![]()

We had been intrigued by the coincidence Richard Dorment had pointed out of the scandals engulfing the private lives of Edward Burne-Jones and Simeon Solomon at the very time that Bateman abandoned the Dudley Gallery and, like them, never exhibited there again. As time went on, we were to become immersed in the wider life and work of both these artists, but for the moment we concentrated our attention on the period 1873–4.

Solomon’s extraordinary life held us spellbound by the titanic intensity of its triumphs and tragedies. Born the youngest son of a Jewish family of artists, he was precociously talented, entering the Royal Academy Schools at fifteen in 1861. He was taken up by the early members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, especially Rossetti. At first, most of his work was heavily influenced by his Jewish roots, with subjects inspired by texts of the Old Testament to which he brought an intense Hebraic conviction. His technical skill, particularly in the rendering of complex metal surfaces such as chased silver or lustrous fabrics, was superb, especially in conjunction with his daring experimental colour palettes. Burne-Jones was a great admirer of his work from the first, and at one point described him as ‘the greatest genius of us all’ .

As time went on, Solomon’s subjects moved away from his Jewish culture to become more classical in inspiration. A strong strand in many of his paintings was the depiction of people experiencing intense, almost trance-like spiritual states, brought on by the performance of ritualistic religious ceremonies. Another, clearly identifiable, strand was an increasing number of naked or near-naked male subjects which are, to modern eyes, blatantly homoerotic. Since these were criticised at the time for their ‘unmanly’ or ‘unhealthy’ connotations, one can only assume that Solomon set out deliberately to confront the sexual taboos of his time (figs. 35, 36).

By the early 1870s, Solomon’s work was usually simultaneously exquisite and scandalous by the standards of the society about him. In 1871, he brought several of his preoccupations together in a long prose poem entitled A Vision of Love Revealed in Sleep. In view of the fervent intensity of this evocation of spiritual love, there was an element of almost macabre black comedy in his arrest for gross indecency with another man in a public lavatory just off Oxford Street in early 1873. At the same time, there was something truly heroic in his refusal, over the next thirty years, ever to conform to the hypocritical moral conventions of Victorian society. As a result he descended, literally, into the gutter. Shoeless, ragged and an alcoholic, he became an inmate of St Giles’s Workhouse in Seven Dials, London, where he died in 1905.

Fig. 35. Simeon Solomon, Bacchus,1867, watercolour on paper, private collection,

Fig. 36. Carrying the Scrolls of the Law, 1867, watercolour with body colour on paper, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester.

After his crisis, Solomon continued to work mainly on drawings, illustrating aspects of his ‘Vision of Love’ poem. One recurrent figure was the personification of ‘Passion’, who was described as a Medusa-like figure, sunken-cheeked and hollow-eyed with snakes writhing in her hair. These drawings, and the description in the poem, intrigued us. They held out the possibility of an explanation of a strange feature at Biddulph that we had never understood. Inside the porch, on the left-hand wall, were two strange bits of decoration. The first was a lead plaque with a fragment of poetry carved into it:

Hence rebel heart! Nor deem a welcome due

To walls once ruined by a rebel’s hand

Thrice welcome thou if thou indeed be true

To God and to the lady of the land.

Fig. 37. ‘Hence rebel heart!’, Robert’s plaque in the porch at Biddulph.

Fig. 38. The mask in the porch at Biddulph – the ghost of Simeon Solomon?

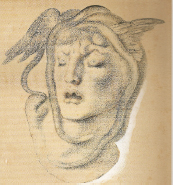

Fig. 39. Simeon Solomon, The Tormented Conscience, 1889, red chalk on paper, 40.6 × 30.5 cm, private collection.

The extended Rs throughout this piece made us attribute the execution, if not the composition, to Robert (fig. 37).

Beneath it, however, was a strange mask carved in red sandstone with hollow cheeks and blank eyes. Two snakes rose through the sketchily represented hair, their heads meeting above the forehead (fig. 38). Solomon had annotated one of his drawings of such a head The Tormented Conscience (fig. 39). Was our sculpture an identification, by Bateman, with Solomon’s image? Or was there even a remote possibility that Solomon himself had been to the Old Hall and attempted a sculptural representation of one of his most haunting images? A possible clue to this might lie in Solomon’s well documented close relationship with a mysterious figure identified only as ‘Willie’, who lived in Warrington, some fifteen miles from Biddulph.

Shortly before his arrest, Solomon and Willie took an extended trip to Italy with Oscar Browning, a sympathetic Eton schoolmaster, and Gerald Balfour. Soon after their arrival, Solomon and his friend deliberately disappeared and went to separate lodgings. Browning took offence, and Solomon wrote to arrange a meeting in order to try to placate him:

I will be at the Braccio Nuovo tomorrow soon after ten with Willie – who has been inexpressibly sweet to me. We shall dine this evening at the Botticella.

On his return, Solomon wrote again to Browning from Warrington, where he was visiting Willie:

The dear Roman, Willie, lives here, or rather, near here. I have had him photographed in divers manners. I think the result very successful but you shall judge for yourself.

Did Solomon continue to meet his friend after the debacle of his arrest in 1873, and if so, did he take advantage of the remote seclusion of Biddulph Old Hall to facilitate this after Robert’s return there in 1874?

One other person, known to be a friend of both Solomon and Bateman, might have provided a motive for him to visit the Old Hall. Solomon had known Edward Hughes since 1869, when he wrote to Oscar Browning telling him that he had taken ‘the beautiful Hughes’ to a choral concert at St James’s Hall:

He was much impressed and looked, leaning on his hand, quite lovely.

Later, Solomon used Hughes and his equally striking seventeen-year-old friend, Johnston Forbes-Robertson, to model for his drawing Then I Knew my Soul Stood by Me and He and I went forth together (fig. 40), which he published as the frontispiece to his prose poem A Vision of Love Revealed in Sleep in 1871. Whatever the truth of their intimacy with Solomon, this very public identification with him appeared to create a serious hiatus in both boys’ lives after his disgrace became public knowledge in late 1873.

In 1874, Forbes-Robertson abandoned his artistic career altogether and became an actor. He quickly joined Henry Irving’s company and travelled to America. In the same year Edward Hughes also stopped exhibiting at the Dudley Gallery and did not show any more work in London until 1880. At the same moment he announced his engagement to Mary Josephine MacDonald, whom he claimed to have been in love with for eight years since she was thirteen years old. In a letter, Mary’s mother said the long delay before their betrothal had been caused by Hughes’s wish to establish himself as an artist, ‘but suddenly it couldn’t be held back’. Despite the apparent new urgency, Hughes failed to marry Mary before her death of consumption four years later in Italy.

Fig. 40. Simeon Solomon, Then I Knew my Soul Stood by Me and He and I went forth together, Hollyer photograph of drawing, 1871.

During this time, he worked as a portrait painter in Liverpool, a place he found deeply alienating. He wrote of it:

I should enjoy myself more if I had more sympathetic people to deal with here . . . I simply hate working away from home (London).

After 1880, although he continued to spend several months each year in Liverpool, Hughes slowly re-established himself in the London galleries. In 1883 he married Emily Eliza Davies in Pimlico, a lady ten years his senior, with Robert Bateman as his principal witness.

During the previous difficult decade, had Biddulph Old Hall provided a secret place where Simeon Solomon could renew his acquaintanceship with ‘the beautiful Hughes’ undetected, when the young man mitigated his lonely life in Liverpool by visiting his good friend Robert Bateman?

Another aspect of Solomon’s story interested us. The persistent trance-like state of his subjects, frequently with poppies entwined in their hair, is strongly suggestive of drug-induced torpor. A Vision of Love was written in 1870 and published the following year. At the same moment, Bateman exhibited Plucking Mandrakes at the Dudley Gallery. While we had taken a close interest in the style, colouring and technique of this painting, especially in relation to the work of the other artists in the Dudley Group, we had never paid much attention to the actual subject.

The rituals surrounding the extraction of the mandrake root from the ground went back to pre-history and were driven by the highly toxic nature of the plant. This danger, in conjunction with the narcotic and hallucinogenic effects of extracts of the bark, had led to the plant’s becoming associated with magic and witchcraft. The soporific and aphrodisiac properties of the extracts meant that the drowsy visions they engendered tended to be vivid and highly erotic. It was thus associated with fertility as far back as the Old Testament, in Genesis 30, verses 16 to 17:

So when Jacob came in from the fields that evening, Leah went out to meet him. ‘You must sleep with me,’ she said. ‘I have hired you with my son’s mandrakes.’ So he slept with her that night. God listened to Leah, and she became pregnant and bore Jacob a fifth son.

In Hebrew, the word for mandrake is dudaim, meaning ‘love plant’.

This renewed interest in the subject of Bateman’s painting had been sparked by a vague recollection of studying Othello in my schooldays and recalling the wonderful phrase, ‘Mandragora, and all the drowsy syrups of the night.’ This phrase seemed to capture the essence of so many of Solomon’s images and of his Vision of Love. We could not help wondering whether it had some relevance to the dreamlike visions portrayed by Burne-Jones, Bateman and other members of their group.

Rossetti and the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, we knew, used laudanum and chloral, both hallucinogenic drugs if consumed in any quantity. Burne-Jones’s lover Mary Zambaco, when she attempted suicide, was described in a letter from Rossetti as ‘wailing like Cassandra, threatening to take laudanum.’ Was there a link here between the visionary paintings, the hallucinogenic drugs, now known to be extremely dangerous and addictive, and the erotic crises that overcame both Solomon and Burne-Jones in the early 1870s? If so, was Women Plucking Mandrakes an indication that Bateman too was involved in this experimentation with narcotics, and did it lead to some form of crisis that forced him, like them, to withdraw from London society and the Dudley Gallery? It seemed plausible – but, unlike them, he was not involved in any publicly acknowledged sexual scandal.

Burne-Jones called the period between 1870 and 1877 his ‘desolate years’, but the truth was that, out of the public eye, he had used the time for intense study. Over these seven years, he refined both his unique vision and the techniques by which he transferred that dream world to canvas. Despite their intensity of feeling and originality, earlier canvases such as Green Summer (fig. 41) or The Merciful Knight had been criticised as technically flawed and poorly finished, in the same spirit as his younger followers had been ridiculed as the ‘Poetry-Without-Grammar School’. He clearly took this criticism to heart. In 1871 he set out on an extended tour of Italy, in which he made a close study of the techniques of the Italian masters, not only of the early figures such as Mantegna, who had influenced him from the outset of his career, but others including Leonardo and Michelangelo. These studies had a dramatic effect upon his output, inspiring him to begin a large number of huge paintings, almost all in oil rather than the heightened water colour he had favoured previously. The new precision and accuracy he brought to these great canvases stunned the art world when they were exhibited for the first time at the opening of the new Grosvenor Gallery in 1877. Overnight Burne-Jones was transformed from a socially ignored, almost forgotten nonentity into the most successful artist of his generation. The roots of this transformation lay in those seven years of isolated concentration, when he had exhibited nothing but had worked obsessively, in private, adding a new discipline and clarity to his extraordinary images (fig. 42).

Fig. 41. Edward Burne-Jones, Green Summer, 1864, gouache on paper 29 × 48.5 cm? private collection.

Fig. 42. Edward Burne-Jones, Wheel of Fortune, 1875–83, oil on canvas, 199 × 100 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Here, surely, was a parallel with Bateman. We had already noted the completely changed style and execution of his work between his last pictures at the Dudley such as Plucking Mandrakes and Reading of Love, both heightened water colours, and the later oils such as Pool of Bethesda, Heloise and Abelard and the portrait of Caroline. Although he was never to achieve anything comparable to the impact of Burne-Jones’s sensational exhibition at the Grosvenor, it seems that Robert used the isolated years at Biddulph to develop his techniques and produce his most important work (fig. 43).

Fig. 43. Detail of The Pool of Bethesda (fig. 18) showing Bateman’s changed technique.

In 1871 the people we had come to associate with Bateman – Solomon, Crane and Burne-Jones – were all in Italy. Since these visits had proved crucial in the development of all these men’s careers, we wondered if Robert had been there with any of them. It was the year of the ten-year census and, intriguingly, Robert was nowhere to be found in Britain. But, try as we might, we could find no evidence anywhere to place him in Italy, either alone or with the others. It seemed the Bateman jinx was still with us.

While we were looking at the 1871 census, we casually tried the next one, for 1881. And, to our amazement, there he was: Robert Bateman, Artist, Biddulph Castle, alone except for a cook and her husband, a stonemason. Suddenly, we had absolute proof that Robert was operating as an artist at Biddulph – not a Victorian country gentleman, but a solitary figure with only a simple couple for company. This was two years before his marriage to Caroline Wilbraham, which apparently transformed his life.