“These pictures are all the more amazing as nobody had ever created anything similar.” Gregorio Comanini, II Figino, 1591

Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526 – 1593) was born into a family of painters in the northern Italian city of Milan. The city was considered the cradle of naturalism, a mode of artistic expression based on the direct observation of nature. This approach to art was shaped by Leonardo da Vinci, whose work Arcimboldo likely studied in Milan.

In 1563, at the age of thirty-six, Arcimboldo left Italy to work in the imperial courts of the Habsburg rulers, first for Maximilian II in Vienna and then for Rudolf II in Prague. He served as court painter for twenty-five years, creating portraits of the imperial family. Like other artists of his time, he designed tapestries and stained glass windows, and created theater costumes for the elaborate festivals and masquerades he organized at the court. However, Arcimboldo remains best known for the highly original “portraits” he composed by imaginatively arranging objects, plants, animals, and other elements of nature.

To celebrate the reign of Emperor Maximilian II, Arcimboldo presented two series of composite heads: The Seasons and The Elements. In The Seasons (Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter), created in 1563, Arcimboldo combined plants associated with a particular season to form a portrait of that time of year. The series was extremely popular in the Habsburg court, and Arcimboldo reproduced it several times so the emperor could send versions to friends and important political figures. Three years later he completed a series on the four elements (Earth, Air, Fire, and Water). Arcimboldo also made witty composite portraits of different professions, such as a librarian, jurist, cook, and vegetable gardener, using objects associated with each occupation. In these innovative works, Arcimboldo fills the paintings with dense details that come together harmoniously to create a human form.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Water, 1566, oil on limewood, © Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Austria

From The Elements series, this painting combines more than sixty different fish and aquatic animals.

When Arcimboldo arrived at the court of Emperor Maximilian II, he found his new patron was passionately interested in the biological sciences of botany and zoology. The study of flora and fauna grew as a result of the voyages of exploration and discovery that were undertaken to the New World, Africa, and Asia in the sixteenth century. Explorers returned with exotic plants and animals that created an explosion of European interest in the study of nature. Maximilian transformed his court into a center of scientific study, bringing together scientists and philosophers from all over Europe. His botanical gardens and his zoological parks with elephants, lions, and tigers caused a sensation.

As court painter to the emperor, Arcimboldo had access to these vast collections of rare flora and fauna. His nature studies show his skill and precision as an illustrator and his knowledge as a naturalist—but Arcimboldo went beyond illustration by building fantastic faces out of the natural specimens he observed. His paintings not only demonstrate a unique fusion of art and science, but they also provide an encyclopedia of the plants and animals that Maximilian acquired for his botanical garden and menagerie.

Maximilian displayed Arcimboldo’s paintings of the seasons and elements in his Kunstkammer, a special “art chamber” dedicated to his collections of marvelous and curious things. Along with works of art, he collected Greek and Roman antiquities, scientific instruments, precious gems, fossils, and interesting shells. Arcimboldo’s paintings fit right in among the emperor’s many prized possessions.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, The Librarian, 1562, oil on canvas, Skoklosters Castle (photo: Samuel Uhrdin)

In this portrait of the court historian Wolfgang Lazius, the artist used an open book for his full head of hair, feather dusters for his beard, keys for his eyes, and bookmarks for his fingers.

Look closely at Four Seasons in One Head. A gnarled and knotty tree trunk creates the figure’s head and chest, representing the winter season. Two holes in the trunk form the eyes, a broken branch serves as a nose, and moss and twigs are the beard. Spring flowers decorate the figure’s chest. Summer is indicated by the cherries that form the ear, the plums at the back of the head, and the cloak of straw draped around the shoulders. Apples, grapes, and ivy, the fruit and plants of autumn, top the head. On a branch among the apples, Arcimboldo inscribed his name in the wood beneath the bark that has been stripped away: “ARCIMBOLDUS F” (F is for fecit, which means “made this” in Latin).

This is one of the last paintings that Arcimboldo created after he returned to Milan from the Habsburg court in 1587. Perhaps he considered it a self-portrait in the “winter” of his life, brooding over his bygone seasons.

Imagine that this portrait could talk. What stories might it tell?

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Four Seasons in One Head, c. 1590, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Paul Mellon Fund

Explore Arcimboldo’s The Seasons. List at least five things the artist incorporated into the paintings to suggest each season. How does each painting remind you of a particular season?

Compare: How are the four paintings similar? How are they different?

Create a composite portrait of a season

You will need:

A cardboard, wood, or canvas surface

Clear-drying glue, such as PVA or Mod Podge

A brush

Collage materials — newspapers, magazines, decorative papers, stickers, etc.

Choose a season for the subject of your work. Collect collage materials that remind you of that season, such as twigs, leaves, and photographs of activities that you enjoy at that time of year.

Start by making an outline of a human profile on your board or canvas, indicating generally where the eyes, nose, ears, and mouth might be. This will serve as a guide as you arrange your collage materials.

Cut out and arrange parts for your collage. Experiment with overlapping pieces and turning them in various directions. Consider how different shapes can be combined to create a human head. Keep in mind your color palette and how it can help communicate the mood or feel of the season. When arranging collage pieces, start with larger shapes to cover the area of the head, then use smaller pieces to create details and facial features.

Once you have arranged the collage elements, begin to glue them down. Brush glue on the underside to adhere to the board or canvas. When you are finished, brush a thin layer of glue on top of the entire work to prevent the edges from curling.

Try this again with a different subject. Consider choosing a profession, a school subject, or a holiday. You might even want to create a series, as Arcimboldo did.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Winter, 1573, oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris, France (photo: Jean-Gilles Berizzi). Photo credit: Réunion Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY

Giuseppe Arcim-boldo, Summer, 1573, oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris, France (photo: Jean-Gilles Berizzi). Photo credit: Réunion Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Spring, 1573, oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris, France (photo: Jean-Gilles Berizzi). Photo credit: Reunion Musees Nationaux / Art Resource, NY

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Autumn, 1573, oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris, France (photo: Gérard Blot). Photo credit: Réunion Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY

Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer (1632 – 1675) is famous for his paintings of intimate, quiet scenes of everyday life in the seventeenth century. His paintings are especially treasured because they are so rare — only thirty-five of his paintings survive, and none of his personal writings or drawings has been found.

Much about Vermeer’s life and career remain a mystery. He lived most of his life in Delft, a wealthy trading city in the Dutch Republic. His father was an innkeeper and art dealer, so Vermeer must have been surrounded by art as a child. It is not known where or with whom he trained, but his early work was as a history painter, specializing in scenes from ancient history, mythology, religion, and literature. Vermeer soon developed a special interest in genre scenes. In these images of daily life, he painted small-scale views of domestic scenes, such as musical concerts or women writing letters. Since these are not portraits of specific people, his paintings tend to have a timeless, universal quality.

After his death at the age of forty-three, Vermeer’s reputation as an artist faded, probably because he left behind few works. After Vermeer’s work was “rediscovered” in the nineteenth century, his masterful technique, delicate use of light and shadow, and poetic simplicity became greatly admired.

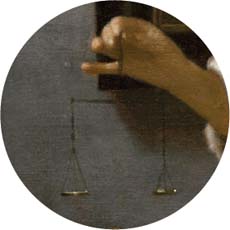

In Woman Holding a Balance, a woman stands quietly, looking down at a perfectly balanced scale. She wears an elegant blue jacket trimmed with white fur, and she stands in front of a table that holds coins, pearls, gold, and other precious objects. A large painting of a religious scene hangs on the wall behind her.

This painting presents themes and characteristics found in many paintings by Vermeer.

A moment in time: It captures a moment that seems to be frozen in time forever. His works leave us wondering: What might happen next?

Looking into a private world: This woman is lost in her own thoughts as she gazes at the balance held in her right hand. Vermeer presents a quiet, intimate scene of a solitary figure. His works make us curious: What might the woman be thinking or feeling? Why is she holding the balance?

Sunlight and shadows: Daylight streaming through the window on the left casts a diagonal beam of light across the scene. The woman’s face and hands are illuminated, and the pearls and gold glimmer in the light. Meanwhile, the rest of the scene is dark with shadows, creating a sharp contrast.

A limited palette of colors: Vermeer created his tranquil paintings by using just a few tones and shades, including yellow, ochre, brown, gray, and ultramarine blue. These color tonalities give the painting a visual harmony.

Woman Holding a Balance shows a scene of everyday life, but it is also an allegory—it uses a story and characters to represent a larger idea about the moral and spiritual aspects of being human. Common in Dutch genre scenes of the seventeenth century, allegories reminded viewers not to let the wealth and prosperity of the times distract them from important spiritual goals.

Pearls, gold jewelry, and coins—references to earthly beauty and wealth — spill from a jewelry box and spread across the table in front of her. The large painting hanging behind her shows the Last Judgment, part of the end of the world as described in the Bible. Paintings of the Last Judgment remind viewers to consider their actions and decisions carefully because they will be assessed and weighed at the end of time. Vermeer added one more important object to the scene: a small framed mirror that hangs on the left wall directly opposite the woman’s face. Artists often used mirrors to symbolize self-reflection or self-awareness.

Through this tranquil painting, Vermeer emphasizes that riches and wealth are not the most important things in life. Instead, people should lead a balanced, harmonious life, one spent in moderation and self-reflection, and weigh their worldly possessions with their spiritual life.

Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance, c. 1664, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Widener Collection

Both A Lady Writing and Woman Holding a Balance show moments of thoughtful attention. Consider other similarities as well as differences between the paintings.

The lady at her writing desk looks as if she has been interrupted. What might she be thinking? At whom might she be looking? To whom might she be writing?

Many of the same objects—pearl necklace and earrings, jewelry box, fur-trimmed coat, table draped with blue fabric, chair with lion head finials—appear in Vermeer’s paintings. This leads art historians to believe that he had these props in his studio and reused them to compose different scenes.

Johannes Vermeer, A Lady Writing, c. 1665, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Harry Waldron Havemeyer and Horace Havemeyer, Jr., in memory of their father, Horace Havemeyer

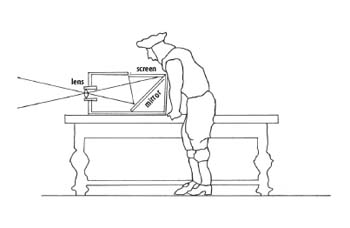

People have long wondered how Vermeer was able to create paintings that look like snapshots. Before photography was invented in the nineteenth century, it was unusual for paintings to have this quality. This has led some to believe that Vermeer may have studied light effects through a camera obscura (Latin for “dark room”). Used since the Renaissance, this pinhole device projects an image onto a wall surface with the aid of a lens. Scientists and mathematicians utilized it for astronomical observation, and some artists employed it to aid in topographical drawing. With the study of optics and the development of lenses (for microscopes and telescopes) in the Dutch Republic during the seventeenth century, the camera obscura became yet another way for artists and scientists to study the world during this time of great exploration and discovery.

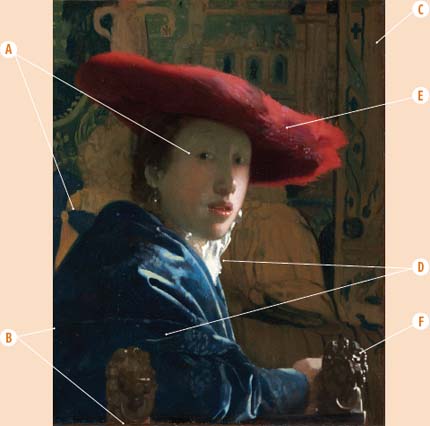

Although he did not paint in a darkened room and copy images from a camera, Vermeer noted the particular effects of the camera obscura and adeptly translated them in his compositions. Girl with the Red Hat is a good example of some of the phenomena observed through a camera. The girl, wearing a large “Turkish” style hat and draped in blue fabric, is seated in a chair (with lion head finials similar to the one in A Lady Writing ). She turns around as if she’s been interrupted, her mouth open as if she is about to speak.

Effects of the camera obscura:

A focused and unfocused (blurry) areas

B composition: figures and objects are cropped at the edge of the picture, which occurs when you look at a scene through a lens and box

C flattened space (shallow depth of field): it’s hard to tell that a tapestry is on the wall behind her, and you don’t feel a great sense of space in the room

D sharp contrasts of light and shadow

E intensification of color

F diffused highlights (halation): this occurs when light hits a reflective surface. Vermeer often painted these areas with dabs of white to exaggerate their effect; up close they look abstract.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl with the Red Hat, c. 1665 / 1666, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Andrew W. Mellon Collection

The diagram to the left shows a simple camera obscura: a box with a lens, mirror, and glass screen. Light travels through the lens, reflects off the surface of the mirror, and projects an image from the world onto the glass.

During his long career, Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775 – 1851) painted a wide range of subjects: seascapes, topographical views, historical events, mythology, modern life, and imaginary scenes. Turner’s innovative focus on light and the changing effects of atmosphere made his landscapes enormously popular and influential.

Born in London, Turner was the son of a barber who sold the boy’s drawings by displaying them in the window of his shop. Turner decided to become an artist at the age of fourteen, and he enrolled in the school of the Royal Academy of Art, the leading art society in Great Britain. Ambitious as well as talented, he was elected the youngest member of the Royal Academy eight years later, at the age of twenty-two. In 1807 he was appointed professor of perspective at the Royal Academy, a position he held for thirty years. His father assisted him in the studio for many years.

Although he lived in London all his life, Turner traveled extensively across Britain and throughout Europe. By closely observing nature and sketching outdoors, he recorded his visual experience of landscapes and his emotional responses to them. His sketchbooks served as a type of memory bank for ideas he used months and even years later. Three hundred of Turner’s sketchbooks still exist.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Self-Portrait (detail), c. 1799, Tate, Bequeathed by the Artist, 1856. © Tate, London 2007. Photo credit: Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Turner visited Tyneside, a town near Newcastle in northeast England, in 1818, but he did not paint Keelmen Heaving in Coals by Moonlight until 1835, almost twenty years later. This scene shows a view of Tyneside’s busy harbor. Coal was the essential source of power at the time of the Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century, and the Newcastle region was the mining and industrial center of Britain.

The shallow Tyne River flows through rich coal fields, and flat-bottomed barges, called keels, transported the coal. Keelmen ferried coal from mines up the river to the mouth of the harbor, where they shoveled the coal into specially designed ships known as colliers. These boats were loaded at night so they could sail with the morning tide down the coast to London. Turner depicts keelmen transferring coal in the glow of moonlight and torchlight.

Although Turner’s painting describes a scene of contemporary trade and industry, light is the true subject of his composition. Light from the full moon illuminates the cloudy sky and glitters on the calm water. Dark boats and silhouetted figures frame the view and draw attention across the distance and out to sea. Capturing the drama of a night sky over water, Turner makes nature a central focus of this work.

To convey mood and atmosphere, Turner also experimented with painting techniques. In a rather unconventional way, he applied paint with a palette knife, a tool usually reserved for mixing colors.

Turner painted some areas of Keelmen Heaving in Coals by Moonlight more thickly than others, such as the silvery white moon and the yellow-orange torchlights. In this technique of applying paint thickly to a canvas, called impasto, the artwork often retains the mark of the brush or palette knife. Turner’s heavy application and thick paint create a textured surface that allows the raised areas on the canvas to catch light.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Keelmen Heaving in Coals by Moonlight, 1835, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Widener Collection

Turner traveled abroad several times, touring Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, France, Austria, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy. He filled his sketchbooks on these summertime trips, and he returned home to work on oil paintings during the winter. In his luminous landscapes that combine memory and imagination, Turner describes weather conditions as if he had made his oil paintings on the spot.

Turner’s imagination was most captivated by the Italian city of Venice. Its location on the water provided numerous opportunities for the artist to explore light and color. The two paintings here, made nearly a decade apart, illustrate the development of Turner’s artistic style.

The earlier work, Venice: The Dogana and San Giorgio Maggiore, shows the bustling activity along and in the Grand Canal, as gondolas transport goods and people. Turner features two important sites: the church of San Giorgio Maggiore and the Dogana, or Customs House. The water sparkles with radiant sunlight and reflects the buildings and boats.

In The Dogana and Santa Maria della Salute, Venice, Turner’s later style is a study of atmospheric effects. Details of architecture, boats, and people are minimized, and the light seems to evaporate the solid forms of the buildings and boats. Few of Turner’s contemporaries understood his later works with their poetic haziness, but these paintings greatly influenced future generations of artists.

Paint with a palette knife

Challenge yourself to create a landscape or cityscape scene using only a palette knife, a traditional tool usually used for mixing paint. Experiment with it, and find out how many different ways you can use it.

You will need:

Thick acrylic paint or tempera thickened with wallpaper paste

Mounted canvas, foamboard, or white cardboard

A metal or plastic palette knife

Experiment

Reflect: How did this technique feel? What were its challenges? What effects did you create that you wouldn’t have been able to do with another tool?

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Venice: The Dogana and San Giorgio Maggiore, 1834, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Widener Collection

At the “especial suggestion” of a British textile manufacturer, Turner devised this Venetian cityscape as a symbolic salute to commerce. Gondolas carry cargoes of fine fabrics and exotic spices. On the right is the Dogana, or Customs House, topped by a statue of Fortune. Keelmen was painted as a companion piece to this picture. When displayed together, the two paintings present a comparison between great maritime and commercial powers, Venice and Great Britain.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, The Dogana and Santa Maria della Salute, Venice, 1843, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Given in memory of Governor Alvan T. Fuller by The Fuller Foundation, Inc.

“A painter paints to unload himself of feelings and visions.” Pablo Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (1881 – 1973) was one of the most inventive artists of all time. He continually searched for fresh ways to represent the world, and he is admired for his experimentation with different styles, materials, and techniques. The years 1901 to 1906 are often described as Picasso’s Blue and Rose periods because he was exploring the way color and line could express his ideas and emotions.

Born in southern Spain, Picasso studied at art academies in Barcelona and Madrid. He first visited Paris, then the center of the art world, in 1900 at the age of nineteen, and he was captivated by the vibrant city and its museums and art galleries. Four years later Picasso settled in Paris, and France became his adopted home.

Pablo Picasso at Mont-martre (detail), Place Ravignan, c. 1904, Musée Picasso, Paris. Réunion Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, NY (photo: RMN-J. Faujour)

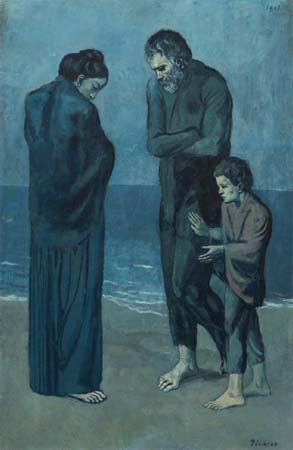

Being an immigrant to Paris, Picasso sympathized with the city’s poor and hungry people, with their struggles and their sense of isolation. He also felt great sorrow over the death of his best friend. These feelings literally colored his works. From 1901 to 1904 Picasso experimented with using dark, thick outlines to create figures and shapes on his canvas. He filled in the outlines with lighter and darker tones of blue. The Tragedy, one painting from his Blue period, shows three unnaturally tall, thin figures on an empty beach.

Consider: How might the people be feeling?

Pablo Picasso, The Tragedy, 1903, oil on wood, National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection © 2013 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A few years later, Picasso began to paint with lighter and more delicate colors, such as rosy pinks, reds, and warm browns. He also discovered a new subject of interest: the circus. He was fascinated by the clowns and acrobats who performed in the Cirque Médrano, which was based in Montmartre (his neighborhood in Paris). Picasso felt a strong connection with these saltim-banques, or street performers. They were all outsiders who worked here and there, making art. The entertainers who appear in his paintings and drawings, however, are not shown performing. Instead, Picasso presents them in quiet, unexpected moments. These years, from late 1904 to early 1906, are called Picasso’s Rose or circus period.

“Colors, like features, follow the changes of the emotions.” Pablo Picasso

Family of Saltimbanques shows a circus family in a sparse setting. A harlequin, or jester, wears a diamond-patterned suit. He holds the hand of a young girl in a pink dress carrying a basket of flowers. A large clown in a red costume and two young acrobats — one holds a tumbling barrel — complete the circle. A woman with a hat decorated with flowers sits off to one side.

Wonder: What is the relationship among the people?

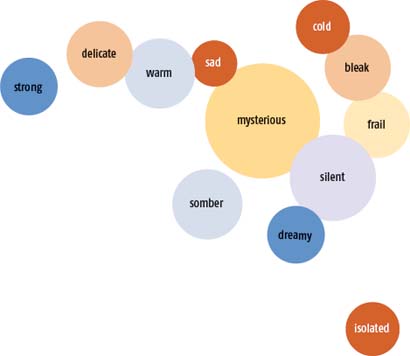

Compare: How are these two paintings similar? How are they different? Which words best describe each painting?

Pablo Picasso, Family of Saltim-banques, 1905, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection © 2013 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

To better understand how artists communicate feelings, experiment with color and contour line to create a “moody” watercolor resist painting.

You will need: Crayons

Watercolor paints and brush

Watercolor paper

In the works from his Blue and Rose periods, Picasso explored line and color. He used dark, heavy outlines — called contour lines—to define the figures and shapes in his paintings. He then limited his palette to only a few colors so he could focus on the emotional quality of the scene.

Ask your family or friends to strike a pose for you. Take some time to study the poses. Try tracing the outlines of the figures in the air with your finger. On a piece of water-color paper, use a pencil to draw the contour lines of the figures and objects you see. Trace over your lines with a crayon. Press hard to make the lines thick.

Next, decide which mood or emotion you wish to communicate in your painting. Choose two colors that might best express that feeling. Use this limited watercolor palette to paint over the crayon lines. Cover the entire paper with color. Create light and dark shades by adding more or less water to the paint. Mix the two colors together to create a third color.

Discover: The lines made with the wax crayon will show through, or resist, the watercolor. This results in a painting made of both lines and colors.

Pablo Picasso, Juggler with Still Life, 1905, gouache on cardboard, National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection © 2013 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

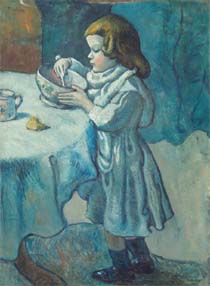

Pablo Picasso, Le Gourmet, 1901, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection © 2013 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Joan Miró (1893 – 1983) was born, educated, and trained as an artist in Barcelona, Spain. Although the art scene in Barcelona was lively, Miró moved to Paris in 1920, seeking a more cosmopolitan environment. There he met a fellow Spanish artist, Pablo Picasso. Miró was inspired by the interlocking shapes and facets of Picasso’s cubist art. Another influence on Miró’s style was his contact with the many other avant-garde artists — particularly Dada and surrealist poets—who lived and worked in Paris.

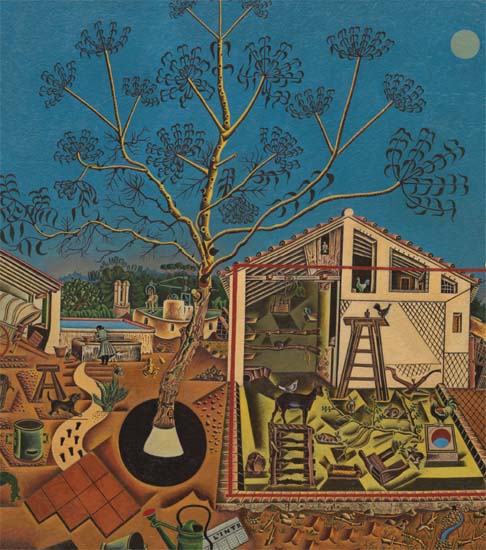

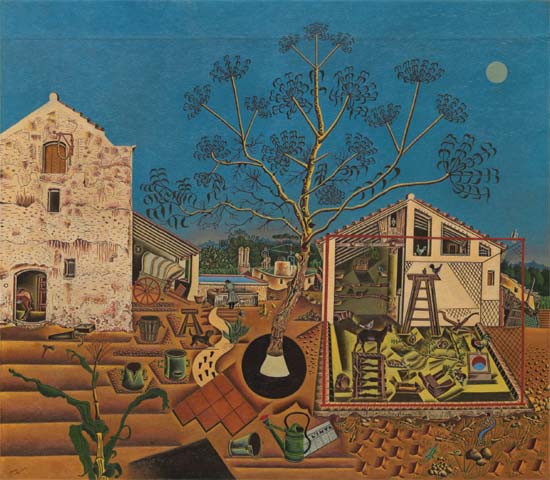

At the same time, Miró remained deeply attached to Catalonia, the northeast corner of Spain where he grew up. Each summer he returned to his family’s farm in Montroig, a village near Barcelona. Parts of the landscape of Catalonia—plants, insects, birds, stars, sunshine, the moon, the Mediterranean Sea, architecture, and the countryside — appear in Miró’s art throughout his long career. He began The Farm in Montroig in the summer of 1921. The artist continued to work on it in Barcelona, and he completed it nine months later in his studio in Paris.

American writer Ernest Hemingway — Miró’s friend and occasional sparring partner at a boxing gym in Paris — purchased The Farm as a birthday present for his first wife, Hadley, in 1925 or 1926. The painting later hung in Hemingway’s homes in Key West, Florida, and Havana, Cuba. The author once wrote, “Miró was the only painter who had been able to combine in one picture all that you felt about Spain when you were there and all that you felt when you were away and could not go there.”

Joan Miró in his Barcelona studio (detail), 1914, (photo: Francesc Serra), Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona - Arxiu Fofogràfic

This painting is a “portrait” of a cherished place, an inventory of Miró’s life on his farm in Catalonia.

Look closely to find:

A large eucalyptus tree (its dark leaves are silhouetted against the brilliant blue sky)

Footsteps along a path

A barking dog

A woman washing clothes at a trough, with her baby playing nearby

A donkey plodding around a millstone Mountains

Families of rabbits and chickens in a coop

A pig peeking through an open door

A goat with a pigeon perched on its back

A lizard and snail crawling amid grass and twigs

Buckets, pails, and watering cans littering the yard

A farmhouse with a horse resting inside and a covered wagon propped outside

Wonder

What time of day is it? Is that the sun or a full moon in the sky?

Whose footprints are those? Why do they suddenly end?

What might be making the dog bark?

Joan Miró, The Farm, 1921 – 1922, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mary Hemingway

“This picture represents all that was closest to me at home, even the footprints on the path by the house…I am very much attached to the landscape of my country. That picture made it live for me.” Joan Miró

Although Miró never officially joined the surrealist group, André Breton, its founder, remarked, “Miró is the most surrealist of us all.” Surrealist artists tried to release the creative power of the subconscious mind by making images in which the familiar meets the fantastic. Miró wanted to depict the things he envisioned in his mind as well as those he saw with his eyes. This way, he could demonstrate the power of imagination to transform reality.

The Farm is an example of how Miró made the ordinary extraordinary. The scene is both real and unreal. It feels familiar, yet unfamiliar. Daily events in the farmyard are meticulously rendered, each element carefully observed and precisely described, yet the overall effect is strangely dreamlike. Miró’s style — fanciful and playful, while wonderfully detailed and thoughtfully arranged — creates a kind of magical realism.

José Pascó was Miró’s teacher at the Barcelona School of Fine Arts. He encouraged his young pupil to experiment. Years later, in 1948, Miró recalled, “Pascò was the other teacher whose influence I still feel…. Color was easy for me. But with form I had great difficulty. Pascò taught me to draw from the sense of touch by giving me objects which I was not allowed to look at, but which I was afterwards made to draw. Even today … the effect of this touch drawing experience returns in my interest in sculpture: the need to mold with my hands, to pick up a ball of wet clay like a child and squeeze it. From this I get a physical satisfaction that I cannot get from drawing or painting.” Pascò tried to stimulate Miró’s senses and make him become more aware of his surroundings. He wanted his student not only to rely on what he saw but also to work from what he felt and imagined.

Experiment: Make a drawing of something that you cannot see!

You will need:

Two large paper bags (a grocery bag will do)

Paper

Colored pencils, crayons, or markers

This activity requires two people. Each of you should secretly choose a safe object — a stuffed animal, toy, flower, hairbrush, spoon, keys, an item of clothing — and place it in a paper bag so the other person cannot see it. (Don’t choose a dangerous object with sharp edges.)

Feel: Take turns reaching into each other’s bag and touching the mystery object inside. Use your hands and your imagination, but not your eyes. Feel the entire object from front to back, top to bottom, and side to side. Think about the object’s size and shape. Describe its textures. Is it smooth, bumpy, soft, rough, hard, or a combination of textures? Does it remind you of anything?

Imagine: Close your eyes, keeping your hand on the mysterious object in the bag. Imagine that this object is a new species. Where might it live? What might it eat? What sounds would it make? Does it fly, swim, crawl, or run? Imagine that the object came from another planet. What could it be? Imagine that the object is a building. What is its purpose? What or who is inside? What is the environment like around it? Imagine that the object is a kind of food. How would it taste?

Next, without looking in the bag, make a drawing inspired by the object. Describe the object’s shape and texture as well as ideas that formed in your imagination. Draw without stopping to worry about the final result. Surprise yourself!

Reflect: How did this experience help you think about the object differently?

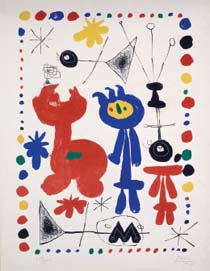

Joan Miró, Shooting Star, 1938, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Joseph H. Hazen. Copyright © 1998 Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Joan Miró, Figure and Birds, 1948, color lithograph, Paris 1974, no. 231, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine

Diego María Rivera (1886 – 1957) was born in the small town of Guanajuato in central Mexico. He moved with his family to Mexico City in the early 1890s. Both of his parents were school teachers. As a way to encourage his son’s artistic talent, Rivera’s father covered the walls of the boy’s room with canvas so that he could draw on them. By the age of twelve, Rivera had already finished high school, and he entered San Carlos Academy, the national art school of Mexico. Rivera studied works by Mexican painters, collected Mexican folk art, and traveled great distances to see the art of Mexico’s ancient Maya and Aztec cultures. In this way he gained a deep respect for his country’s traditions.

From 1910 to 1920, a decade marked by the Mexican Revolution and World War I, Rivera resided in Europe on a grant of money from the government of Mexico. By the age of twenty-one he had lived and worked in Spain, Italy, and France. He was inspired by Spanish art, wall frescoes from the Italian Renaissance, and the bold new style of modernism. In Paris, Rivera met many artists, including Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. They were developing a new artistic style called cubism, which was a daring way of visualizing three-dimensional objects on a flat surface, such as paper or canvas. Picasso and Braque challenged themselves to show several views or sides of an object simultaneously. This cubist technique makes objects in their works look broken up and then reassembled.

Diego Rivera, Self-Portrait (detail), 1941, Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, MA. Gift of Irene Rich Clifford

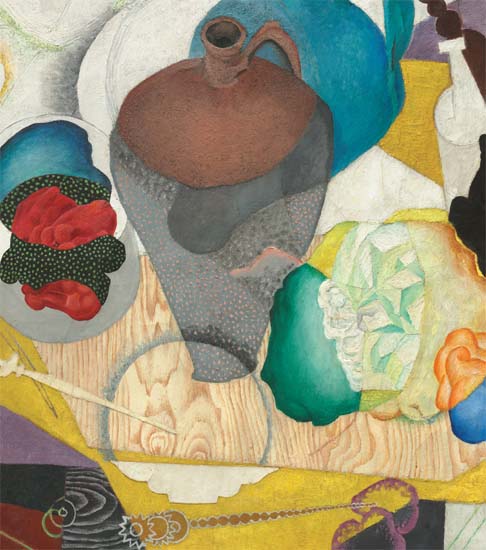

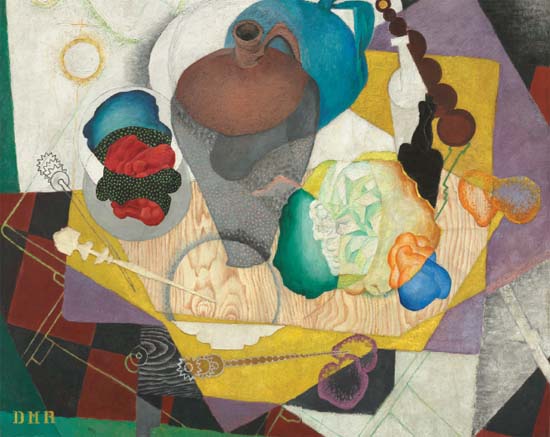

In his own experimentation with cubism, Rivera painted No. 9, Nature Morte Espagnole (Spanish Still Life) in boldly simplified shapes. Look for circles, triangles, and rectangles. Which objects do you recognize? Overlapping rectangles show a table viewed both from above and the side. Where did Rivera paint patterns to imitate the wood grain of the table top?

A large earthenware jug at the center of the table casts a blue-green shadow. Surrounding it are glass bottles, fruits, and vegetables, all shown from multiple views. On the left, Rivera included a molinillo, small wooden whisk used to mix the ancient Mexican drink chocolate de agua. For hundreds of years, Mexicans have used molinillos to whip hot chocolate into a frothy drink. When making his cubist paintings in Europe, Rivera often included things that reminded him of México. Can you find all three views of the molinillo?

Molinillo (photo: Donna Mann, National Gallery of Art)

Rivera varied colors and textures to make his paintings more visually interesting. His cubist compositions are distinctive for their bright colors. To add texture, he applied paint thickly in some places or covered areas with little dabs. Sometimes he mixed sand or sawdust into his oil paint to give it a rough texture. Rivera used a variety of textures in No. 9, Nature Morte Espagnole. The paint is so thick at the mouth of the jug that it resembles real clay. It almost seems water could be poured through the opening!

Diego Rivera, No. 9, Nature Morte Espagnole, 1915, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Katharine Graham

“My cubist paintings are my most Mexican.” Diego Rivera

When he returned to Mexico, Rivera combined the painting techniques he had learned in Europe with his passion for his homeland. He focused on the history and daily life of ordinary Mexicans, particularly factory workers, farmers, and children. In the 1920s and 1930s Rivera became famous for the large murals he painted on the walls of public buildings. He believed art should be seen and enjoyed by all people. Through his murals he told powerful stories about the struggles of the poor, and he emphasized the history and diverse peoples of Mexico. When he died in 1957, Rivera was honored for creating a modern Mexican art that celebrated his country’s native traditions.

Diego Rivera, Friday of Sorrows on the Canal at Santa Anita, from A Vision of the Mexican People, 1923 – 1924, mural. Secretaria de Educacion Publica, Mexico City © 2013 Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums Trust / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo credit: Schalkwijk / Art Resource, NY

This mural is part of a cycle showing the history of the Mexican people from the time of the great Aztec civilization.

Diego Rivera’s No. 9, Nature Morte Espagnole is an example of his early experimentation with cubism. Flowers, fruit, books, musical instruments, bottles, bowls, or other objects are carefully arranged in still-life paintings. Some artists paint these objects so convincingly that they fool your eye into thinking they’re real. Other painters, such as the cubists, make it difficult to identify the items.

Cubism was pioneered in the early 1900s by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, who were influenced by Paul Cézanne’s use of multiple viewpoints in a single painting. The way cubists represented the world was considered to be radical: they fractured form, shifted viewpoints, confused perspective, and flattened volume. Their work often resembled a collage and sometimes even included collage elements, like newspaper. They wanted to show several different views of one thing in a picture — the front, the back, inside, and outside all at the same time.

A Cubist Approach to Drawing

You will need:

Paper

Paints, colored pencils, or markers

First, gather ordinary objects from your home or, like Rivera, include things that have a special meaning to you. Make the composition interesting by selecting objects with distinct colors, patterns, shapes, and textures. Arrange the objects on a table in a way that pleases you.

Next, draw what you see in your still life arrangement. Focus on basic shapes — spheres, cubes, and cylinders—and textures.

Then, draw your still life from a different viewpoint. Draw some objects while standing up, draw a few from another side, and draw some by looking up at them from below.

Reflect: What are the challenges of drawing three-dimensional objects on a flat piece of paper?

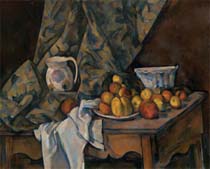

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Apples and Peaches, c. 1905, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer

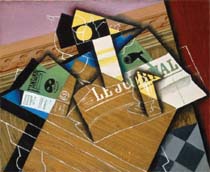

Juan Gris, Fantômas, 1915, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Fund

Pablo Picasso, Still Life, 1918, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection © 2012 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Georges Braque, Still Life: Le Jour, 1929, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection

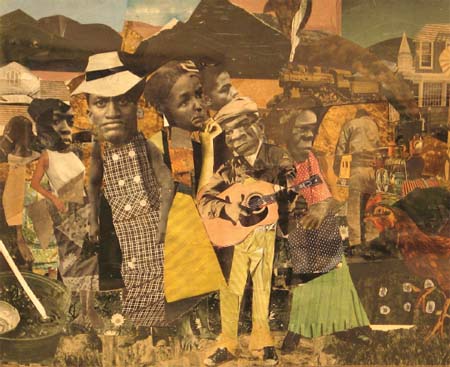

Born in Mecklenburg County in North Carolina, Romare Bearden (1911 – 1988) was just three years old when his family moved from the rural South to a vibrant section of New York City called Harlem, a growing center of African American life and culture. There, Bearden grew up amid the city’s diverse people, the new sounds of jazz, and a wide variety of art, including paintings by Pablo Picasso and sculpture from Africa. When he decided to become an artist, Bearden had the knowledge and experiences of Harlem from which to create his art. He also drew from his memories of his return trips to North Carolina to visit his grandparents and of the summers he spent working in steel mills in Pittsburgh when he was a teenager.

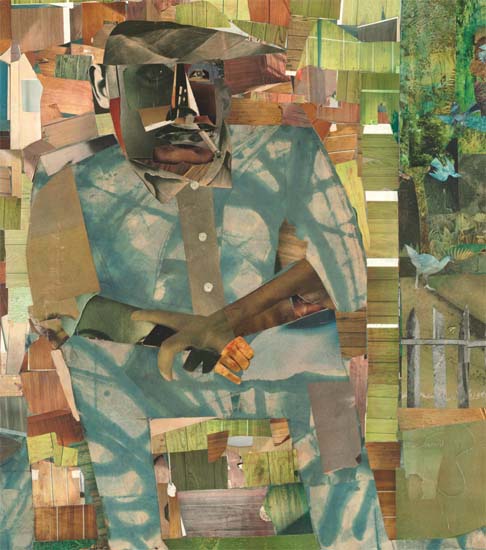

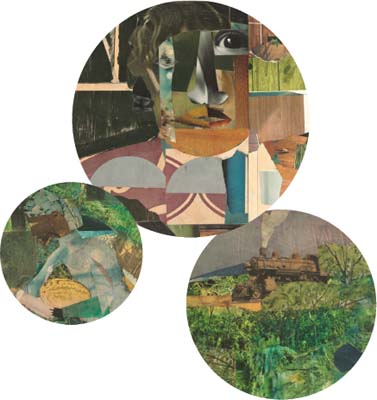

Romare Bearden, Tomorrow I May Be Far Away, 1967, collage of various papers with charcoal and graphite on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Paul Mellon Fund © Romare Bearden Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Romare Bearden in his New York City studio with his beloved cat Gypo (detail), 1974, Estate of Romare Bearden, courtesy of the Romare Bearden Foundation, New York (photo: Nancy Crampton)

Tomorrow I May Be Far Away melds Bearden’s memories of the people, landscape, and daily activities of Southern communities. In the center, a man is seated in front of a cabin. A woman peers through the cabin window, her hand resting on the sill. Behind them is a lush landscape filled with birds, a woman harvesting a melon, and another cabin.

Imagine: What are the man and woman watching? What might happen next? Create a story to go along with this scene.

“My purpose is to paint the life of my people as I know it.” Romare Bearden

To make this image, Bearden began by collecting patterned papers, including magazine illustrations, wallpaper, and hand-painted papers. He cut them into shapes and glued them onto a large piece of canvas, layering the pieces to make the picture. Bearden described his technique as “collage painting” because he often painted on top of the collaged papers.

Look closely

Can you find paper that was cut and repeated throughout the collage? Bearden used the same hand-painted blue paper for the woman’s dress, the man’s clothing, and the water barrel at his feet.

How were the faces made? Bearden arranged as many as fifteen different magazine cuttings for the man’s face, hands, and eyes. He was particularly interested in hands and eyes because they help express a person’s character and thoughts.

Do you see the train rolling across the horizon? Trains appear in many of Bearden’s collages. They reminded the artist of his travels between the North and the South when he was a child. In African American history, trains sometimes symbolize the Underground Railroad, the escape from slavery, and the Great Migration to jobs in the North and West after Emancipation.

“Aah, tomorrow I may be far away

Oh, tomorrow I may be far away

Don’t try to jive me, sweet talk can’t make me stay”

From “Good Chib Blues,” first recorded in 1929

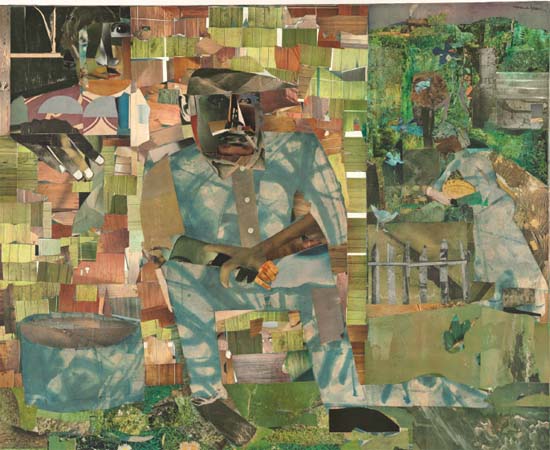

A photomontage is a collage that includes photographs. In Watching the Good Trains Go By, Bearden used photographs to create a rural scene that reminded him of Mecklenburg County in North Carolina. Cutout pictures of trains, faces, and arms, combined with patterned papers, create a busy scene.

Bearden’s art was influenced by his love for jazz and the blues. Music was often the subject of his work, and it also influenced his way of working. One distinguishing feature of jazz is improvisation. In this approach, performers create music in response to their inner feelings and the stimulus of the immediate environment. Bearden advised a younger artist to “become a blues singer — only you sing on the canvas. You improvise—you find the rhythm and catch it good, and structure as you go along — then the song is you.”

“The more I played around with visual notions as if I were improvising like a jazz musician, the more I realized what I wanted to do as a painter, and how I wanted to do it.” Romare Bearden

Create a photomontage

You will need:

Scissors

A glue stick

Cardboard or tag board

Assorted papers, wallpaper sample books, magazines, and/or postcards

Personal photographs

First, think of a place that is special to you. Like Bearden, use your memories of everyday life in that place to inspire your work. What sights and sounds, people, and activities make that place special?

Next, gather photographs and postcards that remind you of that place. Collect patterned papers, such as wrapping paper or wallpaper, and look through magazines for images that remind you of your special place. Cut out patterns and images from your papers, and then arrange and glue them on the cardboard to form the background.

Then, cut out details of people and objects from your photographs. Overlap and layer the pieces to create your scene.

Improvise as you go!

Romare Bearden, Watching the Good Trains Go By, 1964, collage of various papers on cardboard, Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio: Museum Purchase, Derby Fund, from the Philip J. and Suzanne Schiller Collection of American Social Commentary Art 1930 – 1970. Art © Romare Bearden Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Bearden working in his Long Island City Studio (detail), early 1980s, Estate of Romare Bearden, courtesy of the Romare Bearden Foundation (photo: Frank Stewart)

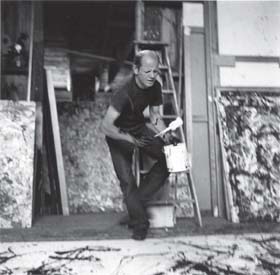

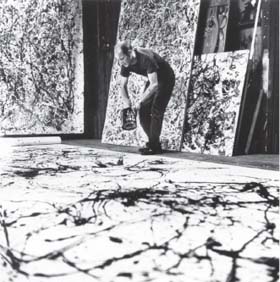

Born in Cody, Wyoming, Jackson Pollock (1912 – 1956) became one of the most original American artists of the twentieth century. He was the youngest of five brothers. His mother encouraged all of her sons to become artists, and three of them did. While he was growing up, Pollock’s family moved around the American West, but when he was eighteen years old, Pollock moved to New York City to become an artist.

Pollock discovered a wide range of styles and art forms that influenced his artistic development: the expressive style of contemporary Mexican muralists, the dream images of surrealists, the lyrical lines of Asian calligraphy, the raw force of works by Pablo Picasso, and the physical process involved in creating Navajo sand paintings. Pollock felt driven to express his emotions through painting.

“My painting does not come from the easel…On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more a part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides and literally be in the painting.” Jackson Pollock

In 1945 Pollock and his wife, artist Lee Krasner, moved to the east end of Long Island. Working in an unheated barn beside his farmhouse, he combined his earlier creative experiments to produce an entirely new way to paint. Dipping sticks or hardened brushes into cans of house paint, Pollock poured, flung, and dripped paint onto large canvases spread on the barn’s floor. (He used commercial house paint because it is thinner and flows more freely than traditional artist’s paints.) Pollock relied on his intuition and his body to infuse his images with emotional force. His process was not all physical, however, for Pollock spent a lot of time thinking about the canvas at his feet before setting his paint in motion. By carefully controlling his movements, he directed gentle spatters, thin arcs, and powerful diagonals of color onto his canvas. The “drip paintings” Pollock made from 1947 to 1951 were unlike any paintings people had seen before that time. They caused a sensation and established a new way of making art — one that made the act of creation visible.

Photographs of Jackson Pollock painting Autumn Rhythm: Number 30, 1950 by Hans Namuth, silver gelatin prints, © Estate of Hans Namuth, courtesy Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, East Hampton, NY

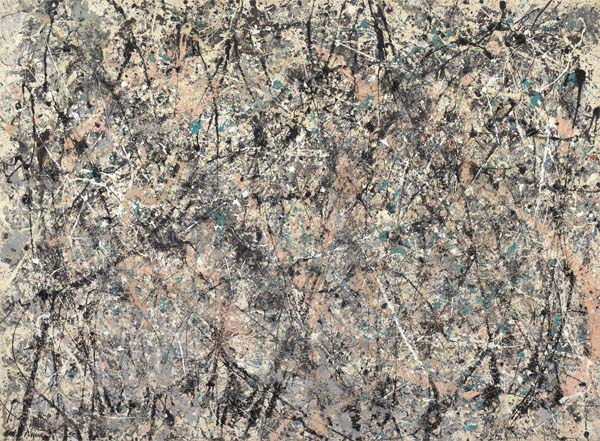

Jackson Pollock, Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist), 1950, oil, enamel, and aluminum on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund

More than seven feet in height and nearly ten feet wide, Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist) is one of Pollock’s most recognized paintings.

Imagine you could step inside this painting

What would it feel like?

Which line or arc would you like to follow? Where would it take you?

How would you move in, around, and under the colors?

Pollock made dense, intricate layers with white, blue, yellow, silver, umber, rosy pink, and black paint. He didn’t use any lavender paint on the canvas, but where the pink and the blue-black colors meet, it looks like lavender. When Pollock’s friend, art critic Clement Greenberg, saw the painting, he said it felt like “lavender mist.” This atmospheric description became the painting’s subtitle.

Pollock’s handprints are visible at the upper left and right edges of the canvas. These are literal traces of the artist’s presence in the work.

Jackson Pollock’s revolutionary art bypassed traditional ways of painting. He invented a method that was uniquely his own. Now it’s your turn to experience the action of making a painting without using a paintbrush. This activity requires special materials and can be a bit messy. Get permission from your parents or other adults first!

You will need:

Newspaper (to cover your work area)

Smock or big, old shirt (to protect your clothes)

Large sheet of white paper or butcher paper

Washable tempera paints

Paper cups or bowls (for the paint)

Look around for materials to paint with:

old mittens

popsicle sticks

cotton swabs

string

straws

sponges

combs

forks

spoons

paper tubes

spatulas

Process

After covering the floor of the work area with layers of newspaper, place a sheet of white paper in the center of the space. Give yourself enough room to walk around all sides of it. You might enjoy listening to music while you work. (Jackson Pollock liked to listen to jazz.)

Work with one color at a time. Dip a pop-sicle stick or another item into one container of paint. Experiment with different methods of painting.

Move your whole body — not just your arm and hand — to reach all areas of the paper. Fill the paper from edge to edge to create an allover pattern.

Experiment with different types of lines: thick, thin, short, long, straight, curved, parallel, diagonal. Vary the height, angle, and speed of your actions.

Think about how to layer your colors. Pause and wait until one color is dry before adding a layer of a different color.

Remember there are no mistakes. Chance occurrences are part of making art!

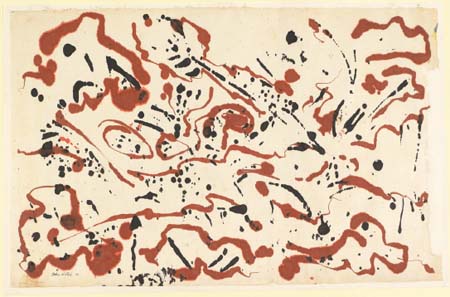

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951, ink on Japanese paper, O’Connor / Thaw 1978, no. 812, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Ruth Cole Kainen

“When I am painting I have a general notion as to what I am about. I can control the flow of the paint…There is no accident, just as there is no beginning and no end.” Jackson Pollock

In the 1950s and 1960s, young British and American artists made popular culture their subject matter. By incorporating logos, brand names, television and cartoon characters, and other consumer products into their work, these artists blurred the boundaries between art and everyday life.

Roy Lichtenstein was one of the originators of this new pop movement. Fascinated by printed mass media, particularly newspaper advertising and cartoon or comic book illustration, Lichtenstein developed a style characterized by bold lines, bright colors, dot patterns, and sometimes words.

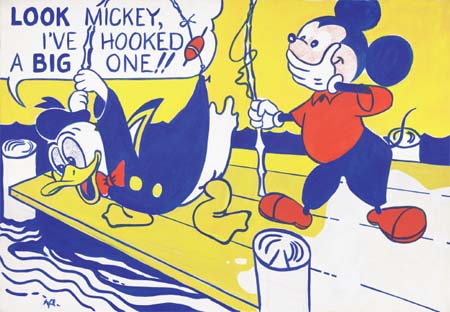

Roy Lichtenstein, Look Mickey, 1961, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Roy and Dorothy Lichtenstein in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art. © Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington

“This was the first time I decided to make a painting really look like commercial art. The approach turned out to be so interesting that eventually it became impossible to do any other kind of painting.” Roy Lichtenstein

Lichtenstein kept this painting, one with personal significance, in his possession until he and his wife gave it to the National Gallery in 1990.

“The art of today is all around us.” Roy Lichtenstein

Born and raised in New York City, Roy Lichtenstein (1923 – 1997) began to draw and paint when he was a teenager. During this time he also developed a passion for jazz and science, and he enjoyed visiting museums. He went to Ohio State University to study fine arts, but his college years were interrupted when he was drafted into the army and sent to Europe during World War II. After returning to Ohio State and completing his studies, Lichtenstein worked as a graphic designer and taught art at several universities. In the 1960s he quickly emerged as a leading practitioner of pop art. This success allowed him to dedicate himself full-time to making art.

Roy Lichtenstein (detail) © Christopher Felver / Corbis

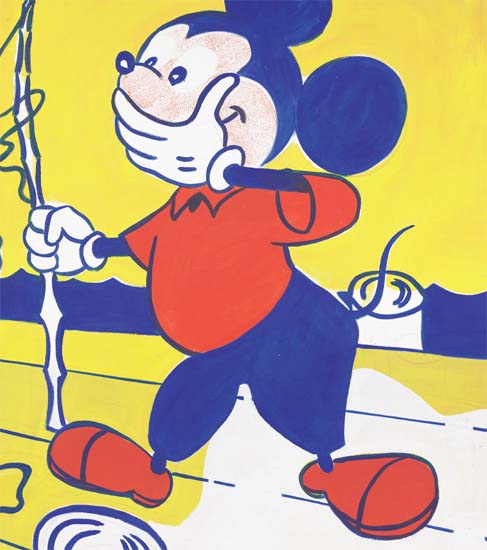

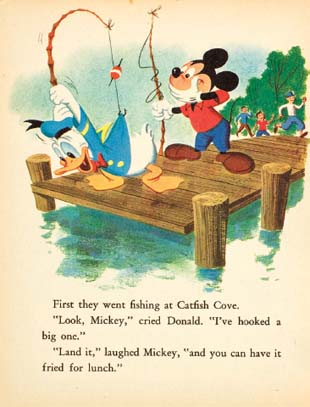

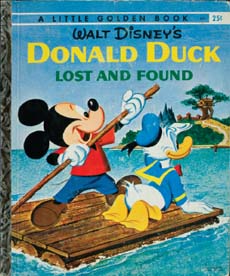

Lichtenstein’s breakthrough came in 1961 when he painted Look Mickey. It is one of his earliest paintings to use the visual language of comic strips. The idea for the painting came from a scene in the 1960 children’s book Donald Duck: Lost and Found, a copy of which probably belonged to the artist’s sons.

Lichtenstein used the design conventions of the comic strip: its speech bubble, flat primary colors, and ink-dot patterns that mimic commercial printing. These Benday dots became Lichtenstein’s trademark. Invented by Benjamin Day in 1879, the dots were used in comic strips and newspapers as an inexpensive way to print shades and color tints. Look at Donald’s eyes and Mickey’s face: Lichtenstein made those dots by dipping a dog-grooming brush into paint and then pressing it on the canvas! He later used stencils to help him paint dots.

Cover and illustration by Bob Grant and Bob Totten from Carl Buettner, Donald Duck: Lost and Found, 1960. © 1960 Disney

“It’s a matter of re-seeing it in your own way.” Roy Lichtenstein

Lichtenstein often enlarged, simplified, and reworked images he found. He never copied the source.

Compare the storybook illustration with Lichtenstein’s painting. What parts are similar? What differences can you find?

Examine the changes the artist made

He simplified the background by removing three people

He rotated the direction of the dock

He added the word bubble, which makes the text a part of the picture

He translated the illustration into an image in primary colors, using red, blue, and yellow on a white background

By making paintings that look like enlarged comic strips, Lichtenstein surprised and shocked many viewers. Why? He made people think about where images come from and how they are made.

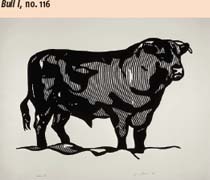

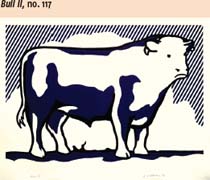

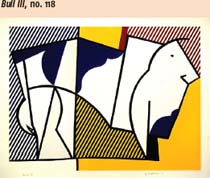

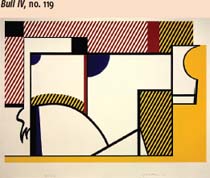

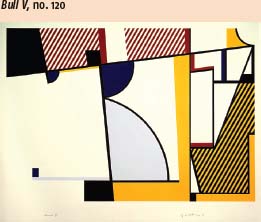

In his Bull series of 1973, Lichtenstein explored the progression of an image from representation to abstraction. Beginning with a recognizable drawing of a bull, Lichtenstein simplified, exaggerated, and rearranged the colors, lines, and /or shapes until the animal was almost unrecognizable. This series reveals the “steps” of the artistic process: the body of the bull is reduced to geometric shapes of triangles and squares, the blue areas refer to the bull’s hide, and curved lines suggest the horns and tail.

Study the images

How are the pictures similar? How are they different?

Which one do you find most intriguing?

Why?

Would you know the last one is a picture of a bull if you didn’t see it in this series?

Create a series of your own

Start with a photograph of a place, person, or object. You can take the photo yourself, or cut one out of a magazine or newspaper.

Then, create a series of two, three, or more drawings. Make each one more abstract by simplifying the shapes, colors, and lines. Reduce them each time until you can no longer recognize your subject.

Roy Lichtenstein, 1973, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Gemini G.E.L. and the Artist