“When affirmation and negation came into being, sense (Tao) faded.

After Tao faded, then came one-sided attachments.”

(Chuang Tze [Zhuangzi], IV century B.C.)

Let us return to the example described in the preceding chapter. We supposed that the two houses of the Maison Diev and the Moon appeared in the reply to a question regarding, precisely, a house. We have already mentioned the many questions and the scepticism that these affirmations may create. What would be the mechanism at the base of this sort of event? Even accepting the hypothesis of the presence of the rules of interpretation how is it possible that the cards of the Tarot, which are in any case extracted “casually” after mixing, may truly respond to this query through the direct use of the same keywords used by the consultant in formulating the question? This matter deserves a particular reply and a closer analysis.

During the last century, the psychologist Karl Gustav Jung, researching the theme of the collective unconscious, began to concern himself with a subject particularly interesting to us: meaningful coincidences .What is meant by this term? Today man is used to thinking of events by applying a cause-and-effect principle: if he moves a glass off the table and this, falling to the ground breaks, it seems natural to us that the effect of the breakage is owing to the cause of the movement made. In general, we may affirm that the philosophical principle at the basis of our conception of the laws of nature is, precisely, causality: at least, this is what is hypothesized, often unwittingly and predictably, by a large part of humanity. Furthermore, modern Western thought, whose evaluation of the world is founded mainly on a scientific model, calls for that the research into the solution of any problem to be contingent on the reproducibility of the event in an experimental manner and according to regularity criteria. In practice, in order to ascertain the cause which determines a phenomenon, we analyze the systematicity with which it occurs. We may even overlook the fact that every experiment imposes upon nature, in order to be carried out, a series of restrictions, with the obvious result that, whatever result is obtained will be influenced by a series of conditioning factors. However, the most limiting aspect of this sort of model is that events that occur only once or a few times are not even taken into consideration. In certain descriptive natural disciplines, such as biology and medicine, uniqueness is of the maximum importance: one single verified example of the possibility of this sort is enough to prove existence. The predominant factor in this area is the presence of observers, who are able to convince themselves with their own senses of the existence of a similar entity. On the contrary, in other scientific disciplines, the relevant criteria are different; and unique episodes are considered simple deviations from the statistical norm.

Yet, in contrast to predominant Western thought, there exists a quite different representation of the world. In the East, as is known, there exist various spiritual traditions, which enjoy a wide consensus: Buddhism, Hinduism, Zen philosophy, Taoism and so on. These are the principal examples of that which we might define, on the whole, oriental mysticism. In general, one of the primary characteristics of these traditions is the attempt to maintain a close connection between the theoretical-metaphysical matrix and practical everyday life. In fact, Western man often imagines philosophy or religion as detached from the reality of daily life, as if the two aspects were of difficult or impossible conciliation. Suffice it to reflect upon the general attitude of individuals, in whose behaviour we may glimpse the presence of principles and moral rules but where we perceive the contemporaneous tendency to keep a distance between the various dominions, similar to separate and independent compartments. Eastern man, on the contrary, seeks in daily life a concrete correspondence with abstract and spiritual aspects. Encouraged in this by the spirit itself of the traditions to which he belongs, he sees the world as a test bench for the comprehension of the superior principles pervading it, in which he rediscovers confirmation thanks to the perception of an overall Harmony.

Although Eastern schools differ among themselves on many points, their vision is founded on a common awareness: the existence of a mutual relationship between all events. The essential idea is that the phenomena of the world are manifestations of a fundamental Unity and are to be interpreted as interdependent and inseparable parts of this Whole, representing different expressions of this same ultimate reality. They recognize, therefore, an intrinsic union among themselves, which thanks to this premise, allows the manifestation of Harmony and a superior Order. As an example, let us reflect upon a cardinal concept of Chinese philosophy, that of the Tao . According to Taoism, reality is conceptually knowable because in all things is hidden something which is in some way rational. In the Tao Te Ching , one of the most ancient Chinese texts, is written:

“ The Tao, considered as unchanging, has no name. If a feudal prince or the king could guard and hold it thus, all would spontaneously submit themselves to him. The populace would reach equilibrium without the directions of men. Tao does not act, yet all occur equally everywhere as of its own accord. It is calm, yet able to predispose. The net of the Heavens is so great, so ample, yet it loses nothing. 72 ”

There seems to be in reality a harmonizing principle, a sense that regulates, governs and maintains the world, which Chinese philosophy defines as Tao, Hinduism as Brahman, Buddhism, Dharma, and so on:

“ That which the soul perceives as absolute essence, is the uniqueness of the totality of all things, the great All, which encompasses all. 73 ”

It is easy to see that the Eastern and Western models are rather distant between each other. Yet, perhaps, the differences are not as clear-cut as might be though. Actually, the hypothesis of a significant Unity and of a self-existent sense is to be found as well among ancient Western thinkers. Plato, for example, formulated the existence of images or transcendental models of empirical, tangible things, of which the things themselves were nothing other than reflections, as if there were a sense beyond human consciousness, external to man. At the dawn of Christian theology, Philo of Alexandria, I century BC, wrote:

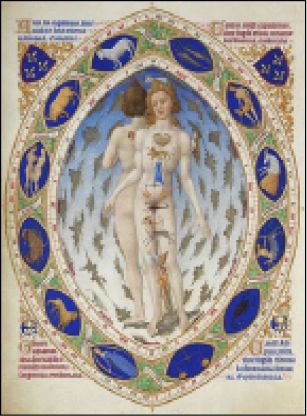

“ God, intending to adapt the beginning and the end of all created things together, as being all necessary and dear to one another, made heaven the beginning, and man the end: the one being the most perfect of incorruptible things, among those things which are perceptible by the external senses; and the other, the best of all earthborn and perishable productions--a short-lived heaven if one were to speak the truth, bearing within himself many star like natures ... For since the corruptible and the incorruptible, are by nature opposite, he has allotted the best thing of each species to the beginning and to the end. Heaven, as I said before, to the beginning, and man to the end. 74 ”

Fig. 1

Anima Mundi

In substance, Philo maintained that the firmament of Heaven is infused into Man who, including in himself the images of his stellar nature, in his quality of a tiny part and intention of the work of creation, includes it all. Therefore, it has always existed, according to a part of antique Western doctrine, reclaimed in later centuries by other traditions such as medieval alchemy, a “ spiritus mundi ”, a “ quinta essentia ” which permeates everything, gives form to all, “fills all, flows in all, unites all and puts all in relation, in order to make of the “ machine of all the world, a whole... 75 ”

In the past, the interconnection of all things, this essential totality in which the human Soul would also participate, was not thought of as extravagant but as something obvious, expected, whereas in modern times, it is generally viewed as an archaism or a superstition to be carefully avoided. Yet perhaps, something is changing. In fact, the belief in the fundamental unity of the universe is no longer an exclusive characteristic of the mystic Eastern experience only of ancient Western thought, because in our times it appears to be one of the most important revelations of modern physics. In penetrating the subatomic world, physicists have observed that the constituents of matter and the basic phenomena in which they take part are all in reciprocal relationship, interdependent: they cannot therefore be interpreted as solitary entities but only as an integrated part of the whole.

“ We are led to a new concept of uninterrupted totality which negates the classical notion of the possibility of analyzing the world in existing parts in a manner separate and independent (...)

We have reversed the usual classical conception according to which the independent “elementary parts” of the world are the fundamental reality and the various systems are merely forms and particular and contingent dispositions of those parts. On the contrary, we must say that the fundamental reality is the inseparable quantistic interconnection f the whole universe and the parts which possess a relatively independent behaviour are only particular and contingent forms within this whole. 76 ”

We may therefore conclude, not without surprise, that quantistic physics, ancient Western pre-Christian philosophy, or Taostic and Eastern thought in general, resemble one another to an extraordinary degree. We glimpse in this a sort of continuity, a golden thread which runs through both humanistic knowledge and scientific, making them even nearer and more similar to each other, To return to the starting point, the cardinal idea of Unity and consequent Harmony is the fundamental ontological element of that which Jung, speaking of meaningful consequences, was the first to call the principle of Synchronicity . What does this mean? Why, in this context, do we speak of meaningful coincidences, of Synchronicity?