![]()

Nunney was the one place visited by everyone we had met or heard of with a serious interest in Bateman. They had gone there hoping to meet people who would shed light on his life and lost paintings but had all concluded that there was nothing there. Of course this was not entirely true – the churchyard at Whatley, the next village, contains their graves giving the dates of their deaths.

The devotion of their marriage was the most vivid memory of the couple that the inhabitants of Nunney had been able to convey to visitors. Amanda Kavanagh was sufficiently impressed by the frequent repetition of this aspect of their life there to end her article by describing Robert’s love for Caroline as the central motivating force of his life and work. The locals were hardly aware of his painting at all. Richard Dorment had described a conversation with an old man in Nunney who stated categorically that Robert was not a painter but purely a sculptor, whose work he remembered. This at least was nearer the mark than the other local references he was able to tap, all of which centred on mutual devotion, rockery gardens and the founding of bowling clubs. Most of these visits had taken place in the late 1980s or early 1990s, so we felt that the likelihood of even these reminiscences still being available was remote.

One problem was the lack of any consistent information about either the date of, or the reason for, Robert and Caroline’s move from Benthall Hall to this part of Somerset. Kavanagh guessed that the date was ‘probably around 1910’. However, Benthall Hall gave the termination of their lease as ‘about 1906’, raising the possibility that they might have gone elsewhere for a short while. Caroline would have been about seventy at the time so it seemed probable that the move was triggered by a desire to be near to relatives.

Our first instinct was to search for Howards, as their social prominence usually made them easier to find. By now we had a full family tree of the Howard family, particularly Caroline’s immediate relatives and their descendents. We laboriously trawled through census returns of 1891 and 1901 for every household in and around Nunney, but were unable to identify a single relevant Howard in the area who might have prompted them to move there.

The Batemans were no more rewarding. By the early years of the twentieth century both Robert’s parents had died, his father at Worthing and his mother at Brightlingsea in Essex, where his eldest brother John lived and remained till his own death in 1910. His other brother, Rowland, retired from missionary work in India in 1902 and took up a post as vicar of Fawley, a little parish near Henley-on-Thames, before moving north in 1906 to become vicar of Biddulph, his old home parish. His son Melville lived with him until he emigrated to Canada in 1904, while his daughter Mary Sybilla lived in London. Robert’s younger sister Katharine had been widowed in 1895 and for a time acted as housekeeper to Rowland at Fawley Rectory, before remarrying in 1904 and moving to Fareham in Hampshire. She had two married daughters, Mabel Emma Humphries and Sybil Knatchbull, an unmarried daughter, Hope, and a son Henry. There was no trace of any of them living in the Nunney area before Robert and Caroline’s arrival.

Of course, there might have been other reasons for their move. Nunney was a charming little village, clustered round a river with the ruined remains of a medieval castle at its centre. This would certainly have been attractive to Robert, but it did seem a trifle radical, at nearly seventy years of age, to leave a lovely house in which they had lived happily for twenty years in a place with lifelong family links for Caroline to go south to a strange area simply for its picturesque setting. These anomalies had intensified our unease at going there for the sole purpose of making a pilgrimage to their graveside, which would have symbolised the end of our adventure with them. Perhaps this was the reason why several months slipped by before we set out on a blustery January day.

We had almost no information to guide us beyond the name of their house, Nunney Delamere, and the churchyard of St George’s, Whatley, where they were reputed to be buried. We had never seen a photograph or description of either, so we went into the village shop to ask for help. The woman serving was very perplexed. Not only did the name Robert Bateman mean nothing to her, but the house Nunney Delamere was not one she could honestly say she had ever heard of. She proffered a booklet written by the local historical society to mark the millennium, entitled Nunney – The Stone Age. She was flicking through the pages when I stopped her at a sepia photograph of a tall, elegant old man leading a procession, whom I immediately recognised as Robert (fig. 82). The caption read: ‘Robert Bateman leading Nunney’s Empire Day walk, 1912.’ The accompanying paragraph described Robert as of Rockfield House.

‘Now then,’ she said, ‘Rockfield House – that’s a different matter altogether. It’s at the top of the village, up Horn Street.’

Fig. 82. Artistic dandy: Robert leading the Empire Day Parade at Nunney in pale bowler hat and spats, 1912.

Figs. 83, 84. Architectural confusion: Robert’s new entrance front and studio at Nunney Delamere.

When we arrived at the gates of Rockfield House, we could see that the piece of stone with the house name carved on it was newer that the rest of the gate pier. We were to discover later that Rockfield House was a return to its original name at the time it was built. The change to Nunney Delamere had been instigated by Robert and Caroline, perhaps with the slightly pretentious intention of associating it with the ancient De La Mere family of Nunney Castle in the centre of the village. The house was strange and difficult to comprehend. It did not have any clearly discernible pattern or stylistic unity. However, as we walked up the rising drive towards the porch we were struck by a vivid rush of recognition. The rendered surfaces were embellished with brick detailing that corresponded exactly with the brick patterns on the church, dovecote and garden walls at Benthall Hall.

As the principal facade of a substantial classical building, it was not a cogent or successful design (fig. 83). There was an eccentrically placed circular window below the brick cornice and an offset sash window on the ground floor that broke uncomfortably through a mid-course of brick banding, which in turn collided with an ungainly exterior chimney stack, where it terminated. Otherwise the frontage was a blank expanse of render. The flat-roofed porch was to the right, set back, and saved from actual ugliness by a handsome, severely simple stone door surround and metal fanlight which had almost certainly been part of the original house before it was incorporated into the new structure. As with the church at Benthall, the combination of unresolved architectural elements and elaborate, slightly inappropriate detailing betrayed Robert’s hand in the design and his lack of finesse as an architect, compared with his consummate skill as a painter.

We rang the bell and waited anxiously. The door was answered by a small animated woman in her late twenties, who listened to our strange tale with interest but seemed uncertain how to react to our request to see the house. As a tenant, she did not feel she had the authority to show us round, and asked us go across the garden to the cottage attached to the back of the building and ask permission from the owner, Mrs Pomeroy. The view from the garden revealed the true extent of the damage inflicted on this supremely refined, chaste building by the later, gimmicky addition. The harmony of the back facade was achieved through the perfect proportions and precise disposition of its unadorned architectural elements. It was a Regency villa, whose rectangular form was relieved only by a slow curved bay at the centre and shallow, round-headed recesses intended to emphasise the elongated elegance of the ground-floor sash windows (fig. 84). As designers, and lovers of old buildings, we could not help regretting what we regarded as an insensitive addition to the building.

None the less, when we looked carefully at Robert’s extension it immediately gave us two crucial pieces of information. Above the ground-floor sash windows were two highly characteristic brick-lined circular recesses containing inscriptions. The first read ‘R & C B’, and the other the date, 1906 (figs. 85–87). For the first time we could now be certain that Robert and Caroline had not moved in 1910 but well before, in time to have completed and dated their substantial new wing by 1906. Also, since Robert had effectively signed this building there could be little doubt that he had designed not only these alterations but also the church and garden buildings at Benthall which displayed the same highly idiosyncratic brick features.

We made our way past what appeared to be another characteristic Bateman building, a garden pavilion, and on into the rear courtyard, where we knocked on the door of the cottage. No one answered. We could not wait. It was almost 4 o’clock on a late January afternoon and we had not yet been to Whatley churchyard to see the graves, the main purpose of our trip. So we returned to the front door of the main house to ask for Mrs Pomeroy’s telephone number.

Figs. 85–87. The garden front of Robert’s studio at Nunney Delamere showing his and Caroline’s joint initials and the date 1906 in the roundels.

By the time we reached Whatley church, its tower was silhouetted against a dusky sky. The churchyard was about three feet above the level of the lane, with a stone wall surrounding it. Although it was almost dark we could just make out the shape of the most prominent memorials. We had never seen a picture of Robert and Caroline’s graves, but had been told that they were side by side in matching plots. As we began to stumble around the graveyard, our search suddenly seemed to be a desperate undertaking. We had expected the graves to be prominent, commensurate with the Batemans’ social standing, so it was dispiriting to find, when we managed to decipher them in the sallow light of our feeble torch, that the pompous edifices with railings and celtic crosses commemorated Edgar Norris, Mary Adelaide Ashby and Charlotte Saunders Shore.

Eventually, we did catch sight of two identical graves, placed side by side. They were unconventional, with both plots defined by what looked like prominent stone kerbs, with pale, lichen-covered crosses laid flat on the ground within them. We knelt on the kerb and shone the torch on to them but they were encrusted with growth. Brian used a credit card to try to scrape the lichen away. He was struggling to decipher the inscriptions and had just managed to read the words ‘John —, Aged 8 years’ and realised it was neither Robert’s nor Caroline’s grave when our torch gave out and we had to admit defeat. We were left kneeling on the cold ground in the blackness, bereft. We had to find where they were buried, and go there. It was the culmination of our whole journey into their world.

Suddenly, lights flickered across the bare branches above us, and there was the thump, thump of music as a car roared past down the lane. The silence returned. Slowly we fumbled our way back to the car and set off north to Staffordshire in silence.

It was only a matter of days before we made contact with Anne Pomeroy. The striking thing about my conversation with Anne was her response to Robert’s name.

‘Oh yes,’ she said, immediately. ‘I’ve always been intrigued by him. Fascinating man. My younger son is an artist, actually. Of course he’s frightfully snooty about Bateman. He and his friends are all modernists, naturally, but I love his paintings – exquisite in their own way. Peculiarly mesmerising. I find I can look at them for ages and keep finding more in them.’

For a moment my heart stood still.

‘You have seen some Batemans . . .’ I faltered.

‘Oh yes – I have three in my cottage here.’

‘Three authenticated Batemans?’

‘Yes. They’re not originals, of course, I only wish they were. But I wouldn’t be without them now. A man in the village organised to get some beautiful coloured prints for me made from books because he knew I was interested.’

I was astonished by Anne’s casual familiarity with Robert and his work. The relentless pattern of having to explain our interest in this elusive figure was now so deeply ingrained that it was disconcerting to be greeted with such informed enthusiasm. I asked Anne if she had met other people interested in Bateman, and she replied that one or two had contacted her and visited the house over the years.

‘Do come,’ she said. ‘I think you’ll find it’s worth a visit. There are almost no actual things of his, but you get what I would call a “feel” for him here. He’s definitely left something – a presence. Of course my children think I’m gaga, but I do believe that.’

She promised to liaise with her tenant Clare Johnson, who wanted to be there.

Our next visit to Rockfield House, or Nunney Delamere as we still liked to think of it, bore out Anne Pomeroy’s contention that the house retained a distinct aura of Robert and Caroline’s personalities. Clare greeted us in the old kitchen and led the way into the hall and then into Robert’s studio by way of his new entrance lobby extension. It was heartening to discover how much more successful the extensions were inside the house than out. Both the lobby and the studio were handsome, symmetrical spaces, relating comfortably to the bold classicism of the existing interior.

The studio, in particular, was a long, well-paced space with a fine, central fireplace and long sash windows on to the garden. The quality of the window shutters, dado panelling and bookcases was outstanding. It was a big room and when Clare opened the shutters, the sense of its being virtually unaltered since it was built, and strongly redolent of Robert and Caroline, was intensified by the way it was furnished. Clare was a musician who put on recitals, so it was set out with a fine grand piano and a group of gilt chairs with music stands, with rows of chairs for the audience. It was like a tableau of Edwardian cultural life, silently waiting for the double doors to burst open and usher in a glittering throng of white-waistcoated men and begowned women adorned with pearl chokers and elbow-length gloves. One could almost smell the perfume and cigar smoke, and hear the babble of gossip as the performers tuned their cellos and violas. Caroline’s gifts as a singer and pianist were among her most defining characteristics, noted by observers all her life and referenced by Robert when he portrayed Heloise holding a book of music. Only the bare walls betrayed the revolutionary change that had engulfed the world in the century since Robert had conceived this cultivated space as a setting for his art and Caroline’s musicality.

It was easy to envisage how Robert’s compelling canvases would have contributed a disconcerting twist of originality to the soirées that took place here. As they gazed at them, did the Batemans’ more perceptive guests experience a twinge of unease relating these anguished images to the slightly dandified squire whom we had seen leading the 1912 Empire Day parade in white spats and a pale bowler hat? The studio, even without pictures, evoked that man with amazing clarity. Its refinement was derived from classically articulated proportions and fastidious attention to detail. There was no hint here of the agonised, obsessive lover or the distracted visionary which were integral parts of the same personality. In fact, the severe classicism of Rockfield House seemed to emphasise the complexity of Robert’s character which always operated on a surface level of unassertive, polite conventionality masking an internalised, imaginative life teeming with gothic dreams and chaotic, intense feelings that generated the mythical world of his paintings.

Presumably his decision to buy Rockfield House was influenced by the change in artistic fashion against all things Victorian that expressed itself in a widespread return to the appreciation of classical buildings. The lack of conviction in the exterior alterations suggests that Robert could not quite make this transition. Rockfield House did indeed retain a strong presence of both Robert and Caroline but, stripped of his paintings, it was a somewhat two-dimensional, polite account of them. It did not bear witness either to her strength of character, in defying the conventions of her family and social class to marry him, nor to his highly individual creative vision, which sprang from a much more intuitive, concealed place than these rational interiors.

Uncannily, as we left Robert’s studio and were crossing his entrance hall addition, Anne suddenly stopped and did something that perfectly illuminated this contradiction in Robert’s personality. With some difficulty she slid to one side a tall ceramic pot filled with umbrellas and walking canes, to reveal a tiny, exquisitely executed sculpture of an imp or devil, crouching above a baffling cryptic legend incised into the stone skirting of the otherwise austerely classical room (fig. 88). The words

FLIE . SON . TIME FLIES ON

were disturbingly obscure, especially given our uncertainty that the first word even existed as legitimate English. And what could have inspired a childless sixty-four-year-old man to half-conceal this fatherly advice within the fabric of his new building? The initial rush of delight engendered by the skill and audacity of the piece, followed by a nagging perplexity about the exact intention of its creator, was pure Bateman.

Fig. 88. Impish image and cryptic words in Robert’s new hall at Nunney Delamere.

The main hall of the house was a handsome space with a dignified stair, and the area over the studio retained an uncanny sense of having been Robert’s private space. Anne told us that when her family came it had been two interconnecting areas which, she felt sure, were his actual painting and sculpting rooms; the grand studio below, she thought, had been for display and entertaining. The main bedroom was a fine room with its slow-curved bay of sash windows. Clare opened one set of shutters to reveal a room in which it was easy to imagine the aristocratic Caroline being at ease, perhaps quietly reading by a flickering fire, or brushing her hair and preparing for dinner. It was a hushed, private place, where that wise woman could contemplate life about her, and compose herself before re-entering the hubbub of the household below.

The other place that produced an unexpected frisson of excitement was the attic, or old servants’ rooms. At the top of their own staircase, these retained a palpable sense of another world, untouched for many years. Ever since we first set out on our search for Robert’s story, we had always maintained a playful fantasy that, one day, we would find a black trunk in the furthest reaches of a disused garret, hidden beyond backless chairs, rolled-up carpets and piles of china potties. We would wipe a sleeve across the top and reveal the letters RB, with the tail of the R extended. We would persuade the owner to let us break open the trunk. Inside we would find sheaves of exquisite drawings, sketches and bundles of love letters tied in faded ribbon and smelling faintly of eau de cologne.

As we gazed across the servants’ rooms at Rockfield House, the parallels were too strong for us not to ask Anne tentatively whether she had found anything up there when she came to the house – no old trunks, for example? She gave us a sweet, knowing smile that told us she understood and empathised with our dream.

‘Sadly, no. I only wish we had. But there was one thing here when we arrived that we always thought might be his. It’s a sort of bust – the head of an elderly man, made of plaster or something similar.’

It was not, as expected, on a stand in the entrance lobby, because Clare and her husband did not much care for it and had put it out of sight in a cupboard. Anne brought it out for us to see. The moment we saw the sculpture we recognised it as a likeness of Robert in later life (fig. 89). It was animated and craggily modelled in a light material which conveyed a vivid sense of the sitter as a personality. It was by far the most accurate likeness of the older Robert Bateman we had ever come across. When we looked at the base it was signed and dated ‘Conrad Dressler 1889’.

We knew that Dressler was a leading sculptor of the late Victorian era, particularly famous for his busts of the artistic luminaries of the age. When we looked into it later, we discovered that in the same year Dressler had exhibited busts of William Morris, John Ruskin and Algernon Charles Swinburne – further proof that, despite his later obscurity, Robert had at one time held a place beside some of the most influential arbiters of artistic excellence of his day. Anne seemed very pleased, and rather pointedly placed it back on its stand in the hall.

Fig. 89. Conrad Dressler, bust of Robert Bateman, 1889, private collection.

We went through the connecting door into Anne’s cottage, where she donned gardening socks and Wellingtons to show us the garden. She was keen to know how it corresponded to other Bateman garden designs we had seen. We told her that the way the spoil from blasting and digging had been mounded up to create an informal area of rockery, dissected by winding paths, was directly comparable to the surviving parts of the gardens at both Biddulph and Benthall. Anne sent us off to look at the more remote parts without her. By some overgrown laurels we stumbled upon an upright stone, carved on one side with an owl. When we pulled the laurel away from it, we found ‘RB 1906’ carved in a recessed panel along the top (fig. 90).

Figs. 90, 91. Double meaning: two aspects of Robert’s personality carved into a single sculpture, 1906, private collection.

The hollow-eyed sculpture gave a strangely compelling sense of the motionless, staring bird dispassionately assessing the onlooker. We were very excited since, apart from the date-stone on our own house, we had never found a piece of carving actually signed by Robert. However, it was not until we moved the stone to get a photograph that the startling individuality and true quality of the sculpture were revealed. On the back the same blank eyes had been used to animate a fabulous grotesque mask contained within a gothic arch (fig. 91). Although it had been damaged over the century since it was made, this had not destroyed its almost oriental delight in the macabre nor the wilful mischief of the hidden, grinning face. Brian and I laughed when we caught sight of it. It was a moment of instant recognition.

This was the Robert Bateman we had come to know at his most endearing – the subversive spirit that juxtaposed a price tag and a tube of oil paint with the fastidious perfection of a trembling bloom; the artist who insisted we acknowledge the anxiety and absurdity concealed behind everything, even the meditative wisdom of the watching owl. We took photographs, and showed them to Anne when we got back to her. She seemed a little taken aback, as if she had not been fully aware of the carving, and certainly not of the reverse face.

The garden pavilion was a stylish structure built facing the house, with an open front divided by four square white columns . Anne felt sure it was by Bateman, as it was furnished with original oak benches suggesting it had served as a pavilion to Robert’s bowling green nearby. Between the two central columns the floor projected forward, ending in a stone beam with a tiny lead mask of a male head, from which water was designed to flow into a square stone basin (fig. 92).

The moment we saw this, we were reminded of a telephone conversation we had had with Colin Cruise, the biographer and acknowledged expert on the life of Simeon Solomon. He was suspicious that one of the pictures illustrated in his book on Solomon, Love Revealed, was not by him but quite possibly by Bateman. He had felt compelled to include it because the record of Solomon selling it to one of his patrons, George Powell, was authenticated in a letter. However, he felt that Solomon was quite capable of selling a painting by someone else as his own work if he was short of money – which he frequently was. He had not told us which painting it was, but had set us the puzzle of attempting to identify it and letting him know, to see if we agreed with him.

We had picked an illustration of a painting entitled Noon, as we felt that the emphasis on the semi-naked female forms was inconsistent with Solomon, and the organisation of the picture, with foreground figures contained within a strong architectural framework dividing the composition in two, was highly characteristic of Bateman (fig. 93). We also felt the treatment of the group of trees in the background was strikingly similar to that in both The Dead Knight and Women Plucking Mandrakes. Colin Cruise confirmed that we had chosen correctly.

Another aspect of the image characteristic of Robert’s work was the inclusion of statuary and ornamental water as pivotal elements in the overall organisation. The centre of the composition of Noon is focused on a statue of Minerva, from beneath which a tiny grotesque mask spouts water into a square basin. It was uncannily reminiscent of the water feature Robert had integrated into the garden pavilion at his own home in Nunney (fig. 92).

Fig. 92. The highly characteristic square water feature that formed part of the garden pavilion at Nunney Delamere.

Fig. 93. Unsigned painting, Noon, sold to George Powell by Simeon Solomon, now tentatively reattributed to Robert Bateman, private collection.

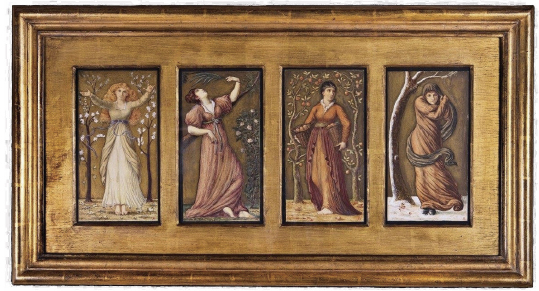

Fig. 94. Robert Bateman, The Four Seasons, watercolour on gold medium, private collection.

The water spout only compounded an exciting development that had already led us to feel that the attribution to Robert of Noon was increasingly credible. We had gone to a dealer’s to see a group of four watercolours depicting the seasons, which were initialled RB (fig. 94). The moment we saw the signature with the square-topped R and extended downward tail, we knew they were Batemans. The delicate modelling of the figures, combined with the exquisitely graded, toning colours set against gilded backgrounds, gave these little pictures an almost jewel- or icon-like intensity. But it was the artist’s response to the female forms discernible through the flowing lines of their animated drapery that instantly reminded us of Noon.

We were enthralled. This time we made no mistake. We bought them and took them home. Against the fractured textures and red sandstone of Biddulph they acquired an almost wanton richness. With so little work of Robert’s having survived, the chance to save them and supply evidence that might allow Colin Cruise to make an informed attribution of another skilful painting to Robert filled us with joy.

Our path back to Anne’s cottage led through another garden feature which was strongly reminiscent, not so much of the gardens at Biddulph or Benthall, but of Cooke’s and the Batemans’ early work at Biddulph Grange. We approached what appeared to be the mouth of a tunnel hewn through an outcrop of rock (fig. 95). The illusion was skilfully maintained through the whole depth of the tunnel, until we opened wooden doors at the end, set in a conventional brick archway, that gave access to a small service courtyard with a range of outbuildings. The whole structure was unmistakably a Bateman confection. It was touching to see Robert still applying the specialised skill with rockwork he had developed in his youth and boyhood, when he worked alongside E. W. Cooke at the Grange and in the Clough walk at Biddulph Old Hall. The same mischievous delight in illusion and whimsical visual tricks was at work here, at the end of Robert’s life, as it had been fifty years before, far away in Staffordshire.

Fig. 95. The playful rockwork arch at Nunney Delamere, typical of Cooke’s and Robert’s work at Biddulph Grange.

Anne Pomeroy had been a delightfully animated kindred spirit all morning, sharing our interest in every surviving remnant of the Batemans’ life at Rockfield House, but by the time we delivered her home she was cold and exhausted. She gamely invited us in but we knew it was time for her to rest, and for us to find the last resting place of Robert and Caroline in the graveyard at Whatley. So we thanked her, made our farewells, and set off.

Try as we might, we had not been able to stop ourselves regarding this visit to the last place with which Robert and Caroline were associated as a private leave-taking. We felt we should bring something, to avoid the emptiness of simply reading the stone and walking away, so were carrying a bunch of Madonna lilies loosely tied with a silk ribbon. We discovered the grave where Robert and Caroline were buried together.

After two long years of searching, in a strange sense we had found them at last (fig. 96). As we anticipated, once we were standing in silence on either side of their burial place, we were unable to do anything but stare at the few bare words on the headstone:

Here lies the body of

ROBERT BATEMAN,

late of Nunney Delamere,

J. P. Salop:

N: August 12th 1842.

Ob: August 11th 1922.

Also of

CAROLINE OCTAVIA HOWARD,

his wife

N: March 20th 1839.

Ob: July 30th 1922.

So few words, and yet how eloquently they conveyed the tragic acceptance that Robert would not be remembered as an artist. The words seemed sad because they were so stilted and inadequate, so unable to convey the truth of the people they sought to commemorate.

Of course, they did not need to do that. The job had already been triumphantly done by Robert, in the language he knew best. His hypnotic paintings were the memorial both to his visionary ability as an artist, and to his lifelong passion for Caroline. Quietly, one by one, they were emerging from the forgotten places where they had been hidden to bear witness to their creator and his beloved.

Our journey home was unexpectedly buoyant and chatty, imbued with a feeling of something achieved and brought to a satisfactory conclusion. We knew that the outstanding task of attempting to track down at least some of the lost paintings had the potential to ensnare us in a labyrinth of false trails and futile disappointments. It was to avoid getting immersed in that frustration that we had not begun it until we had exhausted the search for Robert and Caroline themselves. Now, the daunting moment had arrived for us to set this final quest in motion. We had no clues to follow, so began by acquiring copies of Robert and Caroline’s wills from the Probate Office, to see if any paintings were specifically identified and, if so, who had inherited them. Ninety years after their deaths it seemed a dauntingly vague starting point, but after two years searching for ‘The Lost Pre-Raphaelite’ and his enigmatic bride we were used to that.

Fig. 96. Robert’s and Caroline’s headstone marking their joint grave in Whatley churchyard.