Learning Objectives for This Chapter

What is the transformation process and value creation?

What is operations and operations management?

What is a supply chain and supply chain management?

Which decisions are within the scope of supply chain and operations management?

Which objectives are used to measure the performance of supply chain and operations management?

Which qualifications should a future supply chain and operations manager obtain?

Which career paths are possible for supply chain and operations managers?

1.1 Introductory Case Study: The Magic Supply Chain and the Best Operations Manager

Santa Claus is one of the best supply chain (SC) and operations managers in the world. He achieves incredible performance: he always delivers the right products to the right place at the right time. This is despite highly uncertain demand and a very complex SC with more than two billion customers.

His strategy and organization is customer-centered and strives to provide maximal satisfaction to children. The organization of his supply chain and operations management (SCOM) is structured as follows. The customer department is responsible for processing all the letters from children all over the world. This demand data is then given to the supply department. The supply department is responsible for buying the desired items from suppliers worldwide. The core of the supply department is the global purchasing team which is responsible for coordinating all the global purchasing activities.

Since many of the children’s wishes are country-specific, the regional purchasing departments (so-called lead buyers) are distributed worldwide and build optimal SC design. In some cases, the desired items are so specific that no supplier can be found. For such cases, Santa Claus has established some globally located production facilities to minimize total transportation costs and to ensure on-time delivery of all the gifts for Christmas.

The customer department regularly analyzes the children’s wishes. They noticed that there are a lot of similar items which are requested each year. In order to reduce purchasing fixed costs and use scale effects, Santa Claus organized a network of warehouses worldwide. Standard items are purchased in large batches and stored. If the actual demand in the current year is lower than forecasted demand, this is not a problem—these items can be used again in the following year. Since there are millions of different items in each warehouse, Santa Claus created optimal layouts and pick-up processes in order to find the necessary items quickly and efficiently.

The SC and operations planning happens as follows. In January, Santa Claus and the customer department start to analyze the previous year’s demand. During the first 6 months of the year, they create a projection of future demand. The basis for such a forecast is statistical analysis of the past and identification of future trends (e.g., new books, films, toys, etc.). After that, the supply department replenishes the items and distributes them to different warehouses. The production department schedules the manufacturing processes. From October, the first letters from children start to arrive. The busy period begins. From October to December, Santa Claus needs many assistants and enlarges the workforce.

Operations and SC execution is now responsible for bringing all the desired items to the children. It comprises many activities: transportation, purchasing, and manufacturing. Children are waiting impatiently to start the incoming goods inspection. No wrong pick-ups and bundles are admissible and no shortage is allowed. More and more, children’s wishes are not about items but rather about events which they want to happen (e.g., holidays, etc.). Service operations are also a competence of Santa Claus. In addition, Santa Claus has established the most sustainable SC in the world using transportation by sledges. Sometimes, letters with very unusual wishes come in the very last moment, but Santa Claus’s SC is prepared for the unpredictable—lastly it is a magic SC.

1.2 Basic Definitions and Decisions

1.2.1 The Transformation Process, Value Creation, and Operations Function

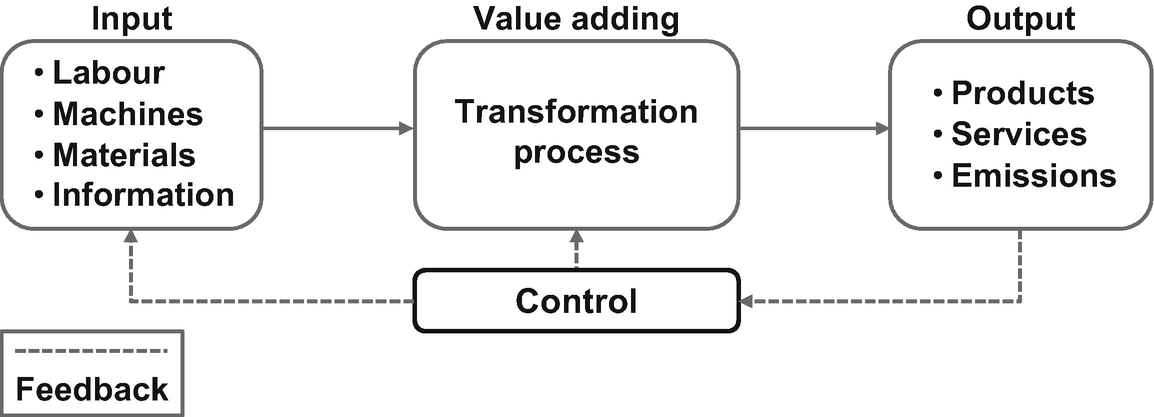

Input-output view of the operations function

The transformation process is the traditional way of thinking about operations management in terms of planning activities. In practice, SC and operations managers spend at least a half of their working time handling uncertainties and risks. That is why the control function becomes more and more important for establishing feedback between the planned and real processes.

One of the basic elements in management is the creation of value added. Identifying the ‘value’ of a product or service means understanding and specifying what the customer is expecting to receive. We usually understand as value added any activity in a process that is essential to deliver the service or product to the customer. Understanding what the customer wants and does not want (to pay) are key aspects in identifying value-added activities. The most effective process is achieved by performing the minimal required number of value-added steps and no waste steps. The reduction of waste and focusing on the value-added activities may increase the efficiency of input resources usage and enable the most effective output of a process. This is the ideal goal that is almost impossible to achieve in practice because of historical development of processes in firms and continuous changes in the firms and markets.

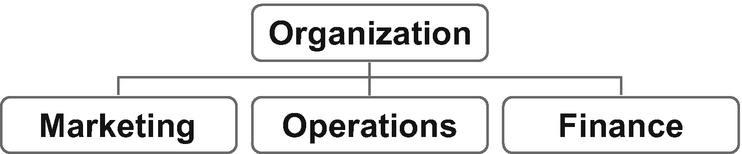

Role of operations in an organization

Operations management is concerned with managing resources to produce and deliver products and services efficiently and effectively.

Operations management deals with the design and management of products, processes, and services, and is comprised of four stages: sourcing, production, distribution, and after sales.

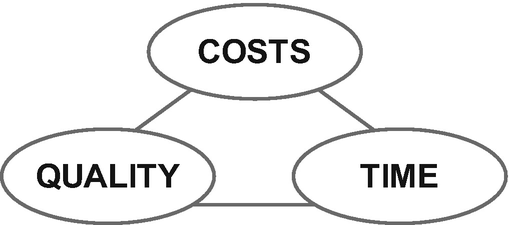

Objectives triangle of operations and supply chain performance

The importance of these objectives is dynamic, i.e., it has changed over time since operations management has a long history. Over the last 60 years, a transition from a producers’ market to a customers’ markets has occurred. This transition began in the 1960s with the increasing role of marketing in conditions of mass production of similar products to an anonymous market. This period is known as the economy of scale. After filling the markets with products, quality problems came to the forefront. In the 1970s, total quality management (TQM) was established.

The increased quality triggered an individualization of customers’ requirements in the 1980s. This was the launching point for the establishment of the economy of the customer. This period is characterized by efforts towards optimal inventory management and a reduction in production cycles.

In the 1980–1990s, handling high product variety challenged operations management. Another trend was the so-called speed effect. The speed of the reaction to market changes and cutting time-to-market became even more important. Consequently, the optimization of internal processes with external links to suppliers was simultaneously rooted in the concepts of lean production and just-in-time (JIT).

Throughout the 1990s, companies concentrated on development approaches to core competencies, outsourcing, innovations, and collaboration. These trends were caused by globalization, advancements in IT, and integration processes in the world economy. Particularly in the 1990s, a paradigm of supply chain management (SCM) was established that has shaped developments in SCOM into the twenty-first century.

From 2010 to 2018, trends such as digitalization, smart operations, predictive analytics, risk management, SC resilience and flexibility, intelligent information technologies, e-operations, leanness and agility, the servitization of manufacturing, outsourcing and globalization, additive manufacturing, and Industry 4.0 shaped the SCOM landscape in practice and research.

1.2.2 Supply Chain Management

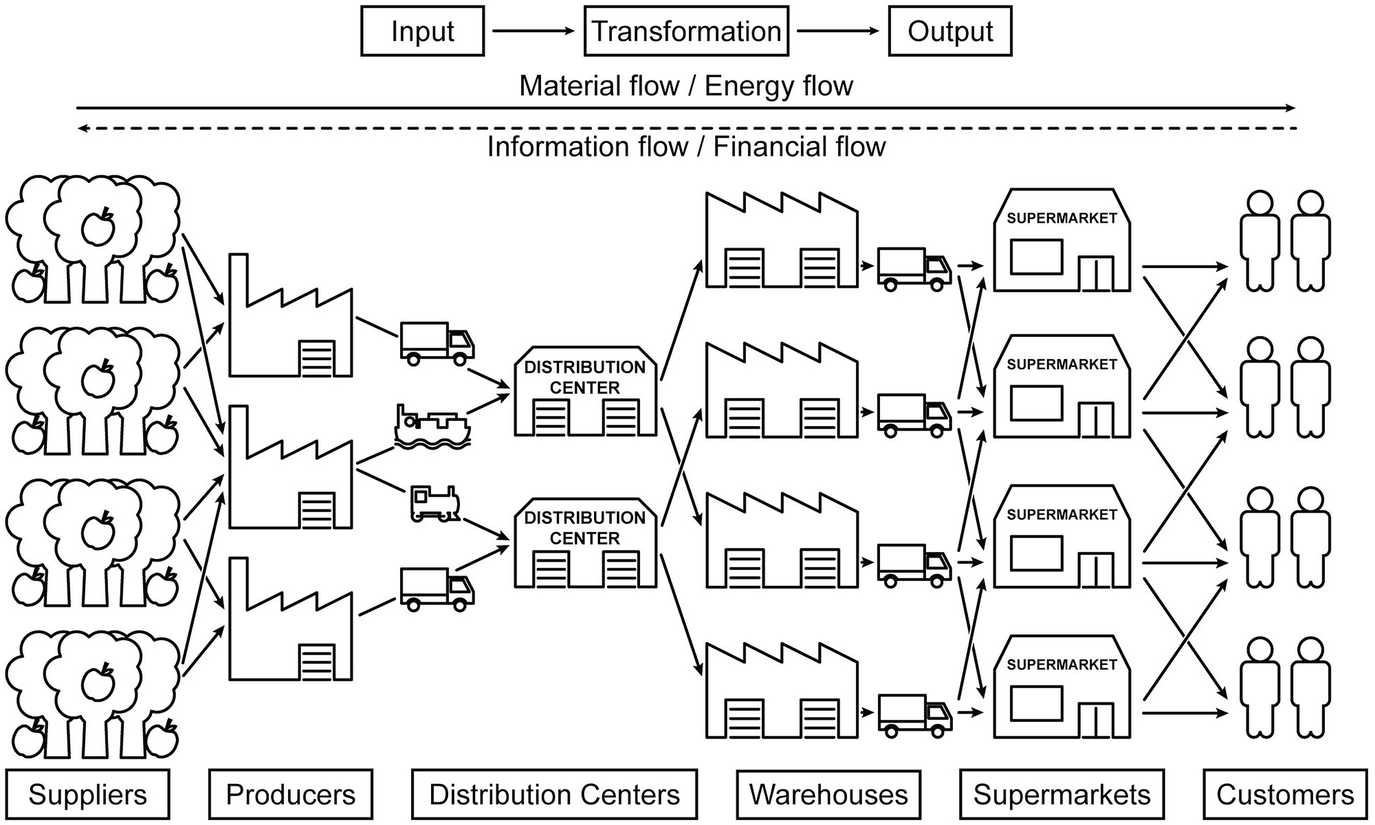

Supply chain

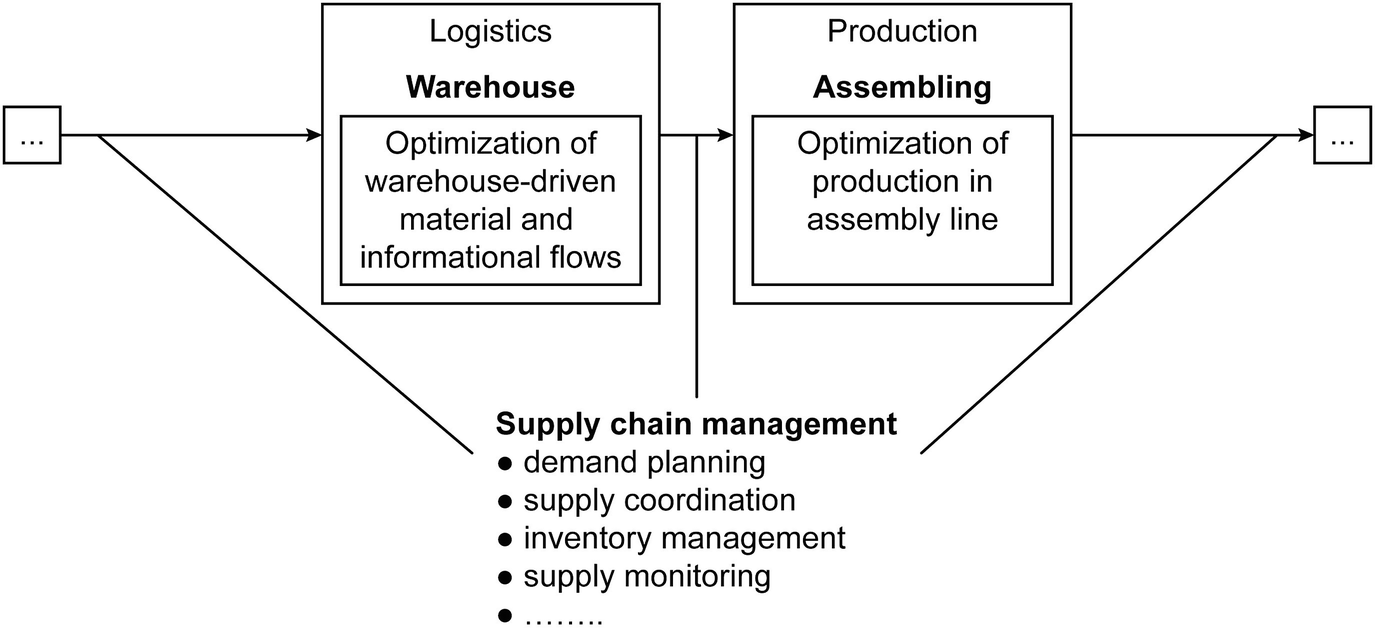

Functions of logistics, production, and SCM in a value chain [from Ivanov and Sokolov (2010)]

SCM integrates production and logistics processes. In practice, production, logistics, and SCM problems interact with each other and are tightly interlinked. Only two decades have passed since enterprise management and organizational structure have been considered from the functional perspective: marketing, research and development, procurement, warehousing, manufacturing, sales, and finance. The development of SCM was driven in the 1990s by three main trends: customer orientation, globalization of markets, and the establishment of an information society. These trends caused changes in the competitive strategies of enterprises and required new value chain management concepts.

The first use of the term “SCM” occurred in the article “SCM: Logistics Catches up with Strategy” by Oliver and Webber (1982). They set out to examine material flows from the raw material suppliers through the SC to the end consumers within an integrated framework that is now called SCM. The origins of SCM can be seen in early works on postponement, system dynamics and the bullwhip effect (Forrester 1961), cooperation (Bowersox 1969), multi-echelon inventory management (Geoffrion and Graves 1974), JIT, and lean production.

SCM, as the term implies, is primarily focused on the inter-organizational level. Another successful application of SCM depends on intra-organizational changes to a very large extent. Even collaborative processes with an extended information system applications are managed by people who work in different departments: marketing, procurement, sales, production, etc. The interests of these departments are usually in conflict with each other. Hence, not only outbound synchronizations, but also internal organizational synchronizations are encompassed by SC organization.

1.2.3 Decisions in Supply Chain and Operations Management

SCOM as a bridge function for matching demand and supply

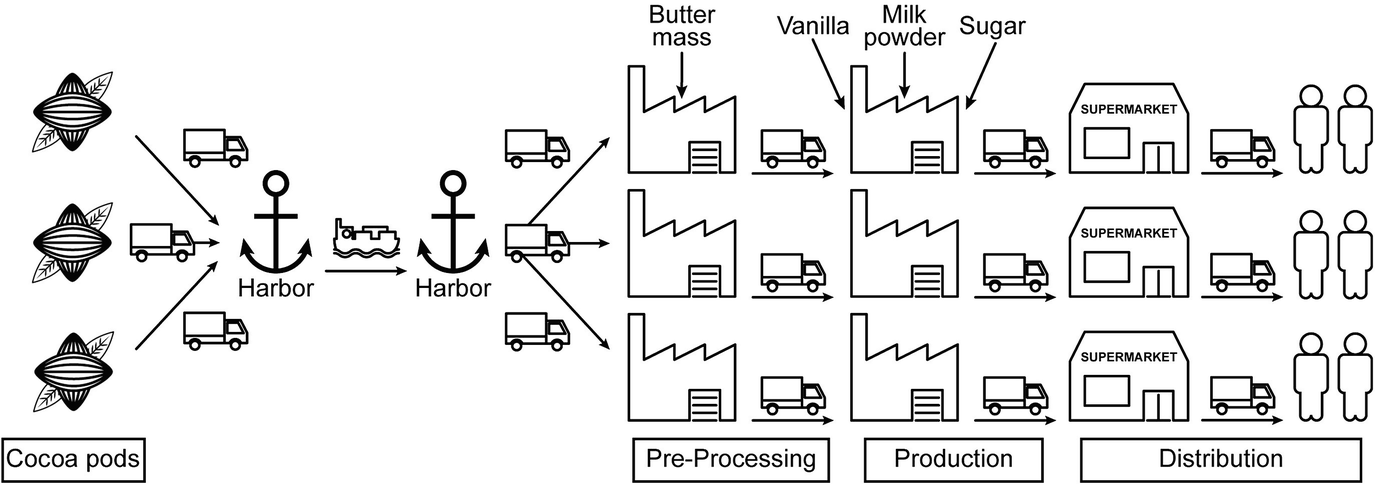

Chocolate supply chain

To produce chocolate, cocoa pods are first harvested from cocoa trees, e.g. in Côte D’ivoire. Cocoa pods are then moved by donkeys to a processing station where they are packed into special carrier bags to avoid damage during transportation by container ship. At the harbor, the bags are packed into special containers and moved to a container ship that will bring them, e.g., to Hamburg.

Along with sugar and milk powder, vanilla is also one of the components needed for chocolate production. Sugar and milk powder are usually sourced locally to avoid long transportation. After unloading at the Hamburg harbor, through which up to 200,000 tons of cocoa pods are shipped each year, the transportation is continued by trucks. Simultaneously, container ships in Guatemala and Madagascar leave the harbor with cargoes full of vanilla.

The cocoa pods are delivered to a preliminary processing plant and separated into cocoa butter and cocoa mass which are then moved in trucks by road to chocolate manufacturers. After getting all the ingredients, a multi-stage manufacturing process is started, the final result of which is chocolate. Chocolate is then packed and delivered in large batches on pallets to distribution centers. From here, small batches are finally delivered to supermarket.

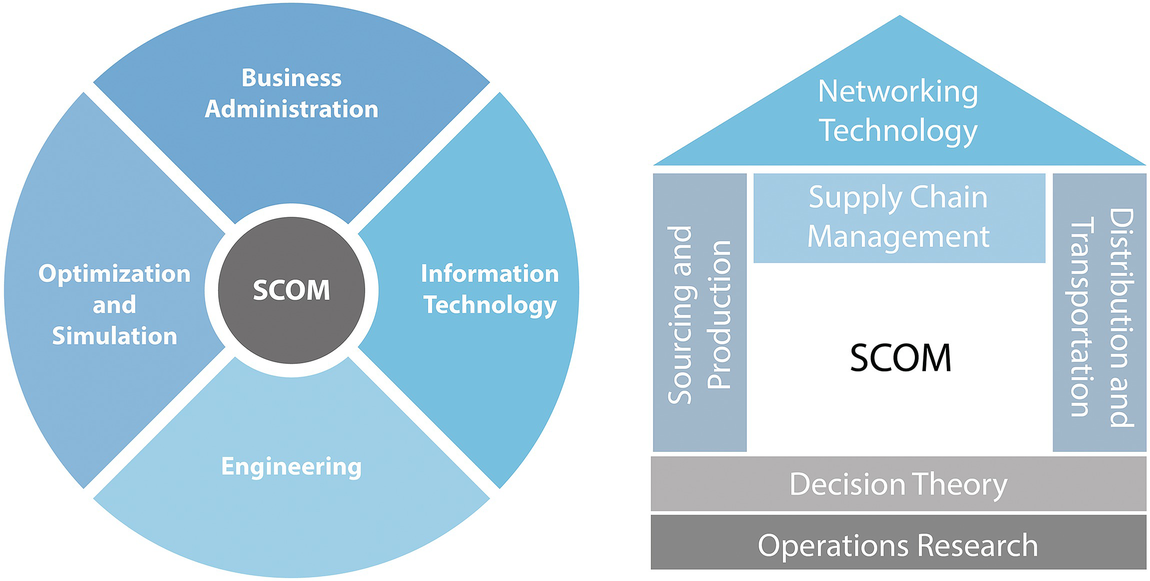

House of SCOM

Decision matrix in supply chain and operations management

This description holds true for many different organizations including global brand manufacturers such as Apple or Toyota, major retailers such as Tesco or Wal-Mart, nonprofit organizations such as International Red Cross, or local petrol stations or hospitals. Purchasing, assembly, shipping, stocking, and even communicating are a few examples of the many different actions unfolding within these organizations, all united by a single purpose: to create value for a customer.

1.3 Careers and Future Challenges in Supply Chain and Operations Management

systems and engineering knowledge

leadership and strong communication skills

general multidisciplinary business knowledge

strong analytical problem solving abilities and quantitative skills

negotiation and presentation skills.

To become an SC or operations manager, it is important to be able to communicate well with people from all departments. There is a strong relationship between the SCOM function and other core and support functions of the organization, such as accounting and finance, product development, human resources, information systems, and marketing functions. Another important skill is time management.

coordinating business processes concerned with the production, pricing, sales, and distribution of products and services

managing workforce, preparing schedules and assigning specific duties

reviewing performance data to measure productivity and other performance indicators

coordinating activities directly related to making products/providing services

planning goods and services to be sold based on forecasts of customer demand

managing the movement of goods into and out of production facilities

locating, selecting, and procuring merchandise for resale, representing management in purchase negotiations

managing inventory and collaborating with suppliers

planning warehouse and store layouts and designing production processes

process selection: design and implement the transformation processes that best meet the needs of the customers and firms

demand forecasting and capacity planning

logistics: managing the movement of goods throughout the SC

risk manager: proactive SC design, risk monitoring, and real-time coordination in the event of disruptions.

SC and operations managers have strategic responsibility, but also control many of the everyday functions of a business or organization. They oversee and manage goods used at the facility such as sales merchandise, inventory, or production materials. SC and operations managers also authorize and approve vendors and contract services at different locations worldwide. Starting positions for SCOM typically include operative responsibilities in procurement or sales departments and work as, for example, a consultant, customer service manager, or a SC analyst. With 5–10 years of practical experience, such positions as purchasing manager, transportation manager, international logistics manager, warehouse operations manager, or SC software manager can be achieved. With 10 or more years of experience, vice president of SCOM is a realistic position.

Operations manager

Business analyst

Production planner

Operations analyst

Materials manager

Quality control specialist

Project manager

Purchasing manager

Industrial production manager

Facility coordinator

Logistics manager

Risk manager.

Plant managers supervise and organize the daily operations of manufacturing plants. For this position, expertise in activities such as production planning, purchasing, and inventory management is needed.

Quality managers aim to ensure that the product or service an organization provides is fit for purpose, consistent, and meets both external and internal requirements. This includes legal compliance and customer expectations. A quality manager, sometimes called a quality assurance manager, coordinates the activities required to meet quality standards. Use of statistical tools is required to monitor all aspects of services, timeliness, and workload management.

Process improvement consultants take over activities which include designing and implementing such activities as lean production, six sigma, and cycle time reduction plans in both service and manufacturing processes.

Analysts are key members of the operations team supporting data management, client reporting, trade processes, and problem resolution. They use analytical and quantitative methods to understand, predict, and improve SC processes.

Production managers are involved in the planning, coordination, and control of manufacturing processes. They ensure that goods and services are produced at the right cost and level of quality.

Service managers plan and direct customer service teams to meet the needs of customers and support company operations.

Sourcing managers are involved with commercial and supplier aspects of product development and sourcing projects. They conduct supplier analysis, evaluate potential suppliers, and manage the overall supplier qualification process, develop and create sourcing plans, manage request for proposals and other sourcing documents, and evaluate and recommend purchasing and sourcing decisions.

International logistics managers work closely with manufacturing, marketing and purchasing to create efficient and effective global SC.

Transportation managers are responsible for the execution, direction, and coordination of transportation. They ensure timely and cost effective transportation of all incoming and outgoing shipments.

Warehouse managers are responsible for managing inventory, avoiding stock-outs, and ensuring material replenishment at minimal costs.

Risk managers analyze possible risks, develop proactive operations and SC design, monitor risks, and coordinate activities for stabilization and recovery in the event of disruption.

Manufacturing companies

Retail establishments

Logistics

Consulting companies

IT companies

Hospitals

Banks and insurance companies

Restaurants

Airlines and airports

Entertainment parks

Building and construction companies

Public transportation companies

Government agencies

Research corporations.

digitalization and smart technologies

globalization and collaboration with suppliers and customers worldwide

risks and resilience

predictive analytics in improving sales, promotions, and forecasting

shorter product lifecycles and fast changing technology, materials, and processes (e.g., additive manufacturing, Internet of Things, and Industry 4.0)

sustainability and mass customization

higher requirements on multidisciplinary knowledge and competencies.

Practical Insights

Excellence in Supply Chain and Operations Management has become a competitive advantage for companies. This requires a new kind of leader for managing complexity, risks, and diversity in global SCs and operations. This textbook provides the strategic, management and analytical skills you need to launch your international career in global SCM, operations, and logistics. Three pillars build the textbook framework: practical orientation and creation of working knowledge, methodical focus, and personal development of students the development of advanced communication, interaction, and organizational skills with the help of case studies and business simulation games.

A career in SCOM opens the door to many opportunities. The job itself is diverse, because of the variety of tasks completed by SC and operations managers. Another advantage is the high income expected, especially for experienced SC and operations managers. On the other hand, there may be long working hours and stress. Operations and SC managers generally have to work in a changing environment, so they have to be flexible. As can be observed in the real job offers, flexible managers with a willingness to travel a lot are always in demand.

Example

Jeff Williams is Apple’s Senior Vice-President of Operations

Jeff leads a team of people from around the world who are responsible for end-to-end supply chain management and are dedicated to ensuring that Apple products meet the highest standards of quality. Jeff joined Apple in 1998 as head of worldwide procurement, and in 2004 he was named vice-president of operations. In 2007, Jeff played a significant role in Apple’s entry into the mobile phone market with the launch of the iPhone, and he has led worldwide operations for iPod and iPhone since that time. Prior to Apple, Jeff worked for the IBM Corporation from 1985 to 1998 in operations and engineering roles. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering from North Carolina State University and an MBA from Duke University.

Source: https://www.apple.com/pr/bios/jeff-williams.html

1.4 Key Points

Operations is a function or system that transforms inputs into outputs of greater value. Operations management is involved with managing resources in order to produce and deliver products and services. It includes the stages of sourcing, production, distribution, and after sales. A supply chain is the network of organizations and processes along the entire value chain. SCM is a collaborative philosophy and a set of methods and tools for integrating and coordinating local logistics processes and their links with production processes from the perspective of the entire value chain and its total performance.

SCOM is everywhere: in production, logistics, healthcare, airlines, entertainment parks, passenger transport, hotels, building and construction, etc. Key objectives of SCOM are costs, time, quality, and resilience. A career is SCOM is multi-faceted and requires multidisciplinary knowledge that are comprised of elements from business administration, optimization, engineering, and information systems. Examples include logistics problems, warehouse management, transportation optimization, procurement quantity optimization, inventory management, cross-docking design, intermodal terminals design, etc. Accordingly, production management deals with optimizations in assembly lines, production cells, etc. SCM problems include supply chain design, demand planning, and supply coordination.