Traces and signs of an ancient Tradition tied to the Tarot are not to be found only in paintings but also in edifices dedicated to the Christian cult, as churches. Among these, in particular, we must mention the Duomo of Orvieto, in Umbria, one of the greatest masterpieces of gothic architecture of central Italy. Its construction was begun in 1290 by order f Pope Nicholas IV in order to create a worthy collocation for the Corporal of the Miracle of Bolsena.The façade, an enormous frontispiece reaching towards the sky, is the true face of the monument and is the glowing and scenographic backdrop of this lovely small Umbrian city. Built on the base of a tricuspid design, still conserved today in the Museum of the Works of the Cathedral, it is structured by a rather simple compositive scheme, in which four clustered columns, crowned with spires, originate an equilibrated verticalism of horizontal lines created by the base, the cornices and the trilobate loggia, which divide the whole into two parts. The result is a tripartite wall in which is repeated three times a single geometric motif, that of the portal framed by the columns in the centre from which stands out a great rose window surrounded by a square cornice. According to the most recent historiography, the entire building process may be collocated between the end of the XIII and the second half of the XVI centuries.

Probably contemporaneous to the body of the building, upon which worked a multiplicity of artists in the course of the centuries, it was most likely begun by a Roman artisan, to be continued by Lorenzo Maitani, a sculptor and architect from Siena, in the 1200’s. After his death, the work was carried on more slowly. After the creation of the rose window, between 1354 and 1380, construction continued, of the lateral niches and minor spires (1373-1385) and the superior part of the front, terminated by Michele Sanmicheli and Ippolito Scalza in the second half of the 1500’s. From the end of the 1700’s the church underwent further interventions of restoration, which were finished only in the following century, reaching its definitive aspect, which may be appreciated today. Observing the façade in its entirety (fig. 4), not from an architectural, but a symbolical, point of view, an attentive eye will reveal certain aspects that assume a particular and precise interest for our subject.

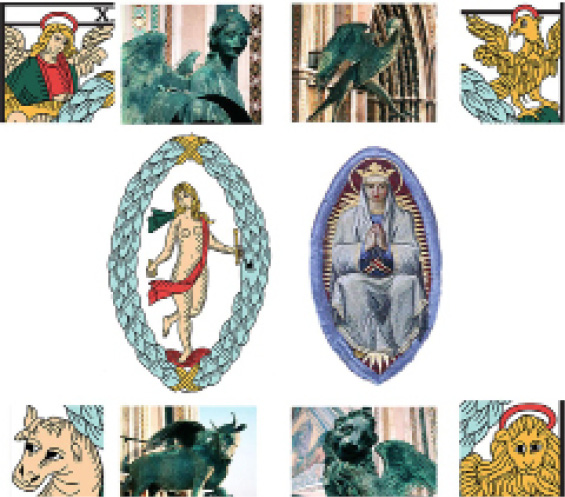

We may immediately note four bronze statues that stand out from the base of the vertical columns of the cathedral: an Angel, a Lion, an Eagle, and a Bull, the four living creatures associated with the four Evangelists present in so many places of Christian worship. First of all, these sculptures, created in the first half of the 1300’s, given the context of their placement, may be considered a clear reference to the tradition of the four Evangelists; the Angel, who represents Matthew, the Lion, identified with Mark, the Eagle with John, and the Bull with Luke. In any case, the same Christian symbolism is in its turn debtor to that even more ancient tradition of the zodiacal constellations of which we have already spoken: the Angel - Aquarius, the Lion and the Bull, which refer to their namesake astrological signs and the Eagle - Scorpio, as found on the XXI card of the Tarot (fig. 5, 6 and 7).

Fig. 4

The Cathedral of Orvieto

Fig. 5

The statues of the 4 Apostles

Fig. 6

The World

Fig. 7

The 4 Apostles in the World card, Compared

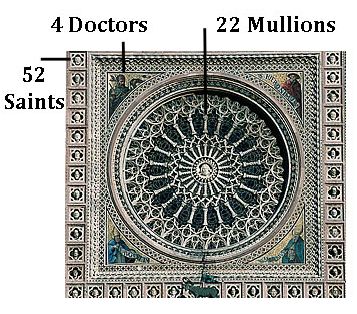

If on the one hand it is evident that the presence of these elements does not prove anything specific by itself, this does not exclude that their existence may serve as a clue or a confirmation for something more precise and quite surprising. For this reason it we should concentrate our attention on another particular of the façade, the great central rose window. It is a work traditionally attributed to Andrea di Cione, called the Orcagna, but was possibly begun by Andrea Pisano around 1347-1348.

An open eye in the heart of the cathedral, the rose window a point of convergence for the entire composition, it is constituted by a frame structure of 22 mullions arranged around the head of the Redeemer, with the rose window situated in two square cornices of which the outer is subdivided into 52 tiles bearing heads of the saints in relief. The corners of the second cornice, between the circle and the first square, are decorated by mosaics portraying four more saints, the so-called “Doctors of the Church”, Saints Augustine, Gregory the Great, Jerome, and Ambrose. Following, is an overall illustration, much clearer than many descriptions:

Fig. 8

The central roundel of the Duomo of Orvieto

The first surprising things of this composition are the two curious numbers derived from its analysis. On one side, we have 22 equal elements, the mullions: on the other, 52+4, or 56 more components, still equal, the saints. May we consider this a coincidence, or is it a direct reference to the number of the Major and Minor Arcana? In our opinion, there is no doubt; the connection is explicit. Even more because it is a confirmation of a true relationship with the Tarot, the 22 represented by the circle, which reconnects to the celestial world, and the 56 by the square, associated with the terrestrial, respecting perfectly the dualism which characterizes the general structure of the Arcana themselves:

22 → Major Arcana → Circle → Celestial

56

→

Minor Arcana

→

Square

→

Terrestrial

If this were not sufficiently astonishing, the central head of the Redeemer with the four later personages, reminds us distinctly of the symbolism of the Christ in the mandorla which we find represented also in the card of the World. This supposition is confirmed, according to a typical mechanism of the Tarot, the Law of Duplicity , by the statues of the four living creatures beneath (the first clue); but also by an oval just beneath the face of Christ, which surrounds the figure of a woman as in the iconography of the XXI card (fig. 4 and 9).

Fig. 9

Comparison of the symbolism

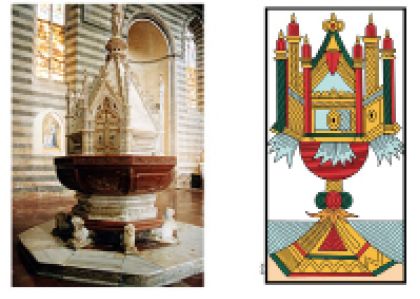

All this is most meaningful, especially considered that, upon entering this church by the main door, another surprise awaits: on the left, in the Chapel of the Corporal, is situated a precious artistic marvel, the baptismal font.

Fig. 10

Baptismal Font and Ace of Cups

It is said that in 1372, a great block of red marble was brought to the church to be used for the font. In 1385, it was transported inside the Duomo and in 1390 was sculpted by Luca di Giovanni di Siena. The work seems to have disappeared and in 1402 Pietro di Giovanni di Friburgo received the commission to create a new font with figures, leaves and flowers, with the left-over red marble. The year after, a Florentine sculptor collocated it in its present position and in 1407, Sano di Matteo da Siena created its octagonal pyramid cover. If we compare the image of the font with that of the first card of the Cup series, the resemblance is undeniable. Is it possible that we are facing another coincidence...? It seems rather that the presence of so many curious “fortuities”, leads to the only possible consideration: that at the base of certain symbolic aspects of this cathedral, so artistically refined and complex, there was the precise intention to codify the message with regard to the Tarot. It is not possible to doubt an undeniable, but predictable, sacred and religious purpose. What might instead perplex, is the evident relationship with the Arcana as, from a temporal point of view we are, let us remember, between the mid 1300’s and its end, about a century before that which is estimated as their period of origin. By consequence then, how may this series of analogies be interpreted? Conforming to the never definitely proved theories of a Renaissance genesis, academics have maintained that the creators of the Tarot, according to them in an epoch certainly posterior to the realization of this work, had copied its symbolism. Therefore, although accepting the connection with the blades, they evaluated the cathedral’s depictions from a religious and esoterical perspective on its own. For this reason, they consider the symbols present in the Arcana as a secondary reproduction and therefore necessarily consecutive, created with an allegorical, didactic and educative function, to satisfy the needs of the mostly illiterate populace. In any case, this conception is still the more benevolent hypothesis, as the extreme and intransigent current of thought of experts has always affirmed that the Tarot was created exclusively for recreational and entertainment use. Beginning from this perspective, research into deeper religious explanations is considered pure fantasy and quackery, magicians’ phenomena; and in any case, as conduct incompatible with the rigor of serious historical and scientific investigation.

Notwithstanding the somewhat uncomplimentary premises, we hold to a different logic: if, as the internal Coded Structure demonstrates, the Tarot originated in a period antecedent to the Italian XV century, its symbolism was not copied later, afterwards, as in the case of the present Christian iconography, but is primordial. Therefore, in a case such as that of the Duomo of Orvieto, we face the exact opposite of what was hypothesized: the façade, as the font, 115 are or contain symbolic elements intentionally and consciously placed to indicate a precise and arcane knowledge related to the Tarot, hidden with the same modalities with which the cards codify their own messages. This interpretation is not at all surprising. The cathedral of the small Umbrian city has a relationship with the secular Tradition of the Tarot. For this reason it is so meaningful that the most ancient Italian citation regarding the card deck, nayb (in Italian naibi , in Spanish naipes and in Flemish knaep ), was found in a chronicle of Viterbo, a city not far from Orvieto, in the year 1379! We may imagine the response of those who will judge this evaluation to be totally without foundation, maintaining that the Duomo was built when the Tarot did not yet exist and that proof from the 1300’s cannot hold up against other documents which indicate the Visconti origin of the Arcana. If this were their reasoning, we feel able to declare that this mode of proceeding is incorrect and reproachable. Our purpose is not to judge the inclination of certain individuals to search out only examples that confirm their own theories, rejecting as untenable those which, however manifestly, contradict them. However we cannot ignore the fact that a similar attitude is tied to the unconscious tendency of the mind to guide and limit one’s research only in certain directions, adopting a point of view which risks emargination of the truth. All this results in an objective distortion of the entire evaluation of the subject under examination, including that mysterious and controversial one, the Tarot.

For this reason it is not acceptable that, in order to elude the clues that might be contradictory, the defence of a supposition (the creation of the Icons during the Renaissance), should be based upon the presence of the hypothesis itself as an evidentiary element. In fact, it is not admissible to declare all data invalidating the birth of the Tarot in the 1500’s unacceptable because it belongs to an epoch in which the Arcana themselves did not yet exist: we risk falling into a paradox, as intolerable as it is absurd! Every trace must be judged for that which it is, a new potential, objective testimony. Loving authentic and sincere research, every clue (and every hypothetical indication) must be considered without preconceptions and in total intellectual liberty. We must free ourselves from every pre-established and fixed supposition, unless we wish to risk pride and personal prestige in concealing a possible new truth. This is the attitude that we hope will be adopted by those who, rich in their multiple experiences with the Tarot, will wish to evaluate serenely the work presented here.