8

Between the Fairy Tale and the Tale

The Five Phases of the Fairy Tale

To return to an issue only touched on at the end of the Introduction, I think the moment has come to examine a question that is central to our research. We must identify the fundamental levels through which to observe the birth and development of a traditional story. The objective is now focused specifically on the forms assumed by the fairy tale on the basis of the various levels of elaboration that, in the course of time, mold it and guarantee it a certain configuration. We are entering an area very different from that put forward by Foster.1 As the classical conception of the genre imposes, he adopts the notion of the fairy tale (or the folktale) exclusively in terms of the extreme outcome of the narrative itinerary set off by an event or an experience, the final stage in a precise evolutionary process. Now, instead, the opportunity is offered to our analysis to recognize and study the principal phases on which the evolution of the fairy tale is modeled, which from a partial level of the narrative progression extends to take in all these levels. It will no longer represent a point of arrival but a structural constant. In view of this constant, a rigid codification of the narrative material into genres and subgenres will demonstrate all its relativity, since each of the phases identified will not only outline a partial aspect of the elaboration of the fairy tale, but also a form subject to transitoriness. Hence, a purely dynamic scenario emerges, in which each step should indeed be analyzed and appreciated in its particular nature, but always relocated in the wider context of the general principles on which the transversal validity intrinsic to the fairy tale rests. Whereas Foster limited his range of action exclusively to the context of folklore, in our case, the horizon must be widened to embrace the literariness true and proper of the story. In the phases that distinguish the evolution of the forms, contents, and functions of the narrator in the fairy tale, it is correct to perceive an exemplary itinerary that leads progressively from orality to writing, from folklore to literature, from the unknowing character to the skillful author. Moreover—and this aspect deserves all our attention—in the course of its trajectory, the fairy tale is able to lead us back to the original phase, in which it is possible to hypothesize the congruency of the conflictual visions of fabula and historia. This congruency declines precisely at the moment that the fairy tale begins its voyage, accentuating constantly its fabulousness at the expense of historicity, which is obliged to follow an independent path.

From my point of view, we can divide the parabola of the fairy tale into five fundamental phases, according to a scheme that tends to claim wider validity, to the point of including the entire sphere of narrative expression. The scheme is a general one, within which it is possible to observe the specific path taken by each fairy tale. Thus, as it is possible to individuate what develops along the entire spectrum of the five phases, it is also possible to verify what restricts it to a more limited arc, arresting its course in an intermediate phase or skipping one or more phases and moving directly from the first to the last. This variety of outcomes is explained by the fact that each of the phases following the first always represents a narrative form that, although susceptible to transformation (with the passing of time, the spreading into space, and the change of the narrating subjects), also possesses the capacity/opportunity to arrest the chain of mutation and to crystallize it.

At the basis of any disquisition concerning narrativity, and all the more so regarding the fairy tale, it is necessary to theorize the existence of a preliminary phase, corresponding to the moment at which what will later be absorbed and expressed by the narrative act itself is enacted or only imagined. In substance, this is the phase, constantly evoked in the preceding pages, which up to now has been indicated by the neutral and all-inclusive term event, which is moreover the term adopted by Foster. Foster also speaks about experience, a notion that better reflects the lived nature of so much of the material connected to the folk narrative. But neither term weds itself now to the needs of a discourse that is becoming deeper and more specific.

It seems to me indispensable, therefore, to adopt a less neutral term, more suited to reflect the characters and values intrinsic as much to the fairy tale as to the narrative tradition as a whole. Both ambits cannot, in fact, be restricted or extended, according to point of view, within a perspective in which any event has the faculty to propose itself as a source of inspiration. Potentially, nothing is irreducible to a narrative rendering. But this capacity must measure itself with a set of parameters that regulate its approach to the context, whether real or imaginary. I refer back to what was said in the previous chapter about the fairy tale as a vehicle of meaning. An effective meaningfulness can only be obtained if the discourse starts from a background that forms a repository of what is recognized as really meaningful. One presumes, therefore, that all that passes from pure eventuality to the narrative act is held to pertain to this exemplary background, a background in which lie the indispensable foundations for a discourse that aspires to acquiring universal validity. Here, inevitably, the term myth returns to our attention, to the extent that it seems to me the best adapted to expressing the sense of the concepts to be included in the first phase of the fairy tale. The word myth, in the lowercase, having been already adopted in a somewhat different perspective, is now taken up again.

We have already seen the significance which Myth (with a capital letter) had for the narrative tradition. In the wake of this, one now comes to deal with myth. It returns to the idea of the primordial, from which every story flows and gains substance. In this term, it is possible both to distinguish a system of data, parameters, and factors of archetypal scope2 and to recognize the presence of figures and events in a context in which the common notions of reality and fiction3 intersect so closely as to render a repertory of themes and motifs that give origin to the most varied of narrative modalities. Interpreting as myth every event, or part of it, that lies at the origin of a narrative tradition implies recognizing its independence from questions linked, for example, to the common notions of veracity or credibility. Any event able to distinguish itself from limited context of time and space and to be absorbed even within the simplest narrative elaboration ceases to be an event and becomes myth. Beginning as the patrimony of a single individual, this situation extends to take in an ever wider community, given that the circumstances favor its diffusion. In any case, that particular myth will enrich a patrimony in which all the exigencies of narrative will be satisfied. Myth is to be considered as the first indispensable phase with which the evolutionary parabola of the fairy tale must measure itself. Myth can be considered as such insofar as it provides the evolutionary parabola that the fairy tale must embrace. It can be conceived as the ground zero of narration, in that it furnishes the material that can potentially be narrated. At least one successive phase is required, however, that is capable of fashioning, according to the given narrative canon, this material itself, so that it is effectively available to an audience that can enter into the virtuous circle of narrativity.

Myth is followed by the phase of the anecdote, which should be interpreted as the simplest phase of narration since it refers to the first testimony available for a particular event. Anecdote is the passage leading to a personal experience, undergone in the first person, indirectly or in pure imagination. It opens itself to an initial relationship with the exterior. It is fair to say that this second phase functions as a channel through which the myth in question embeds itself in a narrative context. And it is in this eminently pragmatic context that resides its main function and its extreme instability on the temporal plane, in the sense that it maintains its validity only insofar as the account of its narrator lasts. Nor is it without significance that one speaks here of an account and not of a story, to the extent that there is still no authentic narrative project. This is true in the sense that the properly narrative function is superimposed by the informative function, which renders the anecdotalist no more than a source—the only one—that can furnish visibility to an event perhaps far distant from the listening community.

One may speak of a project only when the anecdote is taken up by a member of the audience, one who is capable of grasping a narrative quality in what he has heard from the source and of exerting himself, so that the anecdote may take the next step and become legend (note the use of the lowercase to avoid confusion with the use made previously of the same word). This marks the third phase of the narrative elaboration of the fairy tale. At this level, myth depends above all on the logic of the community, in the sense that, spreading within a given community, it undergoes a process of appropriation on the basis of which its meaning depends strictly on the conditions and the needs of those who are at the same time beneficiary and recreator of the narration. Legend involves participation in what is narrated, since it remains thus only as far as the link is preserved between the event and the context in which it was received for the first time (which, moreover, is presumably where it was set). Hence, preserving this link implies preserving, in theory at least, the truth of what is narrated because in this way one preserves a founding tradition for the community.

The fairy tale can arrest its development in the legendary phase, and there are outstanding examples of this in Yeats’ collection. This is all the more plausible when narrative tradition remains confined within the limits of a small community in which oral transmission, albeit altering in form and content, maintains its original value as a legend connected to local myth. It is also the case that legend can be acquired as such thanks to the advent of writing, which imposes an artificial limit on the evolution of the fairy tale. But writing can also move in the opposite direction, permitting a legendary plot to pass into the fourth phase, perhaps by intervening directly on the anecdote or even on myth itself and immediately giving it a folktale rendering. The folktale (fiaba in the original Italian of this text) is in fact the fourth phase of the evolution of the fairy tale, a phase, that can be reached also on the basis of the natural oral progression of the legend. It is certain that, with the process being illustrated here, folklore allows always more space to literature, orality to writing. The phase of the folktale comes into play when community logic is replaced by a wider one in which narration, rather than limiting myth to a more or less particular context, displays its general value, so that more than one community is capable of recognizing itself. This explains how, in this phase, the concept of a more or less historical truth is replaced by a wider human truth,4 without taking into account that the purely aesthetic value of the story gains greater relevance. These changes of perspective are reflected in the form and content of the folktale, which tends to obliterate any precise reference to time and place and to stylize its characters, thus giving an increasingly accentuated impression of artificialness,5 or at least of an elaboration on the part of a narrator for whom the consistency of the myth narrated has decidedly passed into the background. Moreover, it is the inexorable passing of time itself that tends to distance to an ever greater degree the traditional memory of the original source6 and subject it to the “jurisdiction of narrative laws of type and genre.”7

In any case, the fairy tale, even in the phase of the folktale, continues to be the product of an oral tradition, regardless of the extent to which the latter has widened its perspective with respect to the restricted original context. The phase of the legend and of the folktale are the two fundamental levels, coexisting and evolving into each other,8 through which the patrimony of myths pertaining to a particular tradition gains narrative expression. The fairy tales in Yeats’ collection conform to this. Despite how they have been modified more or less in the transition from orality to writing, they are the popular elaboration, in the broadest sense of the term, of all that enters into the category, adopted in the last chapter, of the imaginative store. This store is made up of myths that are identifiable as such, in that they have been elaborated through the process, complete or partial, of anecdote–legend–folktale. Without this store, Yeats’ and Stephens’ collections would have been inconceivable, as would scientific works, such as the Handbook of Irish Folklore by Ó Suillebhain, which attempts to gather the entire corpus of themes and motifs in the Irish tradition. If we isolate, within this repertory, the chapter entitled Mythological Tradition, we find ourselves in practice dealing with all the myths from which the greater part of our fairy tales originate and gain substance, since this section contains the most relevant number of figures and events connected to the category of the indefinite.9 This repertory can never be considered definitive, both because it is always possible that a new myth will emerge on which to build a tradition and because it is fair to think that others have been canceled out by an insufficient narrative tradition, either through conscious choice or unfavorable conditions.

The evolutionary parabola of the fairy tale does not exhaust its potential here, however. There is in fact a fifth phase, which leads to a definitive detachment, on the one hand, from the oral context and, on the other, from the folkloric. This narrative form that, in the absence of a valid alternative, I shall call the novella, avoiding thus both the insufficiently precise term tale and the adoption of the word fiction, which would probably provide the most exact sense of what one is attempting to theorize.10 (The original value of the “novella” will be set aside, despite the fact that no great difference exists between it and the topic under consideration here.) By novella is intended the literary story, hence it refers to the phase in which the fairy tale has been completely absorbed into a literary logic, in which the original myth has been completely uprooted from its live context and is transferred to an absolutely aesthetic context, subject to the poetic of a single author, who is always a writer. In this way, the fairy tale ceases to be common property and ceases to undergo the continual alteration of oral reworking. In this phase, an artistic object is produced and deposited once and for all in the literary tradition. Whereas in the preceding phase writing was an external factor that arrested an evolution in action, the novella is immediately identified with the form that written elaboration imposes at the origin. Thus, if a writer is the first to approach a myth handed down in no other form, an immediately definitive version of this myth will be transmitted. In the case in which this writer is a historian, the myth will be subjected to the more rigid laws of historiography and transmitted as a historically real event, attested to by a written document. The consequence is, if testimony such as that, for example, cited in the last chapter of Giraldus Cambrensis regarding the ghostly island is considered reliable, then it will take on the value of historia and can aspire to being studied from a scientific viewpoint; if, on the other hand, it is not considered reliable and is the pure fruit of invention, then we are dealing with an approach of fabula within the creative logic of the author in question. Writing, therefore, in parting from the one source, can impose both a historical and a literary tradition.

The texts collected by Stephens are certainly fairy tales and derive certainly from elaboration in legend or folktale of a tradition with its roots in mythical patrimony. However, these texts have been absorbed into a fully formed poetic, for which the figures and events inherited from tradition assume an entirely innovative value, comprehensible exclusively for their author, who is the most advanced exponent of a formal and thematic evolution which, as has been seen, is divided into five phases. While the logic of Yeats’ collection is that of faithful conservation—beyond the more or less wide margins of literary elaboration introduced by the collectors—of a narrative patrimony that maintains, even in a written context, its relationship with the oral and popular background, in Stephens we observe a decisive leap toward the independence of the text, in which the fairy tale becomes to all effects a literary genre, that we have defined as the novella.

What has been preserved, from the first to the fifth phase, is the dialectic definite–indefinite, without which one could not speak of the fairy tale. The Twelve Wild Geese11 is one of the purest examples of the folktale, but no one can prevent us from thinking that if Yeats had been capable of approaching the same fairy tale one or two centuries previously, he would have found it in the legendary phase, with whole series of precise references to the original context. Likewise, what seems actually to be a fairy tale still in the anecdotal phase—How Thomas Connolly Met the Banshee12—if it had been collected a few years later, could already have been a folktale, with Thomas Connolly transformed into an anonymous hero in search of adventure. In each case, one is dealing with forms that can decline from one moment to the next, in which the movement manifests itself and, albeit in an altering context, breaks down each time the barriers separating one or two dimensions of the real. This movement should be read as the unchanging peculiarity of the fairy tale, and it is only on the basis of it that one can set up a profound comparison with other narrative ambits. The five-phased model of evolution just outlined is only the exterior manifestation that can plausibly be discovered in contexts that lie outside the fairy tale, since the model not only traces back narrative processes, but also traces more widely historical and cultural ones.

The Fairy Tale and the Pseudo-Fairy Tale

It has already been said that Stephens’ collection should justly be considered a collection of fairy tales, at least according to the canons developed in the course of this research. Each of the ten tales is effectively founded on the dialectic of definite–indefinite, two notions that gain specific meaning on the basis of a precise theoretical framework. However, one should note that when reading the text of The Little Brawl at Allen13 not even the shadow of this dialectic appears almost until the end. It is, in fact, the narration of a contest, as cruel as it is comic, between the ranks of two Fenian heroes, Fionn and Goll mac Morna, characters belonging to the same dimension, and the tale lacks even minimum intervention from indefinite figures. The events take place on the plane of Legend (note the capital letter), until in the last paragraph it is narrated how Goll mac Morna liberates Fionn and his knights from the Christian hell: there is, therefore, an opening toward the transcendent indefinite, the Otherworld imported by St. Patrick’s preaching.14 Without this, it would have been impossible, strictly speaking, to rank it as a fairy tale.

On the other hand, the following story, The Carl of the Drab Coat,15 is based on events set almost entirely in the indefinite dimension, in which Fionn again interacts with his army: here, one is dealing with a fairy tale in the fullest sense of the term.16 What distinguishes one from the other, given that both belong to the same category, is the fairy density, if one can use such an expression, in the sense that one tale allows much more space than the other to interaction with the indefinite. The second story furnishes a much more detailed image of an otherworldly dimension, whereas in the first, this seems to be a simple corollary to a story focused on a far different theme. Thus, one is faced with quantitative differences, just as in both cases the context remains, so to speak, that of the pure fairy tale.

The issue becomes more delicate when one comes to examine the stories in Yeats’ collection. Can one consider as a fairy tale a story that narrates the conflict (or better, the lack of conflict) between Finn and Cú Chulainn, or between two heroes both belonging to the plane of Legend?17 And how is one supposed to assess the events narrated in The Haughty Princess,18 in which a prince and princess pertaining absolutely to the same dimension first confront each other and then get married? Finally, what should one say about the tricks with which Donald O’Nery repays the misdeeds of his two jealous neighbors?19 From a theoretical point of view, all three stories are absolutely extraneous to the logic recognized up to now in the fairy tale. In none of them does a dialectic occur between totally different dimensions—everything takes place on a one-dimensional plane. In these stories, one is dealing with three exceptions from a whole made up of pure fairy tales. Into what category should these three exceptions be placed? There seem to be two possible paths to a solution. On the one hand, one could eliminate the adjective “fairy” and define the three stories in question as simply unspecified “tales.” In this case, the fairy tale would become a more complex expression of a zero degree represented by the one-dimensional tale. On the other, one could examine the texts more deeply, to discover whether sufficient elements exist to make them candidates, albeit by a shortcut, for the class of fairy tale. This second path would profile instead the existence (or at least the identification) of spurious forms gravitating around the fundamental category of the fairy tale, a sort of constellation of pseudo-fairy tales.

Adopting the first strategy would mean recognizing the importance of the theoretical framework through which the notions of the definite and the indefinite were individuated, notions based on a conceptually complex systematization of the world, so that a story becomes a fairy tale only if it can make this complexity perceptible. From this point of view, it is permissible to infer that the simple tale, whatever its exterior characteristics might be, represents a limitation to the more authentic potential of narration. What may be simply evoked or imagined by a tale becomes real in the fairy tale. Confrontations that remain imaginary in the tale, in the fairy tale gain pragmatic consistency. The three stories in question, therefore, are located beyond the threshold discussed in a previous chapter and develop a dialectic between characters in a system that remains closed to the exterior. Hence, their epiphanic value is limited to a context that is presumably known from the beginning.

If, instead, one examines the texts under discussion according to a less rigid conception of the dialectic of definite–indefinite (and is thus less obsequious to the multidimensional conception proper to the Irish fairy tale), it is possible to recognize elements that, organized from the correct point of view, can identify alternative or weak variants of the fundamental, strong model of the fairy tale—almost as if the latter were the first source of storytelling, from which forms gradually less marked by the original dialectic descend. Hence, the contest between Finn and Cú Chulainn would be confrontation between a more definite character (Finn) and a less definite one (Cúu Chulainn), according to a model that has been reorganized with respect to one of real opposition between the pure definite and the pure indefinite.20 Nor should one undervalue the fact that two concepts, such as those just evoked, can be interpreted in a different manner depending on the space–time context in which they are elaborated. Thus, one may also hypothesize a context, human or purely narrative, in which Finn and Cú Chulainn represent the maximum tension between definite and indefinite. Just as, vice versa, a context can be hypothesized in which such a tension cannot be established insofar as everything is perceived in a definite key and no element is able to institute an indefinite dimension: this holds true when considering the situation presented in the age of Myth. In practice, the value assigned to the notions of the definite and the indefinite is connected to a sort of preestablished pact between the storyteller and his audience, between the text and its context, which, in its totality, accounts for the plausibility of the fairy tale. From this point of view, it is with some surprise that one notes the presence of the three pseudo-fairy tales found between the pages of a collection oriented programmatically toward demonstrating the dialectic between parallel planes of reality. However, one would be no less surprised to come across a drift into the fairy tale within a collection of realistic tales. In both cases, an ineluctable fact remains: narrative—and above all apparently irreconcilable cultural typologies—can, according to the context in which they operate or on the basis of specific choices of the storyteller, cross paths and give birth to narrative products that cannot be better specified, or that can be most correctly characterized precisely by virtue of their mixed nature.

The fact remains, however, that one may conceive of a sort of antithesis between the neutral notion of the tale and the qualitatively determined notion of the fairy tale through a confrontation in terms of the approach to the reality narrated. If one is justified in maintaining that every story requires a dialectic to be set up between one’s own and the others’—hence to a relationship between at least two poles at a more or less greater distance from each other—it is equally correct to recognize the substantial nature of this relationship. When literature sends its characters off on otherworldly journeys or faces them with supernatural apparitions, events that, in general, overflow any threshold of verisimilitude more or less imposed or more or less accepted, it constructs an effective relationship between one’s own and the others’. It operates analogously to the situation of the storyteller, who acts in such a way as to lift the veil that normally hinders human perception. It is as if, in syntony with what happens in the field of the oral tradition, an open system existed, in which the story unveils a universe whose confines separating space–time dimensions reveal themselves to be porous and open to an exchange between planes of reality that otherwise would be hidden from each other. When at least one character is allowed not only to depart and move in a horizontal direction, but also to escape (moving, therefore, in a vertical direction), it seems fair to me to recognize in the story a fairy tale. The latter denomination models itself clearly on an Irish context, influenced decisively by the interaction between folklore and literature, and hence set against a determinate background of myths (in the sense given in this chapter) in which fabula and historia interpenetrate, but which could equally permit the identification of a given whole transcending the narrow limits of a single narrative tradition.

However, just as limiting ourselves to the Irish context has made it possible to elaborate a certain idea of the fairy tale, in the same way one must limit the field of research when one moves to examining that area pertaining to the closed system. This area is delineated by an unspecified conception of the tale, in which there exists the expression of a universe containing an impermeable barrier between a preexisting reality and another potentially extending above or below it. The character of this sort of tale is able to depart, to make a movement, but, in effect, he remains anchored to his plane of origin—that of History—even when he simulates, perhaps through an act of imagination connected to the fairy tale itself, an escape to a territory lying beyond an insurmountable border. It is necessary, then, to recognize James Joyce as an author who best presents, in a work that re-evokes the narrative collections examined up to now, a tale built in this way. This author is as close as possible, in time and space, to those who have been chosen as representatives of the fairy tale, one who has perhaps taken a critical stance with respect to the literary renewal of the traditional patrimony adopted as a source for the specific definition of the fairy tale.

The Joycian Tale in the Light of the Fairy Tale

Joyce was a writer who, from the outset, maintained an openly dissonant attitude to the Irish Revival and substantially rejected a certain “imaginative incompleteness and senility of mind,”21 expressed by the folk narratives that so many of his colleagues strove to recover from the living voice of the peasants. Joyce chose voluntary exile to limit the influence, which he maintained detrimental, of his homeland on his creativity. He could express, therefore, in the most effective manner, the capacity of literature to free itself of the conditioning of the oral and popular tradition. To test the solidness of this hypothesis, it would be opportune to examine Joyce’s short story collection, Dubliners, as a text that can most easily be compared to the collections of Yeats and Stephens. Examining this on the basis of the criteria established in the analysis of the fairy tale, we seek to locate a less neutral and more specific sense and link it to the notion of the tale and everything connected with it. The objective I have set myself, conscious of the limits of such partial research, is that of discovering what type of relationship exists between two ambits that could create a fundamental bipartition in the field of narrative, just as they could institute a sort of convergence on shared ground, where eventual relationships of dependency between one and the other might perhaps be perceived.

It seems to me that Dubliners can be considered the ideal and most coherent conclusion of the process that began with the works of Yeats and Stephens. Whereas Yeats’ text represents the complete acquisition of a national tradition in which folklore makes its entrance into a renewed literary context, and whereas in Stephens there is a partial readoption of this, in keeping with a more autonomous literary poetics, Joyce’s text displays instead a definitive detachment of literature from tradition, or rather—in keeping with our aim—of the tale from the fairy tale. Through Dubliners, it is in fact possible to take a step backward and reconnect to the ambit from which Yeats made his start. The stories set in Joyce’s Dublin seem to provide the most representative image of the antithesis between closed and open systems, but in this same context, the idea of a synthesis between the two forms of the same universe seems perceptible or conceivable.

Although admitting that this is not the most suitable context in which to attempt an intensive analysis of a work as complex as Dubliners, which would also require a parallel treatment of the rest of Joyce’s work, I shall approach a reading of the text in question by isolating a few significant passages, best adapted to the scope in hand and examined naturally through the more or less deforming interpretative lens consolidated in the preceding pages. These brief passages are nonetheless capable, in my opinion, of revealing a deep structure that sustains the work as a whole. This structure manifests itself with certain immediacy in An Encounter, which, as Harry Levin correctly deduces, is a crucial crossroads, with its emblematic title, for a large part of the other stories in the collection.22 This observation evinces a theme (which is also a narrative instrument) central to Dubliners—that of the encounter, in which two or more characters, antithetical in some way and repositories of more or less divergent worldviews, cross paths on their journey through Dublin and set up a more or less close confrontation.

The main character of An Encounter is a boy who, like his playmates, is enthralled by the marvels evoked “in the literature of the Wild West,”23 hence by a reality that is entirely another with regard to the limited space of the city. An authentic attraction leads the narrating voice toward the limitless horizons of the American plains. His desire for adventure is expressed eloquently: “I wanted real adventures to happen to myself. But real adventures, I reflected, do not happen to people who remain at home: they must be sought abroad.”24

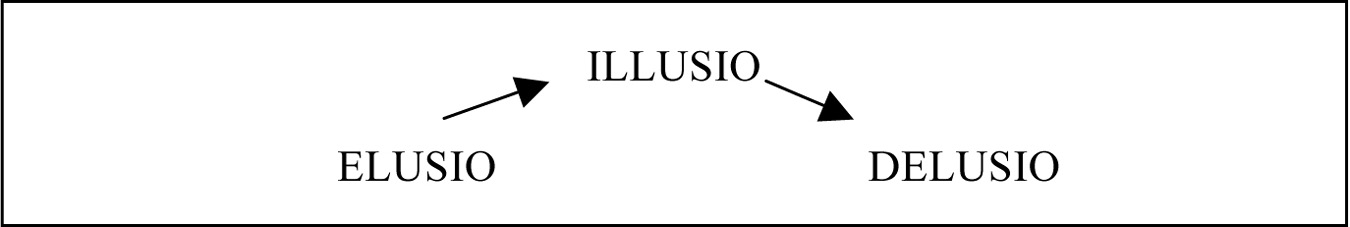

On the one hand, there is the need to escape, and on the other, the awareness that a movement is required to reach the desired dimension. For as long as the boy continues to simulate the adventure while staying at home with his friends—and thus on the definite plane—the situation is still that of initial stasis. More particularly, it seems to me that one can introduce a specific concept, that of ELUSIO, in the Latin etymological sense of being ex- (out of) lusio (play, entertainment), intending the second term as much in an immediate meaning of hedonistic pleasure as in a profounder sense of spiritual wholeness.

Just as the hero of a fairy tale, the character in Joyce’s story decides to escape from his context, to enter into material contact with a superior dimension known only through stories told by others. His journey to the Pigeon House—in reality simply a power-station—is to be understood as if it were a movens, a long voyage toward something never seen before from close quarters. However, the journey is too long and costly to be brought to an end and must finish in a field that is simply far from home. In this field, the interaction of the main character and his companion with the indefinite takes place. The indefinite takes on the appearance of an old man, the encounter with whom provides the title of the story and is therefore the most important section. This phase of interaction can be read, in this context, as a sort of ILLUSIO, also here adopting the etymological sense of in-lusio, hence of being within the game that previously was only imagined.

It is nonetheless clear that this equivocal character, albeit other than the main character, is far distant from the mysterious and coveted Pigeon House. From this viewpoint, therefore, the term illusion should also be read in the immediate sense of a deception undergone by the hero who has searched for the indefinite in the wrong place—rather, a real escape has been denied him.

Faced by this discovery, there is no alternative but for the hero to retrace his steps (rediens), with the added fear of having met a character who is perceived as being dangerous. The boy returns to the everyday reality from which he had attempted to escape for a day, but which in the end imposed itself to reestablish the situation of initial immobility without anything new having been brought into play by the movement. This is the final stasis, which should be interpreted in the canons of a DELUSIO, in which to the etymological sense of provenance and exit from (de) the game (lusio) should be added the specific sense of the Italian term delusione (disappointment), or rather that of an experience that has betrayed one’s expectations.

Proceeding in such a way as to re-evoke the form of the fairy tale, Joyce’s story has demonstrated the previously mentioned impermeability that encloses the definite plane identified by the tale. Whereas in the fairy tale, the hero witnessed an epiphany of another world, the hero of this tale observes an auto-epiphany of his own world which, deceptively, does nothing else than continually reassert itself. It is not by chance that Joyce himself spoke of Dubliners as the expression of paralysis, on both the dynamic and the mental levels. The same can be said regarding the use of the term epiphany, from which transpires as much the meaningfulness of the story as the degraded revisitation of a concept originally of far deeper significance.25

In the attempt to clarify further the structure of An Encounter—in which it is possible to recognize a form that practically distinguishes almost all other texts in the collection—it would be opportune to provide an illustration (see figure 8.1):

Figure 8.1.

Here, the arrows represent, respectively, movens and rediens, and one can see how the movement of the tale is enclosed within a polygon. Thus, the duration of the movement is limited by the restricting net of a context from which it is impossible to escape, one that allows only the appearance of motion.

But if the hero had succeeded in reaching the Pigeon House, could one have spoken then of a real escape, and hence of a fairy tale? This same question was posed regarding those three stories of Yeats that deviate from the norm, where we posited that it might be better to introduce the category of the pseudo-fairy tale. Also in An Encounter, it is correct to recognize that the Dublin power-station (The Pigeon House) cannot, strictly speaking, incarnate the category of the indefinite, but it is equally permissible to perceive in the main character’s sublimated vision of this place the visible materialization of his dreams of escape, the only concrete possibility of reaching a reality that is other than everyday monotony. Under this light, the Pigeon House could be interpreted as a pseudo-indefinite and the tale would enter into the category of the pseudo-fairy tale.

We know, however, that the destination is not reached and that An Encounter therefore moves in an absolutely horizontal space. This space is also totally closed in on itself, as exemplified in the graphic illustrating the dynamic and conceptual progression underlying the story. This is demonstrated by the rest of Joyce’s collection, in which one discovers an irreconcilable opposition between a vague desire to escape and the constant frustration of this posed by a static and hermetically sealed environment. No less significant in this regard are other passages from the text, in which one can see with further clarity this approach to Joyce’s narration.

In The Boarding House, regarding the male character who has been trapped in a net laid by a mother in search of a husband for her daughter, one reads: “He longed to ascend through the roof and fly away to another country where he would never hear again of his trouble, and yet a force pushed him downstairs step by step.”26

The man, finding himself with no way out, desires to fly from the roof and to land in another country, serving himself therefore of an authentic fairy tale image. His flight is purely imaginary, however, since he remains confined to the ground by an unknown force. He would like to move skyward, symbol at once of salvation and liberty, but the context obliges him to go downstairs, to remain at a lower level and to accept the consequences of the trap laid for him by the mistress of the boarding house and her daughter. If any character manages to escape from the initial stasis, it is the daughter who, with her mother’s help, succeeds in making the man marry her. She abandons the family boarding house and moves to a less definite context.

In A Little Cloud, Little Chandler, enchanted by the exotic fascination emanating from an old friend from his student days coming to visit from London, reaches out toward a new life in an elsewhere that is even specified: “Every step brought nearer to London, further from his own sober inartistic life.”27 A few pages further on, the main character finds himself again faced by the opening dilemma: “Could he go to London? There was the furniture still to be paid for.”28 Following a revelatory encounter, the hero becomes aware of the prosaicness of his life, compared to the poetic life that his friend leads in faraway London. Hence, the desire matures to reach that indefinite place in which he hopes to make a decisive change in his life. However, returning home, the prosaic consideration that there is furniture to pay off is enough to dissuade him from any real movement and to fix him once and for all in the definitive stasis of Dublin.

In Counterparts, the main character, Farrington, lives a gray existence confined to an anonymous office. This is the ideal situation in which to instill a strong desire to escape to an elsewhere that would give sense to an absolutely static life: “His imagination had so abstracted him that his name was called twice before he answered.”29 Once again, it is the imagination that leads the hero far away from reality, if only for an instant, to a much more satisfying dimension than that in which he really lives. However, at the second call, he is obliged to return, also in the mind, to the close confines of his workplace. Farrington’s frustrating condition becomes even clearer in the compensation he seeks by getting drunk in the pub, then returning home and mistreating his son, on whom the rage of a man continually constrained to coexist with an unsatisfying definite vents itself.

We have seen three examples demonstrating unequivocally the closure imposed by the city, but also the inability of the characters of the tales to pass the threshold of the imagination, to acknowledge and give substance to their desires. A claustrophobic environment has unfolded before our eyes, closed in on itself. Here, too, are an array of authentic antiheroes, who never manage to undertake the journey leading finally to the discovery of the indefinite lying beyond the limited, but comforting, reality of Dublin. The escape takes place on an exclusively mental level, where there is no risk of being overcome by the unpredictable experience of the other, or rather of what escapes consciousness, because no one has taken the responsibility of leaving and returning with testimony of the epiphany of another world to share with their community.

However, an examination of Dubliners cannot exhaust itself with the awareness of the stories being incapable of transforming themselves into fairy tales or even pseudo-fairy tales. To glimpse more enticing horizons, it is necessary to approach the most complex story, which significantly closes the collection. I refer to The Dead, a text in which the dialectic of the tale–fairy tale opens on a far wider perspective and permits therefore a far deeper understanding of the phenomenon under examination. In effect, for almost all the long story, we seem to find ourselves immobilized in the classical Dublin situation, between the four walls of a house in which is celebrated the traditional rite of Christmas dinner, during which range of definite humanity does no more than reflect itself. Only the last pages open up an unexpected horizon, when the young couple Gabriel and Gretta Conroy, return to their hotel. There, the woman is surprised by the memory of a youth, Michael Furey, so in love with her as to have unhesitatingly put his delicate health at risk, up to the point of encountering an early death. This traumatic event emerging from the past disturbs not only Gretta but also Gabriel. Two passages are particularly significant regarding what happens to the main character:

A vague terror seized Gabriel at his answer [“I think he died for me,” as Gretta says regarding the death of Michael Furey], as if, at that hour when he had hoped to triumph, some impalpable and vindictive being was coming against him, gathering forces against him in its vague world.30

His soul had approached that region where dwell the vast hosts of the dead. He was conscious of, but could not apprehend, their wayward and flickering existence. His own identity was fading out into a grey impalpable world: the solid world itself, which these dead had one time reared and lived in, was dissolving and dwindling.31

The first quotation reports Gabriel’s reaction to a critical moment of his wife’s story, when she reveals that a boy died out of love for her. He becomes aware of the presence of an impalpable being, coming from an indefinite (vague) world, which seems ready to revenge itself, at his cost, for its bad luck. The main character, although remaining in a hotel room, perceives the presence of a figure pertaining to the indefinite true and proper; he becomes the witness of an invasion by a figure pertaining to the transcendent. His experience is a purely interior one, to the extent that Gretta is not even slightly aware of it (at least as far as the narrator lets us know), but it is nonetheless indicative to note that, after so many vague attempts at escape, in the last tale Joyce, putting a close to the context of Dublin, should include mention of an interaction with an indefinite dimension.

The second paragraph portrays Gabriel’s situation after his wife has finished her story and fallen asleep. He is alone now and is aware of an episode from Gretta’s past of which he had been completely ignorant. This awareness is an epiphany in the fullest sense of the term, because through it the main character enters into contact with a dimension to which he had paid no attention until now. His wife’s story leads his soul almost to detach itself from his body and escape into a region inhabited by the “vast hosts of the dead,” no longer just Michael but all those who pertain to the otherworldly dimension that now presents itself to Gabriel’s perception. He is not simply imagining an escape into another world, but is conscious of the existence of a world parallel to that in which he is living, of its different nature and of the elusiveness of a world that removes itself from the definite laws of the solid world. Through the altered consciousness of the hero (no longer an antihero), two dimensions coincide in the same space; it does not seem that one is dealing with a purely interior interaction, since Gabriel feels his identity disappear and sees his definite reality dissolve, both absorbed into a “grey world” that seems to want to envelope the entire universe. It is as if a primigenial unity of being were being reestablished, as if one were returning, albeit in a decidedly faded light, to the one-dimensionality of Myth. In the last tale, one observes therefore a sort of drift into the fairy tale, or that the narration, which until this moment had remained within an absolutely definite context, has now found the way to break down the barriers of an exceedingly oppressive realism. If we consider Dubliners as one long story, we can note how, after numerous failed attempts to reach an epiphany from a world that is other than the static point of departure, one arrives in the finale itself at reestablishing the link with a dimension that was believed buried for good. Hence, Dubliners is a fairy tale, although of extremely low fairy density. In any case, The Dead seems to demonstrate that the conceivableness of the fairy tale has not entirely disappeared. It remains a narrative potentiality that simply needs the correct conditions in which to manifest itself. And the correct conditions are provided not by any real movements of the characters, but by the narrativity of the text itself, as demonstrated by Gretta’s tale within the tale, through which the gates of the fairy tale open for Gabriel.

More generally, in Yeats’ work as in Stephens’ and Joyce’s, one observes the efforts made by the story and its narrator to upset the stasis of the real through more or less extraordinary encounters. Nothing of any importance would happen if it were not for the epiphany provided by the narrative movement. The profoundest potentiality of this movement expresses itself in the fairy tale, but this requires the active participation of its characters and for the suitable conditions to manifest itself. Hence, when this cannot occur, the tale, despite availing itself of a more limited and limiting point of view, operates in such a way as to invest reality with the magic of the other, an operation that acquires all the more value in a context—such as Joyce’s Dublin—that would seem to offer only the barest resources for the development of a narrative discourse. The analysis of Dubliners demonstrates how, between the realist tale, in the broad sense of the term, and the fairy tale no effective antithesis exists, but rather a convergence in the common intention to displace the “nightmare of history,” to quote Joyce. On the one hand, the realist tale depends on the fairy tale as far as the means—structural and conceptual—adopted to appropriate the tellable material are concerned. On the other hand, the fairy tale depends on the realist tale for the formation of a static context in which to begin the exploration of the (probably boundless) universe that is intrinsic to the idea of the fairy tale.

Notes

1. See supra, “Introduction,” 22.

2. Cf. Frye, The Archetypes of Literature, 16: “The myth is the central informing power that gives archetypal significance to the ritual and archetypal narrative to the oracle” (my italics).

3. There can be no distinction in a field in which there tends to prevail a substantial unity of concepts which only later, in parallel to a certain evolution of humanity, could be theorized separately. This discourse is very close to that concerning Myth as the first stage of the Irish narrative tradition. One can say that myth, in its independence from a precise space–time context, renders something feasible each time that, in the Myth in question, was confined to a rationally inaccessible past. Cf. David Bidney, Myth, Symbolism, and Truth, in Myth: A Symposium, ed. Thomas A. Sebeok (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1965), 8: “According to Cassirer’s Neo-Kantian approach, we must understand the mythical symbol, not as a representation concealing some mystery or hidden truth, but as a self-contained form of interpretation of reality. In myth there is no distinction between the real and the ideal; the image is the thing and hence mythical thinking lacks the category of the ideal.”

4. Cf. Foster, Fictions of the Irish Literary Revival, 216: “The transformation of personal experience into story does not mean that the original conviction or belief is rendered unfounded, insincere, or duplicitous: but it does mean that validity or sincerity or verifiability becomes irrelevant.”

5. Here, the utility of the previously quoted contribution of Lüthi to the definition of the formal differences between Sage and Märchen becomes clear, once their pertaining to a common platform is recognized.

6. Cf. Zimmermann, The Irish Story Teller, 583: “After a certain time the eyewitness’s account is replaced by a stylized and stereotyped version” (my italics).

7. Foster, Fictions of the Irish Literary Revival, 216.

8. Not only the natural progression anecdote–legend–folktale, since the opposite must be taken into consideration, a sort of devolution. Cf. ibid.: “I suspect, too, there might be some devolution: a Märchen . . . is localized, a local legend is passed off to the outsider as personal experience.”

9. See Seán Ó Suillebhain, A Handbook of Irish Folklore (Dublin: Educational Co. of Ireland for Folklore of Ireland Society, 1942), 440–519.

10. Cf. Frye, The Anatomy of Criticism, 366: “FICTION: Literature in which the radical of presentation is the printed or written word, such as novels and essays.”

11. See Yeats, Irish Fairy Tales, 297–303.

12. See ibid., 118–21.

13. See Stephens, Irish Fairy Tales, 157–72.

14. In Stephens’ text, there is an authentic rebellion on the part of Goll mac Morna, who is not willing to allow his world be eaten up by the infernal perdition imposed by Christian law. His rebellion is successful, as if to confirm the capacity of Legend to survive the advent of a new Otherworld and its coexistence with the plane of History. In the following passage, one can see his attraction and nostalgia for a period more suited to the spirit of the last true exponent of the Irish Revival. See ibid., 172: “And, later on, when time did his worst on them all and the Fianna were sent to hell as unbelievers, it was Goll mac Morna who assaulted hell, with a chain in his great fist and three iron balls swinging from it, and it was he who attacked the hosts of great devils and brought Fionn and the Fianna-Finn out with him.”

15. See ibid., 173–200.

16. Stephens’ first lines, moreover, leave little room for misunderstanding (ibid., 175): “One day something happened to Fionn, the son of Uail; that is, he departed from the world of men, and was set wandering in great distress of mind through Faery. He had days and nights there and adventures there, and was able to bring back the memory of these.”

17. A Legend of Knockmany, in Yeats, Irish Fairy Tales, 283–96.

18. See ibid., 311–13.

19. Donald and His Neighbours, ibid., 317–20.

20. Albeit through the deforming lens of humor, which probably owes much to Carleton’s transcription. In Cú Chulainn’s return to Ireland to establish his superiority over Finn, who is guilty of having obscured his fame (but avoids the meeting in every way possible), one can glimpse a sort of confrontation between the epic idea of heroism, incarnated in the protagonist of the Ulster Cycle, and a more modern conception of it, reflected in the far from heroic behavior of Finn. Where the latter avoids direct conflict with Cú Chulainn, knowing he cannot compete on the level of brute force with an individual closer to Myth than himself and therefore more superhuman, and in the bloodless defeat that Cú Chulainn undergoes due to the tricks hatched by Finn’s wife, one can read the incompatibility of the Celtic Heracles with a time in which Legend had assumed more fictional tones and required more human characters.

21. Foster, Fictions of the Irish Literary Revival, 203.

22. Cf. Harry Levin, introduction to Dubliners, by James Joyce, in The Essential James Joyce (London: Jonathan Cape, 1948), 21: “Not one but many of these sketches might be titled ‘An Encounter.’”

23. Joyce, Dubliners, 29.

24. Ibid., 30.

25. Cf. Levin, introduction, 21: “In calling his original jottings ‘epiphanies,’ Joyce underscored the ironic contrast between the manifestation that dazzled the Magi and the apparitions that manifest themselves on the streets of Dublin; he also suggested that those pathetic and sordid glimpses, to the sentient observer, offer a kind of revelation.”

26. Joyce, Dubliners, 62 (my italics).

27. Ibid., 66 (my italics).

28. Ibid., 73 (my italics).

29. Ibid., 78 (my italics).

30. Ibid., 172 (my italics).

31. Ibid., 174 (my italics).