PHOENIX

Io son qual fenice

From: ADMETO, RE DI TESSAGLIA

Act 2, scene 1

Io son qual fenice

risorta dal foco

e in me a poco a poco

risorge l’amor.

Il cor già mi dice

ch’il caro mio bene,

godendo, a me viene

e scaccia il dolor.

Like the phoenix,

Reborn from the flames,

In me, slowly, slowly,

Love is reborn.

My heart tells me

That my beloved

Is coming happily to me

And will cast away my pain.

The medieval bestiaries are rather short on information about worms, which is strange, given the filth which abounded in homes, cities, even castles. They depict creatures which could easily be mistaken for striped fish, and the accounts given of their nature and activity do little more than list the places where worms are found or from which they originate: meat, earth, air, flesh, wood, clothes, or leaves. Though their precise place of origin might be vague, it was believed that they sprang to life without the aid of intercourse and that they moved by stretching and constricting their bodies. Many creatures were included in the category of worms: scorpions, leeches, millipedes, ticks, and all manner of unpleasant crawly things.

How puzzling this is: surely the worm in its various manifestations was a creature which the readers and writers of bestiaries – indeed, anyone with eyes – would have seen often and everywhere, and yet little effort is made to tell stories about their origin or to make moral links between their behavior and that of humans.

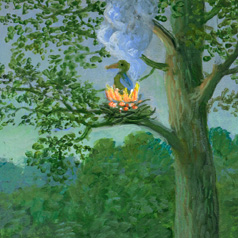

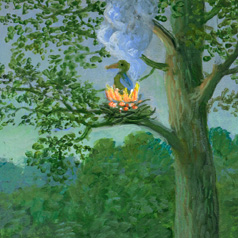

There was, however, one creature that sprang, at least in some versions, from a worm. It is the Arabian Phoenix, that most wondrous of birds: magnificent in purple and gold and capable of eternal - however interrupted - life. This bird, as written about by Herodotus, Ovid, Lucan, and Pliny, lives five hundred or more years, and when he senses that he is soon to die, he repairs himself to a tree, wherein he builds a nest. In this nest, he dies, and some time after his death, a worm is discovered, from which a new phoenix will rise.

During the centuries that elapsed between the accounts of the pagan writers and that of the Seventh Century writer, Isidore of Seville, the Phoenix became both a suicide and a pyromaniac, for the legend took on what has become its best-known element: the Phoenix, nearing the end of its life, builds a nest of rich spices and immolates itself by turning to face the sun and flapping its wings to create a fire, only to spring back to life from its own ashes after three days.

This image of purified rebirth was irresistible for Christian writers. St. Ambrose, writing his brother’s funeral oration in 375, gave the Phoenix myth as evidence for human resurrection: “There is a bird in Arabia called the phoenix. After it dies, it comes back to life, restored by the renovating fluid in its own flesh. Shall we believe that men alone are not restored to life again?” His contemporary, Lactantius, is equally certain about the spiritual nature of resurrection, though he is uncertain about the bird’s sex: “whether male or female or neither….” The symbolism is perfect: just as Christ is sacrificed and is reborn, so too the consenting Christian, though his body perishes, will be purified and reborn in Christ.

What might be called the Elephant Problem is evident in the way the artists of Medieval bestiaries presented the Phoenix. Now, it is safe to presume that, though most had not, some Europeans at least had seen elephants, either in Africa or India, and had brought back sketches or descriptions. But they had seen them. The fact that no one – at least to the best of my knowledge – had actually seen a phoenix in no way prevented the artists from painting them.

One bird presented in a 12th century British manuscript is indeed identifiably a bird, though the bird it most resembles is, unfortunately, a dodo. The Fitzwilliam Museum has a manuscript with another bird, this one with party-colored stripes and looking more wall-papered than feathered. Manuscript phoenixes are occasionally rash in their choice of location for immolation. Those who select flat surfaces, with fires burning beneath, run the risk of looking suspiciously like, well, like a summer barbecue. Those who choose to insert themselves for burning within concave nests fare far better, at least in the visual sense.

However unlikely it might be that Handel had much first-hand experience of the phoenix, the aria he wrote for the soprano in Admeto accurately conveys the joy that comes when hope causes love to rise from its own ashes. The aria was written for one of his most famous singers, Faustina Bordoni Hasse, and was sung in a benefit concert of the opera. Curiously enough, this is one of the few arias known to have been sung by both of those arch-rivals, Faustina and Cuzzoni, though Faustina sang it when she played Alceste and Cuzzoni when she sang Antigona.

The triadic coloratura gives a sense of someone doing handsprings for joy, for her heart tells her that her beloved is on his way back to her, and she is sure that his return will drive away all suffering. These handsprings, however, are a bit premature, for she has yet to discover that, during the time she has been agreeing to die in his place, the man she loves has been taking up with another woman.