It must have been apparent to Charcot, from the moment she arrived in the hysteria ward at the Salpêtrière, that Augustine would be his next medical celebrity. She is all symptom, or the idea of the symptom. She is a beautiful object of desire, a victim of misogyny, a Bartleby, a mascot, whatever you would like her to be. There isn’t even historical consensus about what she called herself or what others called her. In nineteenth-century materials, she is never called Augustine; she is either X.L., L., X., Gl., Louise, Louise Gl., Louise Gleiz. or Louise Glaiz., or G. The first mention of “Augustine” I have found is in the second volume of the Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière, a landmark publication of medical photography that sought to present photographs as pure signs of a depicted patient’s illness, clinical features divested of any interiority—it cannot be overemphasized that everything we might find beautiful or interesting in the images, all of the inflections of Augustine’s bodymind, exist despite the manner in which they were captured and recorded. The first edition includes no captions or case histories to describe the photographs, only section titles that categorize the patients as hysterics, epileptics, or “varia”—miscellaneous. After the second volume of the photographs from the Salpêtrière was released in 1878, a reviewer from the British Medical Journal griped, “We must say that we regret the work of such great scientific interest should be to English readers rendered somewhat unsavoury reading by the introduction of long pages of the obscene ravings of delirious hysterical girls, and descriptions of their sexual history . . . if described in the loose words of the patient when delirious and completely under the influence of a hystero-epileptic attack, such description may be interesting to the inquisitive student of disease and human nature, but is actually, in the words of the law-courts, ‘matter unfit for publication.’”

My study of Augustine is often enveloped in the wordless color and texture of a Balanchine ballet or thick brain fog. I wonder if her story and mine are doomed to remain primarily imagistic. The fundamental unease of observing the photographs of the Salpêtrière patients so easily gives way to a bitter delight in an environment where normative, idealized bodies are understood to have gone wrong. Whether or not she was conscious, or had intent, or got to see her images, it is Augustine’s relationship to her own body and her own image that holds my captivation. I am skeptical of the purported cultural value in allowing oneself to be visually documented; when I observe the images taken of me in my modeling years, I see not feminist tools of resistance, but a woman ambushed by economic necessity into an unsavory state of self-corroboration. In those photos, I am cold, bereft, absent; aligned with the aesthetic of the time but also characteristically withholding, austere.

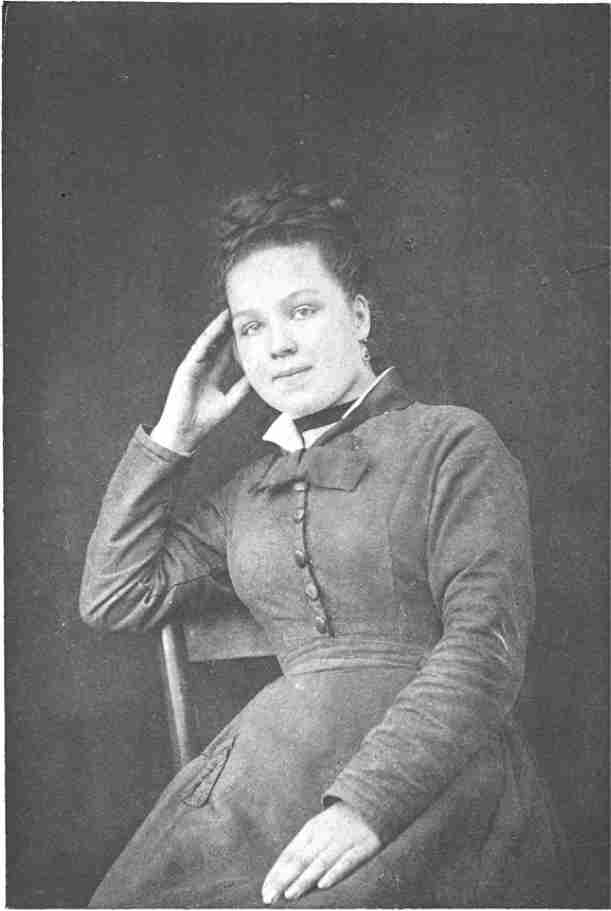

At the Salpêtrière, a hysteric’s symptoms were recognized only when they presented in visual form. In her photographs—I have come to think of them as fundamentally hers—Augustine expresses one big emotion at a time. Joy. Confusion. Pain. Fear. The most neutral is the first photo, taken of her after her arrival, when she was about fourteen. “Normal State” features her sitting calmly, upright, in civilian clothes, comfortably poised in front of the camera, her gaze meeting it directly. Her cheekbones are high, her features symmetrical, and she is unashamed and wearing a slight smile. There is nothing of hysteria in the image. Though eighteen pages of notes follow, covering twenty-one months of her life and many more dramatic gestures, tics, and grimaces—allegedly in correlation with corporeal pathologies—next to nothing can be learned about her life from the volumes documenting her symptoms. Nevertheless, Paul Regnard, who took the medical photographs, knew something about capturing a woman. Augustine is always perfectly lit, well framed, and you can tell she has color in her face, which was something I envied.

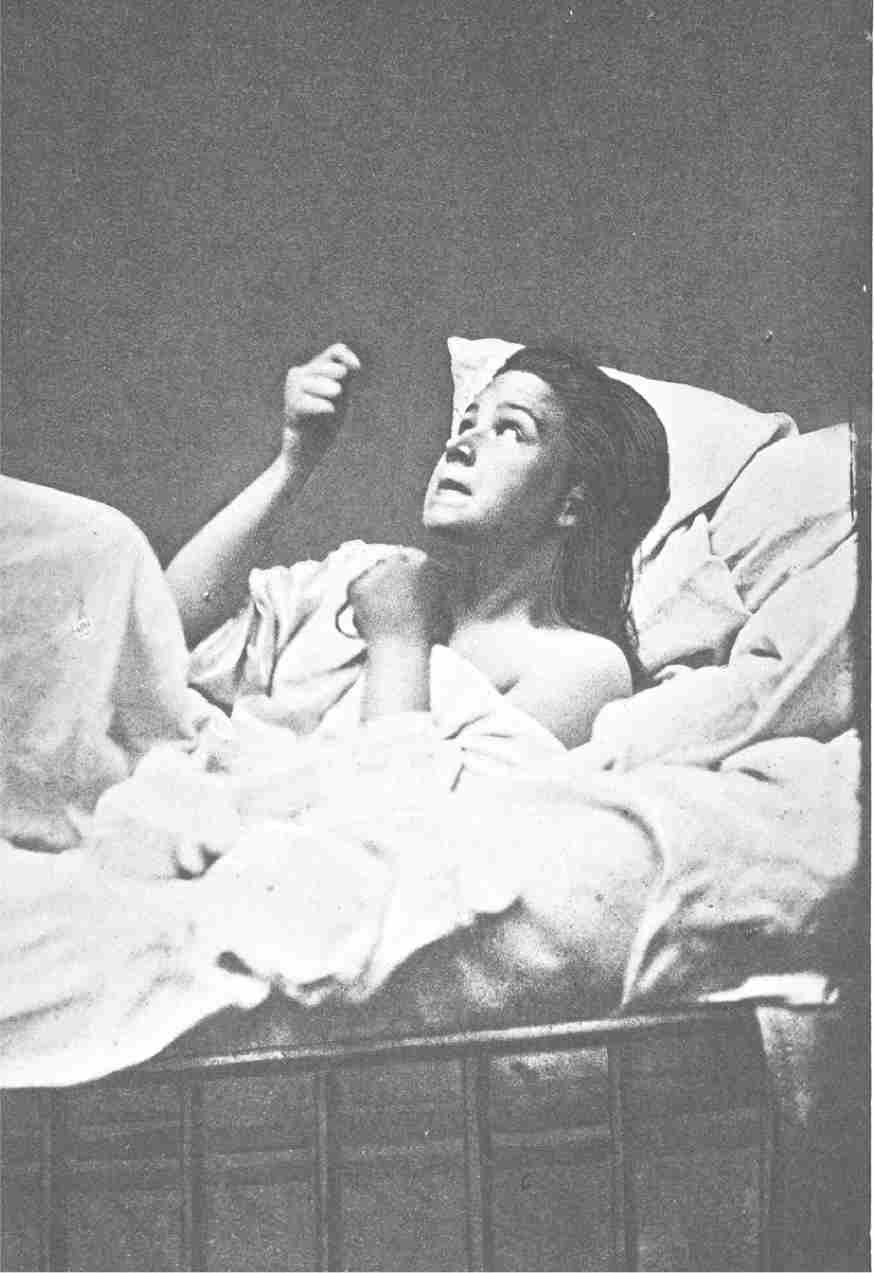

My symptoms eventually kept me from sleeping even when my lifestyle didn’t; everything had fallen apart with several agents, and everything showed in the camera. Augustine is never swallowed up by the light of the camera the way I was and must have practiced holding the passionate poses for a great deal of time. Despite having been subjected to medical tests in which doctors “pulled her hair, tickled, punched, and pricked her; they examined the mucous membranes of her eyelids, nostrils, mouth, tongue, and vulva . . . tested her hearing, vision, taste, and sense of smell,” in the photos, she always appears untouched, distant, possessed only by herself and the singular emotion overtaking her, labeled clearly under each photo. It is never apparent what the depicted medical symptom is, other than a feeling. Augustine was received in the same manner as the pathologized ballet-girl who had preceded her by three decades, and by she who lived 125 years after.

The Salpêtrière women’s costumes differ dramatically to convey something about their state. Fashion historian Yaara Keydar writes, “Before the[ir] attacks, the women are seen fully dressed in tight, tailored dresses, with a tight corset easily recognizable by the silhouette, their waistline emphasized and their hair worn up. In photographs taken during their attacks, however, they are shown wearing white, sheer gowns, stretching in different positions in bed, their hair loose and the curves of their bodies easily discernible.” As writer Maayan Goldman puts it, “Both in the admission reports and in these black and white photographs, we are almost made to believe that the madwoman aesthetic is what’s revealed underneath women’s proper clothes once we ‘peel’ fashion’s skin off.” A woman’s performance—her ability to mimic symptoms while under hypnosis, clad in a sartorial code used to signify her state of health or distress—could be read as a ratification of disease.

Passionate Attitudes: Menace