7

The Significance of the Fairy Tale in Historical and Cultural Contexts

An Indicative Metaphor

The Celtic Twilight can be considered the work with which Yeats ends his exploration of the world of the folkloric fairy tale. In this work, according to an entirely interior logic, more or less brief essays alternate. This presentation should be understood as reflecting themes held dear by the author (more often than not inspired by first-person experience) and tales drawn directly from the popular voice, at least as declared by the writer. The text in question is, in fact, an autobiographical account of a series of journeys made by the author to the west of Ireland, in particular to the area of Sligo, where he found his family roots. It is a sort of catabasis into a reality that preserved its links with the world depicted by the fairy tales previously collected in written sources. We face an attempt to acquire in a deeper, more personal way the values on which a new poetic was being built, to approach directly the context from which the primigenial energy needed to renew literature came and also to widen the common rational perception of reality that was being unleashed.1 In substance, this return to the places of the author’s childhood translates itself into an analogous regress into an aboriginal dimension, the unitary dimension of the universe in the mythical phase. According to the orientation of Yeats, this dimension can be both recreated and relived by means of the patrimony of fairy tales offered to the poet by the voice of those peasants who, thanks to the uninterrupted activity of storytelling over centuries, preserved their links with a past otherwise destined to oblivion. The loss of these tales would have deprived the contemporary age of a traditional heredity made all the more precious by the awareness of its function as an irreplaceable instrument with which mankind in general, and the poet in particular, can go beyond mere “knowledge” and reach authentic “wisdom.”2

This last observation opens the way to the type of analysis to be conducted here, whose objective is to identify those characteristics of the fairy tale that can be conveyed by the term significance, or rather its capacity to carry one or more fundamental meanings. As mentioned in the previous chapter, this is essential to verifying the universal importance of a narrative genre which, from the point of view of our research here, takes in an extremely wide semantic spectrum. An article that appeared in the Irish University Review is very interesting in this respect.3 It puts forward a convincing hypothesis, aimed at unveiling the underlying unity of The Celtic Twilight that given its (permit me the license) Menippean nature seems rather to subtract itself from any coherent identification. This hypothesis is based on a careful analysis of the text, from which emerge a body of recurring elements that, whereas on the one hand, they recompose in an organic whole an extremely heterogeneous text, on the other, reveal a significant expression of the message conveyed by the fairy tale, particularly from the point of view of an artist who approaches it with the greatest of expectations. Whereas the three key elements identified by Kinahan are intended to connect the apparently disconnected threads of The Celtic Twilight, they can also be read as the fundamental supports on which to model the principal dialectic of the fairy tale, that which opposes and composes the already examined concepts of stasis and movement.

According to Kinahan, The Celtic Twilight is founded on the assumption that the sensible world is manifestation of “a fall from grace,” after which man has been trapped “in the web of mortal limitations.”4 The term web (as net and the more complex cobweb veil5), which Yeats uses in the work, is the preliminary element for an interpretation of the sense of the fairy tale, the metaphor through which to interpret the state that the tale, and hence mankind, have to face. This, as we know, follows a primitive situation of grace, in which the concept of a limit has no reason to exist. However, man and his world are not wrapped in a continuous cobweb, because here and there are gaps through which it is possible to open up to a wider dimension. In the moment that the “myths of fall are also as a rule myths of regeneration,” then the “images of entrapment give way to images of openness, and most specifically to images of doors, thresholds, gates and gateways, ways out.”6 By adopting these terms, Yeats draws the reader’s attention to the existence of a threshold, an opening that can put man in contact with a world lying beyond the confines of daily life, an element that, from the point of view of the fairy tale, implies the potentiality of a passage from one dimension to another, but which also implies the ability to recognize, albeit under a false appearance, one of the openings to the Otherworld. In the text, one reads of the authentic supernatural experiences undergone by Yeats and by people whom he has met, but these are absolutely rare and destined to the privileged few. Moreover, they are concentrated in that corner of Ireland in which modern civilization has only partly corrupted the ancestral Celtic heredity. The element that permits a much wider public to pass the threshold—albeit not in the first person—is identified in the third cardinal figure of The Celtic Twilight, the storyteller, who, in Homer and in more or less historical Irish narrators, is celebrated by Yeats as the one who through the force of words can stem the flow of time. In The Celtic Twilight, and in the fairy tale in general, there is a rejection of the chronological conception of time, to the extent that in both the narrator lends his voice to something immortal.7

A similar reading of Yeats’ work offers a vision of the world in which a given situation that presents an absolutely partial image of reality is set in opposition to the ability to transcend this situation, both on the real level (perhaps through a journey to those places in which this is most probable) and on the imaginary level, using the means provided by the storyteller. The storyteller reveals himself to be a sort of privileged interpreter who, with his gifts as an affabulator, is able to put into contact two coexisting but distant planes of reality. He puts into action what, from the viewpoint of the Weltanschauung of the fairy tale, is a constant potentiality. We can recognize the intersection between the definite and the indefinite dimensions only when this is made explicit by the tale, which has a reason to exist only in virtue of the fact that an opening has been made in the web that, due to a historically imposed norm, limits human perception. It is not enough that a human being should meet a fairy to have a fairy tale. It is necessary that the former is in a condition to be aware of his interaction with a figure from the indefinite, or that the latter should be willing to show himself. In Yeats’ A Donegal Fairy,8 we find ourselves in an ordinary house, in which an ordinary woman is cooking. The story could continue on this everyday level, if it were not that an unexpected event takes place: a fairy falls accidentally into a boiling pot. If this incident had not taken place (a rare example of an accidental movens connected to an indefinite character), the woman would never have noticed all the fairies who immediately rush to the assistance of their companion (in this case, the movens is voluntary). Without an unexpected event, the woman would have remained completely ignorant of the fact that she cohabits with representatives of the indefinite, and consequently, despite having the potentiality, could never have narrated the fairy tale which finds itself among the pages of Yeats’ collection.

In light of this example from the text, one can understand better the antithetical pair of attributes with which the planes of the definite and the indefinite have previously been identified. The human character, as part of an objective daily reality, has no more than limited awareness of what surrounds him. He is not able to grasp the reality of something discussed simply on the level of the subjective experience of someone else. The existence of an invisible microcosm within the visible world escapes his purely terrestrial sight. Figures from the fairy world form part of a past that, until they manifest both their presence and prerogatives, cannot disturb the present equilibrium. In short, there is an entire group of elements and phenomena that lie hidden beneath a veil, at least until this veil is removed. The fairy tale, through one or more heroes, raises this veil and, by means of its diffusion among an ever-widening public, renders always less subjective the knowledge of the existence of a world that may have been considered well canceled by the inexorability of progress. The woman who had the chance to observe the fairies in her own home had probably already heard tell of these beings, so that her adventure provides further testimony of the consistency of what collective tradition had already handed down. As soon as his adventure is turned into a tale, the latter becomes an involucre, through which deeper awareness of reality manifests itself and is offered to a more or less extended community. No less than a rite, the fairy tale permits the shift of a latent mythical aspect into a conscious historical context.9

The Epihanic and Pragmatic Components of the Fairy Tale

What arises at this point is the epiphanic aspect of the fairy tale, its capacity to reveal reality under a particular light, to display its darker side, placing man face to face with all that is other than himself. Dealing with the epiphanic significance of the tale implies also paying attention to the other fundamental aspect, the pragmatic, which corresponds in practice to the spatial and temporal sequence identified in the structure of the fairy tale. The characters move against a determinate paradigmatic horizon with the double objective of performing an action that alters, in a more or less obvious way, an initial situation, and coming to consciousness of something that, before the action began, was either partially or completely unknown.

On an elementary level, the two components are strictly linked in that there can be no epiphany without at least the pragmatic action of a character. Likewise, it is impossible to conceive of any action without a conceptual horizon within which to identify the context and the characters who must act. It should be noted, however, that it is unlikely that, in every tale, both sides of the coin will have the same importance. From time to time, one will be predominant over the other, to the extent that, in some cases, one will almost seem to disappear because of the exuberance of the other.

Returning for a moment to what was said in chapter 5 regarding the triadic sequences identifiable through the application of the nine qualifying categories adopted for the classification of the dynamic functions: in the presence of a tale characterized by the scheme v–K–β, one can intuit the preponderance of the pragmatic category, since the attention of the narrator is naturally directed toward the actions of the hero, and we are little interested in ascertaining, for example, the nature of the supernatural being in the role of antagonist. On the other hand, a narration that develops on the scheme a–E–ω is decidedly oriented toward the discovery of a given indefinite phenomenon and takes little interest in how the hero has arrived at the place of the meeting.

Let us return, finally, to the classical opposition between Märchen and Sage, between the tale of magic identified by Propp and the legend as it was conceived by Lüthi, an opposition that finds its raison d’etre in a large part of the European tradition. In this tradition, the fairy tale tends easily to divide, creating almost a rift between tales oriented toward the pragmatic datum and others oriented toward the epiphanic datum. In the Irish context, the situation assumes far more subtle contours. In Yeats’ collection, we practically never encounter the narration of the feats of heroes entirely detached from a living context,10 just as one always notices an unparalleled interest in providing a clear and serious identity for figures and phenomena pertaining to an indefinite plane. If anything, one can see in the Irish tradition a greater predisposition toward the epiphanic aspect, a tendency in which, as can easily be intuited from what has been said up to now, an innate component of the Irish spirit is reflected, a never-satisfied attraction to everything belonging to an otherworldly dimension.11

If one compares Yeats’ text The Man Who Never Knew Fear12 with variants of the same fairy tale collected by the Grimm brothers13 and Afanas’ev,14 one notes how, despite the fact that they all develop on the same structure, which varies substantially only in the number of escapes that the hero makes in search of fear (it should also be underlined that the Irish version contains the greatest number of movements, in confirmation of the fact that the importance of the epiphanic datum in no way overshadows the pragmatic potentiality intrinsic to the fairy tale), the approach toward the figures from the indefinite is decidedly different. On the part of heroes from German and Russian variants, figures of the indefinite are considered no more than bench tests on which to exercise one’s courage, without the slightest attention paid to their identity by the hero. Thus, the effort of the struggle is not indeed noticed.15 In the Irish variant, the hero performs his feats with a fair dose of respect for something that goes beyond his understanding. Whereas the German and Russian heroes act pragmatically, in their own interest, the Irish hero not only acts for the common good, but also takes on the responsibility of revealing to the community the nature of events that, prior to his arrival, were wrapped in the deepest mystery. Finally, the German and Russian heroes learn the meaning of fear, but this takes place in a humorous key, linked to events that are obviously natural (it is enough to surprise them in their sleep with a chest full of darting fish). The Irish figure, however, remains a spotless and fearless hero, because, I would suggest, of the correct relationship he has established with the indefinite dimension, which had been a source of fear for the rest of the community. Whereas the tales of the Grimm brothers and Afanas’ev concentrate exclusively on the more or less heroic feats that lead the characters to easy rewards, Yeats’ tale seems to want to exalt the feats of the hero (who still is given the reward that he deserves), but with the objective of instituting a new universal order, in which the definite and the indefinite, reciprocally revealed, can coexist peacefully.16

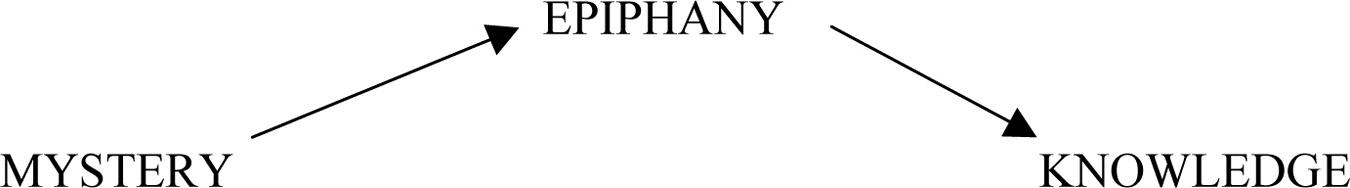

If, on the one hand, the movement of the fairy tale is finalized in a transition from a phase of mystery to one of consciousness through the cardinal passage of epiphany, on the other, it is the factor of disturbance that conducts an initial situation of equilibrium to a final situation in which this equilibrium has been modified. Both aspects shape themselves perfectly on the structural model of the fairy tale, so that the epiphanic process can be depicted in the following graphic guise (see figure 7.1):

Figure 7.1.

Simply changing the terms, the pragmatic process can be illustrated as in figure 7.2:

Figure 7.2.

In both illustrations, I have attempted to employ terms that give the clearest idea possible of the fundamental processes that the fairy tale brings into being. However, if instead of the two triads adopted I had limited myself to reproposing the structural triad initial stasis–interaction–final stasis (the arrows conserving the functions of the movens and rediens, respectively), I think the nature of the two processes identifying the conceptual dynamic of the fairy tale would have been equally clear. In both cases, of decisive importance is the movement that leads one or more characters from one dimension to another, following which the event takes place that, in one way or another, modifies the initial situation imposed by the contest. What varies is the function of the hero who, on the epiphanic plane, is first simple representative of his dimension, then the witness of another dimension, finally assuming the function of divulger of what he has discovered. On the pragmatic plane, whereas at the beginning the hero was quiescent, in syntony with the calm of the contest to which he pertains, in the course of the interaction he is transformed into an active hero, to return, after his escape and/or invasion, to quiescent again; but this only occurs after having changed, for good or evil, his and/or others initial state.

Allowing that no strict correlation exists, it is fair to state that when the interaction is external, one presumes that the story is oriented toward the epiphanic aspect (for example, Connor Crowe in Flory Cantillon’s Funeral17 remains hidden and at a distance on purpose, in order to discover the secret of the burial that the merrows offer to members of the Cantillon family). Here, a conflictual interaction (one should consider that the term confrontation is used to indicate the central phase of the pragmatic process; the more explicit contest could have been used) individuates logically a story oriented toward the pragmatic aspect (for example, the vicissitudes undergone by Daniel O’Rourke in the story of the same name,18 on account of the hostility of a pooka). The friendly interaction seems to be the most neutral, at one moment limiting itself to a simple dialogue between characters pertaining to different dimensions (as happens in Rent-Day,19 where the interest of the story is focused on the meeting between the poor Bill Doody and the legendary figure of O’Donoghue, who permits his interlocutor to attend to his own state of poverty); whereas at the next, this involves far more lively action (as demonstrated by The Piper and the Púca,20 in which, after a ride on a pooka’s back, a human musician must play his bagpipes at the feast of the banshees, to then return home having been gifted with exceptional mastery of his instrument).

From all the examples given, one can see that, in each case, it is impossible to individuate an exclusive predilection of any fairy tale for one aspect or another. The tale is firmly rooted in a dialectic between the epiphanic and pragmatic lines that reflect the necessary interaction between the heredity of folklore and narrative structure, between traditional paradigm and syntagmatic elaboration, and between the functionality and availability of the story.21 It is significant that Yeats, having discovered in folklore an indispensable source of literary inspiration, aspired to creating himself, in the figure of Red Hanrahan,22 a character capable of passing from literature to folklore, according to the logic of the virtuous circle, for which literary writing and popular orality could set up a profitable relationship and create an ever more solid bond. Stephens himself, when he made his first literary approach to the stories in the Fenian Cycle, imposed limits on himself that kept him firmly within a traditional context.23

To the traditional context belongs the concept of deep structure, in which the formal identity of all fairy tales has been recognized. This also forms the matrix that can liberate the compositional freedom of the individual, which manifests itself instead in the surface structure. But to this context also pertain a certain imaginative store, the whole of figures and phenomena that a millennial tradition has sedimented in the popular mentality. Now, although the storyteller has an almost inexhaustible faculty for varying the plot of any fairy tale (and hence of intervening personally on the pragmatic aspect of the text), he is conceded far less liberty in approaching the imaginative store, on which the epiphanic character of the text is plainly based. In the preceding chapter, we saw how a narrative tradition can be born, or at least how this event is represented within the narration itself. We were faced with characters who, presumably for the first time, were put into contact with an indefinite dimension, from which they drew the fairy tale, which was handed down from then on. But did the trials they underwent (or simply narrated) have no link with similar or identical events registered previously? Yes and no. From a strictly narrative point of view, the experiences of Pat Diver and Michael Hart, insofar as they were individually conceived of and disclosed, are a point of departure, a unicum that opens up a new front within the tradition. But if one’s glance widens, it becomes clear that one is dealing once again with the theme of the meeting with a particular type of well-recognizable figure belonging to the indefinite. In this case, the figures are far darrig, who significantly occupy a section of Yeats’ collection. The two characters may be ignorant of these creatures belonging to the popular imagination, supposing their extremely hypothetical isolation from the community, but when their disclosures become traditional, they are absorbed into the wider horizon of folklore, in which they are reregistered simply as two new interpretations of a known phenomenon.

In practice, every new fairy tale is based on a preexisting imaginative store, which, consciously or unconsciously, has a determining influence on the characteristics attributed by the given storyteller to the figures, phenomena, or circumstances that distinguish his story. The preexisting character of what is narrated can be implicitly perceived from the exterior, as in the case of the stories of Pat Diver and Michael Hart, or be explicitly declared by the narrator himself. Consider, for example, how the storyteller of A Donegal Fairy begins his story: “Ay, it’s a bad thing to displeasure the gentry, sure enough—they can be unfriendly if they’re angered, an’ they can be the very best o’gude neighbours if they’re treated kindly.”24 Before narrating the supernatural encounter, the storyteller introduces the theme of the tale on the basis of the traditional image of the gentry—or rather, the fairies—as if in this image he seeks complicity with the interlocutor so as to justify his testimony. In The Soul Cages, it is instead the main character, Jack Dogherty, who complains of the fact that “though living in a place where the Merrows were as plenty as lobsters, he never could get a right view of one.”25 In this case, the character is aware a priori—an awareness deriving from the previous disclosures of his grandfather and father—of the existence of the merrows before actually meeting one of them.

However, one must also contemplate the possibility of encountering a fairy tale focused on the native imagination store, in no way linked to a preexisting tradition, but rather the first testimony in absolute of the existence of a determinate aspect of the indefinite. This is extremely improbable in the case of more recent stories, but going back in time becomes all the more plausible. One must return to the more or less historical moment in which a certain folklore tradition began. But, as can easily be intuited, it is very unlikely that the fairy tale has been conserved that, for example, speaks for the first time of the leprechaun or explains perhaps his link with the art of the cobbler. Faced by a tradition that, for centuries, has entrusted itself exclusively to orality, it is obvious that a continuous exchange occurs by which, as one proceeds, the most ancient examples of a certain type of fairy tale disappear to leave space for more recent interpretations. Only writing would be capable of putting us into contact with the native phase of a figure or phenomenon from the indefinite.

In any case, an example of this native imagination is to be found in Yeats’ collection, where the account is given of a twelfth-century writer, Giraldus Cambrensis, regarding the first appearance of a ghostly island, able to rise or sink at will, until the inhabitants of the region, by means of a flaming dart, manage to stabilize and colonize it.26 The storyteller in this case states clearly that he is able to explain the origin of the phenomenon, so that all the stories focused on ghostly islands (which from the twelfth century onward enrich the tradition) will have to be considered in one way or another indebted to the native testimony of Giraldus Cambrensis. The same could be said of any storyteller who, perhaps in far more recent times, was capable of creating a figure entirely independent of the tradition and to impose it in the popular imagination. Although this is plausible in the literary context, where the writer has a far wider margin of liberty, it is much more difficult in the field of folklore, where the traditional imagination exercises a force of attraction as efficacious as it is rooted in a past that—ultimately—always originates from a mythical dimension.

The Dialectic Between Signifier and Signified

As previously mentioned, each fairy tale, operating on a preexisting imaginative store, forms a sort of ulterior interpretation of a consolidated tradition. In substance, what presents itself to the popular memory is a more or less wide repertory of elements, each of which has given origin to determinate traditional thread. Each storyteller can choose into which thread to insert himself, with the intention of offering his personal contribution to the a posteriori transmission of a theme from folklore, reworked in determinate narrative structure. Thus, he will have once again erased the distance that separates a nonetheless indefinite phenomenon from definite context in continual change. He will have brought past and present onto the same plane, with the past becoming ever more distant with the passing of time. This necessitates a continual reinterpretation, to prevent the past from becoming simply a memory that ultimately disappears, thus leading to the vanishing of an entire traditional thread—an irretrievable loss both on the level of folklore and of narrative. The task taken by the fairy tale is, therefore, that of guaranteeing a certain consistency to events that, given their nature, tend to escape any attempt at coherent systematization. This occurs unless a writer such as Yeats intervenes, ordering the traditional patrimony according to a personal, but rational classification, or, on a higher level of elaboration, Stephens, who makes of the Fenian material a poetically ordered whole and further frames it between two metanarrative texts. But the main task of the fairy tale is, at the same time, that of keeping alive a narrative tradition in which Irish folklore has its principal resource.

Obviously, the tale cannot give any real consistency to material that, until proved to the contrary, is purely verbal. But, from the point of view of the characters who act in the story, this consistency is possible. Between the figures from the definite and those from the indefinite, a dialectic is set up that, in a certain way, reflects de Saussure’s distinction between signifier and signified, or the relationship between name and object. Thus, the fairy tale opens, more often than not, with an explicit awareness of elements that only later will be put to the test, but which at the level of the initial stasis can only be named or, at least, implied.

In the town where Jamie Freel lives “it was well known that fairy revels took place; but nobody had the courage to intrude on them”:27 everyone knows about the fairies, and everyone talks about them, but no one is willing to take the step that would annul the distance between the named and the object. If it were not for the hero, who eventually decides to go to the place where the fairies are said to live, the real meaning of the concept would remain unknown; it would be a void signifier. Only when Jamie Freel escapes from his dimension and invades the castle inhabited by the fairies is a conjunction made between the mere mental image evoked by a name and the effective consistency of the object so denominated, since, on his return home, the hero will be fully aware of the meaning intrinsic to the verbal involucre—fairies—and, albeit indirectly, he can involve other human beings. The clearest image of the direct experience of Jamie Freel will remain incontestable until an epigone emerges willing to follow in his steps and, in altered conditions, to join the name again to the object, to complete the signifier with its exact signified. As the tradition linked to that specific category of fairy goes on, each main character of the fairy tales will furnish to the community, depending on the case in hand, a reconfirmation or a redefinition of the images and conceptions inherited from the past, or perhaps a rediscovery of something that had been removed from popular memory.

From the viewpoint of the conscious appropriation of the meaning intrinsic in the indefinite, the figure of Tuan Mac Cairill, the main character of the story that opens Stephens’ collection,28 seems exemplary to me. In the adventures of this character, practically all the mythical, legendary, and historical events of Ireland are reproduced, up to the meeting with St. Finnian, who gathers his testimony. Tuan assists in the first person at all the successive invasions of the island and thus, in his eyes, all the figures and events that are to become part of the narrative tradition and enter into the popular imagination gain consistency. What permits him to live more than a thousand years is a progressive metamorphosis by which he first becomes a deer, then a boar, a hawk, and a salmon. He becomes a man again in the end, so that he can communicate his extraordinary experience to a representative of the definite. It does not seem casual to me that Stephens should begin his collection with such a story, since it is the most appropriate introduction to the themes that fill his pages. We could define it a sort of guiding fairy tale, in that any narrator can start from it in developing any fairy tale, or especially those focused on the relationship between Myth and Legend. But, above all, in this metamorphosing hero we discover the illustrious predecessor of all the heroes who will break down the barriers between those worlds which Tuan has seen born: his testimony is the unshakable guarantee for the entire edifice that supports the fairy tale. And Stephens is definitely conscious of this function.29

Characters such as Jamie Freel and Jack Dogherty represent better than any others the typically human desire to know and the necessity of knowing the reality that surrounds one.30 Undoubtedly, in such figures one cannot but notice the notable drive provided by the desire for adventure, as there is likewise a definite intention to procure a pleasant story to share with other people. But, in the depths of the fairy tale lies a fundamental tension aimed at unveiling the meaning of what exists beyond the veil of appearance and at shaking up the dust that time naturally accumulates on the data and values preserved by a relatively stable memory. In such an opening, in full relief, in my opinion, should be understood the peculiar, universal value that led writers such as Yeats and Stephens—so attentive to the epiphanic function of the literary text—to become involved actively in the virtuous circle of the fairy tale, a circle in which space exists for many other Irish writers, including the most illustrious of all—James Joyce. Besides, how could one discuss epiphany without invoking the name of Joyce? I hope to respond to this question in the next chapter, through the specific reading which I propose of Dubliners and, more generally, of the relationship between the fairy tale and the tale properly speaking, or again between the fairy tale and the pseudo-fairy tale. These are conceptually relevant pairs, capable of instituting a stimulating dialectic of narratological interest.

Notes

1. Cf. Rosita Copioli, introductory note to Il crepuscolo celtico, by William B. Yeats (Milano: Bompiani, 2001), 7–18. See in particular 15: “Yeats had turned to popular poetry as the first of the paths to consciousness. From the images and myths in which it abounds and which were so familiar to him, he must have understood that consciousness always proceeds through models and symbolic forms, not only in poetry, but also in science, philosophy and all disciplines.”

2. See Frank Kinahan, “Hour of Dawn: The Unity of Yeats’s ‘The Celtic Twilight’ (1893, 1902),” Irish University Review XIII, 2 (1982): 197.

3. See ibid., 189–205.

4. Ibid., 191 (my italics).

5. See ibid., 192.

6. Ibid., 193 (my italics).

7. See ibid.; cf. also Thuente, “Traditional Innovations,” 96–102, in which a spatial and temporal conception is given which Yeats drew directly from the oral and popular tradition.

8. See Yeats, Irish Fairy Tales, 47–48.

9. Cf. Dario Sabbatucci, Il mito, il rito e la storia (Roma: Bulzoni, 1978), in particular 340–44.

10. Cf. Nicolaisen, Concepts of Time and Space in Irish Folktales, 156: “The landscape of Irish folktales, whether in this world or the other, is—and this has to be said, although it may sound trivial—the landscape of Ireland. In particular, since protagonists have to leave home in order to complete their assigned tasks and ultimately to find themselves, it is the landscape of the roads of Ireland.”

11. Besides the attraction that the Irish feel for what lies beyond, one must also take into account the harmony that this people has reached in its relationship with supernatural beings. In this regard, Yeats draws attention to the fact that there is a notable difference of approach between the Irish and their Scottish cousins, dedicating to the theme a chapter in The Celtic Twilight (London: A. H. Bullen, 1902). See in particular 178–79: “You have burnt all the witches. In Ireland we have left them alone. . . . You have discovered the faeries to be pagan and wicked. You would like to have them all up before the magistrate. In Ireland warlike mortals have gone amongst them, and helped them in their battles, and they in turn have taught men great skill with herbs, and permitted some few to hear their tunes. . . . In Scotland you have denounced them from the pulpit. In Ireland they have been permitted by the priests to consult them on the state of their souls.” This last remark sanctions once again the peaceful interpenetration that, in Ireland more so than elsewhere, took place between the pagan heritage and the Christian faith.

12. See Yeats, Fairy and Folk Tales of Ireland, 344–51.

13. See Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, Grimm’s Fairy Tales (Teddington: Echo Library, 2006), 318–29: The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was.

14. See Aleksandr N. Afanas’ev, Russian Fairy Tales (New York: Pantheon, 1945), 325–27: The Man Who Did Not Know Fear.

15. One of the distinctive characteristics that, for Lüthi, distinguishes the Märchen from the Sage is precisely the effortless way in which the hero of the fairy tale performs his feats, where the main character of the Sage allows all the tension he undergoes in facing his adversary to be felt. Since in the story from Yeats in question the hero performs his feats in the style of a Märchen, but behaves like a character from a Sage, one is led to think that the distinction proposed by Lüthi is not so binding, or that the Irish story, taken altogether, is more easily inserted into the category of the fairy tale examined until now.

16. Obviously, it must be mentioned that, in the inclusion of one variant rather than another of the same narrative type, the criterion of selection employed by the editor is definitive. Hence, while it is plausible that Yeats would have consciously chosen the more serious variant because it was closer to his own poetic of the fairy tale, it is also fair to think that the Grimm brothers and Afanas‘ev, according to a different criterion, preferred to leave space for the humorous side of their narrative tradition.

17. See Yeats, Irish Fairy Tales, 80–83.

18. See ibid., 105–12.

19. See ibid., 216–19.

20. See ibid., 102–5.

21. Cf. Northrop Frye, “The Archetypes of Literature,” in Fables of Identity, (New York-London: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1963), in which the Canadian scholar sets up an interesting dialectic between narration and meaning on the basis of the literary phenomenon. Of particular interest is the idea according to which “just as pure narrative would be unconscious act, so pure significance would be an incommunicable state of consciousness, for communication begins by constructing narrative” (15, my italics). The epiphanic and pragmatic planes are hence reciprocally dependent.

22. Cf. Foster, Fictions of the Irish Literary Revival, 236–40, in particular 239: “Yeats hoped that Hanrahan might be accepted as a once-historical figure and then, by way of Yeats’s stories, pass into Irish legend and thence into folklore.” In creating a character who follows the opposite path to many characters drawn from the tradition, it is correct to recognize Yeats’ desire not only to emulate the tradition, but also to repay in person its great generosity in terms of material offered to his poetry.

23. Cf. ibid., 243: “Stephens was in fact happiest when observing unconsciously the laws of folk narrative” (my italics).

24. Yeats, Irish Fairy Tales, 47.

25. Ibid., 67.

26. See ibid., 227.

27. Ibid., 54.

28. See James Stephens, Irish Fairy Tales (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1979), 3–31.

29. The first story in Irish Fairy Tales is not only a refined example of the tale within the tale, but its function extends to the very value that Stephens asks his reader to understand. Cf. Martin, James Stephens, 133: “It is not only an infinitely reflexive narrational method, it is also a method by which the reader is never permitted for long to suspend his disbelief that what he is reading is fiction: continually he is startled by a casual shift from one world to the next, from one narrator to the next, one story to the next.”

30. A necessity felt all the more in a context in which “Fairyland actually exists as an invisible world within which the visible world is immersed like an island in an unexplored ocean, and it is peopled by more species of living beings than this world, because incomparably more vast and varied in its possibilities” (Walter Y. Evans-Wentz quoted in the “Introduction” to Yeats, Fairy and Folk Tales of Ireland, XI).