5

The Process of Composition of the Fairy Tale

The graphic model appearing at the end of the previous chapter is probably the best point from which to begin an analysis aimed at identifying the dynamic factors underlying the composition of a fairy tale. This follows the conviction that we will be able to isolate a fundamental structure for all the single examples of fairy tales forming part of the Irish tradition, trusting in the representativeness of the texts in Yeats’ and Stephens’ collections. These texts, presenting an extremely wide typology, both thematic and formal, reveal themselves to be a field of research and comparison ideally suited to our objectives. Moreover, having at our disposal a number of texts in which, in one way or another, orality and writing, folklore and literature, fuse together, opens a wider view to our research, permitting us to trace a principle of composition, as functional in the oral/popular tradition as in the written/literary one. Thus, in practice, from an analysis of the fairy tale we can gain an integral understanding of the narrative phenomenon.

Our model is the most appropriate point of departure for the scope of this chapter because, on the one hand, and in virtue of the analysis made until now, it provides the most suitable image of the theoretical conformation that has been created in the course of a process of evolution that took place on both the levels of historia and fabula, a conformation that forms the static platform—or, let us say, the constant background—on which the fairy tale operates. On the other, the model already suggests an idea for identifying the more properly dynamic valency of the fairy tale, not so much in its faculty for connecting qualitatively different (if not opposed) levels of reality, but rather in its situation in a substantially indistinct ambit, an intermediate space in which the barriers between one context and another fall and the founding principles of the initial situation are cast into doubt or reworked. In the scheme under discussion, one notices three bi-univocal vectors connecting the three dimensions of the Irish tradition (keeping under consideration the implicit presence of the fourth dimension, the Christian Hereafter, not included for reasons previously explained). These represent, more than bridges linking in one direction or the other, spaces that otherwise would remain separate, the movements of these spaces, through their exponents, enter into contact, converge, and situate themselves on the same level. This is because the fairy tale is a phenomenon that disturbs an equilibrium imposed in a contingent space–time dimension. This phenomenon is capable of manifesting itself because it avails of a territory of its own in which to attract the elements—or rather the characters—that are the depositaries of the subsisting order on the near side of the semantic barriers erected over the course of time.

In the Introduction, I attempted to lay out—albeit upon an expansion of the traditional current of thought and study—a certain idea of the fairy tale, an idea that led me to recognize some fundamental characteristics of a genre that, as seen, left its decisive mark on the entire narrative tradition examined until now. This idea derives from the multidimensional context that has just been illustrated, but becomes operative by means of a certain structure that I have been able to distinguish from an analysis of the entire collections of Yeats and Stephens. Setting out on a path inaugurated by Propp, I have attempted to individuate a limited number of fundamental functions that might lie at the basis of the fairy tale’s composition, a field in which—although larger than the nonetheless extended one of the tale of magic studied by Propp—it is even easier to be overpowered by the idea of an overwhelming variety and variability.1 In effect, the proliferation of Irish tales endowed with their own specificity, but also the elevated quantity of variants of the same narrative type, pass a threshold beyond which it seems pure sacrilege to attempt a theorization of a Structuralist kind. We find ourselves facing a natural predisposition to a potentially unlimited extension of our area of examination, and a relative, constant enrichment of form and content on the part of the frequently mentioned phenomenon of narrativity. This phenomenon, nevertheless, is able to operate profitably since, from its origins, it has acquired a fundamental structure that offers, in the case of the fairy tale, a sort of internal stability, starting from which it has been possible to definitively perceive an entity that we now can undeniably assume is a narrative tradition. The fairy tale maintains its continuity despite the constant, natural evolution of themes, forms, and paradigms precisely due to the persistence of an underlying structure; it is able to preserve in time a characteristic mode of acquisition of reality connected to a determinate narrative genre. Once organized according to the scheme we are about to examine, the fairy tale has not only forged its own particular identity, but has also established a model of reference for other narrative genres.

The model we wish to propose here, precisely because of the theoretical premises that arose in the last chapter, is given much support by the spatial conception in Lotman’s work. Particular importance is given to the idea that “the structure of the space of a text becomes the model of the structure of the space of the universe,” while the internal syntagmatic structure of the elements within the text become the language of spatial simulation.2 What does the fairy tale operate on if not on a spatial organization that has developed according to the dictates of a tradition born from the meeting between a historical discourse and a narrative one? When Lotman states that “the spatial order of the world [in a text] becomes an organizing element around which its non-spatial features are also constructed,”3 does this not seem to suggest that we should see in the fairy tale a structure designed to furnish an explicit image of the concepts operating in the implicit underbelly of a tradition, one not disposed of other means to express its contents in perceptible form? Lotman himself refers to the work of art in general as a translation, by means of which, in a finite space, the image of an infinite world is given.4 The fairy tale is likewise oriented toward the exploration of an infinite world, while remaining nonetheless radically rooted in the finite world in which it is elaborated. Through this typology of tale, the narrator detaches himself temporarily from the definite, from a space delimited by known confines, and transfers himself and his public, by means of exemplary characters, into the indefinite, a space in which lies all that, initially at least, it is impossible to define according to preestablished criteria. This space is unknown, or only partially known, and individuated by Myth, Legend, and the Christian Hereafter; these are loci modeled by tradition, as many dimensions with which the exponents of History come into contact and question themselves. This happens thanks to a movement in space (and, implicitly, in time) that is not figurative but real, clearly in terms of a logic internal to the tale, even though, given the ambiguous relationship that a narrative of folkloric origin has with historical truth, this logic might be subject to expansion. One should consider in particular the case in which the narrator and protagonist of a fairy experience are the same person, a case in which the narrative movement coincides with a historically probable, albeit debatable, event.

But, leaving aside these issues connected to the concrete and specific reception of a tale in a given context, what is of primary importance in general research is the identification of those functions—or rather the constant quantities—making up the fairy tale and adopted by it to appropriate the space–time context delineated until now. To reach this end, once again, a direct approach to the Irish narrative tradition is indispensable. A direct approach makes it possible to recognize an emblematic tale, one capable of establishing itself as a model for all others and of offering an outline on which it is possible to elaborate a hypothesis regarding underlying structure. As if to demonstrate a sort of conscious self-referentiality, it is the narrative tradition itself that undertakes it to clarify the foundation on which its multiform edifice is built. It explicitly leads us to the birth of the fairy tale, and this is made possible by a tale that, not by chance, is called the priomscel.5

The Triangle Composed of Étaín, Midir, and Eochaid, and the Origin of the Fairy Tale

Shortly after the arrival of the Milesians in Ireland, the tradition narrates an event that, for the first time, displays the bidimensionality that followed the withdrawal of the Danann to Fairyland, where the tale begins, as described by Rolleston.6 It is told that Midir, a prince of the once dominant race, takes the extremely beautiful Étaín as his second wife, causing the terrible jealousy of his first wife to explode. She transforms her rival into a butterfly, leaving her to wander from one part of Ireland to another until chance has it that, in this form, she ends up in a cup from which the wife of a Milesian chief is about to drink. At this point, Étaín’s fate changes radically and she is reborn from the womb of the woman as a mortal baby, forgetting completely her immortal past. Growing up, Étaín again becomes the symbol of beauty, so that she is given in marriage to the supreme king, Eochaid. Midir, therefore, first in the semblance of a brother of the king and then as himself, goes to Étaín to remind her of her past in Fairyland, describing it in all its properly mythical splendor. But the girl does not accept the invitation to go back to her first husband, since she is lacking the permission of her present husband, the king. Sometime later, the Danann prince presents himself at court to challenge Eochaid to a game of chess. After winning the last game, Midir asks as his prize to be able to embrace Étaín. The king, suspecting a trick, asks his guest to come back a month later. But when he returns, despite the ranks of soldiers drawn up in defense of the palace, he manages nonetheless to reach Étaín and to fly away with her, both in the form of swans. Hence, Étaín returns to her original dimension. Eochaid nevertheless does not resign himself to this state of affairs and, with the help of a druid, tries to discover where his rival is hiding with his bride. After nine years of battle, Eochaid finally forces Midir to surrender, but, in consigning him Étaín, the latter has her accompanied by fifty handmaidens, all identical to her, making it impossible for the king to recognize his bride. But Étaín, with a sign, succeeds in making her second husband recognize her, thus preferring to return to the human dimension, a choice in which we must probably read the definitive sanction of the passage from one epoch to another. Étaín undergoes this passage in the first person, and Midir and Eochaid are the first witnesses. In contending for the shared object of desire, they reveal the change that had recently taken place in the general plane of Irish reality.

In summarizing the adventures of this sort of love triangle, I have attempted to evince the fundamental passages, or rather those necessary for the identification of the functions suited to sustaining a discourse on the universal structure of the fairy tale. This structure is formed of series of actions performed by specific characters who become archetypes for all those who follow them in performing the same actions, leaving, despite the differences, a sort of trace that cannot be erased. Returning to an idea expressed by Frye,7 it seems fair to me to affirm that the model delineated by the priomscel, as an act of creation, is ultimately the only fairy tale really necessary for an understanding of the entire successive tradition—one that, made up also of tales that are chronologically anterior to those in question, refers to a model in which it can find its original identity. If the priomscel was elaborated after other fairy tales, this does no more than further underline its founding value, for which the tradition feels the need and which it hence reflects in a single tale, thus making it an exemplum in the deepest sense of the term. In this tale a narrative potential, latent in the new situation that had established itself with the separation between the definite and the indefinite Ireland, was finally liberated in a narrative act. The contrast between the mythical and the legendary dimensions is a paradigm that, through the figure of Étaín and the conflict that breaks out in her name, is manifested on a syntagmatic plane.8 This fundamental passage takes place according to the particular modality of the priomscel, a modality that, with the progress of the narrative tradition, assumes a universal connotation.

Let us go back, therefore, step by step, over the original fairy tale from a Structuralist point of view, such that this modality appear in its functional aspect, or rather as holding the constant quantities for the composition of each fairy tale. To make things clearer and to provide visual support for an analysis that follows the spatial approach adopted by Lotman, I will furnish an elementary graphic representation. Instead of a purely explanatory channel of the concepts theorized, this representation aspires to be an autonomous instrument for the structural analysis of the fairy tale.

An Analysis of the Priomscel and the Structure of the Fairy Tale

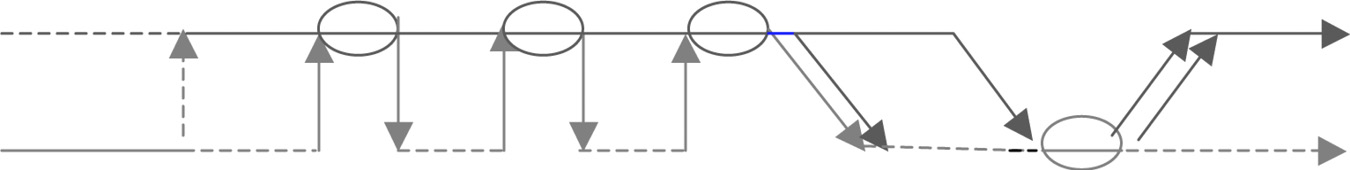

The situation presented at the beginning of the narrative lies within the mythical dimension arising from the defeat of the Tuatha Dé Danaan. In fact, the characters in the initial stages all pertain to Fairyland, and there is no connection between them and the definite plane of the Milesians, although it is implicitly present. The love between Midir and Étaín, and the jealousy of the first wife, are all set within the ambit of the mythical tale, and it remains such through all the vicissitudes faced by Étaín, before she falls into the noblewoman’s cup from which she will be reborn. In order to represent this first part, we must resort therefore to two parallel lines (as we did in chapter 4), but with two important modifications. The lines will no longer have a universal value, but will refer specifically to characters who, in the given fairy tale, represent both dimensions of Irish reality. The distinction between the continuous and broken lines, which previously represented the difference between a definite plane, depository of present norms, and an indefinite one, hidden in an abnormal condition, assumes now a properly narrative connotation. The solid line indicates the plane on which, in a certain moment, the narration focuses; the broken line indicates the situation that will obviously be beyond the narration, albeit present in its paradigmatic horizon. On these premises, figure 5.1 shows the structure the priomscel assumes in its opening stages:

Figure 5.1.

In this first sequence, the tale takes place in one dimension, since the fairy tale has not yet concretized. However, knowing the successive development of events, we are able to discover in this initial situation the necessary introductive form of the tale, or rather a fundamental function for the composition of the fairy tale. This function is of a static nature, both in regard to the properly dynamic development of the fairy tale and due to its one dimensionality. Considering all this, I believe that the label INITIAL STASIS is appropriate.9

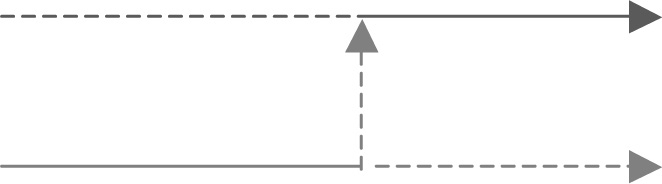

Étaín, who at the beginning belongs to the indefinite plane, after many vicissitudes ends up in the womb of a woman pertaining to the definite plane. Following this, she is reborn into new life, because she loses her previous divine nature and is transformed into a human being. As such, her adventures proceed, taking place now in the legendary dimension, with the mythical, in this phase, disappearing from the narrative. The scheme now assumes the form shown in figure 5.2:

Figure 5.2.

The line rising up to join the higher one presents what we may define as Étaín’s assimilation into the legendary dimension. This function is not fundamental to the fairy tale but has its importance insofar as it causes changes, also determinative, within the tale: it may even become indispensable in the institution of a dimension initially not contemplated in the narration. This does not happen here, but the way in which the main character alters her function diametrically in the tale should be emphasized. Her assimilation is permanent, in contrast to the temporary nature of the movement pertaining properly to the fairy tale. The fairy tale, at this stage of the adventure, has not yet materialized, since what was a mythical tale has become a legendary one. The two dimensions have not yet met: Étaín interacts with the Milesian characters as their fellow-creature and not in her original nature.

Midir, after a long search within his own plane, manages to find his love beyond it. Although presenting himself in a false appearance, in the instant that he appears before Étaín he makes the first escape of the tale insofar as he, a character pertaining to the indefinite, annuls the semantic as well as physical distance between his own dimension and that parallel to it. He finds himself in “a house outside of Tara,”10 which is a space pertaining to the definite plane, in which Étaín is to be found. Thus, he must be considered precisely as an invasion, at the moment in which he breaks down the barriers that separate the definite from the intermediate area between the two dimensions. His invasion manifests itself as an apparition, in the sense that we do not follow the journey through which he makes his movement: indeed, it is fair to say that the invasion of the fairies and of all the other characters of the indefinite manifests itself constantly under the form of apparitions, in that the point of view of the tale is normally oriented toward those characters belonging to the definite. Leaving his own dimension and entering that of Étaín, Midir has finally given form to the fairy tale and, at the same time, established a second fundamental function, which I will call MOVENS, if I may be permitted the Latin license. The term is not intended so much as it is currently accepted as being linked to the concept of causality—which nevertheless is present, in a modality dealt with later—but rather in its reference to the idea of movement. This function, of putting a character from one plane into contact with that of another, whether through escape or invasion, is the first step toward what we may define as the movement of the fairy tale. In the case in hand, as will be seen in the following scheme, one is dealing with an ascending movens, in the sense that it passes from the lower level of the indefinite to the higher level of the definite, in which the higher and the lower levels are spatial simulations of concepts connected to the notions of the definite and the indefinite discussed in the previous chapter.

The movens is followed by the third fundamental function, which is central in every sense. During all the time that Midir and Étaín are in conversation, and hence in the course of the relationship that temporarily links the two figures from two different dimensions, there takes place what I will call INTERACTION. Here, the term refers to an action taking place between at least two characters who are naturally different and interacting. For as long as this function lasts, the fairy tale holds in check the normal order, preestablished and foreseen, of the initial stasis, in order to substitute an abnormal intersection between two logically separate dimensions. Moreover, in the course of the interaction, the plane of origin of the character who has made the escape and/or invasion disappears from the horizon of the narration. For those who listen to or read the priomscel, the mythical plane is represented by Midir and no one else. When he is with Étaín on the legendary plane, Myth no longer exists since it has flown into Legend, thus recreating a condition of primordial unity. In the reconstruction of this unity, which is at once spatial, temporal, and between narrative contexts, the fairy tale reveals its principal value.

This reconstruction is momentary, however, ending at the moment that Midir must leave Étaín to return to his own plane. His return manifests itself, in analogy with his coming, as a disappearance, to the extent that we are ignorant of the route he takes to return to his own world. Strictly speaking, indeed, it is not even possible to state with certainty that Midir has returned into his own world, since in his capacity to become invisible, a characteristic trait of the Tuatha Dé Danann withdrawn into Fairyland, he could remain among men without being perceived. Equally, when he appeared, it was impossible to discern whether he had reached the higher world or whether he had already for some time been in a state of invisibility. One can say that, as far as the tale is concerned, what counts is what appears in an evident manner, what may concretely be narrated, and that the invisible presence of figures from the Otherworld should be considered simply as a potential source of the fairy tale. In any case, the disappearance of Midir should be interpreted as a return into his dimension of origin, and the function connected to this return we will call REDIENS, a Latinate label that evidences the semantic contrast between this function and the movens. Whereas with one the idea of movement in one direction was expressed, the other indicates an idea of movement in the opposite direction, or rather a return that annuls the preceding movement, precisely rediens. Hence, whereas the movens was ascending, the rediens is descending.

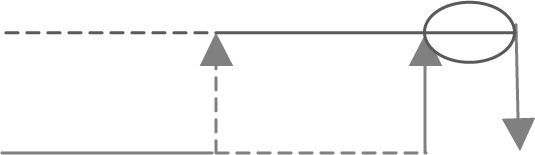

At this point, the graphic design can be enriched by three fundamental functions representing the movement of the fairy tale, which inserts itself into the preceding initial stasis (figure 5.3):

Figure 5.3.

The oval marking the interaction represents its nature as an invasion into a closed space, whereas an escape would have been portrayed by two separate curved lines to indicate the intermediate open space of the fairy tale. The rising and falling solid arrows represent, respectively, the movens and the rediens, which, lacking temporal consistency, insofar as they manifest themselves as an appearance or a disappearance, are perpendicular to the two dimensions of the tale. These do not develop horizontally, as does the interaction, which has temporal duration and a space in which to operate. In this regard, it should be underlined that the graphic makes it possible to follow the fairy tale in a diachronic sense, or rather in the succession of events that take place in the tale, and in a synchronic sense, in that it takes into account the contemporary coexistence of two separate contexts, which for the narration is impossible. The movens and rediens of Midir have only spatial consistency, deriving from the distance that separates the two planes of the tale. As soon as the distance is annulled, as can be seen in the figure, a void is created in correspondence to the mythical dimension, since for the entire duration of the interaction, it has flowed into the legendary dimension.

The movement ends after the rediens. Following it, a new static situation is installed that individuates the fifth fundamental function of the fairy tale or, in symmetrical opposition to the first, the FINAL STASIS, which recomposes the order preceding the movement but on different bases and according to the more or less clear changes caused by the interaction that has just taken place. With the final stasis ends the parabola of the fairy tale, and it is as if the datum of historia, suspended for the entire duration of the movement, prevails again over the fabula.

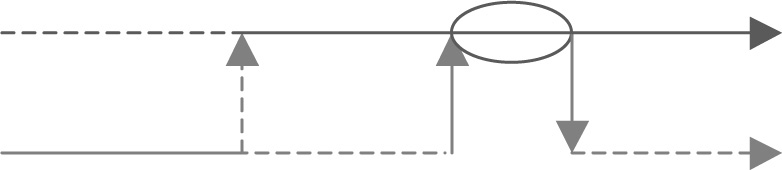

But the priomscel does not betray its importance as the complete model of the fairy tale and, as such, does not end after a single movement, but proposes another three, which are formed differently from the first. Hence, what takes place after the departure of Midir is not yet the final stasis, but simply the installment of a provisional order, in which one can recognize the existence of a sixth function, which we shall call the INTERMEDIATE STASIS, a function to be found naturally only in those tales composed of more than one movement. This provisional order instigates a situation of, so to speak, precarious equilibrium, since it is destined ultimately to be disturbed. Thus, this function, although static in concept, reveals itself to be in fact dynamic, manifesting through this the premise for a new movement. Hence, figure 5.4 has still only partial validity:

Figure 5.4.

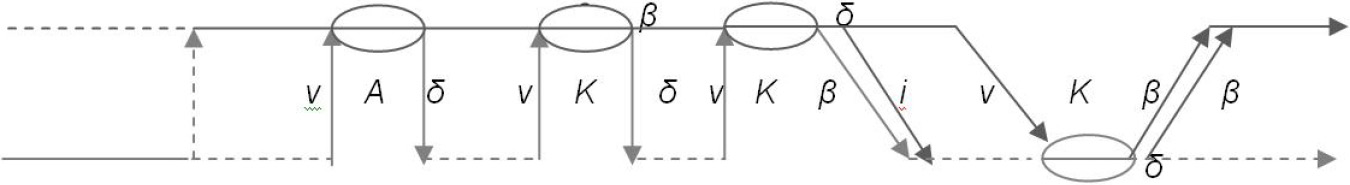

We know that Midir makes another two invasions, the second of which interests us most from a structural point of view. Although the movens remains the same, the rediens differs in two aspects. On the one hand, one notices the temporal consistency which, this time, a rediens linked to a figure from the indefinite assumes, since the escape of Midir and Étaín under the form of a flight of swans is observed by Eochaid and his men. On the other hand, it is seen how what is a rediens for Midir corresponds to a movens for Étaín, or rather the escape of a human figure from its own world to another world to which it no longer pertains. In this case, the graphic first represents the rediens with an oblique vector that conveys its diachronic significance; second, it flanks it with a parallel to indicate Étaín’s movens. This latter circumstance introduces a possibility that is to be found in other fairy tales—that is, the superimposition of rediens and movens, which in itself renders a further movement predictable, as long as the character connected to the movens is not assimilated.

The rest of the tale demonstrates just how Eochaid in turn escapes his own dimension to go and combat his enemy in his. Hence, we witness for the first time an invasion of the definite into the indefinite, ending only when the sovereign manages to recover his bride. This time, the graphic will display a descending movens and an ascending rediens, the second of which will be double insofar as it coincides with the rediens of Étaín. Moreover, both functions, as is normal in the case of actions performed by human figures, will have temporal consistency, so that they will be indicated by oblique vectors. Naturally, in the course of the prolonged interaction in Fairyland, a void will exist on the legendary plane, since it will have temporarily flown into the mythical one, indicating the recomposition of a unity, this time in the lower world.

With the return of Eochaid and Étaín into their dimension of origin after an assimilation and four movements, the tale ends with the definitive restoration—at least as regards the priomscel—of the initial equilibrium, albeit under a new light. Thus, the fifth fundamental function manifests itself, or rather the final stasis. At this point, it is possible to represent graphically in figure 5.5 the entire structure of the original fairy tale, through which we can discern the whole corpus of fundamental functions that create and compose all the traditional exemplars deriving from it:

Figure 5.5.

The choice of representing the final stasis through two vectors indicating continuity rather than the closure of the single fairy tale is connected to the idea of preserving the open nature of a tale that is strictly linked to the whole successive tradition, which it resumes directly. There is also the need to demonstrate how the single fairy tale does not exhaust the dialectic between two or more dimensions—in this case Myth-Legend—which is instead always susceptible to being reproposed, perhaps through the uses of the same characters as in the tale. Only in the case of a tale that contains the definitive disappearance of a character who alone represents a dimension—perhaps because he has been assimilated—would the corresponding line be interrupted, indicating that, at least in that tale, it no longer has any reason to exist.

Through the recognition of the ordered succession of the five (or six) functions identified up to now, it is possible to recognize the fairy tale itself, which avails of this basic structure to appropriate and act upon a traditional context that in itself would remain inert. One is dealing with functions and not simply with phases into which the tale can be divided. This occurs because, if it is truly possible to split up the tale into macro-sequences,11 it is even truer that their value descends primarily from the functionality inherent to the tale, so that it evolves according to the rules of the fairy tale and in no other way. Basically, it is the same situation that one encounters in Propp’s apparatus of the functions of the characters.12 Moreover, as the specific cases will display, the functions do not necessarily enter, all together, into the horizon of a concrete narration. A storyteller who omits the initial stasis to pass immediately to the fairy movement, or who skips from the interaction immediately to the final stasis, furnishes an incomplete tale, but the basis on which this is founded is not implicitly disputed: it represents the necessary postulate for the composition of any fairy tale, but also for the comprehension of its real range. In consideration of this, the fundamental structure shown in figure 5.6 emerges:

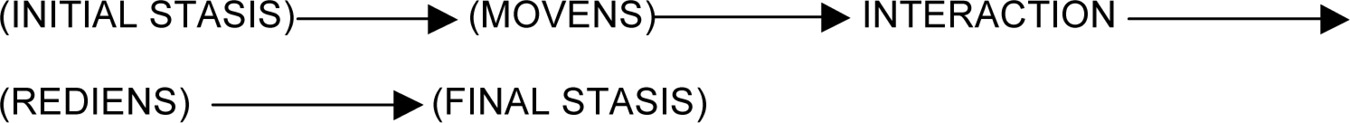

Figure 5.6.

From this scheme, on the one hand, is evinced the ordered sequence of functions through which each fairy tale is constructed, and on the other, the fact that the narration can allow the omission of each of the functions in parenthesis (the intermediate stasis can be considered in the same terms when the tale is composed of more than one movement). It is, however, absolutely incapable of tolerating the concealment of the interaction, insofar as this is the cardinal function around which the very sense of the fairy tale rotates. It can be considered as such because it contemplates the interaction between two dimensions of reality. Thus, the ideal, complete fairy tale—to which the priomscel comes close—presents all the functions explicitly although, following the tradition, multiple factors lead often to incomplete realizations of the model. The tale can be recomposed in its entirety during the writing phase, which in its nature is much more predisposed to completion and to the respect of an order than the oral tradition could ever be, since oral transmission often contains omissions connected to the mutability of the occasion and the inevitable blank spots deriving from the memory loss of the single narrator. Writing avails of an ease of composition not conceded to an oral narration that must take place within a limited arc of time. Of importance, the mnemonic process at the basis of orality can be facilitated by the adoption, perhaps unconscious, of a functional model such as that proposed here.13 In any case, it is undeniable that the particular conformation through which the structure of the fairy tale manifests itself in the single narration is a significant test for determining the oral or written origin of text and in determining those traits of orality and those of written elaboration in texts presented in both modes. This takes on notable importance in the transcription of traditional tales. In this field, the outcome of the encounter or clash between the two fundamental modalities of narrative transmission is always unpredictable. A structure recognized as a common model of reference certainly favors a less traumatic convergence.

Classification of the Functions and Characterization of the Fairy Tale

Finding it necessary to frame in a more general scheme the problematic treated until now, it seems legitimate to me to sustain the dialectic identified regarding the functions of the fairy tale, founded on the interpenetration among three orders of fundamental factors. The first is a constant, represented by a space–time organization, in itself immobile (at least on the synchronic plane), modeled on the planes of reality imposed on the basis of a narrative-historical evolution. The second is variable, made up of characters intended to represent the relative plane of pertinence and to give body, through their mobility, to the narrative dynamic. The third factor, the movement, is a sort of connective between the former ones, which, through the three dynamic functions of movens, interaction, and rediens, permits the convergence, on a single plane, of contexts that would otherwise remain separate.14 From a diachronic point of view, as has already been clarified, the multidimensionality of the real has not always had the same configuration. On the other hand, the characters, who theoretically are infinitely variable, reveal a functional constant that depersonalizes them and renders them merely representative of a certain time–space order. Constancy and variability are therefore concepts that can intersect, albeit within the limits of a well-determined narrative logic. Analogously, in the study of the notion of movement, or rather in the succession movens-interaction-rediens it is possible to find partial traits that permit a more complete approach to what still remains the constant factor through which the dynamic of the fairy tale unfolds. With this, I wish to underline that by conducting a deeper examination of the three aforementioned functions as they manifest themselves in the narrative tradition, it is possible to group them into an elementary classification, one which, on the one hand, would allow for a more specific characterization of the fairy tale in general, and on the other, would allow a more effective qualitative distinction between single examples of the fairy tale.

If we take into consideration the system of the thirty-one functions of the characters developed by Propp, we cannot fail to notice the evident qualitative characterization of large numbers of them.15 For example, the cardinal function, A, or rather the damage caused to a member of the family, implies a conflictual relationship between two or more characters, an opposition. The same could be said of the pair of functions, Q–M, or the struggle of the hero with his antagonist and his eventual victory. Moreover, the function of the donor, D, implies a wide range of solutions, from which in substance one can identify a friendly or hostile attitude of the donor toward the hero. On the one hand, therefore, Propp defines the functions not only on a strictly structural plane but also on a more widely qualitative one; on the other, he recognizes how the same function can manifest itself according to contrasting modalities.

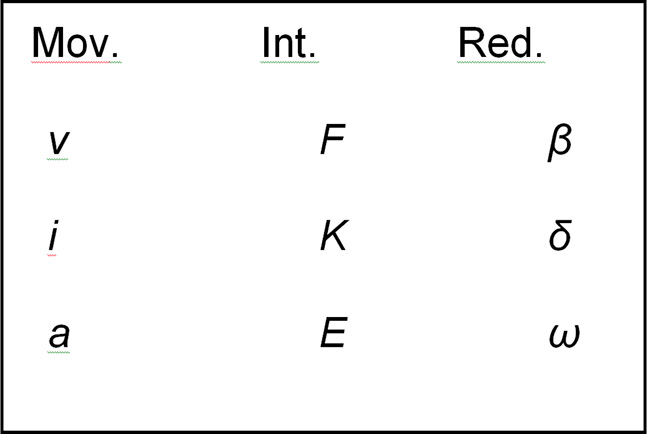

In the same manner, one can proceed with the three functions of movement identified up to now. (I exclude the functions of stasis both because they already belong to a specific dimension and because, since a logical continuity exists between the initial stasis and the movens and between the rediens and the final stasis, the categories adopted for the two dynamic functions would necessarily reflect on the other two, offering a sufficiently clear picture of the fairy tale in its entirety.) Thus, to obtain an exhaustive understanding of the fairy tale, it is vital to apply logical categories that are able to cast light on the distinctive characters through which the dynamic functions make themselves explicit. These categories, on the basis of an attentive analysis of the material at our disposal, can easily be reduced to nine, three for each function.

For the movens, the function which sets off the movement and which, therefore, must in some way furnish an explanation of it that is linked naturally to the background provided by the initial stasis, a classification on the basis of a principle of causality seems to me correct. The three fundamental causals can be individuated in the following categories:

voluntary (symbol v), which implies a clear and free intention of the character to escape from his own dimension and/or to invade another;

imperative (symbol i), which implies the imposition of the escape and/or invasion on the character by another character or a given circumstance;

accidental (symbol a), which implies the unawareness and/or involuntariness of a character in escaping from his own dimension and/or invading another.

The interaction, being the function through which a temporary fusion between two or more dimensions is established should, in my opinion, be classified according to a relational principle. Three fundamental relations can be identified as:

friendly (symbol F), in which definite and indefinite meet on a plane of concordance and/or complicity, so that a synthesis between opposites is realized;

conflictual (symbol K), in which definite and indefinite meet on a plane of discordance and/or diffidence, so that an antithesis between opposites confirms itself;

external (symbol E), in which the relationship between definite and indefinite limits itself to a simple coming to awareness (reciprocal or not) of the other’s existence, so that there exists a certain distance between opposites.

Finally, the rediens, being the function which brings the movement to an end, and that hence bears its consequences, which reverberate in the final stasis, should be classified according to a principle of consequentiality. In this case, three fundamental resultants can be identified:

beneficial (symbol β), in which definite and/or indefinite show an improvement of the initial condition from the interaction or avoid a deterioration;

damaging (symbol δ), in which definite and/or indefinite show a deterioration of the initial condition from the interaction or lack an improvement;

none (symbol ω), in which definite and/or indefinite emerge from the interaction with no change in their initial condition, either better or worse.

Regarding the rediens, it should be noted that, since it follows an interaction, it implies in turn a double interpretation and hence a double resultant, one for the definite and one for the indefinite, particularly when it follows a conflictual interaction in which one character draws an advantage and one is damaged. However, to preserve a correspondence with the movens, it is the resultant pertinent to the character and to the dimension responsible for the movement that counts the most; thus, if it is not strictly necessary, the indication of the other can be avoided.

Applying the above categories (with the help of their corresponding symbols) to the model already delineated and graphically illustrated, one can complete the determination of the purely dynamic development of the fairy tale. This is now identifiable as the deep level of its structure, while we also recognize a modal or descriptive development,16 assimilable to a sort of surface level, which is the practical manifestation of the structure. This implies above all the characterization of the approach that the specific characters in the tale have with the context of the fairy tale. Thus, the nature of the movens can reveal the level of consciousness that the definite has of the existence of the indefinite or vice versa; the modality of the interaction can tell us what is the effective gap, in the widest sense of the term, between one dimension and another; and the genre of the rediens, finally, can display what palpable value is attributed to an experience undergone beyond the canons of daily life. The status of the character alters then with the alteration of the categories that define both his or her being and actions within the tale. Hence, if the nine categories are inserted into a table, it will be possible each time to identify the path taken by a character in the realization of his movement and, consequently, his typology. One could also individuate the subgenres incorporated within the wide range of the fairy tale (see figure 5.7).

Figure 5.7.

If, for example, we were to isolate the sequence v–K–β, referring to a definite character, we would have identified, on the one hand, the classical typology of the hero and, on the other, would have evinced the development most typical of the tale of magic studied by Propp, which would demonstrate only one of the possible narrative developments of the fairy tale. In fact, by simply substituting β with δ, we would have a sort of antihero and hence the form of the antifable, in which the canonical victory of the protagonist is supplanted by his defeat. Or, by isolating the sequence a–E–ω, we would have individuated a sort of hero by chance, who undergoes the experience of the legend as traditionally understood—the supernatural vision—from which he draws nothing other than the discovery of another dimension. The fairy tale envisions potentially all the sequences in the table and in this demonstrates its value as a transversal category.

But to observe concretely how this system of categories is applied to the fairy tale, one must return to the priomscel, or rather to the graphic scheme illustrating its structure (figure 5.8):

Figure 5.8.

This can be considered the complete representation of the structure of the fairy tale, which takes the form primarily of a multiple succession of stases and movements. As well, it correspondingly individuates specific triadic sequences that mark each of the key moments of the tale. The sequences expand when they imply a double resultant, fruit of a conflictual interaction that has provoked consequences in both of the dimensions involved, or when two functions manifest themselves contemporaneously, a rediens and a movens, as when Midir escapes with Étaín, or two rediens, as when Eochaid brings Étaín back to his world.

But these, like the other innumerable, unobservable forms in the priomscel, denote the natural variations on theme of a genre that, in the great liberty allowed to individual elaboration, remains nonetheless firmly anchored in its fundamental structure. This structure can be found in the entire narrative tradition that Yeats gathered in an exemplary collection and that Stephens reworked according to personal canons of poetics.

Notes

1. Cf. Propp, Morphology of the Folktale, 20–21: “Running ahead, one may say that the number of functions is extremely small, whereas the number of personages is extremely large. This explains the two-fold quality of a tale: its amazing multiformity, picturesqueness, and color, and on the other hand, its no less striking uniformity, its repetition.”

2. Lotman, The Structure of the Artistic Text, 217.

3. Ibid., 220 (my italics).

4. See ibid., 209.

5. See Rolleston, Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race, 164: “To this great story the tale of Etain and Midir may be regarded as what the Irish called a Priomscel, ‘introductory tale’, showing the more remote origin of the events related.”

6. See ibid., 155–63.

7. Cf. Northrop Frye, “The Mythical Approach to Creation,” in Myth and Metaphor: Selected Essays 1974–1988, by Northrop Frye (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1991), 241: “Creation myth is in a sense the only myth we need, all the other myths being implied in it.”

8. Cf. Algirdas J. Greimas, On Meaning (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), when he occupies himself with identifying the Elements of a Narrative Grammar; in particular, he states that narrative grammar is made up of an elementary morphology, which is furnished by the taxonomical model, and by a fundamental syntax, which operates on the previously inter-definite taxonomical terms.

9. The implicit meaning of the expression initial stasis can be compared to the notion of introduction adopted by Labov and Waletsky and to that of setting used by van Dijk and Kintsch. In both cases, one is dealing with the reconstruction of the tale into five micro-categories, similar to the theoretical proposal put forward in the present chapter. But, apart from the introductive categories, the system is oriented in a totally different way. As seen further on, the final stasis, for example, which closes the narration, has little in common with Labov and Waletsky’s coda and with the moral of van Dijk and Kintsch: see Mihály Hoppál, “Narration and Memory,” Fabula 22 (1981): 286–89.

10. Rolleston, Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race, 159.

11. Cf. Hoppál, Narration and Memory, in particular 284–86.

12. Indeed, he declares that the functions “constitute the fundamental components of a tale” (Propp, Morphology of the Folktale, 21).

13. Cf. Hoppál, Narration and Memory, 281: “From the recalled propositions, and by the help of the narrative and of linguistic formation rules, a given narrative text could be retold by the narrator again and again with relatively slight or minor modifications” (my italics).

14. Lotman is moving in the same direction when, by plot “means an eventful action sequence with three components:

- some semantic field divided into two mutually complementary subsets;

- the border between these subsets, which under normal circumstances is impenetrable, though in a given instance (a text with a plot always deals with a given instance) it proves to be penetrable for the hero-agent;

- the hero-agent” (Lotman, The Structure of the Artistic Text, 240).

15. See Propp, Morphology of the Folktale, 25–65.

16. Cf. Greimas, On Meaning, in which the French scholar distinguishes a simple narrative utterance from modal and descriptive utterances.