4

The Fairy Tale Between Fabula and Historia

The preceding chapters can be considered a long but synthetic voyage through the principal stages in the rise and forging of Irish narrativity, clearly from the point of view of what we have defined as the fairy tale. From this voyage, it seems to me that a definite link has emerged between the narrative elaboration pertaining to a folk in the broadest sense and the events, more or less historical, of the Irish land and nation. So consolidated was this link that it convinced the main advocates of national independence to see in this patrimony of oral tales the most efficient means to restoring a strong identity to a people who, if they were to give life to a coherent and incisive national rising, had necessarily to strengthen their roots in the purest native tradition. In this narrative patrimony lay hidden the most consistent and unique part of the immense heritage—cultural in the broadest sense—that the Irish had inherited from the past. This was a past, moreover, that could not be reconstructed according to objectively historical criteria,1 but rather required the persistence of a quality radically innate to the Irish spirit: the absolutely fundamental value attributed to the narrative act, which was jealously conserved even at the cost of regressing to a prescientific dimension, to the irrational, in purely Celtic style.

The congenital narrativity of the Irish people has already been discussed. This concept must now be reviewed and analyzed more specifically as regards its sources before we can begin a deeper exploration of the particular, indicative context that, from the point of view of a discourse on narrativity, is the fairy tale. Although the fairy tale presents the most suitable form with which to represent the particular historical and cultural stratification of Ireland, one should not undervalue its eminently recreational function, in the double sense of the “re-creation” of the real and of entertainment. This function, in both cases, assumes even more value in the context of the Irish countryside, at least until the beginning of the twentieth century,2 in which poverty and the monochord scansion of time could be opposed in a practically univocal manner by means of storytelling, an activity of the spirit (in the words of Jolles) characterized by its seriousness. This last concept is valuable, insofar as it leads us well beyond the distorted idea of the fairy tale, in the strictest sense, that was widespread in Europe following work of the Grimm brothers. This concept of associating the tale with an audience of children never took root in Ireland, even up to the present day. Those tales that various collectors before Yeats gathered from the voice of the Irish peasants in the course of the nineteenth century were an integral part of contexts made up primarily of extremely attentive adult listeners.3 Far more so here than elsewhere, the universal, aboriginal value of storytelling had been preserved. An Irish proverb asserts that “it is a bad thing not to have some story on the tip of your tongue”:4 homespun wisdom that seems to convey in the most vivid terms possible the spirit of a people for whom there is no need for a real barrier between reality as it is lived and as it is transported into storytelling. In Ireland, the social integration of any individual depends on his being capable, at any occasion, of offering to the community his personal contribution to the construction of a collective patrimony of stories. Should a native capacity as a fabulist not come to one’s aid (either by giving life to a new tale or recalling one from the depths of memory), it is always possible to resort to events from one’s own biography, since, once lived, they are immediately classified as material that can potentially be narrated. This is by no means a singular observation, as can be seen from the remarkable number of examples drawn from Irish tradition. I am referring to the many tales focused on the subject of the man without a story, who, within the narration, becomes a real character only when he is made to live, in the first person, a fairy experience: experiences of another type could definitely be narrated, but were less effective in riveting the public’s attention. Only the fairy tale is able to magnetize the interest of any listener. Into it flow all the data and values having the power to make recognizable and to strengthen links between individuals and, at the same time, provide escape into a parallel universe, another world—frequently very close by—in which are conserved the dreams and illusions of an entire community.

We have already seen how historical and pseudo-historical contexts and the narrative genres pertaining to them meet in the fairy tale. The theoretical possibility of the fairy tale is insolubly linked to the existence of multidimensional reality, on the basis of which the reality to which it refers is seen to consist of two qualitatively distinct levels—normally separate—that enter into contact when the fairy tale, as a sort of neutral ground and place of abnormal movement, offers its intermediation. It comes to the fore when the unity of being proper to Myth disappears, outdone by the advent first of a legendary and then of a historical context, contexts that assume given valency depending on the use made of them in the classification of Celtic literature. This is based on four main cycles, each of which gives witness to (in fabulous key, but frequently with a clear historical intent) the complex story of a nation that, only with the advent of Christianity, turned to writing.

If we take into consideration again the sections into which Yeats divides his collection, we will observe that each of them refers to the existence of a certain category: human, animal, and, above all, supernatural. They all have a specific identity, and sometimes are antithetical to each other. Each of them reflects a given aspect of folk-lore, which assumes consistency in that listeners to the tale are held at a certain distance from the figures evoked, who become representatives of a heterogeneous world into which, without the intermediation of the fairy tale, it would be impossible to enter. This may occur in a direct manner, or in an indirect one, as in those categories based on a human character who enters into contact with another world—for example, saints and priests, kings, queens, princesses, earls, robbers, and warriors (but not witches and fairy doctors, because these human figures themselves are repositories of supernatural powers).

If the meetings and visions that compose the tales put together by Yeats did not denote a more or less elevated degree of extraordinariness, they would not display all the weight attributed them. Converging in them are all the data and values that permit a genuine dialectic among the most distant planes, in time, space, and in system of reference, that have sedimented themselves in the Irish collective tradition. This mode of proceeding, bypassing the continuum proper to a history in the strictest chronological sense, allows the storyteller and his audience (as well as those writers who approach the stories) to appropriate and interpret with the widest margin of liberty the inherited past. To determine the structure and significance lying at the basis of the fairy tale, it is necessary to identify the theoretical premises on which it operates, the nature of the material that it elaborates.

The Space-Time Coordinates of the Fairy Tale

But the People of Dana do not withdraw. By their magic art they cast over themselves a veil of invisibility, which they can put on or off as they choose. There are two Irelands henceforward, the spiritual and the earthly. . . . Where the human eye can see but green mounds and ramparts, the relics of ruined fortresses or sepulchres, there rise the fairy palaces of the defeated divinities . . . . The ancient mythical literature conceives them as heroic and splendid in strength and beauty. In later times, and as Christian influences grew stronger, they dwindle into fairies, the People of the Side; but they have never wholly perished; to this day the Land of Youth and its inhabitants live in the imagination of the Irish peasant.5

This passage taken from a work—half tale and half essay—by Thomas W. Rolleston, an exponent of the Irish Revival whom we have already met, is definitely emblematic, since from it can be gained a sufficiently clear idea of the foundation from which the edifice of the fairy tale takes origin and on which it is built. This synthesis is a particularly fortunate one, because it brings to our attention the sources from which are born not only a narrative genre, but also the cultural code of an entire people.

What is described is a kind of epochal alternation between a declining and a rising civilization. Rolleston (who, as we know, had a certain knowledge of the medieval manuscripts, which he employs as the only usable documentation on which to base his approximate historical construction) refers to the conflict between the primitive colonizers of Ireland, the Tuatha Dé Danann, and a race of new invaders, the so-called Milesians. The success of the latter, albeit fabulous to a degree, is of great importance in the history of the island: tradition has it that the Milesians stood at the origin of the Irish people. In parallel, we observe the definitive decline of the mythical age (properly speaking) and the beginning of what was gradually to become the History of the Irish nation, marked by a recognizable humanity that gradually imposed itself through the occupation of a space in which a group of superhuman individuals previously lived and to which they gave form. However, the alternation of epochs did not lead to the cancellation of what, for a long period of time, had distinguished Irish reality. The victor did not assimilate a number of characteristics of the loser, nor did the loser adapt to living subordinate to the victor. Instead, the victor took possession of the visible, earthly space and the loser abandoned the field—but did not abandon Ireland, since he retired into an entirely new invisible, unearthly dimension or, let us say, a subterranean one. In substance, the race of the Milesians superimposed itself on that of the Tuatha Dé Danann not only in the temporal sense, but also physically: it is by no means accidental that one speaks of two Irelands. A space subdivided into two reciprocally opposed but coexisting worlds came into being.

This coexistence is not usually perceptible, in that, as Rolleston emphasizes, from the human point of view (which affirmed itself after the Milesian invasions), it cannot be located. All that appears are hills and architectonic ruins, the sites to which was transferred the reality of those who had been the uncontested masters of the entire country and its sole inhabitants. On the contrary, the latter, gifted with powers unknown to man, have the capacity to make their presence visible, or rather to become, exceptionally, perceptible to the natural senses. One is dealing with a clearly divine race, at least from the point of view of the literature preceding the advent of Christianity, as Rolleston specifies, or rather in view of the characters forming that part of the narrative tradition set in a pre-Christian epoch. In parallel to the affirmation of the faith imported by St. Patrick, in part of the literature but above all in popular tradition, on which the oral transmission of fairy tales depends, the Tuatha Dé Danann are reduced to the rank of Fairy Beings. Whether considered divine figures or fairies, their significance remains the same. In one or the other form, they are products of a supernatural reality, coexisting with humanity and acting as repositories of qualities and values that reflect the aspiration to transcend from within the narrow confines of a purely material world. It is in this respect that Rolleston speaks of a Land of Youth, the Tír-na-n-Og, under which Yeats lists a section of his collection—in other words, Fairyland. And we have already discussed how great, not just in the literature, but in the entire Celtic, and by consequence Irish spirit, is the anxiety for the absolute, the infinite.

I agree with Rolleston when he interprets the Milesian invasion as a sort of caesura imposed by a rereading of the narrative tradition in the Christian key, on the basis of which it was inadmissible to connect the origin of the Irish people with ancestors of an explicitly pagan nature.6 I am also convinced that the Danann were overloaded with divine connotations, so that their defeat would become all the more disastrous, thus suggesting the idea of an omnipotence that becomes apparent only when compared to that of men who, later, would convert to the True Faith. However, they have remained, at all levels—from the collective imagination to literary elaboration—imperishable symbols of a dimension proper to humanity itself, one that is not only pre-Christian, but more generally primitive, preceding so-called civilization, with all the limits that civilization has imposed on existence and the barriers that it has raised to destroy an aboriginal unity. Where a relationship is established between this primigenial dimension and the representatives of what has superimposed it, we witness the intersection, not only of spatial ambits, but also of temporal contexts, between an immanent and transient element, subject to historical becoming, and a transcendent and eternal one, pertaining to the sphere of spiritual being: between a continually mutable present and a past that tends to return, perhaps in an altered guise, on the basis of a transformation of the system of reference. But the significance underlying this type of relationship remains substantially unchanged.7

If we keep scrupulously to what tradition narrates, the Tuatha Dé Danann are not the first colonizers of the island; they are not, that is to say, the genuinely aboriginal race, before which nothing existed. The first sections of the Mythological Cycle, which in truth are extremely lacking in consistency, describe the alternation of at least three peoples who sequentially settled in the island, the last of which is named the Firbolg.8 However, none of them left tangible signs of their passage, thus extinguishing themselves when they were replaced by the next invader. The Firbolg have a certain importance in virtue of their unsuccessful war against the Danann. After this event, the latter assumed dominion of the island and the defeated race is lost from sight. However, they did not disappear as preceding invaders did, but, albeit in a condition of subjection, were assimilated (a concept that takes on a certain importance, as will be clarified further on). Thus, they did not install a parallel dimension, separate from, but coexisting with that of the newcomers. The Tuatha Dé Danann, therefore, found themselves in a reality organized on a single plane; theirs was a unitary Ireland, in which they were the only paradigm. Above and below them were no qualitatively different interlocutors with which to confront themselves, no past that had survived to offer an alternative to the order imposed by them. For as long as their dominion over Ireland lasted, they were the only conceivable plane of humanity. Their battles with the evil Fomorian, who frequently came from an indefinable elsewhere to contend their dominion, are not, in my opinion, the manifestation of a dialectic between two parallel dimensions of primitive humanity. They are instead the two sides—obscure and infernal (even demoniac, in the later Christian interpretation) and luminous and divine—of the same mythical dimension. Moreover, the Fomorian, having lost the decisive battle and being absolved of their function as a testing ground, were adopted by the narrative tradition to demonstrate the superiority of their adversaries and disappeared for good.9

The Tuatha Dé Danann, therefore, establish the mythical plane already mentioned as the indispensable point of departure for and foundation of the entire narrative tradition, in particular as regards the fairy tale. The latter can only originate after a mythical age, both in the temporal and causal sense. The fairy tale must draw from a mythical patrimony, but only after this has become the heredity of an indefinite past. For as long as a mythical context lasts, or rather the one-dimensional reality of the Danann, the tale can have only a single dimension in which everything is contained and in which everything is definite. This is because the mythical tale—and hence every narrative exemplar from the Mythological Cycle of the Irish tradition—is constructed following a univocal logic, framed by a unilinear conception of space and time organized along a single line, which can be represented, according to an elementary graphic exemplification, as shown in figure 4.1:

Figure 4.1.

The “O” (= Origin) indicates the moment at which the Tuatha Dé Danann settled in Ireland and therefore that point in the past (obviously not datable, at least according to rigid historical criteria) in which the mythical age began, and consequently, also began the possibility of mythical storytelling itself. The half-line, which takes in an indefinite arc of time, represents therefore a universe organized on the basis of a unitary scheme, in which exists only the reality imposed by the Danann. This lasts until an upheaval occurs drastic enough to definitively upset the status quo. Hence, we must imagine the entire history of the mythical characters as taking place along this line, characters for whom there is no other system of reference than their own. Because of this, everything narrated in regards to them takes place in an internal context that does not contemplate the “shifting of a persona across the borders of a semantic field.”10 This semantic field is single one, an open space in which the concept of the boundary is unknown insofar as its horizons are universal and totalizing, and there is no reason for a distinction to be made between the ideal and the real.

But myth—or rather the world fashioned by it—as a configuration of an aboriginal and ideal dimension has to reach a conclusion so that it can give way to the properly human events of History. This takes place, as already mentioned, by means of an invasion of individuals from an external world,11 who come to permanently disturb the equilibrium preserved until then by the Danann. The Milesians conserve almost every characteristic of the latter, with the fundamental distinction that each of these characteristics is set in a context connoted according to canons of humanity.12 It is here that the mythical unity is disrupted and the evolution of the two-dimensional space begins; from now on, the historia and fabula of the Irish tradition will be framed. The withdrawal of the Tuatha Dé Danann into a supernatural dimension (that we can call Fairyland and is to be found in subterranean realms beyond the sea, as well as in more accessible places, in strict contact with man, although going normally unnoticed) unveils for the first time the persistence, albeit in a new guise, of a past that no longer allows itself to be overcome and assimilated by the present, a heredity that does not live only in the memory of the mythical tale, but coexists with the new reality, thus offering the possibility of a direct confrontation between two semantic fields. The horizon against which the tales of the Ulster Cycle and the Fenian Cycle are framed can be represented as shown in figure 4.2:

Figure 4.2.

In this case, the “O” indicates the moment at which, having been definitively defeated, the Tuatha Dé Danann cede dominion over the visible Ireland to the Milesians and withdraw, as demonstrated by the perpendicular line linking the half-lines, into a parallel dimension This is invisible, both in virtue of its supernatural significance and the superimposition on it of what, from now on, will be configured as reality—or rather the norm, on the basis of which this reality is definite and objective and drives the preceding mythical norm into an indefinite and subjective field. From this point of view, the distance between the two half-lines is explained. They represent the separation between the planes, which continue separately, according to specific values and parameters, as indicated by the use of two different colors representing the qualitative difference between the two contexts.

This is the space–time system within which the fairy tale is conceived, or rather within which it is conceivable, since, although the environment suited to its birth has been installed, the borders have not yet been passed. The intersection of the two semantic fields has not taken place; or rather, the fairy movement has not occurred to interrupt the stasis in which the tale will otherwise find itself. For as long as the two half-lines remain parallel and distant from each other, the fairy tale will exist only in potential, whereas in reality, one-dimensional tales will continue to be handed down, whether mythical or legendary. Regarding the use of the latter adjective, it must be specified that I am referring to the tradition pertaining to the Ulster Cycle and the Fenian Cycle, included within this category to evince their nature as intermediaries between Myth and History, and also to emphasize the heroic character of their protagonists. This said, it is only when the plane of Myth and the plane of Legend, when mythical and legendary characters meet, or when the two half-lines cross, that one may speak effectively of the fairy tale. It will cover the vast part of legendary tradition in which are narrated the feats of human heroes who go out to meet those characters, raised to a divine or semi-divine level, who make up Fairyland, and also, in the opposite direction, when the Tuatha Dé Danann come out into the open to join up with man. In both cases, storytelling will become the locus in which two opposed semantic fields meet, and hence the means through which the storyteller—and with him an entire community—can reappropriate an ideal dimension that once was real. In the fairy tale, for a certain period of time, the aboriginal unity is recomposed.

However, the legendary age is also destined to end, giving way to a third phase of history and of Irish narrative tradition. The legendary age is supplanted when a more properly historical age comes into being, whose origins in my opinion are to be found when St. Patrick began his preaching.13 With the advent of Christianity, one enters, gradually but inexorably, into a new context, in which the points of reference change radically as do, consequently, the nature of the figures involved, who assume entirely human connotations. With St. Patrick, in short, one has entered a historical dimension (and the relevant narrative cycle is defined precisely historical) that superimposes itself on the two dimensions inherited from the pagan past, which is framed within new schemes, but certainly not cancelled out. The representatives of Myth, demoted to fairies because their primitive divine character is obviously irreconcilable with the new faith, and the protagonists of Legend, only now retrospectively assimilable as the heroes of an ideal humanity, do not disappear from a horizon as spatial as it is conceptual. Instead, they withdraw into two parallel dimensions that act as two alternatives—coexisting, yet invisible—to the reality imposed by the advent of History. Space and time are hence organized on three planes, which may be represented as shown in figure 4.3:

Figure 4.3.

This time, the “O” indicates the moment at which, beginning with St. Patrick’s first sermons, the Christian faith affirmed itself in Ireland, thus making the pagan dimension of legend sink to the same level as it had imposed on the mythical dimension. The latter, for its part, is consequently distanced even more from the light of day—or rather, its distance from objective and visible reality increases insofar as it becomes almost entirely fabula in comparison with something that is all historia. At the same time, its proximity to the legendary context, in which fabula and historia balanced each other, is greater. Naturally, these are absolutely relative concepts, expressed from a viewpoint internal to the narrative tradition, which, along its path, reflects in broad outline the process leading from a purely fabulous dimension to an ever more historical one, thus reflecting the gradual passage from orality to writing. But, and this is the important point, we are in the exceedingly mobile field of narrative and of culture, whose impatience regarding rigid schemes evinces itself in the virtuous circle of narrativity, which is capable at any moment of disrupting a presumed equilibrium.

This equilibrium based on three dimensions, in which, on each of the parallels, an independent tradition of one-dimensional tales can at any moment develop, is in fact entirely disrupted by the fairy tale, which now avails of a more complex, richer horizon within which to unfold its convergent dynamic. This new horizon, as suggested by some sections of Yeats’ collection, makes it necessary to take into consideration the presence of a fourth dimension, one that is transcendent and celestial, linked to the Christian hereafter and hence to angelic or diabolical figures, or to specters that originate from a reality considered superior. From this viewpoint, the mythical Otherworld, albeit supernatural, must be interpreted in terms of immanence, situated at best halfway between heaven and earth, as evidenced by the popular identification of fairies with fallen angels.14

The Dynamic Established by the Fairy Tale

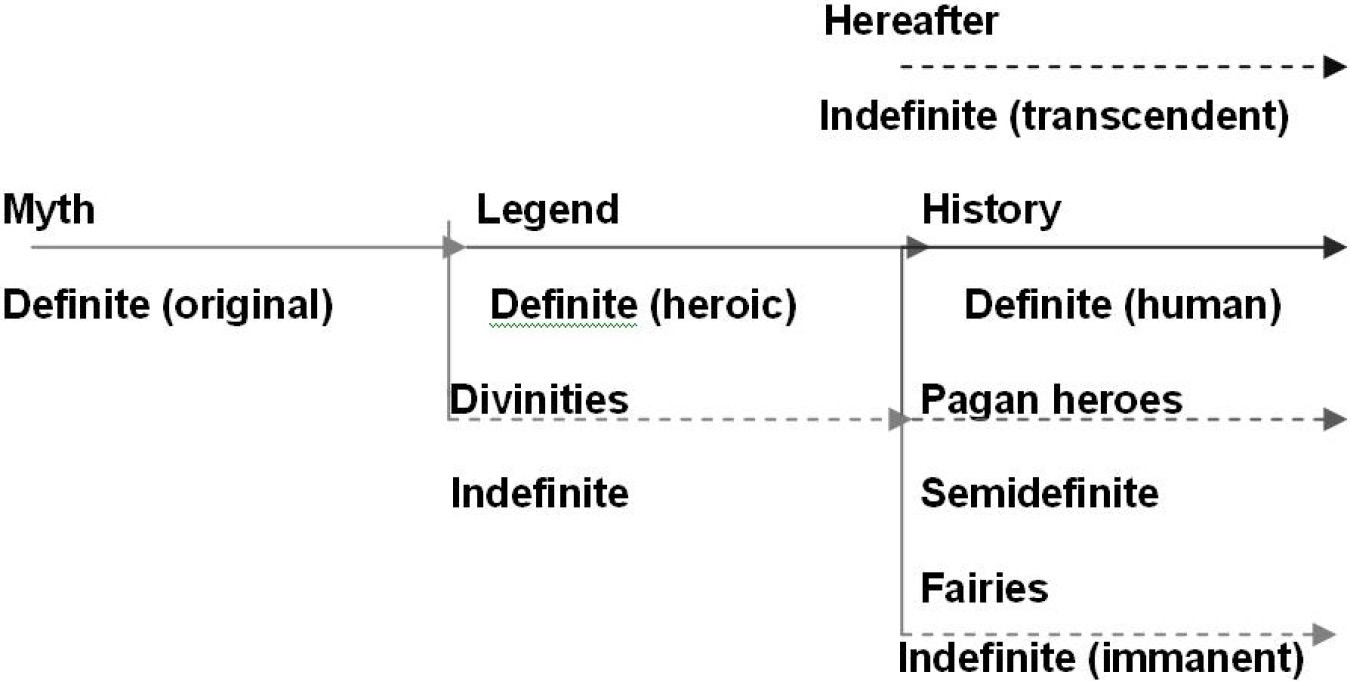

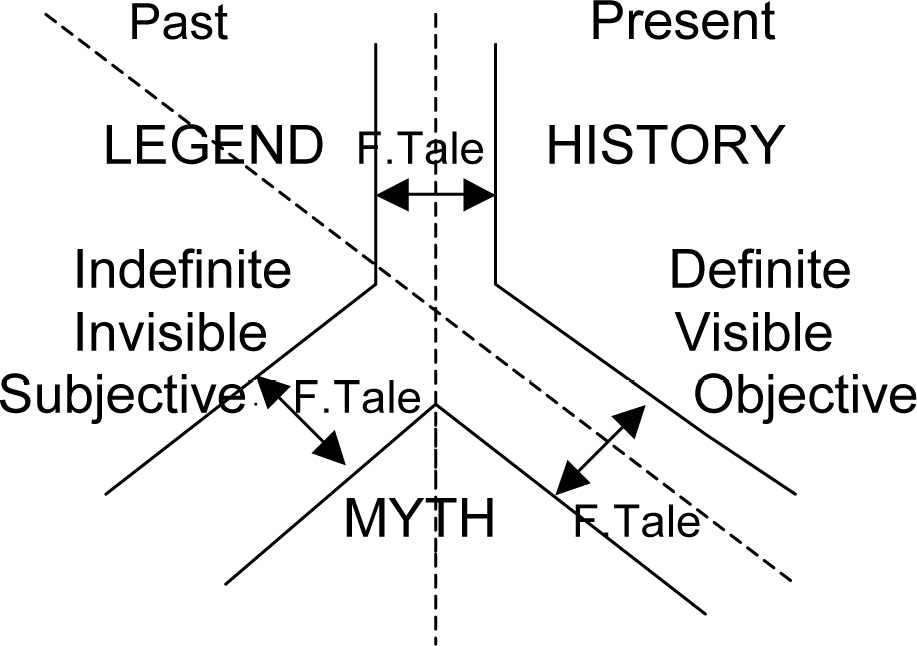

At this point, we can claim to have a complete picture of the space–time context within which the fairy tale operates, and this permits us to verify how this narrative genre, in its dynamic, is able to break down the semantic barriers imposed by a certain historical and narrative evolution. It can display, in its substantial unity, a tradition that, in effect and despite the fractures identified above, conserves an underlying continuity, which is frequently demonstrated in contexts other than the fairy tale.15 Thus, figure 4.4 summarizes in overall terms what has been discussed until now and should be interpreted simply as an attempt to offer a general model in which the theoretical presuppositions of the creation and circulation of the fairy tale may find an organic and intelligible systematization. It should be emphasized again that the tradition of the fairy tale is intimately connected to the reconstruction, sub specie narrativa, of the phases that led to the formation of the Irish nation.

Figure 4.4.

In contrast to the preceding examples, it is here possible to gain an overall vision, both in extension and depth, of the development of Ireland as described in the four principal cycles of which the narrative tradition is composed. This time, conceptual categories have also been employed, on the basis of which it is possible to interpret, depending on the angle of observation, each of the dimensions that gradually complete the horizon within which the fairy tale operates. The basic principle on which the model is founded is the opposition between the definite and the indefinite (the notion of the semidefinite indicates the intermediary nature of the legendary dimension in relation contemporaneously to the mythical and historical dimensions), an opposition that, as can be seen, alters its terms when the contingent situation alters. The definite is the level of the objective, the visible, the present, from the viewpoint of those who, in a certain space–time context, have imposed their vision of reality, thereby creating a norm that relegates the previous one to the level of the indefinite, to a subjective dimension, invisible and pertaining to the past, which may no longer be directly drawn on, unless by a movement that interrupts the established equilibrium. The definite, in its evolution from Myth to Legend to History, always remains at the top level of the diagram, indicating its imposition over those dimensions that, once supplanted by a new definite, sink lower into the field of the indefinite, where the broken line represents the relative consistency of a reality that can subsist only insofar as the higher level one admits of its existence. The issue is obviously different when one deals with the transcendent indefinite, since it is a category that has the same reason for existence as the historical dimension introduced by the advent of Christianity, and thus must be situated at the higher level, in a position appropriate to what should be understood as the indispensable otherworldly norm on which the vision of the world introduced by the historical definite is founded.

In the diagram, it is also possible to follow the evolution that the exponents of each level have undergone in accordance with the alteration of the norm of reference in which, in the course of time and of the tradition, they have gradually been framed. As long as one remains in the higher part of the model, each level represents a type of humanity, which passes from an aboriginal level in Myth (a sort of primigenial race from the age of gold) to a heroic level in Legend (distinguished in turn by the giant and monolithic heroes of the Ulster Cycle and the less magnificent and more fictional heroes of the Fenian Cycle), to arrive at humanity as it is conceived of today and that affirmed itself historically in the Christian age. This same humanity, as already mentioned, declasses the exponents of myth to the range of fairies, after they had been made divine in the legendary and pagan ages. The heroes of Legend, although not surviving properly speaking in a real parallel world, as do the fairies, remain nonetheless within the horizon of the narrative tradition of the fairy tale, both directly, when the return of one of them from Fairyland is narrated (as in the case of Oisin, who meets St. Patrick), and indirectly, when the tale is told of sublime characters who, by virtue of their characteristics, recall the legendary context, particularly if it is contrasted to a popular ambit. In any case, and above all as regards the heroes of the Fenian Cycle, one can easily observe this assimilation on the historical plane of characters pertaining to the legendary age by a tradition that reworks its subjects in a Christian key. The boundaries between one plane and another of the edifice of the fairy tale are not impermeable, because, inevitably, the final word awaits whosoever avails, on the concrete level of storytelling, of what these planes contain.

Using the theoretical premises thus laid out, or rather the static factors on which the fairy tale is founded, one may now approach the dynamics of its composition, enucleating its fundamental structure so that we may begin an analysis aimed at opening up a new perspective on the relationship between oral tradition and written elaboration, between the popular and the authorial tale. But before setting out on this examination, which will occupy the next chapter, I wish to clarify through a final graphic representation in what way, in my opinion, one should individuate the space that the fairy tale occupies in the categories analyzed up until now. My idea is that it stands as a species of intermediate space, not only with regard to its function, but in the literal sense. If we consider that Myth, Legend, and History individuate three spatially and temporally distinct contexts, separated by semantic barriers (I exclude, for expositive purposes, only the transcendent dimension of the Christian hereafter, which is implicitly included in a context that extends from History, due to its present and substantially objective connotation, to Myth, due to its indefinite and invisible nature), then the fairy tale occupies the open space between the closed systems just mentioned. This is a communal open space, in which exponents of any of the closed spaces may converge according to a modality that we shall call escape, a term whose exact meaning will be explained later. Escape concretizes itself in border zones, such as a wood, the banks of a lake, or ancient ruins, most probably in the liminal moments of night and twilight. Whosoever escapes from his plane does not enter immediately into another, but rather into this sort of free zone represented by the fairy tale, from which it is then possible to proceed by means of a genuine invasion, caused by a character passing the confines of a new dimension: this is the case when a character, rather than remaining on the banks of a lake, goes to the bottom, thus entering into an area pertaining properly to a fairy dimension, or when, vice versa, an indefinite character penetrates a house inhabited by human beings.

In the final scheme proposed here (see figure 4.5), the various combinations on the basis of which one can identify a fairy tale are contemplated. As can be seen, there are three. In order of their appearance they are Myth-Legend, Legend-History, and History-Myth (in the last pair the relationship of History-Christian Hereafter is implicitly included), as if to trace a circle closing on itself. Moreover, the three space–time dimensions are set out in such a way as to connect them precisely to the concepts previously adopted to illustrate the fundamental nature of the oppositions that they represent, but also to evidence (through the broken line) how these concepts pass gradually and fluidly from one dimension to another.

Figure 4.5.

Notes

1. In fact, in the tales that narrate mythical or legendary events, rather than historical reconstruction, one finds anthropological data pertaining to the society and culture in which the tales were elaborated. At the least, it is necessary to consider various aspects linked to the creation and fruition of the single tale. Cf. Kay Milton, “Irish Hero Tales as a Historical Source: An Anthropologist’s View,” Occasional Papers in Linguistics and Language Learning (Approaches to Oral Tradition) 4 (1978): 88: “Whether a particular narrative can be treated as an account of things happened in the past, as an entertaining story, or as a comment on what people hold to be ultimately true depend, not on the content of the narrative, but on what people do with it, the way in which it is brought to bear by them in social life. At the same time, what is said in a narrative will depend on the purposes for which it is used. The content of a narrative can only be understood, therefore, with reference to the social context in which it is told, learned, written down, or whatever.”

2. That is until progress imposed new, more sophisticated forms of entertainment. Cf. Ó Danachair, Stories and Storytelling in Ireland, 111: “Before the penetration of modern media of entertainment into the countryside, the folktale took the place now filled by the glossy magazine, the novel, the radio and television, not forgetting, of course, the theatre and the cinema. With the coming into the countryside of all of these, the storyteller has lost most of his audience to the newer forms of entertainment. There still are storytellers, but now they must be sought out and coaxed to tell their tales, where formerly they held court night after night—especially in the long winter nights.”

3. Cf. Gose, The World of Irish Wonder Tale, XIX: “In Germany the brothers Grimm came upon these tales through nurse-maids and old wives, who told them to children more than to adults. The situation was quite different in late nineteenth-century Ireland. There the men (and a few women) were the proud bearers of an active oral tradition. Since the tales were often told long into the night, young children were usually neither present nor welcome during these sessions” (my italics). Preserving a tradition of fairy tales is not simply an adult business, but a question of pride.

4. Zimmermann, The Irish Story Teller, 519.

5. Rolleston, Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race, 136–37.

6. See ibid., 120–21.

7. Cf. Carolyn White, A History of Irish Fairies (Dublin: Mercier Press, 1976), 17: “Mighty gods [the Tuatha Dé Danann] they were, of gigantic proportions, and humans honoured them as such. But when they went underground and became known as the fairies, human perception of them altered . . . . The size with which fairies appear to a mortal is proportionate to the belief that the mortal has in them.”

8. In order to deepen a theme not strictly connected to our research here, see Rolleston, Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race, 96–107.

9. See ibid., 117.

10. Jurij Lotman, The Structure of the Artistic Text (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1977), 233.

11. The journey that brought the Milesians from their native land to Ireland, in the tradition, takes the form of a passage from death to life. See Rolleston, Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race, 131–32: “They come from ‘Spain’—the usual term employed by the later rationalising historians for the Land of the Dead. . . . Some mysterious law, indeed, brings together in the night the great spaces which divide the domain of the living from that of the dead in daytime. It was the same law which enabled Ith [Miled’s grandfather, the Milesian’s progenitor] one fine winter evening to perceive from the Tower of Bregon, in the Land of the Dead, the shores of Ireland, or the land of the living.” The second passage, in which Ireland seems like a promised land in contrast to an external space inundated with the idea of death, is taken from D’Arbois de Jubanville, Irish Mythological Cycle and Celtic Mythology, 1903.

12. See Rolleston, Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race, 138–39.

13. Cf. Patrick K. Ford, “Aspects of Patrician Legend,” in Celtic Folklore and Christianity: Studies in Memory of William W. Heist, ed. By Patrick K. Ford (Los Angeles: McNally and Loftin, 1983), 29: “The problem of Patrick is a very vexed one, as Celtic scholars know. Most studies have concentrated on historical issues, including the authenticity of the two works attributed to the saint and the sources available to his earliest biographers, Muirchú and Tírechán, both writing in the late seventh century—perhaps. But what interests the folklorist and the mythologist is not the historical problem but the persistence of a symbology in the developing legends concerning the saint, whom tradition has credited with the conversion of the Irish people.” The question of the historical consistency of St. Patrick should in no way challenge his deep symbolical significance. In the ambit of an internal study of the Irish narrative tradition, the figure of the saint should be analyzed in terms of its functionality in an eminently narrative context, beyond any other implication. In substance, it is his character and not his actual person that acts in the present study. Or, at least, the first prevails over the second, considering moreover that it is far more verifiable than the other.

14. Yeats in the introduction to the section “The Trooping Fairies,” questioning himself on the origin and nature of the fairies, furnishes three hypotheses, as different as they are dependable (Yeats, Irish Fairy Tales, 1): “‘Fallen angels who were not good enough to be saved, nor bad enough to be lost,’ say the peasantry. ‘The gods of the earth,’ says the Book of Armagh. ‘The gods of pagan Ireland,’ say the Irish antiquarians, ‘the Tuatha de Danan [sic], who, when no longer worshipped and fed with offerings, dwindled away in the popular imagination, and now are only a few spans high.’” Each of these hypotheses reflects not only a specific point of view, but also a whole group of meanings and values associated with the fairies.

15. See, for example, what is said regarding the hagiographic genre in Ford, Aspects of Patrician Legend, 30: “The Lives of the Irish saints not only continue the tradition of heroic literature, but have in some degree borrowed from the sagas even their motifs.” Although it is true that St. Patrick inaugurated a new era for Ireland, it is also true that the preexisting tradition brought all the weight to bear of its traditional heritage.