Edgar Degas (1834 – 1917) lived in Paris, the capital and largest city in France, during an exciting period in the nineteenth century. In this vibrant center of art, music, and theater, Degas attended ballet performances as often as he could. At the Paris Opéra, he watched both grand productions on stage and small ballet classes in rehearsal studios. He filled numerous notebooks with sketches to help him remember details. Later, he referred to his sketches to compose paintings and model sculpture he made in his studio. His penetrating observations of ballet are apparent in his numerous variations on the subject.

Edgar Degas, Self-Portrait (Edgar Degas, par lui-même) (detail), probably 1857, etching, National Gallery of Art, Rosen-wald Collection

Degas made more than a thousand drawings, paintings, and sculptures on ballet themes. Most of his works do not show the dancers performing onstage. Instead, they are absorbed in their daily routine of rehearsing, stretching, and resting. Degas admired the ballerinas’ work—how they practiced the same moves over and over again to perfect them—and likened it to his approach as an artist.

Four Dancers depicts a moment backstage, just before the curtain rises and a ballet performance begins. The dancers’ red-orange costumes stand out against the green scenery. Short, quick strokes of yellow and white paint on their arms and tutus catch light and, along with squiggly black lines around the bodices, convey the dancers’ excitement as they await their cues to go onstage.

Here’s a mystery. Did Degas depict four different dancers, or is this four views of one dancer? It could be just one ballerina, pivoting in space, shown in the progression of the motion.

Edgar Degas, Four Dancers, c. 1899, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection

“It is essential to do the same subject over and over again, ten times, a hundred times.” Edgar Degas

Dance students at the Paris Opéra often came from working-class families. It was an exhausting life: members of the ballet corps rehearsed all day and hoped to dance onstage in the evening. Few of them became star ballerinas.

Marie van Goethem, a student who lived near Degas, posed for Little Dancer Aged Fourteen. The daughter of a tailor and a laundress, she had two sisters who also studied ballet and modeled for Degas. Three years after this sculpture was made, Marie was dismissed from the Opéra because of her low attendance at ballet classes. It is not known what happened to her.

Degas’s sculpture also had trouble. Standing almost life-size, it is made of clay and wax. Degas tinted the wax in fleshlike tones and dressed the figure in a ballet costume, with tiny slippers and a wig tied low with a silk ribbon. People were both fascinated and repelled by how lifelike it looked, and they debated whether it was art. Some viewers thought the sculpture was so realistic it belonged in a science museum alongside specimens! After Degas died in 1917, copies of this wax figure were cast in plaster and bronze, and Little Dancer Aged Fourteen grew in fame around the world.

Try to imitate Marie’s pose. The slight sway in her lower back, arms clasped behind her, chin upraised, eyes closed, and legs turned out indicate she is in the casual fourth position, a stance that ballet dancers assume when they are at rest. Instead of depicting the dancer in movement, this sculpture focuses on a psychological state.

“I think with my hands.” Edgar Degas

Edgar Degas, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, 1878 – 1881, yellow wax, hair, ribbon, linen bodice, satin shoes, muslin tutu, wood base, National Gallery of Art, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

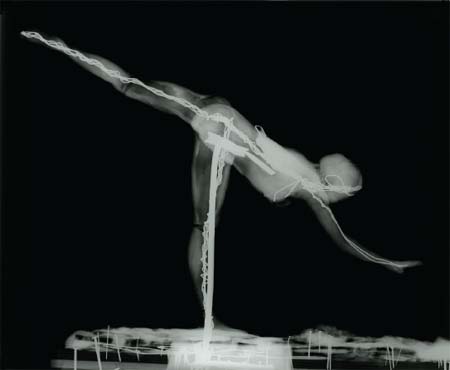

Degas worked on Little Dancer Aged Fourteen for more than two years. X-radiographs of the sculpture reveal what is inside. The artist began with a metal armature, which serves as a sort of skeletal support. He used wood and material padding to make the thighs, waist, and chest thicker. Next, he wrapped wire and rope around the head, chest, and thighs. To create the arms, he used wire to attach two long paintbrushes to the shoulders. Degas modeled the figure first with clay to define the muscles, and then he modeled the final layer of the sculpture in wax.

Degas had satin slippers, a linen bodice, and a muslin tutu made for the figure. A wig of human hair, braided and tied with a ribbon, completed the illusion. A coat of wax, spread smoothly with a spatula over the surface of the sculpture, gives it an overall waxy look.

Degas was a prolific artist, making more than a thousand paintings. He was admired for his drawing skills, particularly his work in pastels, and he was known for his experimentation with printmaking and photography. Degas’s sculpture is a puzzling aspect of his career. His largest figure, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, is the only one he ever publicly exhibited, even though he made hundreds of wax statuettes over four decades. These works, which were discovered in the artist’s studio after his death, were posthumously cast in bronze. The National Gallery owns more than fifty of these wax sculptures.

The smaller wax statuettes, such as those shown here, were part of Degas’s working process. They essentially serve as three-dimensional sketches that probably helped the artist better understand proportion, poses, balance, and movement of form in space.

Try to imitate the pose

An arabesque is a ballet position in which a dancer balances on one leg while extending the other leg back. At the same time, the dancer stretches his or her arms to the side as a way to provide balance. It’s hard to hold this position for a long time! That’s because it is part of a continual movement, and Degas is showing just one “paused” moment in time.

Ballet requires focused control and balance, and Degas had to think carefully about weight and balance when he made sculptures. He began by creating an armature, a framework inside and sometimes outside a work to hold the position. He twisted and bent the wire into the pose he desired. Degas preferred to sculpt with wax that he often combined with a non-drying clay called plastilene. He could easily model and rework the statuettes as much as he wanted, making adjustments to the position. With the armature providing support, Degas was free to experiment with ways to convey the lightness, energy, and motion of a dancer. An active movement, such as the arabesque, makes the space around the sculpture dynamic.

An x-radiograph reveals the metal armature inside the sculpture.

X-radiograph image of Arabesque over the Right Leg, Right Hand near the Ground, Left Arm Outstretched (First Arabesque Penchée), X-ray and photograph, Conservation Laboratory, National Gallery of Art

Edgar Degas, Arabesque over the Right Leg, Right Hand near the Ground, Left Arm Outstretched (First Arabesque Penchée), c. 1885/1890, brown wax, National Gallery of Art, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Edgar Degas, Arabesque over the Right Leg, Left Arm in Front, c. 1885/1890, yellow-brown wax, metal frame, National Gallery of Art, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

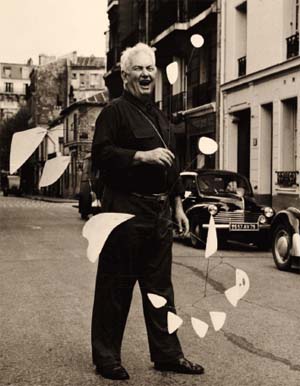

Alexander Calder in his studio, c. 1950 / unidentified photographer. Alexander Calder papers, 1926 – 1967. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Alexander Calder (1898 – 1976) was born into a family of artists in Lawnton, Pennsylvania. Known as Sandy to friends and family, Calder loved to tinker. When he was eight years old, his parents gave him tools and a workspace where he constructed toys and gadgets with bits of wire, cloth, and string. He earned a college degree in mechanical engineering, but unsatisfied with that line of work, he enrolled in art school in New York City and became a newspaper illustrator.

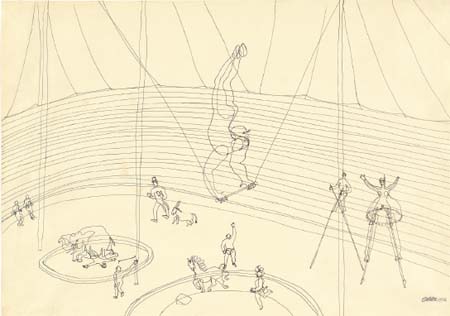

Moving to Paris in 1926 proved to be a pivotal moment in his life. Calder made imaginative, miniature circus animals and performers similar to the toys he invented as a child. He then created a whole circus, complete with balancing acrobats and a roaring lion, and he put on performances for his friends. These circus characters, assembled of wire, cork, cloth, and string, were an early form of moving sculpture. Through the popularity of “Calder’s Circus,” he met other artists living in Paris, including surrealist Joan Miró and Piet Mondrian, whose abstract paintings inspired him: “When I looked at [these] paintings, I felt the urge to make living paintings, shapes in motion.” Calder then created his first motorized abstract sculptures, dubbed “mobiles” by his artist-friend Marcel Duchamp. Developing an ingenious system of weights and counterbalances, Calder eventually invented works that, when suspended, move freely with air currents. The mobiles combine Calder’s sense of play with his interest in space, chance and surprise, movement, toys, and engineering.

Calder returned to the United States in 1933. He set up a studio in Connecticut, where he continued to produce innovative sculptures on both large and small scales. During his lifetime, he received more than 250 commissions from public and private institutions, including the National Gallery of Art.

“When everything goes right, a mobile is a piece of poetry that dances with the joy of life and surprise.” Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder holding his mobile on a Parisian street, 1954 / Agnès Varda. Alexander Calder papers, 1926 – 1967. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Alexander Calder, Untitled, 1976, aluminum and steel, National Gallery of Art, Gift of the Collectors Committee

In 1973, when the East Building of the National Gallery was under construction, Calder was asked to create a giant mobile to hang in the atrium space. After consulting with architect I. M. Pei, Calder made a maquette (a small three-dimensional model) for museum approval. The mobile’s colorful organic shapes complemented Pei’s geometric architecture.

After the design was approved, Calder faced the challenge of how to construct a mobile that was thirty-two times bigger than the size of its model. If it were constructed from steel, as he had originally planned, the finished work would weigh about 6,600 pounds. It would be so heavy that a motor would be required to make it move. Calder collaborated with artist-engineer

Paul Matisse, who used unique aerospace technology to solve the weight and movement problems. Matisse fabricated the mobile’s panels of high-strength honeycombed aluminum with thin skins. Although the panels appear to be solid steel, they are actually hollow and buoyant. In spite of its grand scale, the mobile weighs merely 920 pounds, moves solely on air currents, and maintains a sense of lightness and delicacy.

When asked to title the mobile, Calder replied, “You don’t name a baby until it is born.” The East Building mobile remains untitled because Calder died before it was hoisted up to the frame of the roof. Calder never saw the completion of his last, and one of his largest, mobiles. What would you name it?

Connected to the ceiling at only one point, the mobile has twelve arms and thirteen shaped panels that are clustered into two groups. The upper group, described as “wings,” includes six black panels and one blue panel, all hanging horizontally. In contrast, the lower group consists of six vertical red panels, or “blades.” To make it move on the air currents in the museum, these blades are fastened to the arms at an angle. The speed and direction of the mobile vary when the air hits it, just as the wind moves a boat when it fills a sail.

The mobile has an orbit of just over eighty-five feet. That’s the average length of a blue whale! Calder carefully planned the arms to be different heights so the shapes will never collide. At times, the red blades brush close to the building’s walls, but they playfully avoid contact by a few inches and then continue onward in slow revolution. Always changing, the graceful mobile inspires imagination. What does the mobile remind you of?

“I want to make things that are fun to look at.” Alexander Calder

“It wasn’t the daringness of the performance nor the tricks or the gimmicks: it was the fantastic balance in motion that the performers exhibited.” Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder, The Circus, 1932, pen and black ink on wove paper, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Klaus G. Perls © 2000 Estate of Alexander Calder / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Alexander Calder, Rearing Stallion, c. 1928, wire and painted wood, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Klaus G. Perls © 2000 Estate of Alexander Calder / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“I think best in wire.” Alexander Calder

While a student at the Art Students League in New York City, Calder developed a talent for continuous line drawing, that is, creating an image with one single, unbroken line. He became a skilled draftsman while he worked for several newspapers in the city. Calder took his exploration of line into three dimensions when he began to create sculptures made of wire, a material he had loved since childhood.

Experiment with line in both two and three dimensions

You will need: Paper

A pencil or pen

A single length of lightweight wire, such as plastic-coated electrical wire, copper, or brass wire from a hardware store

Choose a subject you can observe closely, such as a family member or friend, a flower, an object in your home, or an animal. Before you pick up your pencil, let your eyes wander over the edges of your subject.

Next, use your index finger to trace the outlines of the subject in the air, then try tracing them on your paper with your finger.

Finally, take your pencil and begin to draw. Work slowly without lifting the pencil until the figure is finished. Let the continuous line cross over itself and loop from one area to another. Continuous line drawings take practice, so try different ways to make several drawings of the same subject.

Now try it in wire! Think of wire as a single continuous line. Carefully bend and twist a piece of thin wire to create a three-dimensional “drawing” of your subject. To display your sculpture, stick the ends of the wire into a lump of clay or use string to suspend it.

Throughout his life, Calder experimented with materials and learned from them.

Reflect: What was challenging about making a continuous line drawing? What was different about making the sculpture? What did you learn from trying both?

American artist Dan Flavin had a bright idea: to make art with fluorescent lights!

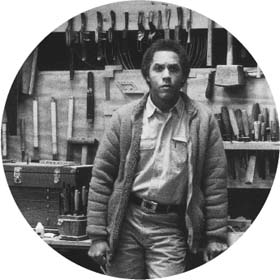

Born and raised in Queens, New York, Dan Flavin (1933 – 1996) doodled and drew his way through school. He became an artist by taking art classes, reading a lot, and getting to know artists while he worked as a guard and elevator operator at museums in New York City. He made his first notes about “electric light art” while employed at the American Museum of Natural History. Flavin was soon constructing the works that would later make him famous.

Dan Flavin, a primary picture, 1964, red, yellow, and blue fluorescent light, Hermes Trust, U.K., Courtesy of Francesco Pellizzi (photo: Billy Jim), Courtesy Dia Art Foundation © Stephen Flavin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

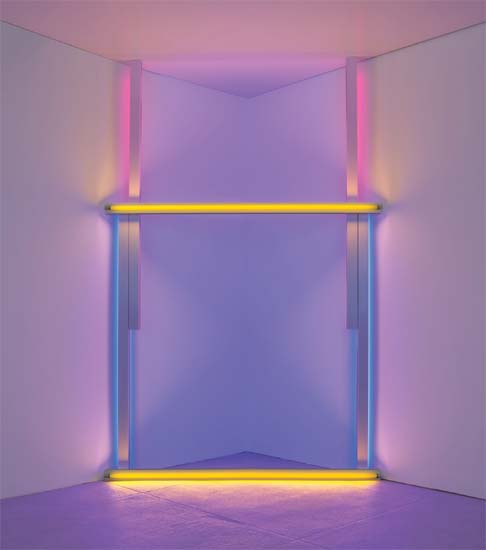

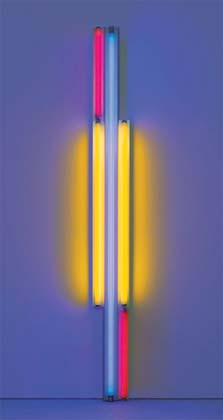

Traditional materials, such as paint, pastels, marble, or bronze, did not interest Flavin. Along with other artists of his generation, Flavin preferred to create art with ready-made materials that he could buy at the hardware store. First, he worked with light bulbs. Next, he experimented with fluorescent lights, and restricted his palette to ten colors: blue, green, pink, red, yellow, ultraviolet, and four kinds of white. The tubes were made in standard straight lengths of two, four, six, and eight feet, plus one circular shape. Flavin managed to make many variations with these limited colors and sizes.

Dan Flavin installing flourescent light, etc. from dan falvin, at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 1969. Photo courtesy of Stephen Flavin © 2013 Stephen Flavin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/ London.

“One might not think of light as a matter of fact, but I do. And it is … as plain and open and direct an art as you will ever find.” Dan Flavin

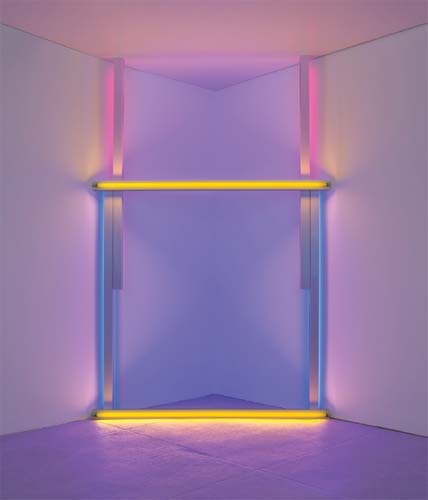

Flavin liked to create his art for unlikely locations — in corners, on the floor, between walls, across rooms, and around windows and doors.

Created for the corner of a room, untitled (to Barnett Newman to commemorate his simple problem, red, yellow, and blue) is made of six fixtures, each eight feet in length, with lamps facing different directions. Two yellow lights turn outward and form intense horizontal lines of color. Vertical blue and red lights are directed away from the viewer, creating a soft glow of color around the lights’ metal pans. The corner of the room seems to disappear due to the reflected light and shadows on the walls, ceiling, and floor.

For Flavin, light was like paint. In his work, the colors of light blend in the air. As a result, the light transforms the surrounding space and architecture. That’s why Flavin called his art “situational.”

Dan Flavin, untitled (to Barnett Newman to commemorate his simple problem, red, yellow, and blue), 1970, red, yellow, and blue fluorescent light, National Gallery of Art, Gift of the Barnett & Annalee Newman Foundation, in honor of Annalee G. Newman, and the Nancy Lee and Perry Bass Fund (photo: Billy Jim), Courtesy Dia Art Foundation © Stephen Flavin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Flavin dedicated this work to his friend and mentor, abstract artist Barnett Newman. He dedicated much of his work to friends, his beloved golden retriever Airily, and earlier artists he admired, such as Henri Matisse, Piet Mondrian, and Vladimir Tatlin.

What happens if a work stops working? The thought of burnt-out bulbs did not bother Flavin. He didn’t consider his work to be permanent. Flavin made diagrams of his light sculptures to serve as certificates of ownership and to document the sizes, types, and colors of his light fixtures. At the National Gallery, the museum staff turns off the lights at night to conserve the bulbs.

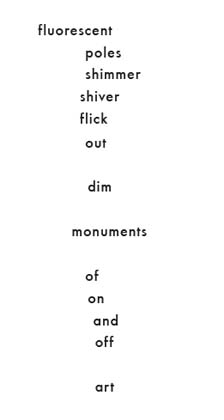

Flavin wrote the poem above in 1961. Does it look like his art? You can almost imagine it as a vibrant pole of light. It’s an example of a concrete poem, one that assumes the shape of its subject. A concrete poem about Halloween might be written in the shape of a pumpkin, or a poem about love could be written in the shape of a heart.

Poem by Dan Flavin, untitled, 10-2-1961

Dan Flavin, untitled (to Piet Mondrian), 1985, red, yellow, and blue fluorescent light, Collection Stephen Flavin (photo: Billy Jim), Courtesy Dia Art Foundation © Stephen Flavin /Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Dan Flavin, “monument” for V. Tatlin, 1969 – 1970, cool white fluorescent light, National Gallery of Art, Gift of the Collectors Committee

Create a poem about a work of art

Start by writing down words that come to mind when you look at the work. They can be descriptive, such as the colors of light and the shapes you see, or they can express your feelings about the art. Include verbs, adverbs, nouns, and adjectives in your list. Use these words to get you started:

Next, organize the words into phrases. Finally, arrange the phrases on a sheet of paper to form the shape of the work of art you selected.

Martin Puryear, Jackpot, 1995, canvas, pine, and hemp rope over rubber, steel mesh, and steel rod, National Gallery of Art, Gift of Edward R. Broida W

Abstract sculptures by Martin Puryear (born 1941) intrigue and surprise viewers with their puzzling shapes and forms. Born in Washington, DC, Puryear regularly visited the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History as a child. These early experiences fostered his fascination with art, organic materials, and nature. The son of a postal worker who was a self-taught woodworker, Puryear began experimenting with wood as a teenager. He studied painting and printmaking in college and art school, but when he returned to the United States after living abroad for four years, he turned his attention to sculpture. Influenced by the many months he spent traveling the world, Puryear incorporates into his art the craft traditions of many cultures, including West African carving, Scandinavian design, boat building, basket weaving, and furniture making.

Ron Bailey, Martin Puryear in his studio, Chicago (detail), 1987

An expert woodworker, Puryear makes his sculptures by hand with natural materials. Many of his sculptures show how they were constructed. Often the organic forms of his sculpture cannot be identified as specific objects, but they do suggest the shapes of animals, plants, or tools. This makes Puryear’s sculptures appear both familiar and mysterious.

Martin Puryear, Lever No. 3, 1989, carved and painted wood, National Gallery of Art, Gift of the Collectors Committee

“The strongest work for me embodies contradiction, which allows for emotional tension and the ability to contain opposed ideas.” Martin Puryear

Lever No. 3 is a large sculpture with a heavy, massive body curving into a long, graceful neck that ends with a delicate circle. Puryear named this sculpture after the lever, a simple machine used to lift or move a heavy object by applying pressure at one point. Instead of looking like a tool, however, the sculpture resembles natural and biological forms. It might remind you of a plant tendril or an animal with a long neck.

Although at first glance it appears to be made of metal or stone, Lever No. 3 is sculpted entirely of wood— Puryear’s favorite material—by using traditional woodworking and boat-building techniques. To make this work of art, he bent thin planks of ponderosa pine into rounded shapes and then joined them together to create an even surface. The base, or body, of the sculpture looks heavy and solid, but it is actually a hollow, thin shell. After assembling the sculpture, Puryear coated it all over with black paint. The dark color hides the seams where the wooden planks are joined, but the artist sanded away the black paint in some areas to show the pattern of the underlying wood grain.

Consider: How might this sculpture look different if it were painted another color? How would it be different if it were made from another material, such as steel or feathers?

Martin Puryear, The Charm of Subsistence, 1989, rattan and gumwood, Saint Louis Art Museum. Funds given by the Shoenberg Foundation, Inc.

“I make these sculptures using methods that have been employed for hundreds of years to construct things that have had a practical use in the world.” Martin Puryear

Martin Puryear, Old Mole, 1985, red cedar, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Purchased with gifts (by exchange) of Samuel S. White III and Vera White and Mr. and Mrs. Charles C. G. Chaplin, and with funds contributed by Marion Boulton Stroud, Mr. and Mrs. Robert Kardon, Gisela and Dennis Alter, and Mrs. H. Gates Lloyd.

Martin Puryear, Thicket, 1990, basswood and cypress, Seattle Art Museum. Gift of Agnes Gund © Martin Puryear

“I value the referential quality of art, the fact that a work can allude to things or states of being without in any way representing them.” Martin Puryear

You will need:

Spools, popsicle sticks, blocks, and scrap pieces of wood

Sandpaper

Wood glue

First, sand any rough edges so the wood is smooth and free of splinters. Then, experiment with arranging the pieces into an interesting composition. Be inspired by the design of something in the world, or create a sculpture from your imagination. When building a sculpture, an artist has to consider height, width, and depth, and how the work looks from many points of view. Weight and balance are important to make the work stable.

Make a sketch of your design or take some notes to remember how all the pieces connect. Then, glue the pieces to each other one at a time, waiting a little bit for the glue to dry.

Lastly, give your work an interesting title.