Since you’re reading this book and aspire to go to business school, it goes without saying that you can read. What needs saying is that the way of reading for which you’ve been rewarded throughout your academic and professional careers is likely not the best way to read on Test Day.

Normally, when you read for school, pleasure, or even work, the main things you try to get from the text are the facts—the story, who did what, what’s true or false. That way of reading may have served you well throughout your life, but on the GMAT you must read strategically.

Because Kaplan knows the test so well, we’ve identified the key structures that will get you points on the test. More importantly, we’ve identified the keywords that signal those structures and tell you what to do with them. Strategic Reading means using structural keywords to zero in on what the test will ask you about. Usually, it’s great to read in order to broaden your horizons. On Test Day, you haven’t got time for anything that doesn’t pay off in right answers.

As you see from the bullet points, keywords help you see the structure of the passage. That, in turn, tells you what part of the text is crucial to the author’s point of view, which is what the test consistently rewards you for noticing.

On the GMAT, questions could give the same facts, but the correct answers could vary depending on the author’s point of view. To see how this works, take a look at the following two facts about Bob:

Bob got a great GMAT score.

He is going to East Main State Business School.

The meaning depends on the keyword that links these facts. Fill in the supported inference for each case:

Bob got a great GMAT score. Therefore, he is going to East Main State Business School.

Supported inference about East Main State: _____________________________________

Bob got a great GMAT score. Nevertheless, he is going to East Main State Business School.

Supported inference about East Main State: _____________________________________

For the first example, you can infer that East Main State must be a good school, or at least Bob must think it is; because he got a good score, that’s where he’s going. Based on the second example, however, you can infer that East Main State must not be the kind of school where people with good scores usually go; it must not be very competitive to get in there. Notice that the facts didn’t change. The keywords “therefore” and “nevertheless” made all the difference to the correct GMAT inference.

This distinction is important because almost all GMAT questions hinge on keywords. Because it cannot reward test takers for outside knowledge, the GMAT cannot ask what you already know about East Main State—but it will ask questions to assess how well you understand what the author says about East Main State.

In Reading Comprehension and Critical Reasoning, keywords highlight the author’s opinion and logic, and they may indicate contrast, illustration, continuation, and sequence. As you continue your GMAT prep, pay close attention to keywords you encounter and what they tell you about the relationship between the information that comes before and after the keywords. Here are the most important categories of keywords and some examples of words that fall into each category.

To see how keywords separate the useful from the useless on the GMAT, take a look at the following Critical Reasoning question—without the answer choices for the moment. You will learn more about analyzing arguments in the Critical Reasoning chapter of this book, but for now, the following questions will guide you through the process of breaking down an argument using keywords:

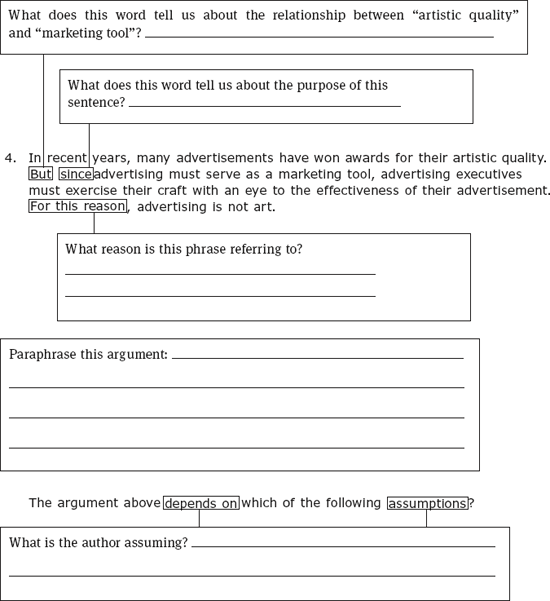

Let’s walk through the above questions in boxes, starting with the question that refers to the word “but.” You may have noted that “but” is a contrast keyword. This tells you that the author believes the terms “artistic quality” and “marketing tool” to be opposed or incompatible.

The next question refers to the word “since,” which falls under the logic category of keywords. Like the word “because,” “since” signals a reason; in terms of an argument, “since” introduces the author’s evidence.

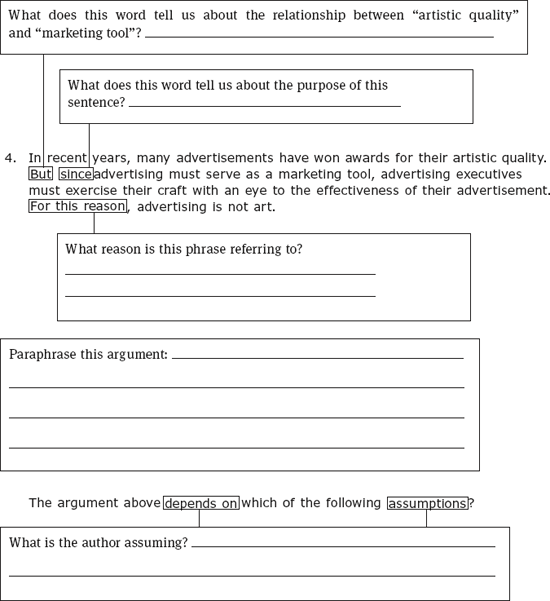

The phrase “for this reason” refers to the evidence that came immediately beforehand—that ad executives must be concerned with effectiveness. “For this reason” also signals that the final sentence contains the argument’s conclusion.

The next box asks you to paraphrase the argument. This means that you should put the evidence and conclusion into your own succinct words: ads aren’t art [conclusion], because they must take effectiveness into account [evidence].

Before looking at the answer choices, you need to predict exactly what you’re looking for: “What is the author assuming?” Look for the gap in your paraphrase above. The author must believe that something judged on its effectiveness cannot be art.

Now take a look at the answer choices and identify which one matches your prediction.

In recent years, many advertisements have won awards for their artistic quality. But since advertising must serve as a marketing tool, advertising executives must exercise their craft with an eye to the effectiveness of their advertisement. For this reason, advertising is not art.

The argument above depends on which of the following assumptions?

Choice (D) matches the prediction and is the correct answer.

By attending to the keywords, you zeroed in on just what’s important to the test maker—with no wasted effort or rereading. Strategic Reading embodies all four GMAT Core Competencies: Critical Thinking, Pattern Recognition, Paraphrasing, and Attention to the Right Detail.