Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606 – 1669) was born near the town of Leiden in Holland, where his father owned a mill on the banks of the Old Rhine. The family derived its name from the mill, which was called De Rijn (Dutch for “the Rhine”). Years later, after his art career was established, Rembrandt signed his work with only his distinctive first name.

From his youth Rembrandt trained to be an artist. Around 1632 he moved from Leiden to Amsterdam, where citizens of all incomes — from humble craftsmen to wealthy businessmen—bought art objects. In the seventeenth century, Holland was a powerful nation made rich by trading. Amsterdam was the busiest port city in Europe, and its markets sold fabrics, spices, flowers, fish, and cheese. This period in the nation’s history, when art, philosophy, literature, and the sciences flourished, is often called the Dutch Golden Age.

Rembrandt quickly became one of the leading artists in the city. He painted a wide variety of subjects: portraits of middle-class merchants and wealthy professionals, scenes of historic events, and stories from the Bible and Roman mythology. His busy workshop was both a studio and a school where pupils lived, studied, and worked alongside him.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait Leaning on a Stone Sill (detail), 1639, etching, White / Boon 1969, no. 21, State ii / ii, National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection

Rembrandt didn’t always work inside his studio. Often he went for walks in the countryside to observe nature. He took along his sketchbook and made drawings of the rural environment — the farms, marshes, trees, boats, bridges, mills, cottages, and vast sky — that made up Holland’s unique landscape.

The Amstel is an important river that had been channeled into a canal running right through Amsterdam. Rembrandt followed the river south, out of the city, and sketched View over the Amstel looking back toward Amsterdam. Small boats navigate the many canals that crisscross the countryside, transporting goods and people.

Rembrandt van Rijn, View over the Amstel from the Rampart, c. 1646 / 1650, pen and brown ink with brown wash, Rembrandt Chronology, no. 13, National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection

It’s hard to imagine the Dutch landscape without windmills. With much of the country below sea level, windmill power was used to drain the land of water so that it could be farmed. Windmills were also used to grind wheat, corn, and barley. They contributed to the country’s productivity, and the Dutch were proud of this source of prosperity.

In the etching The Windmill, Rembrandt describes in great detail an eight-sided grain mill and nearby cottage. As a sign of national pride, people collected pictures of the local scenery, and prints such as this one were in demand.

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Mill, 1645 /1648, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Widener Collection

Although Rembrandt made many drawings and prints of landscapes throughout his life, he created few paintings of them. The Mill is his largest one. It does not depict a specific place, but instead it is an imaginary scene that Rembrandt devised from his drawings. The windmill sits high on a hill, its sails full, silhouetted against a cloudy sky. Interested in the effects of changing weather, Rembrandt shows the sunlight breaking through the clouds after a storm. People around the windmill are engaged in everyday activities: a woman washes clothes at the edge of the river, a fisherman rows home, and a woman walks with her child.

The land and people are engulfed in deep shadows, while the windmill, sunlit on high ground, stands out against the sky. Rembrandt is known for his strong contrasts of light and dark. He used light to feature some areas of a picture, and he left other parts in shade. This technique, called chiaroscuro (from the Italian words for “light” and “dark”), can make an ordinary scene look dramatic. Rembrandt composed many of his portraits in a similar way. In his Self-Portrait of 1659, the light is cast on his face to draw attention to it, leaving much of his body in shadow.

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Windmill, 1641, etching, White/Boon 1969, no. 233, National Gallery of Art, Gift of W. G. Russell Allen

Rembrandt did not paint many landscapes, but one “landscape” with which he was very familiar was the terrain of his own face. He closely studied his face and made sketches, etchings, and paintings of himself more than a hundred times. In a way, he was his favorite model. He could experiment with various techniques and practice drawing facial expressions that conveyed different feelings, such as fear, worry, melancholy, surprise, or amusement. Painted over the years, his self-portraits show him young and old, dressed in everyday clothes or wearing theatrical costumes and elegant hats. And in some, Rembrandt examines his identity as an artist.

Rembrandt was fifty-three years old when he painted the self-portrait wearing an artist’s cap and a brown painter’s jacket. The light illuminates his head, drawing attention to his deep-set eyes, wrinkled cheeks, and furrowed brow. To create his scruffy gray hair, Rembrandt used the end of his paintbrush handle to scratch through the wet paint to make curls. Light also accents his left shoulder and clasped hands, but most of the painting is in dark shadow. What might he be thinking and feeling?

Make a self-portrait

You will need:

A mirror

Paper

Crayons, markers, colored pencils, or paints

Making a self-portrait is a way of getting to know yourself. First, think about these questions: What makes you who you are? What are your interests? Your dreams? Select clothing that reflects something about you. You might want to include objects in your self-portrait that help describe your personality. Think of a self-portrait as a personal introduction. What do you want to tell people about yourself? How do you want people to remember you?

Next, study yourself in the mirror. What features make you unique? Try out different facial expressions — smile, frown, or laugh — and strike different poses. Do you want to look relaxed, physically active, or deep in thought? Then, try to capture your appearance and character on paper. Like Rembrandt, experiment by creating many different self-portraits. You might even wish to put yourself in a landscape or place that is special to you.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait, 1659, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Andrew W. Mellon Collection

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait, c. 1637, red chalk, Rembrandt Chronology, no. 7, National Gallery of Art, Rosen-wald Collection

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait in a Cap, Open-Mouthed, 1630, etching, White/ Boon 1969, no. 320, National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection

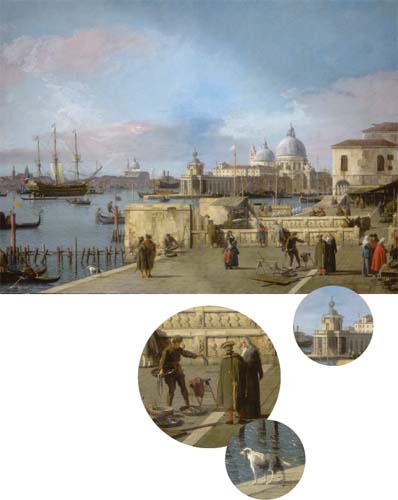

Giovanni Antonio Canal (1697 – 1768) is best known for his painted views of his hometown: Venice, Italy. Capturing its appearance and distinctive character, his paintings transport viewers back to this famous city on the water. He was nicknamed Canaletto (the little Canal) to distinguish him from his father, who was also an artist. Canaletto specialized in topographical views—paintings that describe the landscape and architecture of a particular place. His paintings were popular because he recorded in vivid detail the appearance of the city and the diverse activities of its people. To achieve convincing realism in his scenes, Canaletto first made several sketches outside. He then took these quick drawings back to his studio, where he painted his large-scale canvases. He worked on the architecture before he added the figures on the plazas and canals. Canaletto’s city views are much more than a painted “photograph”: he often improved the appearance of a place, making it look better than it actually was!

Giovanni Antonio Canal, detail of engraving by Antonio Visentini, after G.B. Piazzetta, in Prospectus Magni Canalis Venetiarum, 1735, Biblioteca nazionale Marciana, Venice

In the eighteenth century, Venice became a favorite tourist destination in Europe. With its beautiful setting, many canals, and magnificent architecture, the city attracted foreign visitors who enjoyed its carnivals, regattas, festivals, and theater. Travelers wanted souvenirs of their visit to Venice. Before cameras were invented, tourists bought paintings and drawings to take home. Canaletto painted scenes of Venice often, and he built a successful career by selling his work to wealthy tourists.

Canaletto, Entrance to the Grand Canal from the Molo, Venice, 1742/1744, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mrs. Barbara Hutton

A large Italian port on the Adriatic Sea, Venice was an important center for trade between Asia and Europe. It also boasted a thriving fishing industry. This view shows the popular waterfront leading to the Grand Canal, the main waterway through Venice. Large oceangoing ships, including one with a British flag, have dropped their sails and are anchored to unload their cargo and tourists. Gondolas glide across the glistening water, ferrying passengers across the canals. In the center is the Customs House, where goods are unloaded and taxed. A small globe above its dome symbolizes the city’s overseas trade. Groups of people gather along the dock, stop to chat with one another, and shop. Fishermen display the day’s catch of eels and mussels in round wooden trays.

Located at the very heart of Venice are Saint Mark’s Square and the Church of Saint Mark with its elaborate architecture, bluish domes, and shimmering mosaics. To the right is the pink marble Doge’s Palace, once home to the elected rulers of Venice.

Around three bronze flagpoles, merchants set up tables, take goods out of trunks, and display bolts of cloth at booths protected by umbrellas. These activities, and the ships off in the distance, highlight Venice’s role as a center of trade. Canaletto included about two hundred figures in this painting!

Canaletto, The Square of Saint Mark’s, Venice, 1742 / 1744, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mrs. Barbara Hutton

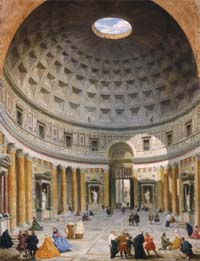

While Canaletto was painting views of Venice, Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691 – 1765) was working as a “view painter” in Rome. Panini specialized in landscape and architectural views of the most famous and memorable sights of Rome, including the Pantheon and Saint Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican. Similar to works by Canaletto, Panini’s paintings were popular with visiting tourists, who bought them as a souvenir of their travels.

Postcard Memories

Take an imaginary trip to Italy and write a postcard to a friend.

Choose a painting by Canaletto or Panini and imagine you can “jump” into the scene. What would you do? Where would you explore? Who would you meet?

Write a postcard from this place and describe your travels. Begin with, “I visited ______and I saw _______ .”

Create a postcard picture of your hometown

Make a postcard by cutting a piece of white cardstock or watercolor paper into a rectangle (3.5 × 5 inches or 4 × 6 inches). On one side, use colored pencils to draw a view of your hometown. Choose a well-known park, school, monument, or shopping center. Add details of the landscape, buildings, and people. Divide the other side in half. On the left side, write a note to a friend, a family member, or yourself! Share a special memory of your hometown. On the right side, write the address on the postcard, place a stamp in the upper right corner, and send it in the mail.

Giovanni Paolo Panini, Interior of Saint Peter’s, Rome, c. 1754, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund

This view of Saint Peter’s shows off the church’s large interior and elaborate architectural decorations. The worshipers and visitors provide a sense of scale and enliven the space.

Giovanni Paolo Panini, Interior of the Pantheon, Rome, c. 1734, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection

With the largest concrete dome in the world, the Pantheon has been one of the most popular monuments of classical Rome. Built as a Roman temple, it was later converted to a Christian church.

In the mid-nineteenth century, landscape painting grew in popularity among artists in the United States. Captivated by the sweeping vistas of their country, many of them explored and painted the picturesque valley of New York’s Hudson River. One of these “Hudson River School” painters was Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823 – 1900).

Born on Staten Island, New York, Cropsey trained to be an architect, but his real love was painting. In the 1840s he made summer sketching trips to New Jersey, Upstate New York, Vermont, and New Hampshire. He and his wife moved to London in 1856, where they lived for seven years before returning to America.

Cropsey became best known for his paintings of autumn landscapes. His works were more than just descriptions of nature: they were patriotic celebrations of the wonders and promises of a young nation carved from the wilderness.

Jasper Francis Cropsey (detail), Collection of Time & Life Pictures (photo: Tony Linck)

Painted in 1860, this monumental view of the Hudson River Valley shows a scene set about sixty miles north of New York City, between the towns of Newburgh and West Point. From a high vantage point on the west side of the Hudson River, a small stream leads to the wide expanse of the river. The distinctive profile of Storm King Mountain is off in the distance. Behind thick gray-blue clouds, the sun’s piercing rays give a mellow glow to the hazy atmosphere. Celebrating the richness and variety of autumn foliage, tall, graceful trees in the foreground frame the view into the distance. Red oak, sugar maple, birch, and chestnut trees—having assumed their different shades of yellow, bronze, scarlet, and orange—are intermingled with the evergreen hemlocks and pines.

Jasper Francis Cropsey, Autumn — On the Hudson River, 1860, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of the Avalon Foundation

Remarkably, Cropsey painted Autumn—On the Hudson River while he lived in London. He relied on his memory and on sketches he made of autumn in rural New York. Cropsey’s largest painting, measuring almost nine feet wide and five feet tall, took more than a year to complete, but it was an immediate success when it was exhibited in London. The painting created a sensation among English viewers who had never seen such a colorful panorama of fall foliage. (Autumn in Britain is far less colorful than in the eastern United States because there are fewer deciduous trees.) Cropsey also displayed specimens of North American leaves alongside his painting to persuade skeptical visitors that his rendition was botanically accurate.

Autumn — On the Hudson River is a sweeping vista with precise details. The magnificent panorama, with closely observed elements, conveys an idea of the magnitude and splendor of the American landscape.

Look closely to find:

A group of hunters with their dogs

A log cabin

A winding stream

Large boulders around a pool of water Grazing sheep

Children playing on a bridge

Cows wading in the water

Boats crossing the river

A small town nestled along the shore

Imagine you have traveled to this place

What sounds might you hear?

What might you smell?

How would you dress for this trip?

What parts of the landscape would you explore?

Where would you stand for the best view of the mountain?

What might you see from the top of a mountain?

How would this place look in the winter? In the summer?

Each season presents a new inspiration for artists. During the season of autumn, wander through your backyard, neighborhood, or a park.

Look at leaves the way an artist might.

Examine the range of colors, from bright reds, oranges, and yellows to browns and greens.

Notice the different sizes and shapes of leaves—big, small, thin, fat, round, and pointy.

Look at the textures and vein patterns of leaves.

Collect a variety of leaves that have fallen to the ground and create a work of art with them.

Leaf Rubbing

You will need:

Leaves

Plain white paper

Crayons

On a piece of plain white paper, arrange the leaves (with the vein side up) in a pattern you like.

Lay another sheet of plain white paper on top of the leaves.

Select a crayon and peel off its paper wrapper.

Using the side of the crayon, gently rub it over the top sheet of paper.

An image of the leaf will begin to appear on the paper! Experiment with different colors and leaf arrangements.

Leaf Collage

You will need:

Leaves

Newspaper

Rubber cement

Paper

Clear contact paper

Clean the leaves you’ve collected by rinsing them in warm water. Carefully blot them dry with a paper towel.

Place the leaves between sheets of newspaper, and then put them between two heavy books. In about a week, the dried leaves should be flat and stiff.

Arrange the dried leaves in an interesting design on a piece of paper. Use rubber cement to glue them in place.

Let the rubber cement dry for one day. To protect the surface, cover your collage with clear contact paper.

“Have you ever reclined upon some gentle slope, some hillside in a beautiful country with your eyes half closed and your mind away from care, dreaming of … the lovely and beautiful in nature and art with a far away and o’er the hills feeling of the chameleon sky, the glowing sunshine and soothing shadows — the distant smoky town — the rich autumnal foliage, bits of green pasturage and nibbling sheep and stately trees, a stream of water winding in and out around some wooded headland…” Jasper Francis Cropsey

Born in England, Thomas Moran (1837 – 1926) grew up near Philadelphia after his parents moved to the United States in 1844. A promising young artist, he served as an apprentice in Philadelphia and then traveled to Europe, where he was influenced by the work of the British landscape painter J.M.W. Turner. An avid traveler, Moran spent his long career painting diverse landscapes, from Pennsylvania and Long Island to Arizona, Idaho, Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Montana, California, and even Cuba, Mexico, and Italy. He became famous for his paintings of Western territories. They were received with great enthusiasm by a public who saw westward expansion as a symbol of hope for America.

Moran’s adventures in the West began in 1871. Just a few months earlier a magazine publisher asked him to illustrate an article about Yellowstone, a wondrous region of the Wyoming Territory that was rumored to have steam-spewing geysers, boiling hot springs, and bubbling mud pots. Eager to be the first artist to record these astonishing natural wonders, Moran quickly made plans to travel west.

He joined geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden on the first government-sponsored survey expedition of Yellowstone Valley. This area, while virtually unknown, was a source of great interest and curiosity. Hayden’s goal was to map and measure Yellowstone, and Moran’s role was to record the scenery of the region. The artist made many watercolor sketches, which became the first color pictures of Yellowstone seen in the eastern United States.

Photographic portrait (detail) of the American artist Thomas Moran by Napoleon Sarony, c. 1890 – 1896. Photogravure (photomechanical) print. Image courtesy of the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC

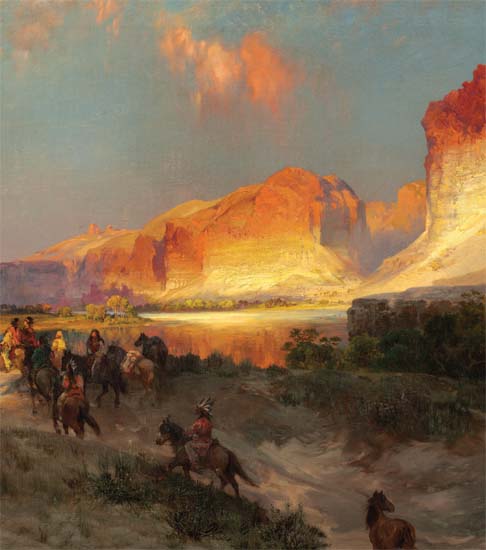

Yellowstone was Moran’s ultimate destination in the summer of 1871, but before he joined Hayden’s expedition, the artist stepped off the train in Green River, Wyoming, and discovered a landscape unlike any he had ever seen. Rising above the dusty railroad town were towering cliffs of sandstone carved by centuries of wind and water. Captivated by the bands of color, Moran made his first sketches of the American West.

Over the years, Moran repeatedly painted the magnificent cliffs of Green River, the western landscape he saw first. Green River Cliffs, Wyoming was painted in 1881, ten years after his first trip west. Moran referred to his sketches in his studio, but he also took some artistic license since he believed it was better to express the distinct character of the region than it was to record a view with strict accuracy. Green River was a busy railroad town when Moran arrived in 1871, yet no indication of the town — the Union Pacific Railroad, hotel, church, schoolhouse, and brewery—is seen. Instead, the dazzling colors of the sculpted mountains and a caravan of American Indians are the focus. Moran erased the reality of commercial development and replaced it with an imagined scene of the pre-industrial West that neither he nor anyone else could have seen in 1871.

Thomas Moran, Mountain of the Holy Cross, 1890, watercolor and gouache over graphite on paper, National Gallery of Art, Avalon Fund, Florian Carr Fund, Barbara and Jack Kay Fund, Gift of Max and Heidi Berry and Veverka Family Foundation Fund

Soon after Moran returned to the East, Hayden and others began promoting the idea that Yellowstone should be protected and preserved. Since no member of Congress had seen Yellowstone, Moran’s watercolors played a key role in the congressional decision to pass the bill creating the first national park, which established Yellowstone National Park and the national park system. Mount Moran in the Grand Teton Mountains was named for the artist in honor of his role in preserving America’s wilderness.

Yellowstone was just the beginning for Moran. He made numerous trips to the West, painting scenes of the Grand Canyon, Yosemite Valley, the Grand Tetons, Colorado’s Mountain of the Holy Cross, and the Snake River. Moran’s works sparked the American imagination and helped the national parks become popular tourist destinations.

Thomas Moran, Green River Cliffs, Wyoming, 1881, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of the Milligan and Thomson Families

“I have always held that the Grandest, Most Beautiful, and Wonderful in Nature, would, in capable hands, make the grandest, most beautiful, or wonderful pictures, and that the business of a great painter should be the representation of great scenes in nature.” Thomas Moran to Ferdinand Hayden, March 11, 1872

Like Moran, George Catlin (1796 – 1872) became famous for his paintings of the American West. Born in Pennsylvania, Catlin first trained to be a lawyer, and he enjoyed sketching the judges, jurors, and defendants he encountered on the job. Soon he decided to become a portrait painter. After seeing a delegation of Plains Indians in Philadelphia, he dedicated himself to recording the lives and customs of American Indians. He wanted to document their way of life — people at work and play, families, leaders, and the landscape where they lived — before it vanished. Catlin spent many years traveling with different tribes, and he kept a detailed diary of his journeys. He created more than five hundred paintings. After his extensive travels, he put his paintings on view alongside American Indian artifacts in an exhibition he called The Indian Gallery. To educate viewers about this disappearing culture, he took the collection on tour to several cities on the East Coast and then to London.

White Cloud: Head Chief of the lowas

Mew-hu-she-kaw, known as White Cloud or No Heart-of-Fear, was one of several tribal chiefs of the Iowa people in the mid-nineteenth century. This portrait shows not only the traditional dress of the Iowas but also the chief’s important status within the tribe and his brave nature. He wears a white wolf skin over the shoulders of his deerskin shirt, strands of beads and carved conch shell tubes in his pierced ears, and a headdress made of a deer’s tail (dyed vermillion) and eagle’s quills above a turban of (possibly otter) fur. His face is painted red and marked with green handprints, a sign that he was very good at hand-to-hand fighting. The necklace of bear claws testifies to his skill, because it was reserved for those who earned success as hunters and warriors. Catlin admired the American Indian people, and his portraits emphasize their dignity and pride.

George Catlin, The White Cloud, Head Chief of the lowas, 1844 / 1845, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Paul Mellon Collection

George Catlin, A Buffalo Wallow, 1861 / 1869, oil on card mounted on paper-board, National Gallery of Art, Paul Mellon Collection

For many tribes on the Great Plains, buffalo were an important source of food, clothes, cooking pots, and tools.

Artists often leave their studios and travel to new places for inspiration. In the summer of 1905, Henri Matisse (1869 – 1954) left Paris for the French village of Collioure. Then a quiet fishing town, Collioure nestles between the Mediterranean Sea and the Pyrenees Mountains close to the Spanish border. The landscape and lifestyle there were very different from Paris. The brilliant light in the south of France, reflected off the sea, captivated Matisse.

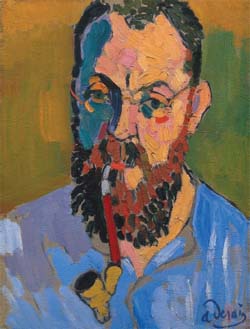

André Derain, Portrait of Henri Matisse, 1905, oil on canvas, Tate Gallery, London, Great Britain © ARS, NY. Photo credit: Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

“We were always intoxicated with color, with words that speak of color, and with the sun that makes colors live.” André Derain

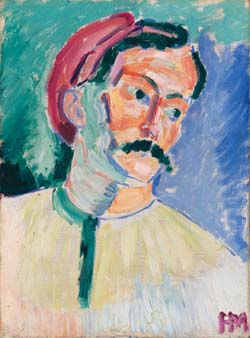

After settling with his family in a hotel, Matisse invited his friend, the young painter André Derain (1880 – 1954), to join him in Collioure. Matisse and Derain worked every day, often painting side by side around the village. They sketched the boats in the harbor, the fish market, and the nearby Pyrenees. They even made pictures of each other. Using paints straight from the tube with little mixing of pigments, they applied vibrant—often unexpected—colors directly to their canvases. Their collaboration led to a new freedom in creating art: the use of color to express the feeling of a place.

Henri Matisse, André Derain, 1905, oil on canvas, Tate Gallery, London, Great Britain © Succession H. Matisse, Paris / ARS, NY. Photo credit: Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

In the fall of 1905, Matisse and Derain showed their paintings at an important exhibition in Paris called the Salon d’automne. People were shocked by the bold brushstrokes and strange color combinations. Many laughed at the paintings. One art critic nicknamed the artists fauves (the French word for “wild beasts”) because of their expressive brushstrokes and loud colors. Matisse and Derain inspired many artists to explore color in new ways.

Matisse and Derain do not show Collioure as it looked in real life. Instead, the artists conveyed the intensity and energy of Collioure’s blazing sunshine by painting with dazzling colors.

Look at Open Window, Collioure, Matisse’s view of the town port. Visible through the window, small boats bob on pink waves under a sky banded with turquoise, pink, and periwinkle. Vibrant outdoor light pours through the window and onto the flower pots on the sill, coloring the windows mauve, azure, and pink.

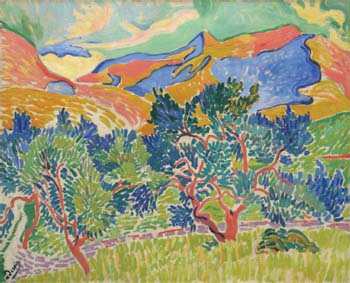

Turning from the sea in Mountains at Collioure, Derain painted the olive groves with the steep hills of the Pyrenees in the background. Notice how Derain used a variety of brushstrokes to paint this rugged landscape. Examine how the twisting red lines form the trunks of the olive trees. Derain’s bold, separated stripes of blues, grays, and greens create a rhythmic pattern of leaves ready to wave in a breeze. Broad, sweeping strokes of color form the mountains rising behind the trees and reaching to the sky.

“When I realized that every morning I would see this light again, I couldn’t believe how lucky I was.” Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, 1905, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney

André Derain, Mountains at Collioure, 1905, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, John Hay Whitney Collection

Matisse enjoyed staying in warmer places during the winter months, and he liked to watch sunlight shimmering on the sea. After his summer with Derain, he returned to Collioure and vacationed at other seaports on the French coast of the Mediterranean Sea. He also visited Italy, North Africa, and Tahiti. Beasts of the Sea is a memory of his visit to the South Seas.

Many years after creating his fauve paintings, Matisse developed a new form of art: the paper cut-out. Still fascinated by the power of color, the artist devoted himself to cutting painted papers and arranging them in designs. “Instead of drawing an outline and filling in the color … I am drawing directly in color,” he said. Matisse was drawing with scissors!

Henri Matisse, Beasts of the Sea, 1950, paper collage on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund

What shapes do you recognize in Beasts of the Sea? Find shapes that remind you of

Henri Matisse at work on a paper cut-out in his studio at the Hôtel Régina, early 1952, Nice-Cimiez. Hélène Adant (20th c.) © Copyright Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, U.S.A.

After cutting shapes that reminded him of a tropical sea, Matisse arranged the pieces vertically over rectangles of yellows, greens, and purples to suggest the watery depths of an undersea world.

Create a colorful collage

Use colored papers, or like Matisse, make your own colored paper by painting entire sheets of white paper in one color. Paint on heavy cardstock so the paper doesn’t curl as it dries. Next, find a theme for your work. Like Matisse, choose a view from your window or a memory from vacation. Use scissors to cut the paper into different shapes that remind you of that place. Arrange your cut-out shapes on a large piece of colored paper. Move the pieces around and experiment with layering until you are satisfied with the design, then glue your shapes in place.

While creating the cut-outs, Matisse hung them on the walls and ceiling of his apartment in Nice, France. “Thanks to my new art, I have a lush garden all around me. And I am never alone,” he said.

Throughout his childhood in Columbus, Ohio, George Bellows (1882 – 1925) divided much of his time between art and sports. While attending Ohio State University, he created illustrations for the school yearbooks, sang in the glee club, and played basketball and baseball. Bellows left college before graduating, and even turned down an offer to play professional baseball with the Cincinnati Reds, all because he wanted to become an artist.

In 1904 Bellows left the Midwest for Manhattan, where he enrolled in the New York School of Art. There he studied under the well-known teacher and artist Robert Henri, who encouraged students to be inspired by real life: “Draw your material from the life around you, from all of it. There is beauty in everything if it looks beautiful to your eyes.” Bellows became linked with a group of artists who were also inspired by Henri. Critics dubbed them the Ashcan School due to the way they showed the grittier side of life in the city.

Bellows’ early paintings focused on dynamic city scenes: busy streets, boxing matches, construction sites, commercial docks, and poor neighborhoods. He eventually expanded his subjects to include seascapes, country scenes, and portraits of friends and family. His work met with popular success during his lifetime. Bellows died at age forty-two from a ruptured appendix.

George Bellows, c. 1900, Peter A. Juley & Son Collection. Smithsonian American Art Museum

Bellows captured the whirlwind of activity on a winter day in his painting New York. The picture is a congestion of buildings, signage, and people and goods on the move. Motorcars mingle with horse-drawn conveyances and trolleys while pedestrians hurry along sidewalks. When Bellows created this work in 1911, the traffic light had not yet been invented. In the painting you can see a policeman trying to direct traffic, a street cleaner busy sweeping, and a woman stopping at a vegetable cart. Bellows’ use of expressive brushstrokes adds to the energy of the scene.

George Bellows, New York, 1911, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

“Some day far in the future it will be pointed out, no doubt, as the best description of the casual New York scene left by the reporters of the present day.” New York Times, 1911

Although the painting’s general location is Madison Square at the intersection of Broadway and Twenty-third Street, Bellows imaginatively combined elements that could not be seen from a single viewpoint. Many of Manhattan’s most famous features are seen: skyscrapers, apartment buildings, elevated train tracks, a subway entrance, electric signs, advertising billboards, and a tree-lined park. Although these features are familiar today, they represented an exciting, modern experience for most people at the beginning of the twentieth century.

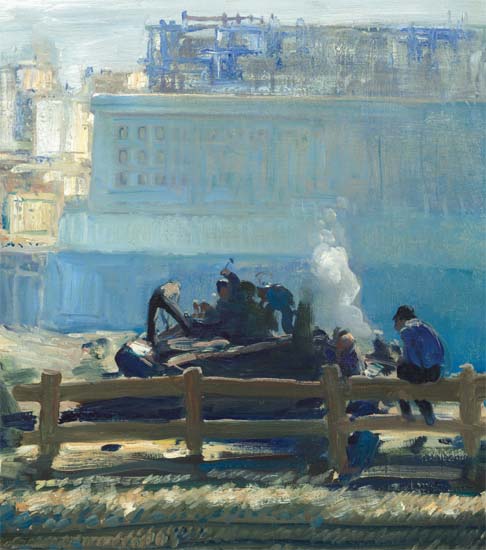

In the early twentieth century, New York was changing into a metropolis with vast building projects that included new bridges and skyscrapers. Construction of the Pennsylvania Railroad Station took place from 1906 to 1910. This complex endeavor required tearing down entire blocks of old buildings, digging giant pits, and boring several sets of large tunnels under the Hudson and East rivers. The energy, drama, and scope of the engineering project fascinated Bellows, and he began a series of paintings to study construction scenes by day and night, in summer and winter.

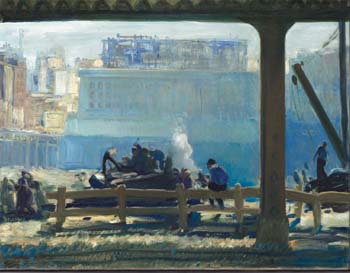

Blue Morning shows the nearly completed station enveloped in morning haze. Construction workers are busy in the excavated pit; a crane arm rises. The elevated train tracks and a vertical girder frame the scene. Bellows used tones of blue, lavender, and yellow to create a sense of the morning light.

George Bellows, Blue Morning, 1909, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection

“Be deliberate. Be spontaneous. Be thoughtful, and painstaking. Be abandoned, and impulsive. Learn your own possibilities.” George Bellows

“I paint New York because I live in it and because the most essential thing for me to paint is the life about me, the things I feel to-day and that are part of the life of to-day.” George Bellows

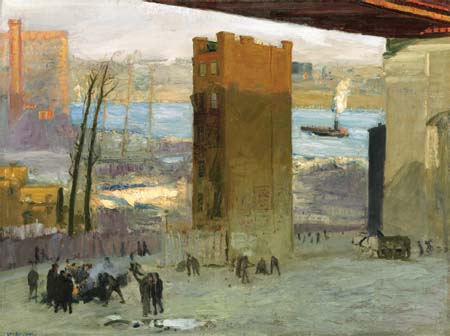

The Lone Tenement is set under the Queens-boro Bridge, which was completed in 1909 to connect the boroughs of Manhattan and Queens. Dwarfed by the newly constructed bridge, the last remaining row house stands alone, the sole survivor of its former busy neighborhood. People gather around a fire to keep warm in the shadow of the bridge. Sunlight sparkles on the East River as a ship passes by. Instead of celebrating the bridge as an engineering accomplishment, Bellows focuses on the lives of ordinary people who were affected by its construction.

Documenting Changing Times

Many artists in the early twentieth century, including Bellows, worked as sketch reporters. In an era before the widespread use of photography, they drew illustrations for newspapers and magazines as a way to document events in the city. Along with many of the Ashcan School artists, Bellows was concerned about the social issues of his time, including poverty and the way large building projects changed neighborhoods.

Write a headline

Write a news story headline (for a newspaper, magazine, or website) for each of the paintings by Bellows in this section. Summarize the main idea of each picture in an interesting way to catch people’s attention.

Be a sketch reporter

Choose a headline or news story from a newspaper, magazine, or television report. Make a drawing or painting that illustrates the story. Capture the key points of the story in one picture.

George Bellows, The Lone Tenement, 1909, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection