![]()

The next clue arrived within days. Ruth Vilmi’s brother Monty, who lived in America, had found a picture of Henry as a young man. The photograph was taken on a brief visit to England in 1897 when he was twenty-three. He was exceptionally tall and slim, with a comparatively short body and unusually long legs. This physique was highly distinctive and immediately reminded us of an old photograph of Robert Bateman, taken in the Lime Walk at Biddulph Grange (fig. 108). The match with the tall, thin figure was remarkable. The picture of Henry confirmed the description of his good looks and tall figure, identified as defining characteristics all through his life and passed on to his children and grandchildren. However, there was no hint in Henry’s expression of the sad thoughtfulness that united the other pictures we had seen.

The photograph showed a group of five people who apparently made up the amateur cast of A Poetic Proposal, a play performed in the lecture hall at Long Melford, Suffolk, in 1897 (fig. 109). Hill House at Long Melford had been given as Ulick Ralph and Katherine’s permanent address all through their marriage, regardless of where he was working. The photograph indicates that Katherine must have returned there from Dublin, after her husband’s death in 1895. The performers were identified as Mrs Denny Cooke, Mr Sydney Allen, Mr Bennett, Miss Burke (Mabel Emma), and Mr Burke (Henry Ulick). Henry is in the centre of the group and slightly detached from the others. He stands at the back, his stylishly tailored suit and smart cap worn with a panache that makes the others look dowdy. His whole presence exudes a slightly arrogant awareness of a physical magnetism that effortlessly elicits admiration from the world around him. His expression is still boyish, with no hint of the hardness that his face was to betray in the photographs taken at his wedding five years later. It seemed extraordinary to think that a few days earlier, we would have had no understanding of the bizarre background of the cocky lad looking out at us from these photographs.

Fig. 109. Henry with the cast of A Poetic Proposal in Long Melford just before his departure for Peru.

In 1897, Henry had reached one of the high points of his difficult life. He was twenty-three years old and this brief visit to his mother and sisters, two years after his father’s death, must have symbolised his triumph over loneliness, mockery and abandonment. His arrival in Long Melford, fully grown, strong, bronzed, confident and self-reliant, can only have created a sensation. His fantastic tales of life on the far side of the world, of riding for days in the blazing heat, roping cattle and winning rodeos, must have represented a bold assertion that he had risen to the challenge posed to him and proved that there was indeed ‘good in him’. His family could have had no conception of the hunger, drudgery and loneliness that had underpinned his struggle to escape from the freezing back alleys of Toronto. How laughable he must have found their agitation over the forthcoming production in the village lecture hall, after his long fight against starvation in the lawless New World, where everyone carried guns, and used them! How he must have revelled in the adulation of this world of women and their friends as he was paraded from one house to the next.

It must have been on such a visit to his friend Millicent Parry-Okeden that her sister Rose had met and fallen under the spell of the tall, handsome adventurer. Her infatuation offered Henry the chance to complete the process of overcoming the humiliation of his rejection by joining a richer, grander English family than his own. Surely it was under the influence of this adulation that Henry took the perilous decision not to return to the United States, where he had been so successful, but to apply instead to the Peruvian Corporation for a job, and travel to South America later in the year.

For the rejected adolescent, there could scarcely be a decision more freighted with personal symbolism. The Peruvian Corporation was the very organisation that had offered his father, Ulick Ralph Burke, a senior position in 1895. To travel to Peru and make good in that company, the one that had selected his father, held out the opportunity for Henry to demonstrate that he had achieved as much as his father, the brilliant barrister and man of letters. Seen in this context, his courage and will to endure sickness and danger in Peru, though no less awe-inspiring, were tinged with an aura of compulsion which had its roots in his unhappy past.

Once having set himself this challenge of ‘making good’ in Peru, the prospect of returning a failure must have been far more devastating for Henry than anyone else could have realised. How had the Corporation reacted to his prolonged periods of ill-health? Had they waited patiently for him to recover, or had they given his job to someone else? Whatever the reason, by 1900, three years after his arrival, Henry had left the Peruvian Corporation for a speculative oil company. Compared to the solidity of the Peruvian Corporation, with its vast reserves of capital and management structure in London and Dublin, this was a desperate gamble. These were the first oil wells ever drilled in Peru. The aim was to try to tap into the fortunes that were being made by entrepreneurs able to supply the new motor car industry with its lifeblood, petroleum. This previously valueless by-product of refining lamp oil had until then been sold only in tiny quantities, as a stain remover. By 1900, the revolutionary potential of the automobile was understood and production was growing exponentially. Month by month, new manufacturers entered the market across Europe and North America. By 1903, Henry Ford had founded his company and, with the launch of his Model ‘T’ in 1908, the age of motoring for the masses was born. It irreversibly transformed the lives of ordinary people, and created the first of the giant corporations which were to dominate commercial life throughout the new century.

The corresponding demand for petrol at first created a chronic imbalance between supply and demand, which sent the price of oil rocketing. Sites like the tar pits at Talara, where the oil already broke the surface in small quantities, were the obvious places to sink wells. Once sufficient capital was raised to acquire the site and increase its flow through some rudimentary drilling, the company had a free supply of a substance that could be barrelled up and sold at very high prices. For a time it must have seemed as if they had discovered a source of almost limitless riches, without any of the uncertainty, sweated labour and physical danger of the coffee plantations. However, the lack of understanding of the underlying geology of oil exploitation meant that Henry and his companions were completely unprepared when the oil flow slowed to a trickle and finally dried up in 1903. We were building up a vivid picture of a period of personal crisis for Henry. His troubles intensified until they culminated in his return from Peru with his new family in 1904 and the start of an entirely different, settled way of life, as an executive in a large company.

Our interest in trying to find the trail of the lost Bateman pictures had become part of a wider fascination with the apparently unnatural relationship between the Burke parents and their only son. In the Bristol records, there had been one anomaly that we felt could be crucial to our understanding of Henry’s upbringing. Although all the archives indicated that he had accompanied Ralph Ulick on his stay in Cyprus between 1886 and 1889, one account also described him as ‘ending up at Cranleigh College’. If this were true, we felt it might have strongly influenced his development and later life by allowing him to test his father’s assessment of him as ‘a fool’ against the independent opinions of the schoolmasters and other boys. We contacted the college and their archivist looked up the early records for us. Henry did attend the school but only during one single year, 1889, by which time he was sixteen years old and back from Cyprus. The fact that he was not at Cranleigh the next year was no surprise, as we already knew that in 1890 his parents had despatched him to Canada. The disturbing implications of this discovery rekindled our sense that we needed to talk to someone who had actually known Henry.

So it was disappointing when John Beauchamp rang with the sad news that he had developed further health problems. In the meantime, he told us that his daughter Jennifer had studied the Burke family history and suggested we make a date to meet her. When I rang Jennifer she opened our telephone conversation with the now-familiar disclaimer that she knew nothing of Robert Bateman or his paintings. She did mention, however, that she owned one family portrait, of the mother of Henry’s wife, Rose. I asked Jennifer if she had been close to her grandmother Katrina, and was surprised to discover that they had lived next door to each other.

‘I adored her. In a strange way we were companions, after I came to live here. We saw each other practically every day, of course. At first she was next door in the big house, and I was in the cottage, but when she got older she converted the rest of the outbuildings and we lived side by side. We’d often eat together in the evenings, but she ate very little – frankly, she preferred a gin and tonic. Probably how she kept that amazing tall, slim figure that they all had.’

‘Did she talk to you about the past?’

‘Not a lot, but she did. Especially if there were just the two of us. Actually, she had a wonderful way of talking about the old days. Sort of scandalous, or slightly racy. It’s hard to describe but it was exciting, really brought it to life. I loved it!’

‘Did she say much about her father, Henry?’

‘Occasionally – but she was very fond of her mother’s family, the Parry-Okedens. Auntie Vi particularly, and occasionally Auntie Millicent. She had been close to them. Of course, there was a rift with her father after Rose, her mother, died in 1931. She hated Elsie, as she called his second wife – couldn’t stand her. Frankly, I don’t think there was much contact after they got married.’

We arranged to meet at her house in Westwood, near Bradford-on-Avon. In the meantime, we decided to scan whatever records we could find for more information about Henry’s wife Rose, who had effectively shared the bequest of Robert and Caroline’s house in Nunney and lived there surrounded by most of their furniture and personal possessions for nine years until her death in 1931. We wondered what Rose’s relationship had been with the elderly couple who had moved close to both them in Bristol and her relatives at Turnworth House. Presumably she and her children had managed to establish a sufficiently close relationship with Robert and Caroline to influence their decision to identify Henry as the principal beneficiary of their wills.

The more we looked into it, the more it appeared that Rose Burke’s early life had been dominated by the tragic loss of her mother at the time of her birth. Her parents had married in 1871. Her father, Uvedale Edward Parry-Okeden, was a lieutenant in the 10th Hussars and was posted to Lahore a few months after the wedding. Their first child, Millicent, was born in India in 1874. This is the person we had been surprised to encounter in Henry’s will, described as his friend. We had speculated that their friendship might have been forged during childhood in India. However, in 1875, Uvedale and Rose Parry-Okeden had a second child, Elinor Violet, who was born in Walsingham in Norfolk; less than two years after that, the ill-fated birth of Rose, again in Walsingham, was followed immediately by her mother’s death. The children’s father remained based in India until 1879. That year he married Caroline Susan Hambro, and they began a new family, eventually to include seven children.

So the year after Millicent’s birth, her mother had returned to England for good. Henry could not have known Millicent in Lahore unless she, like him, had remained behind in India. This raised the intriguing possibility that the two isolated, motherless infants might have been thrown together and formed an intense bond before both returned with their fathers in 1879. Whatever the truth of this, Rose had been raised by a young stepmother with a constantly increasing family of her own. It would be difficult not to feel an outsider, and be acutely aware of the loss of her real mother, whose names she bore.

By the time we arrived at Jennifer Beauchamp’s house the following Friday, there seemed every chance that, through her close relationship with her grandmother Katrina, she might be able to help us discover the truth about the contorted human relationships that underlay the astounding surface texture of Henry Burke’s life. She lived in an attractive cottage attached to the side of a fine Georgian house, in the centre of the village. She greeted us warmly, but maintained a thoughtful silence as we briefly outlined our discoveries about Robert as an artist. She seemed sceptical about our assertion that the house at Nunney had been inherited by Henry. When we showed her copies of the wills, she became slightly agitated. Despite being a keen researcher into her family’s history, she had clearly had no previous knowledge of this connection. She felt that the association with a figure like Bateman was something she should have been made aware of, either by her father John Beauchamp or her grandmother Katrina. Jennifer remembered one conversation when Katrina had referred to an unnamed ‘fairly famous artist’ who was a distant relation, but she had given no inkling that she had ever seen any of his paintings, let alone that her parents had inherited some of them along with his house. She had talked about the house at Nunney, describing it as grand and comfortable, with three or four staff.

‘To be honest, I got the feeling she was still bitter about her father selling it after her mother died and he “ran off with Elsie” as she put it.’

She picked up Robert’s will from the table.

‘But look at this, 1922. Gran was born in 1904, so she would have been eighteen, grown up, when they moved in after they inherited it. She must have known exactly who Robert Bateman was, and known his paintings – and yet she never said a word to me about it. Even though she must have known how interested I would be, especially when I was doing my research into the family history.’

‘Do you think she had forgotten?’ I asked.

‘I don’t believe that. She could be vague about everyday things that didn’t interest her, but not something like this. She wasn’t shy about letting you know how grand and exotic her friends had been! The romantic artist and his high-born wife would have been right up her street. No, she must have decided not to mention it.’

She searched through a pile of papers and photographs on the kitchen table. There was a photograph of Katrina when she was young – a tall, slender woman in her twenties (fig. 110).

‘Her figure never really altered till the day she died. Fantastic really.’

Another photograph had been described by Katrina as Nunney, though Jennifer was unable to confirm this as she had never been there. It was indeed a photograph of the gardens at Rockfield House. They were almost exactly the same as when we had seen them, except that the rockeries and raised beds were less mature and overgrown. The view showed a tall, elegant, older woman in an ankle-length dress on one of the paths near the comparatively new garden pavilion (fig. 111). Her clothes indicated a date around 1918, and her erect bearing and fine hair, drawn back into a loose knot at the nape of her neck, was strongly characteristic of Caroline. So, too, was the handwriting on the back of the image which read, ‘With very best wishes for Aug 7th and much love.’ It exactly matched the writing on her letter to her cousin, George Howard (fig. 59). For us this was of real interest, as we had never seen a picture of Caroline in later life.

Fig. 110. Katrina in the late 1920s. She clearly inherited her father’s tall and slender figure.

Among the papers was a journal kept by Violet, Rose’s sister, over two years round about 1908. It relentlessly recorded the minutiae of every mundane social call, horse ride, tea party and tennis match that made up the life of a well-to-do spinster of that time. Although we all laughed about this, we could not help wondering how her sister, Rose, who was brought up in exactly the same privileged conditions, had managed to adapt to life with the demonically driven Henry Burke in the savage deserts of Peru. Katrina remembered being told by her mother that the family had been forced to return to England within weeks of her birth in 1904. Jennifer found a note she had made during a conversation with her grandmother that the family’s return home represented a desperate crisis in their life and marriage. They had returned with, literally, nothing – ‘no home, no job, and no money, early in 1904.’ What a moment of desolate disillusionment this must have been for the couple.

Fig. 111. Caroline in old age in the garden at Nunney Delamere.

For Henry, it marked the end of his struggle to make good in the New World, for which he had been prepared to undergo unimaginable mental and physical deprivation. For Rose, it must have represented the culmination of a merciless period of education in the harsh realities of the world around her. From the cosseted luxury of Turnworth House, with her days filled with tennis matches and daydreams of her handsome cowboy, she had been catapulted into the searing heat, disease and primitive poverty of Peru, just as the symptoms of her first pregnancy took hold.

Jennifer was still studying her notes when she suddenly said, ‘Ah, that’s strange. It says here Auntie Vi – that’s Violet, Rose Burke’s sister – hated Millicent, her other sister. That’s what Gran told me. Apparently they never spoke to each other.’

This was fascinating information. Was there the remotest possibility that, after his wife’s death, Uvedale Parry-Okeden had been able to return from India with a child of his by another woman, with no birth certificate, whom he had integrated with his younger daughters and his large second family? If at any point Violet and Rose had suspected such a thing, what an insult she would have represented to the memory of their dead mother, and how utterly estranged from their intense relationship she would have been. How ‘hated’, in a word! Did Henry’s lifelong bond with Millicent have its beginnings in the anonymous world of unwanted children, concealed within the unrecorded margins of British India?

Jennifer was gathering up her papers and photographs when she stopped for a moment at the photograph of a little boy of six or seven, posed with a toy horse on wheels (fig. 112). She gazed at it with a gentle smile.

Fig. 112. Katrina’s younger brother, John, aged six or seven.

‘Gran loved that picture. It always reminds me of her. It was always around somewhere in her day. It’s her little brother – the one who died, John, his name was. It still seemed to affect her when she talked about him, even as an old lady. I think he was only about eight or nine when he died. Gran always said that her mother was heartbroken.’

Jennifer got up from the table and took us over to the fireplace to look at the portrait of Rose’s mother that hung above it (fig. 113). It was titled and dated ‘Rose 1877’ on the face of the painting, but there was no sign of a signature. The romantic quality of the child-like face with pale luminous skin framed against amber-gold trusses of curly hair was compelling and strongly evocative of the age of the Pre-Raphaelites. It was an ethereal, almost spectral piece, far more than a workaday portrait mechanically setting down a likeness. Its infinitely subtle, graded colouring and merging outlines suggested a figure recorded from a dream or memory, the twilight world of the mind, rather than from the stark daylight of physical reality. It was not hard to see why this haunting vision of her lost mother, who had died in the act of giving life to her and whose name she was destined to perpetuate, had become the most cherished possession of Rose Parry-Okeden as she progressed through her life and became Rose Burke, with children of her own.

Its unique quality might have been designed to imprint upon the mind of a bereaved little girl an idealised image of a gentle mother figure, when she felt she was being pushed aside by the arrival of more and more babies to her father and young stepmother. The cult that Rose had developed around this image had clearly communicated itself to her own daughter. Katrina had kept this single painting with her to the end of her life, despite retaining almost nothing else belonging to her parents, and passed it on as a precious inheritance to her granddaughter. Jennifer told us that it had been done from a photograph, which she showed us (fig. 114).

Fig. 113. Robert Bateman, Rose 1877, 1906–8, oil on canvas, private collection. Jennifer Beauchamp’s portrait of Rose Burke’s mother Rose Lee-Warner, attributed to Robert Bateman, is the single painting to have remained in the family.

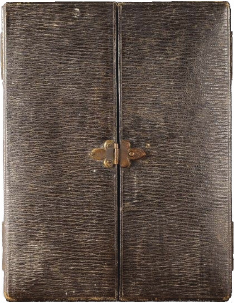

Figs. 114, 115. The case and photograph (with lock of hair) which inspired the painting of Rose some year later.

It was in a wonderful Victorian leather case, and contained a lock of faded blonde hair. Her contention that the painting had been copied from it was clearly correct as the pose was identical. Jennifer went on to outline a longstanding family mystery surrounding the date it had been painted. Apparently this could not have been 1877, as the sitter had died in the first few days of that year, never having recovered from giving birth to Rose (Henry’s wife) in late December 1876. She then described another family tradition, passed on to her by her grandmother, that the portrait was unsigned because it had been painted later by an artistic member of the family. Jennifer had always understood this to be one of the Parry-Okedens – but at that stage she had never heard of Robert Bateman. After he moved to Nunney, what could have been more natural than for Robert to use his skills to develop an oil painting from the treasured photograph of Rose’s lost mother? Surely this was the one gift that had the power to create an insoluble bond between the Batemans and Henry’s wife that would last for the rest of their lives. Jennifer fretted about the risk that the painting might get damaged, and asked if we thought it should be put behind glass. Her pervasive concern for the preservation of this one family heirloom served only to emphasise the sad contrast between its survival and the disappearance of all the other paintings from Nunney.

It was beginning to appear that there might have been a concerted effort to conceal the connection between Henry’s family and their benefactors, Robert and Caroline, by dispersing their inheritance. Katrina and Richard certainly did seem to have avoided mentioning the art or the bequest of the house, or indeed Robert and Caroline, to their children. Why? Had they simply forgotten the inheritance, and the people, as the years went by? Or had they understood and acquiesced in a need to obscure the relationship between themselves and Robert Bateman?

It turned out that Amanda Kavanagh, back in 1987 when she was researching her Apollo article, had posed these questions before us. Jennifer showed us a letter that Kavanagh had written to Katrina, having traced her as the daughter of the executor of Robert Bateman’s will, to ask if she knew anything about the fate of Robert’s work left in his home and studio after his death. She enclosed some images of Robert’s work, and emphasised the level of critical recognition his work was achieving in the international art world. She described the portrait of Caroline as ‘really wonderful’, and claimed it originally hung at Nunney. If Kavanagh was correct, it must have formed an unforgettable component of the interior of Katrina’s former home.

Katrina was eighty-two when she received this letter. The most obvious person for her to involve and consult was her granddaughter Jennifer, who lived with her and whose interest in family history would have guaranteed her enthusiasm. But Jennifer had known nothing about it, only finding it among her grandmother’s papers after her death, with no pictures attached to it. They had never even discussed it. If Katrina had forgotten the paintings, then the letter with its images and startling re-evaluation of them would surely have jogged her memory. However, she had just put it away and said nothing. Jennifer was unable to tell us even if Katrina had replied to Amanda Kavanagh or not. The obvious way of solving the puzzle was to contact Amanda Kavanagh, and we did so. Although she remembered her correspondence with Katrina, she had no record of any response from her. We also checked the end of the Apollo magazine article where Kavanagh had listed her sources. Katrina was not mentioned, nor was there any evidence within the text of information she may have supplied.

In the circumstances, we had little option but to conclude that Katrina had chosen not to reply, and not to mention the letter to Jennifer or anyone else in her family. Considering the possible financial implications for her descendants, and its direct relevance to her own life story, it is hard to see what led her to this decision. Did she feel that responding to the questions it raised would involve delving into something private that she perceived as potentially damaging to herself and her relatives if it were publicly known? It seemed as if the resurrection of Robert, through the recognition of the quality of his work in the late 1980s, had appeared like a ghostly spectre to his living relations, who had buried all trace of the connection between their family and him beneath a conspiracy of silence that even embraced their children. How far this had been deliberate, and what had motivated it, was fast becoming the question at the core of our search.

![]()

Fig. 116. The grouped graves of John, Rose, Robert and Caroline in Whatley churchyard.