In Western Europe, the period of political instability and the lack of resources, cause and consequence of the fall of the Western Roman Empire were still underway. The Eastern Empire suffered the repercussions of the centuries past while the Arabs and the Muslim peoples enjoyed constantly increased means and contributions. The expansion into southern France followed strategies already adopted elsewhere, raiding, plundering and occupying, or the foundation of coastal centres for penetration inland. For Christianity and its locations, including the territory and activity of the Abbey of San Vittore, these were times of great difficulty and continuous retreat.

However, in the centuries following the year 1000 was seen a new prosperity for the Christian faith, thanks also to religious groups and orders, such as Cathars and Templars, who defended the original principles of the faith and brought to the front once more its purity and authenticity. San Vittore itself, guided by the Spanish monk Isarno, recovered its position, becoming one of the most authoritative and influential institutions in the West. We concern ourselves greatly with this Abbey and the territory directly under its control, as in these locations was found the most ancient documents regarding the Marseilles Tarot . The hypothesis is that the Abbey produced these Icons, today known as Tarot cards, distributing them to their dependencies over this vast area, even to the regions farthest east, as the Duchy of Milan (site of the deck considered the most ancient of all). This supposition is strengthened by the presence of an historical tie between San Vittore, Marseilles, and the Visconti family.

Saint Victor and the Visconti family

Simple Lords of Marseilles and Trets before the year 977, the Visconti were able to create their own sovereignty in French territory without the obligation of rendering fealty to the Counts of Provence. Their tie to Saint Victor, in any case, is certified by the habitual rapport of shared territory, but also by some particular facts. According to tradition, Guillaume de Grimoard (1310-1370) was the 200th Pope of the Catholic Church, from 1362 until his death. He took the name of Urban V and in 1870 was proclaimed Blessed by Pius IX. Already a Benedictine monk at an early age, theologian and Doctor in Canonical Law, he was Abbot of Saint Victor for a number of years. Among his many merits, the future Pope distinguished himself in various diplomatic missions to Italy for the Curia of Avignon, from1352 to1362. In one of these, the Pope Innocent VI sent him to Milan, to the Visconti, to attempt to put an end to the bitter conflict arising from the refusal to acknowledge the temporal sovereignty of the Church.

It seems clear, then, that there existed a direct relationship between Marseilles, Milan, and the Tarot. Equally evident is the consequence: The Icons, exiting the walls of the ancient monasteries, became, over the centuries, a recreational and popular pastime, mere playing cards. What happened? The answer is much simpler than it appears. Precisely because of the changeable happenings of San Vittore and its dependencies, the images underwent a vulgarization. In this way, losing the exclusivity of religious and esoteric environments, they came to be known by a public uneducated in the authentic wisdom of certain Teachings. In those days, the fidelity of a copy of the illustrations, as with text, depended above all on the quality of the original and on the ability of the copier. The decline of this proficiency, caused by chaos which had erupted through the monastery territories, caused a gradual worsening of the features and colours of the illustrations; at the same time, copying, in the hands of individuals who had no knowledge of their true symbolism, degenerated into an inevitable modification of the original. Thus, they who decided to re-design the deck for various purposes, not having at their disposition exact copies of the originals, had progressively (although involuntarily) deviated the authentic ancient Tradition. Over time, the symbols and even more the figures, on the basis of a vastly incomplete graphic (“written”) tradition and on an - inadvertently - erroneous oral transmission, were dispersed and scattered, becoming many different decks. In order to clarify this, we will examine these two cards:

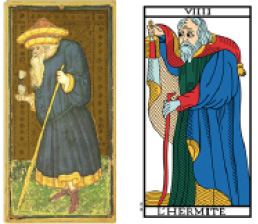

Fig. 4

Visconti-Sforza Tarot, 1400 circa

Fig. 5

Marseilles Tarot of 1760 (Restored)

As you will note, both figures of the Hermit hold an object in the hand: in the first case, an hourglass, in the second, a lantern. We know, from the Codes, the Coded Structure to which we repeatedly refer and which we will explain at length, that the Hermit has within himself the concept of time . Therefore, since in all probability this information was known and orally transmitted, it is understandable that the author of the Visconti image drew an hourglass in the hand of the figure. It is to be supposed that not having the original available, the copier trusted himself to a simple act of memory. In any case, as we will see later, thanks to the system of Codes, the symbol is incorrect because only the lantern confers an accurate and perfectly correspondent meaning to the general esoterical structure, guaranteeing a plurality of sense which is totally lacking in the case of the hourglass.

We may say then that the symbols which are to be found in the diverse ancient decks of the Marseilles Tarot, are witness to this oral form which continued to hand down that which remained of a lost esoteric tradition of the Tarot. This art spread in every direction, in the engravings, paintings and frescoes of the churches, and many artists continued this diffusion without actually realizing its deeper sense. The existence of a model of Tarot containing the secret framework makes it anterior with respect to decks in which this structure is absent or deteriorated, which are to be regarded, precisely owing to this lack, as posterior. Yet the problem of this sort of research is always the same: one begins by studying antique decks different from the Marseilles Tarot, believing them to be the true esoteric source, and judging them to be of a later epoch, does not hypothesize that it is the Marsellaise that contain the original Coded Structure . In the last two to three centuries, from the end of the 1700’s forward, those who have attempted to study the Tarot seriously from a symbolic point of view have been thrown off the track because of this vicious circle. In truth, acting in this manner, we can find nothing for the simple reason that…there is nothing to be found! However, knowing of the presence of the system of reference, it is possible to invert the methodological reasoning . If we estimate the Marseilles Tarot to be antecedent to all others, as if they were the primary source of this Structure , we may use the symbols found in the different ancient decks, as testimony to an oral and a written/graphic tradition which, simply and majestically, confirm the esoteric framework contained in the Marsellaise themselves. Therefore, following the logic of this sort of symbolic “breakdown”, it is easy to guess why the Icons became, over time, a simple game of cards. At the time, in fact, this sort of recreation was so over-used by the entire population, including aristocrats and clergy, that numerous ordinances were passed to forbid its use, at least in religious locations such as inside monastery walls. Often this prohibition had diametrically the opposite effect, causing an increase in the diffusion of this pastime. In any case, among the many references, one is of particular interest for us. This is the most ancient ordinance known today, which expressly forbids the practice of the Paginae (in Latin, page, paper, parchment) and which dates from the year 1337: “ Quod nulla persona audeat nec praesumat ludere ad taxillos nec ad paginas nec ad eyssychum (That no one dare, or take up the game of dice, cards, or chess).”

According to the lexicographer Du Cange and the historian d’Allemange, 24 this may be the most ancient citation in the world referring to card games. In 1408, the word “ card ” and “ playing–card ” are used in the same sentence to describe the same game. What makes this quote so amazingly particular? That of having been unearthed in the statutes of a monastery by now known to the reader, the Abbey of Saint Victor. The most ancient term known today meaning playing-cards, and the history of the Tarot cards, crossed paths in precisely the same place…A probability of this sort is decisively against all statistical calculations, therefore this “coincidence” must be even more heavily underlined. Certainly, it does not prove by itself the origin of the Arcana, but it is an element of comparison for objective deduction deriving from the Coded Structure . In fact, to this same period (the XIV century) dates a petition of the card makers of Lyon, accusing their colleagues of Marseilles of counterfeiting the Lyonese cards; we may affirm that the master card makers of Marseilles, although officially authorized to form a corporation only from 1638, were already active and operative.

To return to the Visconti-Sforza deck, we seem now to be able to collocate it in the correct dimension. Historians maintain that it is the oldest, while esoterists and occultists believe it to be the original, imperfect, model. Both hypotheses are wrong; they are neither the oldest, nor the original model. The card deck known as the Visconti-Sforza Tarot (apart from further historical and archive cataloguing, to which we refer the reade 25 ), is a deck derived from even older Icons, the Marseilles Tarot. We refer to a “faded” copy of a progenitor prototype. Basically, thanks to the contacts between Provence, the Abbey and the Visconti, the images must have arrived by word of mouth or at most, in some altered graphic form, at the court of Milan, leading to the creation of the deck so famous today. However these images may be judged valuable or priceless from an artistic point of view, we can find only a residue of the symbolic Tradition from far earlier; the primitive Tarot, those of Marseilles, bore this Tradition, which is totally absent in these other figures.

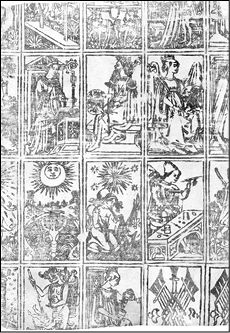

Fig. 6

Cary Sheet, Yale University