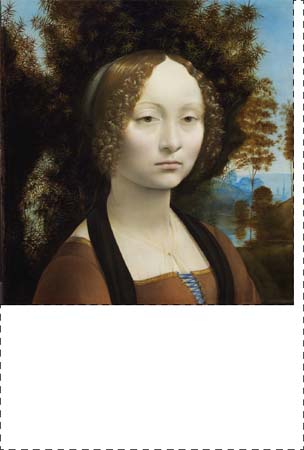

Ginevra d’Amerigo de’ Benci (1457 - c. 1520) lived in Florence, Italy, five hundred years ago. The daughter of a wealthy banker, she was the second of seven children. Her nickname, La Bencina (“little Benci”), was likely an endearing reference to her delicate appearance and gentle spirit. Ginevra was a poet (although only a single line of her work survives), and she was praised by those who knew her for her intellect and virtuous character. Leonardo painted her portrait around the time she married in 1474.

Ginevra was about sixteen years old in this portrait. It presents her as a refined young woman with a porcelain complexion. Her modest brown dress is enlivened with elegant details: blue ribbon lacing, gold edging, and a sheer white blouse fastened with a delicate gold pin or button. A black scarf is gently draped over her slender shoulders and neck. Her golden hair is styled simply—parted in the middle and pulled back in a bun—leaving ringlets to frame her face. Without the distractions of luxurious fabrics and sparkling gems, Ginevra herself attracts attention. Her brown eyes gaze steadily from under almond-shaped lids, and her lips are closed in a quiet line. Unlike portraits in profile that were more typical at the time, Ginevra’s portrait shows her in a three-quarter view as a way to reveal more about her.

Describe Ginevra’s expression. How does she feel? What might she be thinking about? What aspects of her personality does the portrait convey?

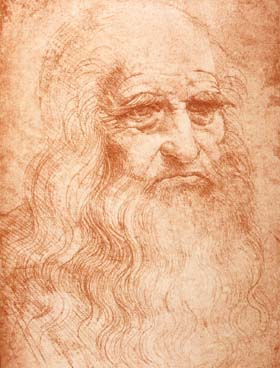

Leonardo da Vinci, Self-Portrait (detail), c. 1512, Biblioteca Reale, Turin, Italy. Photo credit: Ali-nari / Art Resource, NY

“A face is not well done unless it expresses a state of mind.” Leonardo da Vinci

Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) lived during an exciting period known as the Renaissance (French for “rebirth”), a time recognized for a renewed interest in knowledge, the arts, and science. He was an artist as well as an inventor, architect, engineer, musician, mathematician, astronomer, and scientist. In many ways, his intellectual curiosity, careful observation of nature, and artistic creativity characterized the Renaissance itself.

Born in the small town of Vinci, outside Florence, Leonardo moved to the city at the age of twelve to train in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, a leading artist of the time. Leonardo was just twenty-two years old when he painted this portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci. It is the first of only three known portraits Leonardo painted in his career. The portrait may have been commissioned by Ginevra’s older brother Giovanni on the occasion of her engagement.

Throughout his life, Leonardo embraced opportunities to experiment with materials and explore artistic approaches. Ginevra’s portrait was among his earliest encounters with the medium of oil paint. Leonardo used his fingers and the palm of his hand to mix the wet paint, which enabled him to blend colors and create soft, delicate edges that allowed for subtle transitions from light to shadow. Evidence of Leonardo’s innovative technique remains on the painting: his fingerprint is visible on the surface, where the sky meets the juniper bush above Ginevra’s left shoulder.

This was among the first portraits created in Florence that showed a sitter outdoors. In fact, Leonardo gave almost as much attention to the landscape as he did to Ginevra. Behind her is a tranquil scene with small trees lining the banks of a pool of water and a town nestled in the hills under a misty sky.

The large plant behind Ginevra’s head is a juniper bush, an evergreen with sharp, spiky leaves. It is a witty pun on Ginevra’s name: ginepro is the Italian word for juniper.

Both the figure and the landscape have been praised for their lifelike appearance. The painting demonstrates Leonardo’s careful observation of the natural world, a practice he continued throughout his career that came to transform Renaissance painting.

Leonardo da Vinci, Study of female hands (detail), drawing, Royal Library, Windsor Castle, Windsor, Great Britain. Photo credit: Alinari / Art Resource, NY

Leonardo’s original portrait probably included Ginevra’s waist and hands. It was rectangular in shape instead of square and painted on a wood panel that was originally larger than what is seen today. At some point—possibly because of water damage — about six inches of the panel were cut off along the bottom and the right edge was trimmed.

Imagine how the portrait might have looked originally

How might Ginevra’s hands have been posed? What would the rest of her dress look like?

Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de’ Benci, c. 1474 / 1478, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund

Dotted line shows probable size of original portrait.

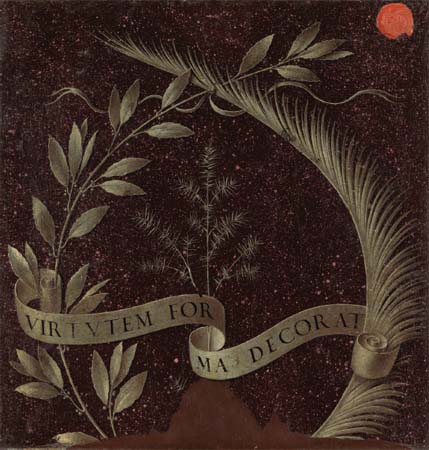

In addition to the front side of the portrait, Leonardo was asked to create an image on its reverse. On this “verso” side, Leonardo painted a scroll entwined around a wreath of laurel and palm branches, with a sprig of juniper in the center. While the front of the painting is a physical portrait of Ginevra, the reverse is an emblematic portrait: it uses symbols to describe her personality. The juniper sprig identifies Ginevra by name, and the laurel and palm branches represent two of her attributes: intelligence and strong moral values. The scroll bears a

Latin inscription: virtutem forma decorat. This translates as Beauty Adorns Virtue, which was Ginevra’s motto.

Originally, this painting might have hung from a ring on a wall or a piece of furniture so one side or the other could be seen. Today the painting is displayed in a freestanding case that shows both sides of the panel. It is thought to be Leonardo’s only double-sided painting.

Imagine what your own emblematic portrait might include (words, symbols, and so on).

Think about what you would illustrate about yourself. Which of your personality traits do you want people to remember? What characteristics make you unique?

Share these ideas with a family member or friend.

Create a double-sided self-portrait, with one side showing your physical appearance and the other side presenting an emblem of your personality and/or interests.

Leonardo da Vinci, Wreath of Laurel, Palm, and Juniper with a Scroll inscribed Virtutem Forma Decorat (reverse), c. 1474 / 1478, tempera on panel, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund

It is believed Prince Carl Eusebius of Liechtenstein purchased this painting after 1611. The red wax seal on the upper right corner of the panel was added in 1733, when the painting was inventoried as part of the collection of Prince Joseph Wenzel of Liechtenstein. Ginevra de’ Benci was purchased from Prince Franz Joseph II of Liechtenstein for the National Gallery’s collection in 1967.

Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755 – 1842) was so successful as a portrait painter in France during the late eighteenth century that she often had a waiting list! Why was she so popular? She pleased her clients by making them look attractive, with graceful poses and happy expressions. Her works mirrored fashionable life before the French Revolution of 1789.

Today Vigee Le Brun is known especially for her paintings of women and children. This group portrait depicts two of the artist’s close friends: the Marquise de Pezay, in the blue gown, and the Marquise de Rougé, the mother of the two young boys. The older boy, Alexis, gazes lovingly at his mother as he hugs her tightly, while the younger boy, Adrien, rests his head in her lap. Adrien wears a dress, which was typical for young boys at the time.

Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, Madame d’Aguesseau de Fresnes, 1789, oil on wood, National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Vigée Le Brun was interested in fashion, and she painted clothing with great detail and brilliant technique. She showed off her sitters’ wealth and elegance by depicting their luxurious garments and expensive accessories.

Imagine the textures of the fabric — the shimmering silks and iridescent taffetas of the flowing dresses worn by the Marquise de Pezay and the Marquise de Rougé. In another portrait, she meticulously painted the small embroidered gold circles on the white chiffon skirt of Madame d’Aguesseau de Fresnes. Vigée Le Brun carefully observed details, such as lace or gold edging, and she often selected her sitters’ attire. She even designed imaginative headdresses inspired by turbans from the Ottoman Empire.

Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, The Marquise de Pezay and the Marquise de Rouge with Her Sons Alexis and Adrien, 1787, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of the Bay Foundation in memory of Josephine Bay Paul and Ambassador Charles Ulrick Bay

Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait, c. 1781, oil on canvas, Kimbell Art Museum. In recognition of his service to the Kimbell Art Museum and his role in developing area collectors, the Board of Trustees of the Kimbell Art Foundation has dedicated this work from the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Kay Kimbell, founding benefactors of the Kimbell Art Museum, to the memory of Mr. Bertram Newhouse (1883 – 1982) of New York City.

Vigée Le Brun was born in Paris during the reign of Louis XV. Her father, an artist, introduced her to painting, but he died when she was just twelve years old. Mainly self-taught, Vigée Le Brun became a portrait painter to support her mother and brother. Talented and hard-working, she soon earned critical and financial success. She married an art dealer, and they had one daughter. In 1778 Vigée Le Brun was summoned to Versailles, the palace of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette. She became the queen’s favorite painter, and the two women were soon friends.

This was a time of political turmoil in France. Most of the common people resented the extravagant lifestyles of the noble classes. Finally, the tense situation exploded into the French Revolution, which brought ten years of violence. Many of Vigée Le Brun’s friends and patrons, including King Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette, were beheaded. As an artist associated with the royal court, Vigée Le Brun was also in danger, and she fled Paris in disguise. She spent the next sixteen years traveling in Italy, Germany, Austria, Russia, and England while painting portraits of wealthy families and royalty. Vigée Le Brun finally returned to France in 1805, after Napoleon Bonaparte had established a new empire and the revolution ended. She continued painting and was even asked to create a portrait of Napoleon’s sister. A celebrity in her own lifetime, Vigée Le Brun painted more than eight hundred portraits.

After Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, Marie-Antoinette, after 1783, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Timken Collection

Napoleon Bonaparte became the ruler of France in 1799 and crowned himself emperor in 1804. The artist Jacques-Louis David (1748 – 1825) painted this portrait when Napoleon was forty-three years old. Appointed by Napoleon to the important position of “First Painter,” David created many portraits of the ruler and depicted significant events during his reign. His paintings celebrated the emperor’s accomplishments, helped people become familiar with his policies, and played a large role in shaping the image of Napoleon as the new leader of France.

This nearly life-size portrait shows Napoleon in his study at the Tuileries palace. He appears to have just risen from his desk, rumpling the carpet as he pushed back his chair. Although it seems to be a casual, spontaneous picture of Napoleon at work, it is a precisely planned composition designed to convey a message about the emperor. Study the painting’s details. They provide clues that tell us Napoleon wanted to be identified with qualities of strength, leadership, and public service.

Two years after David completed this painting, Napoleon was defeated in battle and overthrown as emperor. David was banished from France due to his loyalty to Napoleon, and the artist spent the remaining years of his career in Brussels, Belgium.

Jacques-Louis David, The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries, 1812, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Military Leader

Lawmaker

Hard Worker

“By night I work for the welfare of my people, and by day, for their glory.” Napoleon Bonaparte

Vincent van Gogh (1853 – 1890) and Paul Gauguin (1848 – 1903) both experimented with the expressive possibilities of color and line to create distinct personal styles of painting. Working in France at the end of the nineteenth century, the two friends inspired each other during a nine-week period in the autumn of 1888.

In February of that year, Van Gogh moved to the peaceful town of Arles in the south of France. He dreamed of creating a “studio of the south” where a group of artists could work and live as a community. He invited his friend and fellow painter Gauguin to join him. Van Gogh transformed his yellow house into an artist’s studio in anticipation. Gauguin finally moved to Arles in October of 1888. Although they learned from each other’s techniques and produced many works side by side, Van Gogh’s stubborn nature and Gauguin’s pride and arrogance made their life together difficult. After nine weeks, a passionate argument caused Van Gogh to have a mental breakdown, and Gauguin returned to Paris. Despite the unhappy ending to the “studio of the south,” the two painters remained friends, and they wrote letters to each other until Van Gogh died two years later.

Even though they had different personalities, the two artists shared some things in common:

Both were essentially self-taught artists.

They both left city life in Paris in search of nature.

Both admired the brilliant color, simplified forms, and unconventional compositions of Japanese prints.

Each painted a variety of subjects, including landscapes, still lifes, and portraits.

Neither achieved fame until after his death, yet their works greatly influenced twentieth-century artists.

Although Van Gogh and Gauguin were influenced by impressionism, they were not satisfied with merely capturing the visual effects of nature and instead sought to create meaning beyond surface appearances, that is, to paint with emotion and intellect as well as with the eye.

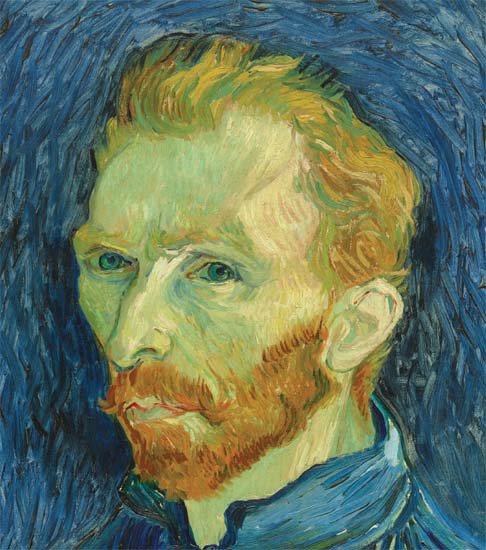

These self-portraits, painted in the year after Gauguin and Van Gogh lived together, provide a glimpse into their complex personalities and unique painting styles.

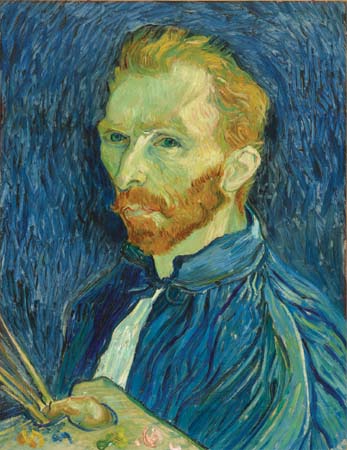

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1889, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney

“They say—and I am very willing to believe it — that it is difficult to know yourself — but it isn’t easy to paint yourself either.” Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, September 1889

After Van Gogh and Gauguin quarreled in 1888, Van Gogh became ill and spent many months recuperating in a hospital. This is the first self-portrait he created after he recovered. Van Gogh chose to paint himself wearing a blue painter’s smock over a white shirt and holding several paintbrushes and a palette. He was clearly asserting his identity as an artist, yet he also used intense colors to express his mood and feelings. He painted his gaunt face with yellow and green tones, and he set his vivid reddish-orange hair and beard against a deep violet-blue background. In a letter to his brother Theo, the artist described himself as looking “as thin and pale as a ghost” on the day he painted this portrait.

“For most I shall be an enigma, but for few I shall be a poet.” Paul Gauguin

Known for the way he applied paint thickly, Van Gogh gives a rich texture to the canvas by leaving each brushstroke visible as opposed to blending or smoothing them. He experimented with a variety of brushstrokes — dots, dashes, curves, squiggly lines, radiating patterns, woven colors, choppy short lines, and longer rhythmic strokes — that create a sense of energy in his work.

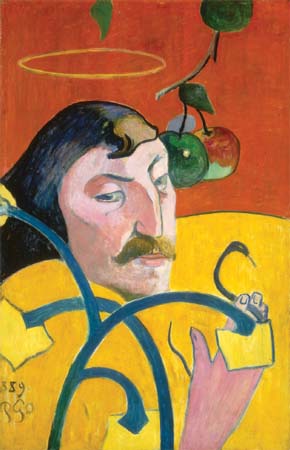

Paul Gauguin, Self-Portrait, 1889, oil on wood, National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection

Gauguin painted this self-portrait on a panel of a cupboard door in the dining room of the inn where he was staying in Brittany, France. Around his floating head, Gauguin arranged a golden halo, two apples, a dark blue snake, and a curling vine — objects that served as personal symbols of the artist’s mysterious, mystical world. Gauguin stated he had a “dual nature” and used the halo and snake to hint at his saintly and devilish sides. The apples allude to temptation.

Like Van Gogh, Gauguin manipulated color, line, and form to explore their expressive potential. His technique, however, was different. Instead of using energetic brushstrokes and thick paint, Gauguin applied his pigments thinly in smooth, flat patches of color, and outlined these broad areas of pure color with dark paint. He simplified shapes to the point of abstraction.

“Instead of trying to reproduce what I see before me, I use color in a completely arbitrary way to express myself powerfully.” Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, August 1888

Many artists are inspired by visiting new, exciting places. Both Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin left the city, seeking to renew themselves as artists in simpler, rural environments.

Compare these two landscapes. How are they similar? How are they different?

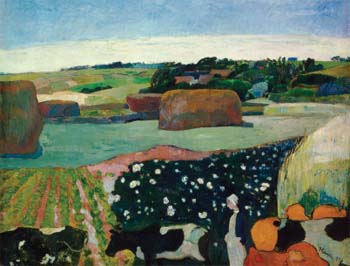

Gauguin in Brittany

In 1886 Gauguin first traveled to Brittany, a remote region of northwestern France famous for its Celtic heritage and rugged landscape. Gauguin painted Haystacks in Brittany in 1890. He simplified the landscape — fields, farm, haystacks, cow, and cowherd—into flat bands of color created with blocks of contrasting colors. Ever restless, Gauguin eventually found even Brittany to be too civilized. He left for Tahiti, an island in the Pacific Ocean, in 1891. Except for a brief return to France, he spent the rest of his life in French Polynesia.

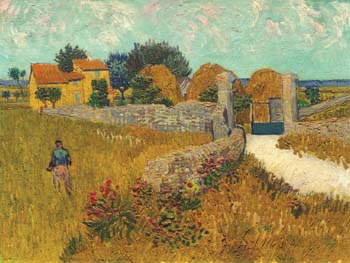

Van Gogh in Provence

In the winter of 1888, Van Gogh moved to Arles in the southern region of France known as Provence. There, the dazzling sunlight, golden wheat fields, and blooming sunflowers were far different from any place Van Gogh had experienced. He was inspired by the beauty of the landscape, and he often painted outdoors to capture the bright colors and intense sunshine.

Paul Gauguin, Haystacks in Brittany, 1890, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of the W. Averell Harriman Foundation in memory of Marie N. Harriman

Vincent van Gogh, Farmhouse in Provence, 1888, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Collection

Summer was Van Gogh’s favorite season, and he made many paintings depicting wheat fields and farms during the harvest. In Farmhouse in Provence, painted in the summer of 1888, haystacks are piled high behind a stone gate, and a farmer walks through the tall grass toward a farmhouse. The golden field seems to shimmer in the sunlight. Van Gogh energized his paintings by pairing complementary colors—the blue mountains on the horizon with yellow-orange haystacks and rooftop; the pink-purple clouds with the blue sky; the red and green flowering plants—to convey the heat of the strong southern sun.

“Don’t copy nature too closely. Art is an abstraction; as you dream amid nature, extrapolate art from it.” Paul Gauguin

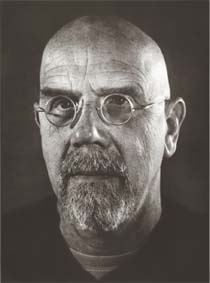

American artist Chuck Close (born 1940) is famous for painting giant portrait heads. He’s also well known for facing some big challenges in his life.

Growing up, Close had severe learning disabilities that made it difficult for him to read. His talent for drawing and painting helped him to compensate for his academic struggles. He impressed his teachers by creating elaborate art projects to show he really was interested in his school subjects.

In 1988, when he was almost fifty years old, Close suffered a severe spinal artery collapse. As a result, he has only partial use of his arms and legs, and he has to rely on a wheelchair. He now uses a chair lift and motorized easel that raises, lowers, and turns the canvas to allow him to work on all parts of a painting.

Chuck Close, Self-Portrait/Photogravure, 2004 / 2005, photogravure on Somerset Textured white, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Graphicstudio / University of South Florida

Chuck Close at work on Elizabeth, 1989 (photo: Bill Jacobson) © Chuck Close, courtesy The Pace Gallery

“Almost every decision I’ve made as an artist is an outcome of my particular learning disorders. I’m overwhelmed by the whole. How do you make a big head? How do you make a nose? I’m not sure! But by breaking the image down into small units, I make each decision into a bite-size decision. I don’t have to reinvent the wheel every day. It’s an ongoing process. The system liberates and allows for intuition. And, eventually I have a painting.” Chuck Close

Chuck Close paints close-up views of his family and friends. Every detail, every wrinkle, every strand of hair is magnified. People in Close’s portraits don’t show much expression or personality, much like a passport or driver’s license photo.

Fanny / Fingerpainting depicts Fanny Lieber, the artist’s grandmother-in-law. Fanny was the only member of her large family to survive the Holocaust, and Close admired her strength and optimism.

Chuck Close, Fanny/Finger-painting, 1985, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Lila Acheson Wallace

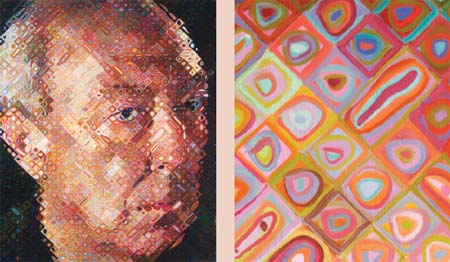

Close typically starts with a photograph. Instead of asking someone to sit in front of him while he paints, a slow process that could take days or months, Close takes several photographs of his subject. He then carefully selects one photo. He uses a grid to divide it into smaller units and to maintain the proportional scale between the photo and the much larger canvas. Often applying a grid to the canvas as well, he transfers the image square by square from photo to canvas. It’s an exacting and painstaking process that Close has used throughout his career.

Although Close continues to employ his photo-grid process, he always looks for new challenges. At different times he has experimented with an airbrush, colored pencils, watercolor, fragments of pulp paper, printing inks, and oil and acrylic paints to create his portraits. He even used fingerprints! For Fanny /Fingerpainting, Close applied the paint to the canvas with his fingers, pressing harder to apply more pigment and pressing lightly for less. He placed fingerprints densely in some places and more sparingly in other areas. From a distance, the painting looks like a black-and-white photograph; up close her face dissolves into a sea of fingerprints.

Chuck Close, Fanny, 1984, polaroid photograph mounted on board with masking tape border; squared in ink for transfer, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund

At 8 ½ by 7 feet, the painting of Fanny is more than five times larger than the photograph.

“I think problem-solving is generally overstressed. The far more important thing is problem creation. If you ask yourself an interesting question, your answer will be personal. It will be interesting just because you put yourself in the position to think differently.” Chuck Close

Compare Jasper and Fanny/Fingerpainting

How are they similar? How are the two paintings different? Look closely and list as many similarities and differences as you can find.

Fanny /Fingerpainting was created before Close became paralyzed. After his spinal artery collapse, Close lost fine motor control in his hands, and he could no longer make fingerpaintings. For Jasper and similar paintings, Close attached a paintbrush to his hand and moved his arm to apply the paint onto the canvas.

Chuck Close, Jasper, 1997 – 1998, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Ian and Annette Cumming

The detail above comes from Jasper’s forehead.

“There’s a real joy in putting all these little marks together. They may look like hot dogs, but with them I build a painting.” Chuck Close