At Gucci’s spring/summer 2020 show in Milan, the luxury brand stirred up controversy with models wearing straitjackets and institutional uniforms ferried down a conveyor belt in a clinical white room. One model held up her hands in silent protest, the words “Mental Health Is Not Fashion” scrawled in black marker across her palms. The message, however well-meaning, is untrue. Fashion doesn’t really start trends; it condenses and visualizes something already around us. Runway shows rely on metaphor, grasping at the most suitable euphemisms for the anxieties of the time: wearable technology prods at the surveillance state; Balenciaga and Vetements’s references to eastern Europe’s 1990s affinity for American exports expresses neoliberal despair; Viktor and Rolf’s meme gowns (sorry i’m late i didn’t want to come; i’m not shy i just don’t like you) highlight the poisoning of a terminally online generation. Anything can be fashion. As such, clothing has represented concerns about mental health, illness, pain, incarceration, and the medical gaze for longer than runways have existed. There’s the pouf à l’inoculation, a woman’s headdress created in support of inoculation against smallpox in the 1770s. Marie Antoinette’s use of the pouf, which featured symbols of strength, peace, and medicine, helped popularize inoculation. Late eighteenth-century women gestured homage to guillotine victims of the French Revolution by wearing ribbons and chokers around their necks. Victorians romanticized the pale, emaciated figure withering from tuberculosis, which recurred with the “heroin chic” looks of the 1990s. In present-day Japan, the yami-kawaii (sick-cute) look, which emerged from online subcultures, uses sickly pale skin, red puffy eyes, and accessories of fake guns, syringes, gas masks, pills, and bandages to achieve a fragile, ill aesthetic—often considered a response to stigma surrounding mental health or to the psychological duress of the country’s 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown. Gucci’s straitjackets weren’t even very original by contemporary standards. Alexander McQueen’s spring/summer 2001 show featured models walking through a clinical glass box that turned into white padded cells adorned with surveillance mirrors that allowed the audience to watch the models, though the models could not see the audience. Before they made their entrance, McQueen reportedly told the models, “I need you to go mental.” In the Regency period, many people were very concerned with the effects of thin or revealing clothing on their health. Thin muslin dresses left women cold and susceptible to illness, or “muslin disease”—though it is not clear if this term was actually used in the rhetoric of the era. The earliest reference I’ve found, thanks to an admirably unyielding dress historian on Twitter, is in an 1807 Munich journal: “A doctor in Northern Germany warns against a new disease which, in varying forms, threatens the fair sex with death and doom; he calls it the muslin disease.”

According to Gucci, the spring/summer 2020 show’s controversial opening looks were not intended to be sold. They were the “most extreme version of a uniform dictated by society and those who control it.” Creative director Alessandro Michele designed “these blank-styled clothes to represent how, through fashion, power is exercised over life.” To be generous, Gucci’s straitjackets are in conversation with fashion’s long-standing representations of “madness.” The straitjacket obstructs our true—perhaps mad—nature, whereas the subsequent looks in Gucci’s collection purportedly allow our nature to break free. Fashion is positioned as the antidote to restraint, enabling expression through clothes and accessories. None of this, of course, is “political.” This fantasy ethos of the fashion industry is poorly positioned to meaningfully represent the subjectivity of a sick person. And yet the use of “sick” imagery suggests a fixation on illness and pain. A runway show, when best executed and carried to its logical conclusion, acts as a pathography. Even so, fashion is seldom revelatory. Slippery metaphors and vague references reign.

Susan Sontag saw that only a certain kind of pain image makes its way into Western art history: “The sufferings most often deemed worthy of representation are those understood to be the product of wrath, divine or human. (Suffering from natural causes, such as illness or childbirth, is scantily represented in the history of art; that caused by accident, virtually not at all—as if there were no such thing as suffering by inadvertence or misadventure.)”

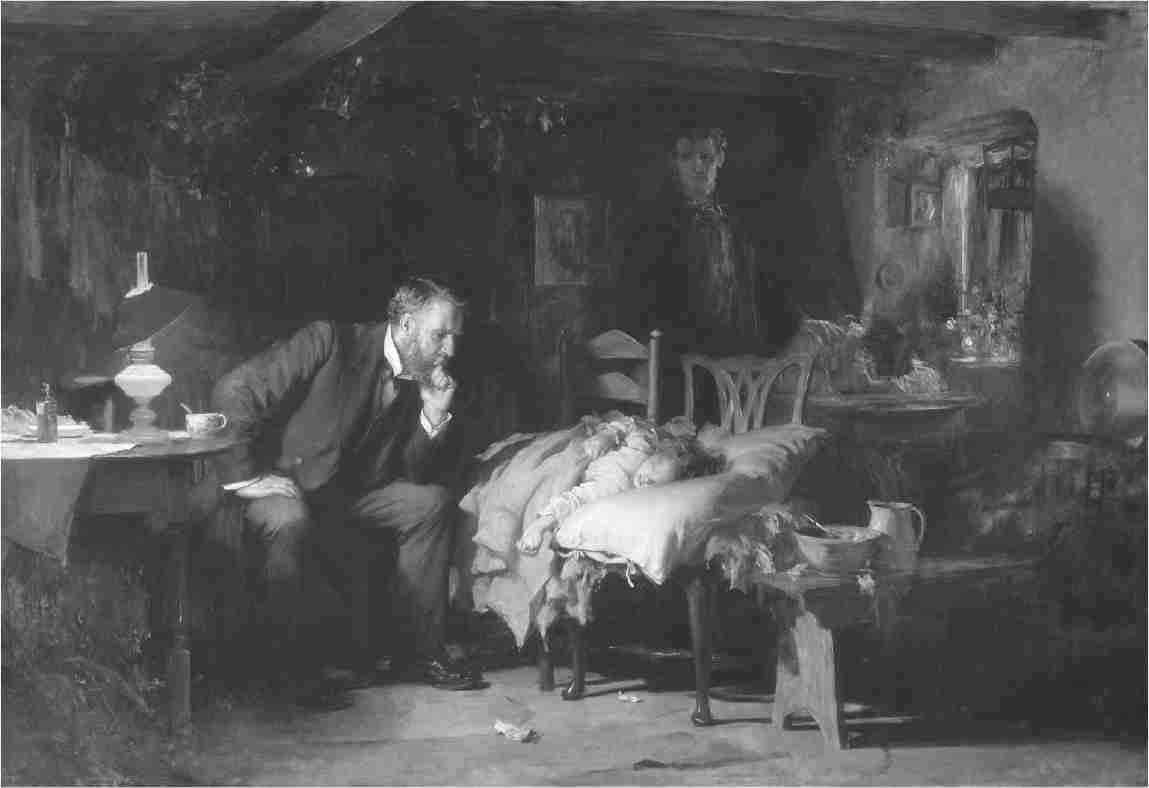

Although tuberculosis was a popular motif in painting, chronic pain and prolonged illness are rare subjects for visual art. When you find them, they are often deathbed scenes and say more about those gathered in the final moments than about the suffering itself. Many such works do not foreground the body of the sick person: Luke Fildes’s 1891 painting, The Doctor, commissioned as a work of social realism, depicts a pensive doctor watching over a child patient, whose face is partially obstructed by a tuft of hair. In 1947, the painting was featured on a US Postal Service stamp for the centenary of the American Medical Association. Two years later, the AMA used the image in its campaign against nationalized medical care as proposed by President Truman: emblazoned across posters and brochures, instructing the reader to “Keep Politics Out of This Picture.” Contrastingly, in Britain, the painting was used as an emblem of celebration for the National Health Service.

The Doctor

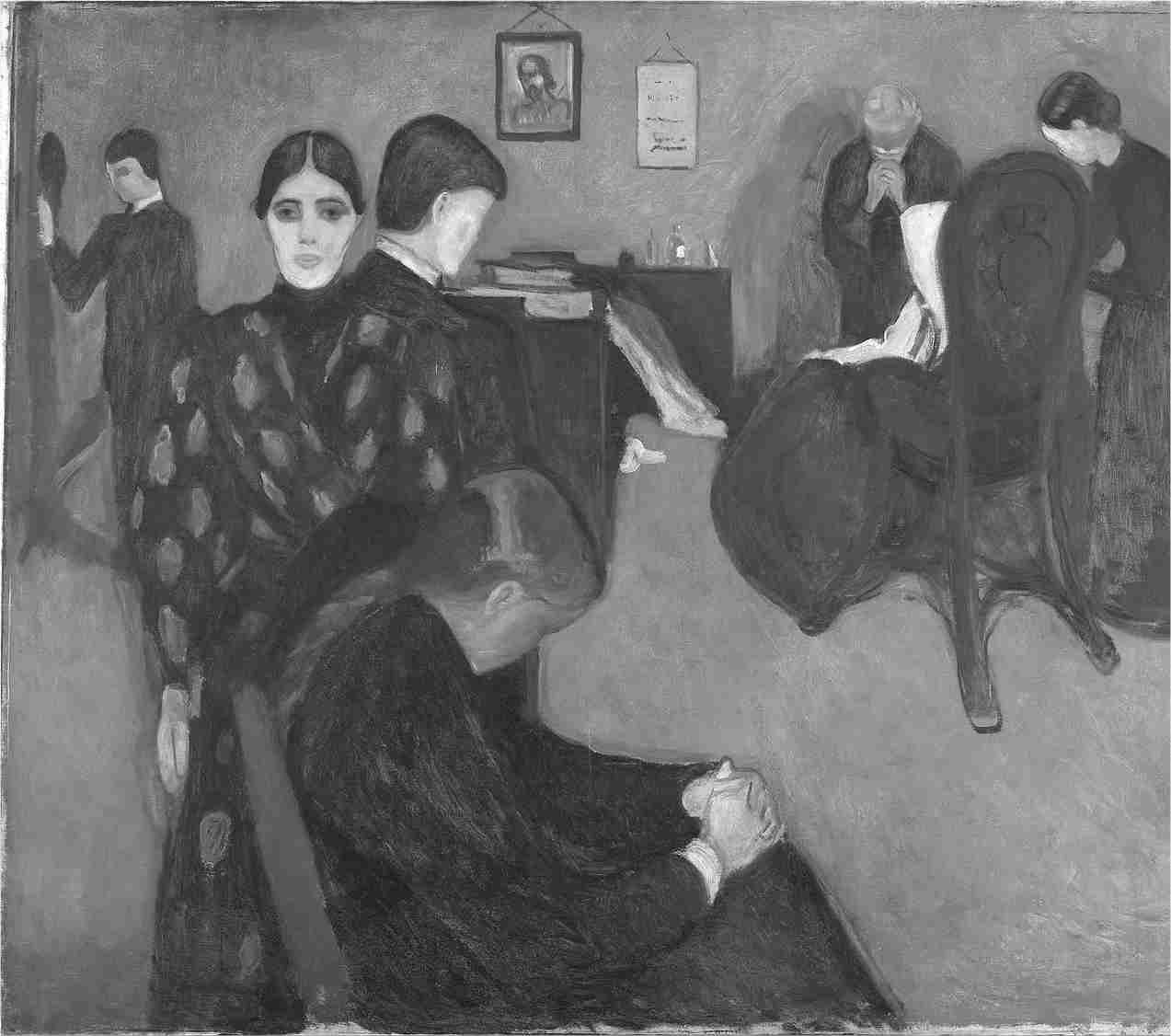

In Edvard Munch’s 1896 work, By the Deathbed (Fever), the face of the sick person is again obstructed. The title subject in the series of six paintings called The Sick Child, based on Munch’s sister, dead of tuberculosis at age fifteen, is blurred, shown in profile, staring past a doting, grieving figure toward a dark, ominous curtain. Though the series is often lauded as “a vivid study of the ravages of a degenerative disease,” it isn’t apparent whether there is anything degenerative about the child’s condition: propped up against a large pillow, she holds the hand of her caretaker, who appears to offer her some small comfort in light of her waning time. In a subsequent painting, Death in the Sickroom, Munch shifts the focus farther from the girl’s physical state: As she sits in a chair facing a corner of the room, she appears partially transparent. The mourners who gather around her retreat into themselves, unsure of how to address or account for the girl, who is withering away before their eyes. The scene doesn’t quite depict empathy, but what it shows is preferable to pity. The sick subject is rarely the subject. I cannot recall seeing a painting from the point of view of the person convalescing in a sickbed or emergency room or trying to write in the midst of pain-induced brain fog.