more intense problems in contingencies – ones that are more difficult to model – which makes the progression of knowledge slower. Particularly in complex systems in the social sciences, individuals learn, anticipate and modify their behavior. In complex systems applied to meteorology, for example, this is, however, not the case (Lorenz 1963). It is not possible to express this with equations containing constants. Throughout this section, which is dedicated to marketing, we try to show how the representation of a market in the form of a complex system is elucidating for a marketer. In general, four types of representations of complex adaptive systems can be used in management science. The complex adaptive systems model is probably the most appropriate to represent the interactions between the market and the marketing process. We then use the example of Honda developed by Wollin and Perry (2004) to show how consideration of contingencies, feedback loops and path dependence makes projection and control difficult (and crucial) for marketers.

5.3.1. Hypotheses and theories of complex systems

Gleick’s image (2008) of a butterfly flapping its wings on one continent and hurricanes appearing on another has become the symbol of chaos theory. The identification of regularities in an apparently random whole is the objective of those who observe complex systems. Such regularities (and contingencies) have been grouped into four sets of hypotheses in management science.

- 1) Entreprises (and marketers) have different forms of micro-diversity, i.e. they differ from others in certain aspects but are similar in others. All of the similarities (e.g. mastery of a certain technology or recourse to the same supplier) is called macro-uniformity. Differences can be found in the micro-foundations of each firm.

- 2) The behavior of each firm (or each head of marketing) is subject to different degrees of path dependence, i.e. each will be more or less influenced by its own personal history. The dynamics of decisions on the market, in a system, depend on this history, which constitutes the starting conditions.

- 3) The distribution of behavior can change drastically in a short time. Thus, if usual behavior respects the distribution of a normal law most of the time, “creative” or unusual behavior sometime appears. This behavior is likely to modify the systems’ properties. The smaller the number of firms or heads of marketing is within a system, the greater the impact of creative behavior may be.

- 4) Not all rules evolve at the same rate. Some behavior rules only change slowly, for they correspond to the profound culture of an organization, or they exist as a function of the interactions with other actors in the system (a sort of common code). Others are likely to be modified much more quickly by the effect of learning and exogenous shocks, or more likely in the case of marketing by the desire of an actor to change the code in place.

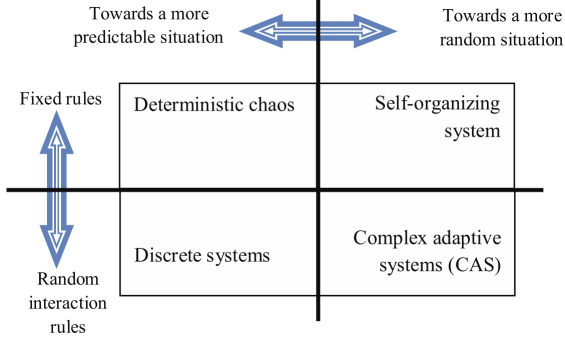

Of these four points, the first two being micro-diversity and path dependence characterize the local context (the firm) in which the marketer must act. The following two enable us to define a space to represent four types of complex systems corresponding to the (in)consistency of interaction rules and the normality/creativity of behavior.

5.3.2. Four types of complex systems

The first type of complex system corresponds to deterministic chaos. “Deterministic chaos” is an oxymoron that reflects the paradox of coexisting order and disorder within a single system. Meteorological phenomena or earthquakes typically belong to this category. Stabilizing forces and disturbances come into conflict, the system sometimes swinging to the extremes. These antagonistic forces make the system more difficult to predict. However, such systems can be modeled, mathematically described, provided that they are rather simple and only include a few variables. Nevertheless, most social systems include a large number of interacting variables. The hypothesis that interaction rules are constant does not apply to marketing. Managers learn from their interactions with clients, suppliers and competitors. The model created by Argyris and Schön (1978) lines up with this situation where consideration of new elements leads to an adaptation/evolution of the rules. As a result, the markets are more complex than deterministic chaotic systems.

This framework has been used in management to metaphorically describe the cycling phases of stability and instability in social systems, firms or project management (Brown and Eisenhardt 1998; Wheatley 2006). Another application in management lies in the creation of data for comparison (Hibbert and Wilkinson 1994; Cheng and Van de Ven 1996; Glée-Vermande 2016).

Figure 5.2. Four types of complex systems in marketing (source: Wollin and Perry 2004). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/heraud/creative.zip

The second type is a self-organizing system where order emerges from apparent disorder. A process involved in these systems leads elements to cooperate, coordinate and demonstrate united behavior, a priori spontaneously (Stacey 2010). These systems have micro-behaviors that do not dissipate into general behavior; on the contrary, it is a harbinger of change. The result is not predictable, for not all the interaction rules are known and many are emergent. Social systems do not have a limited number of convergence points, and self-organization models are not countable. Thus, a marketing situation is only partially represented by this type of complex system.

Another type of such system is based on hypotheses that are more appropriate for marketing (the fourth type is a version with discrete and thus less realistic states).

This third type, complex adaptive systems (CAS), found in the bottom right corner of Figure 5.2, is characterized by the ability of actors to profoundly change the system in which they evolve and interact. Complex adaptive systems take shape in markets where adaptation is possible (Simon 1945). This kind of market is made up of a large number of consumers and interdependent firms. Each of these actors interacts with many other actors as well as the environment in general. The fact that the market is made up of a large number of actors must not lead us to a view that this situation is comparable to that of a pure competition market and is an attempt to perfect the neoclassical model. Indeed, it is notable that this final model formulates hypotheses of perfect information and agent homogeneity; however, in the present case, we are far removed from this theoretical account, because firms and consumers each have their own history. Moreover, the products and services are not homogeneous (hence the interest in marketing campaigns) and nothing guarantees individuality in pricing. The order that will be established within the system is not determined ex ante.

If there is balance, which is not guaranteed, it can be modified by interactions within the system according to the mechanism described by Adam Smith (1776). Mechanisms for adapting to each external or internal shock act as an “invisible hand”. This adaptation affects the behavior of the actors and even the rules that are in effect within the system. In fact, these systems are potentially robust and sustainable because they are both capable of changing their environment and adapting to environmental change.

According to Simon (1982), these models are particularly relevant for the study of markets, for they use an architecture of multi-level rules; in other words, there are rules on a higher level (e.g. the system level) and a set of rules at other lower levels (for a firm, a project, a transaction, etc.). For Simon, a change to a higher-level rule leads to chain adaptations in the lower-level rules. However, evolutions in micro-level rules do not lead to modifications in higher-level rules (or do so in a less automatic way). This one-directional interaction between the levels broadly contributes to its stability. This structuring of the rules owes itself to the organizations’ beliefs, values, culture and routines (Gersick 1991; Cohendet and Llerena 2003). For a firm, this structuring stems from its history, experience gathered through past interactions with consumers and competing firms. Higher-level variations come about less frequently, whereas those at a lower level appear at a higher rate.

These models, as we emphasized in Chapter 1, hold positions similar to evolutionary models of the firm. The evolution of the rules takes place through processes of variation, selection and retention (Nelson and Winter 1982; Carroll 1984). This succession of stages, the source of positive feedback loops (the source of new change) or negative ones that freeze the system for a certain period of time, allows innovations and imitations to take place (Stacey 1991).

Thus, for Spender (1989, 2015), the study of a market from the perspective of complex adaptive systems implies i) the search for specific rules and the ordering of these rules; ii) the examination of causes leading to the evolution of rules and iii) the identification of structures and behavior common to the primary actors in the system.

The last situation described in Figure 5.2 is a discrete vision of markets. The actors all line up with a median behavior. However, the model can swing towards another state, a new equilibrium, where the actors all act once again in a standard way based on the new state of the system. This situation is often described as a – discrete – subset of the complex adaptive systems, which offer broader behavior spectrums (Gersick 1991).

5.3.3. Honda and the global automobile market

To illustrate the marketing approach to complex systems, auto manufacturer Honda serves as a good example. Wollin and Perry (2004) analyzed this case that, in their opinion, illustrates how a firm adapts to complex systems. Indeed, the automobile market is a relatively open global market with a large number of interacting agents (large purchaser firms, manufacturers of numerous parts, consumers and multiple commercial intermediaries). This industry regularly undergoes cycles of profound transformation: the introduction of mass production (1920), the development of European manufacturing (1950), the growth of Japanese manufacturers (1970), intensified collaboration (1990) and the development of electric vehicles (2010), to name a few. This reinforces industry’s internationalization at each step (Jones 1985; Amatucci and Mariotto 2012).

Honda played a special role in building the ties between the United States and Japan in the late 1970s and 1980s. This firm also has witnessed marked growth and strategic variation since the 1990s.

5.3.3.1. Micro-diversity within the firm and the sector

The global automobile market is characterized by macro-uniformity. There are in fact many characteristics common to all manufacturers; and vehicles around the world have too many points in common (number of wheels, seats, etc.). Consumers expect vehicles to be equipped with more options in pricing terms. However, we observe great micro-diversity. Thus, the distribution of parts on the market varies from one country to another; the same brands are to some extent not available elsewhere. Firms choose to produce a complete or partial range of products, to offer a variety of options and complementary services. Not all management methods are identical, nor are the choices for the geographic distribution of factories.

Not all firms have the same micro-foundations, either (Augier and Teece 2008). We can therefore conclude that this market proves the hypothesis of micro-diversity in complex systems.

5.3.3.2. Irreversibility and path dependence

The second characteristic that we can attribute to this sector matching the description of a complex system is path dependence. Future behavior is influenced by the actors’ history (Arthur 2014). This path dependence can be more or less pronounced depending on the systems and actors (Cowan and Hultén 1996).

Honda started manufacturing cars in the mid-1960s, after establishing their leadership on the motorcycle market. This late entry onto the automobile market was initially a disadvantage for Honda, which had held a very modest position in Japan for nearly 20 years. Honda long held fifth place in terms of market share in its country of origin, partly because of its adverse location in Japan. However, Honda was the first Asian manufacturer to build a factory in the United States.

In the United States, Honda was less constrained by path dependence, as there was a lesser degree of social and cultural rigidity there. The primary competitors in the United States suffered the same problems that Honda has experienced in Japan. Unlike large American manufacturers, Honda, with its new factory in Ohio, had no long-term agreements with unions or suppliers. Honda also had not made irreversible investments in production goods. American manufacturers had problems shifting production to bring out more compact vehicles as they hoped to first make profits on the investments made on existing production lines which otherwise seemed to be irrecuperable costs to them (Besanko et al. 2017). Thanks to this favorable strategic position, Honda began manufacturing and commercializing the Accord in the United States where it remained the most sold vehicle in its category for more than 20 years.

The automobile market belongs to a set of industries in which the weight of investments to innovate and commercialize innovations is so great that it imposes a timeframe on global system evolution. Firms in this sector have long succeeded in developing thanks to their massive investment in productive capital rather than in R&D. This phenomenon was particularly pronounced in the United States after World War II, when technological innovation in manufacturing processes and vehicles present were comparatively much less than economies of scale linked to modifications in manufacturing.

Honda, unlike American manufacturers, established multi-product production lines very early to enable the production of vehicles such as the Accord or the Civic. It demonstrates that the complex system of auto manufacturers, in which Honda finds itself, is sensitive to initial conditions of operation and presents a certain degree of path dependence.

5.3.3.3. Variety of results

A third characteristic of complex adaptive systems is the variety of results obtained by different actors. There is simultaneously a group presenting average results including actors performing at a higher or lower level.

These variations in performance within a complex system, such as the automobile sector, are caused by several elements. First, the market in question is not in a state of pure, perfect competition, but in a state of oligopoly. Thus, it is possible for the actions of a small number of firms to noticeably change the median result. This play between the results of average and median creates particular industrial dynamics.

Next, there are positive and negative feedback loops within this market. Thus, the fact that Honda established itself in the United States initially had a positive effect leading the entire group to evolve, to change certain practices and to some extent its culture. However, the great success experienced by Honda thereupon generated a negative feedback loop too. Actually, considering the size of the market in North America, Honda began focusing its vehicle design on the tastes of North American consumers, yet the specificities of the vehicles desired by these consumers differ greatly from those of Japanese consumers. For a while, Honda established the design including some of its rules primarily for the American market but failed to develop satisfactorily on the Japanese market.

Finally, different results produced imply no occurrence of coevolution between the general system and all the firms. Indeed, some firms will evolve faster than others. For Stacey (1993), this situation of partial coevolution is a supplemental factor that makes the system’s global evolution harder to predict. This is also the case of differential in coevolutions that supports heterogeneity within the system.

Honda won shares on the American market because the firm rapidly evolved towards the production of compact vehicles. Many manufacturers took time to enter this market segment, long considered to be a small niche of little interest to the giant industries in Detroit. However, successful coevolution does not indicate capability to repeat the operation and always perfectly stick to the market. Thus, Honda was ahead in certain aspects, but took longer to begin manufacturing four-wheel drive vehicles. Other Japanese competitors such as Toyota and Mitsubishi were able to take advantage of this market segment’s growth.

5.3.3.4. Evolution of interaction rules

In a complex system, firms do not have constant interaction rules with one another nor with other elements in their environment. It is therefore necessary to question the factors bringing change to these rules and the factors that are likely to create resistance to change.

The points that we highlighted in the preceding sections illustrate the evolution of interaction rules. Indeed, actor micro-diversity leads to a need to adapt the interaction rules of the actors on the same level. Thus, introducing a radically new vehicle, that creates a previously unseen market sector, forces competitors to become followers, imitating the predecessor. This was the case in France with the release of the Twingo, which changed consumer and manufacturer interest in small vehicles (interest that had been lost since the end of models such as the R4, R5, 2CV, 104, etc.). The interaction rules also change based on external shocks. Thus, in the late 1990s, when the Japanese market suffered its first significant slowdown, manufacturers felt threatened. This was notably true for Mazda and Nissan. Nissan underwent a clear change in its interaction rules within the scope of its alliance with Renault.

Finally, the firm may determine the evolution of interaction rules with the environment. This was the case when Honda decided to deliberately enter the North Korean market, drastically changing the actors with which it interacted.

In the early 2000s, Honda faced many challenges. The new manager saw no need to change some of the lower-level rules but to modify the higher-level rules that would themselves lead to changes at the micro level. In particular, the company was reproached for following its founder’s logic. Engineers were in charge of everything and little room was made for marketing and interaction with clients. The release of the Accord was less to satisfy clearly identified customer needs and more to show off the engineers’ technical exploits: attempting to bring together all the options in a smaller vehicle while controlling costs and making manufacturing tools more flexible. This profound cultural change allowed different firm operations to work together better, as the hierarchy between them was no longer dominated by the engineers. This change in one higher-level rule led to modifications at the micro level throughout the firm.

5.3.4. Implications for the marketing manager

Managers specializing in marketing must embrace the micro-diversity that reigns in complex systems. This position is almost natural for them, for they know that they must develop positions that distinguish them from others. However, the managers of other functional units within a firm are not aware of this. It rests with the head of marketing to raise awareness among them. Thus, heads of R&D know that they must come up with better products than their competitors, yet without perfectly knowing consumers’ preferences for one function or another. Must quality be improved? Does an option need to be added? A service? Which of two competing design options should be chosen? The marketer who is sensitive to micro-diversity must be ready to guide this decision-making.

It is marketing’s job to ensure that the firm is exposed to the variety around it and to find all sources of commercial uncertainty. The firm thus prepares for change if necessary (here, we see a reproduction of Ashby’s law of variety, 1956).

Marketing takes path dependence into consideration, including developing the story of a brand and creating meaning. However, a decision like the one made by Honda to take on a new market allows a firm to create a tabula rasa of the codes and prior marketing guidelines. The marketing challenge is to come up with a new campaign in a complex system with new rules.

Managers specializing in marketing must also develop the employer margin. Indeed, every firm needs to attract talent in order to develop new products and services and face system evolution. Complex adaptive systems are generally robust, but a firm may see a wide range of results or suffer an accident. In this case, the marketer is responsible for communicating the crisis to avoid the system rules evolving and making the firm’s position – its survival – impossible. In a less critical way, marketers must identify negative (and positive) feedback loops. They can thereby accompany and encourage change or help relax some positions.

As noted by Nilson (1995, p. 24), a marketer’s difficulty in a complex system lies in the timely prediction of system evolution (and thus the detection of weak signals). The marketer’s job, however, involves elaborating a message with no room for doubt, while knowing that he or she may be forced to change this discourse in a considerable way in the future.

5.4. Complex systems and human resource management

Strategic human resource management (SHRM) is based on two fundamental ideas:

- – human resource management has major strategic significance for the firm. Knowledge, skills and employee interactions can form the firm’s strategy and its implementation;

- – human resource practices are instruments to develop a firm’s strategic capacities through proper management of personnel.

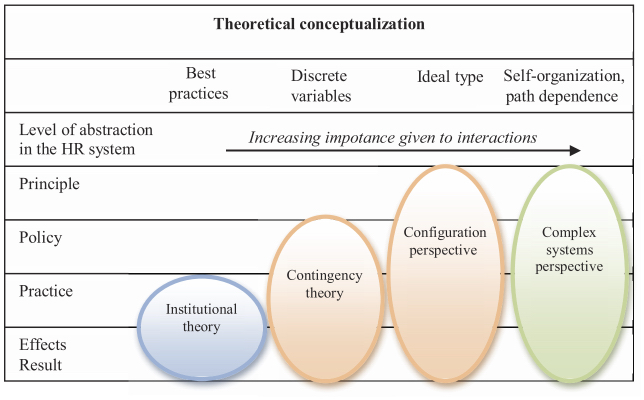

Expressed in these terms, SHRM demonstrates many similarities with the vision of the firm based on RBV – resource-based view – resources (Wernerfelt 1984; Grant 1991). Those trained in RBV think that the competitive advantages of firms stem from the resources at their disposal. As a result, it is the role of the managers to select, develop, combine and redistribute these resources. Not surprisingly, many authors have attempted to develop a connection between human resource management and the theory of the firm based on resources (Wright et al. 2001). However, a number of these authors recognize that beyond the analogy involving the notion of resources, SHRM lacks a theoretical framework comprising every aspect and strategic implication (Delery 1998). Backed by this logic, researchers and particularly Colbert (2004), whose ideas we will focus on later, attempt to incorporate human resource management, the strategic vision based on resources and complex systems.

Next, we will use Colbert’s results (2004) to show the connections between complex systems and the RBV approach within the scope of human resource management. We will then discuss the implications of complex systems on research and human resource management practices.

5.4.1. RBV and complex systems

Several authors note that RBV establishes an interesting framework to justify the importance of human resources in developing firm’s competitiveness. It provides rather little information on the implementation and the way an organization must develop their human resources to attain and maintain a competitive advantage (Delery 1998). This situation is not surprising insofar as the strategic value of RBV resources stem from the complexity of combinations and the inimitable character of the resources. Furthermore, this complexity is difficult to resolve. This difficulty arises from the causal ambiguity connected to resource combinations, the inability to observe certain interactions and path dependence in their accumulation. It is difficult in this case to find a level of direction that maintains the strategic aspect of RBV while making it sufficiently operational.

As Colbert points out (2004, p. 346), the difficulties connected to the use of RBV and potentially echoing in the sphere of complexity are: i) the importance of creativity and adaptability; ii) causal ambiguity; iii) the notions of imbalance and path dependence; and iv) the global representation as a system. This represents a set of characteristics that is particularly important when it comes to describing and analyzing complex systems, as shown in the previous chapters.

Works on SHRM are particularly attentive to the concept of slack, the free time left to individuals. In this – unsupervised – time, employee creativity can be freely expressed. This point was underlined by Penrose (1959, p. 85) in particular: “The availability of unused productive services within it creates the productive opportunity of a given firm. Unused productive services are, for the enterprising firm, at the same time a challenge to innovate, an incentive to expand, and a source of competitive advantage”.

The use of the creative resources employed has given rise to many debates, notably on the duality between control and creativity. For many SHRM authors, the late 1990s and the 2000s were marked primarily by the control of productive resources and little by creative resource management. This is highlighted, for example, by Snell et al. (1996, p. 65): “In the context of achieving sustained competitive advantage, we need less research on the control attributes of SHRM and more research on how participative systems can increase the potential value of and impact of employees on firm performance. If human capital is valuable, we have to learn how to unleash that value”.

Causal ambiguity and path dependence make it difficult to precisely understand the interaction mechanisms through which human resources and the policies that support them create value. To imitate a complex system, we must know how the elements interact. Researchers have shown that hiring human resource (HR) managers to imitate their previous organizational system and methods does not lead to high performative results (Becker and Gerhart 1996).

In the previous chapters, we have specifically insisted on the importance of interactions between the actors within complex systems. These interactions are many of the social links that make some employees valuable. Black and Boal (1994) put forth the notion of “system-level resources” to refer to the strategic organizational abilities that only exist within certain interactions and that are limited to certain relationships. Many works have shown the importance of these strategic connections by using the notions of complementarity or co-specialization (Brumagim 1994).

For Peteraf (1993), the resources particular to the system (and thus to the firm) are quite immobile. This fixedness of certain resources is the source of some firms’ lasting competitive advantage. It is a source of value and profits for the firm (Burger-Helmchen and Frank 2011).

Table 5.2 summarizes and compares the characteristics of the firm’s vision based on resources and complex systems. This table, inspired by Colbert (2004), has been updated with remarks by Stacey and Mowles (2015). The different dimensions highlighted show that the two approaches, RBV and complex systems, have the potential to enrich one another. Since SHRM is supported by firm’s theory based on resources, the potential connections between human resource management and complex systems are possible. They are the subject of discussion in the next section.

Table 5.2. Connects and complementarity between RBV and complex systems (source: Colbert 2004, p. 350)

| Characteristics | RBV | Complexity |

| Creativity/adaptability | The source of competitive advantage lies in latent creative potential, encapsulated in the firm’s resources | CAS create new responses to environmental modifications |

| Complexity and ambiguity | Inimitability stems from social complexity and causal ambiguity | CAS are made up of complex, nonlinear, non-deterministic interactions |

| Imbalance, dynamism, and path dependence | Complex relationships are inherited from firms’ history; imbalance is habitual | The system evolves regularly; imbalance is synonymous with stagnation; history and the timeline are pronounced |

| Resources at the system level | Some resources only exist at the system level through construction | Some characteristics only exist at the system level thanks to agent intervention |

5.4.2. Strategic human resource management

Figure 5.3 illustrates the integration of SHRM into firm’s theory as a complex system. Conceptual approaches and levels of analyses have been represented in this figure. The oval shapes indicate the range of each conceptual approach. As readers turn their attention to the right, the degree of interaction between the system elements becomes greater.

This human resources approach specifically emphasizes that HR systems are very difficult to transfer from one firm to another. Path dependence makes it so rigid that a firm’s HR practices only apply in a very specific framework. By definition, though, the employees in each firm, the organizational culture and the routines in place are specific to each firm. In addition, an optimal SHRM practice for one firm may be ill adapted to another’s needs. This approach also is a large part of self-organization. The implications for HR managers lie at the level of specifying the rules to be put in place. In this approach, their role is to set some basic principles that will be available locally within each unit of the firm. Each unit will self-organize, where the HR managers’ role is to avoid unacceptable drifting and fixing better practices once local actors are self-organized, if necessary.

Figure 5.3. Theoretical conceptualization of the firm and complexity (source: Colbert 2004). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/heraud/creative.zip

The system approach implies that HR managers make it a priority to develop resources at the system level, for these are useful in large quantities, which gives them greater value. Likewise, greater attention must be paid to interfunctional activities. To encourage these, HR managers can encourage personnel to move between different departments and functions in the firm or offer a training period when a new employee arrives. This could involve spending several months in different firm functions to improve knowledge of the system as a whole.

The information system must enable each employee to be quickly and correctly informed of important changes that affect the system as a whole. The formal methods of informing employees must be completed with informal practices (particularly at the unit level), recourse to forums and also a solution to ensure this information exchange, even if numerous works show that these forums are used very little by employees in the end.

One of the missions of HR managers is all the more difficult within the scope of complex systems: establishing performance measures and incitation mechanisms. Usual practices actually focus on local effects and immediate employee performance, yet a complex systems approach must look at long-term impacts and the value created by an employee at different levels. Designing performance measures and remuneration patterns in this case requires considering a large number of factors, often beyond the classical mapping criteria such as a balanced scorecard (Kaplan and Norton 2004). These kinds of works in SHRM are still few and far between, and those that exist could be largely amended. However, the school of thought concerning the micro-foundations of strategy offers new possibilities to echo complex systems within the scope of human resource management and strategic management by focusing on the smaller elements in a complex system (Foss and Pedersen 2014; Felin et al. 2015).

5.5. Conclusion: managers’ creative responses

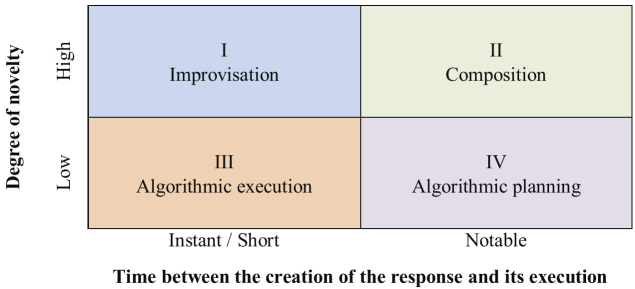

The situations we have described in this chapter have many points in common, such as strategy, marketing or human resources. Although section 5.2 describes what managers must implement to find a solution vis-à-vis the current environment, we have not yet offered a framework for studying creativity in these situations. However, Fisher and Amabile (2011) have contributed considerably towards this analysis. For these authors, managers are never alone and it is not only their creativity, but organizational creativity that is important. This organizational creativity can take different forms, which must be represented and studied on two axes: the higher or lower degree of novelty (regarding solutions, practices and previous routines) and the speed at which the organization must react (which is the time before operational implementation can really take place).

Figure 5.4 represents the four forms of organizational responses that the firm can formulate. The most creative actions are in the top row. Improvisation and composition create new products or results. It is the reaction timelines that distinguishes them. In the case of composition, there is a delay between the moment of creation and its execution. To draw from a musical example, we distinguish here the situation where the composer creates a new melody and the moment when it is played. Inversely, improvisation corresponds to the simultaneity of these actions. To stick to the musical metaphor, this is an improvising jazz group: the group composes and plays at the same time.

Figure 5.4. Creative organizational reactions (source: Fisher and Amabile 2011, p. 17). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/heraud/creative.zip

Improvisation is the intuition that guides the action spontaneously (Crossan et al. 1999). For Vera and Crossan (2005), improvisation has a lower chance of succeeding than composition because the temporal pressure is much greater and not all of the necessary resources may be available (see HR approach, section 5.4). However, the manager and the organization do not always have a choice; they often must organize.

The bottom row of Figure 5.4 refers to algorithms (this term is used by Fisher and Amabile, but the usual term would also be appropriate). Quadrant III refers to an immediate need for a response, but the necessary degree of novelty is low; it is more a matter of adapting an existing solution marginally and hoping for the best. This is the case, for example, during incidents at nuclear plants. The operators have the lists of procedures that they must execute and adapt based on circumstances, but in the end, the degree of freedom to break from these procedures is limited. Inversely, when the possible response time is greater, the algorithm may be optimally designed; the operators create the best possible response.

Managers will understand that they cannot expect the same performance level based on the quadrant the organization is in. Economic laws imply different results when creative actions are executed in different environments (Burger-Helmchen 2013). This is notably what is shown by Wagner et al. (2016) as they explore a set of managerial contexts complementary to those that we have employed in this chapter. Accepting that systems are complex is accepting the idea of possible temporary underperformance, a lower yield and time to adapt structures and allow the actors to self-organize.