Railroad Stations: San Pedro: Pacific Electric Ry. and Southern Pacific R.R., 5th St. and Harbor Blvd. Terminal Island: Union Pacific and Santa Fe R.R. Wilmington: Santa Fe Ry., 711 E. Anaheim St.; Southern Pacific R.R., 331 N. Avalon Blvd.; Pacific Electric Ry., 333 N. Avalon Blvd. 2 Pacific Electric Ry. lines between San Pedro and Los Angeles, one via Dominguez Junction, the other via Gardena. Harbor Belt Line links all rail and steamship lines.

Bus Stations: San Pedro: Union Bus Depot, 240 W. 6th St., Wilmington: Los Angels Motor Coach Corp., 104 E. Anaheim St.; Wilmington Bus Co., 1541 Bay View Ave.

Streetcars: Local service in San Pedro and Wilmington by Pacific Electric Ry., fare 6¢.

Taxis: Several companies; rates under zone system, minimum charge 15¢.

Information Bureaus: San Pedro: Chamber of Commerce, 820 S. Commercial St.; Automobile Club of Southern California, 1432 S. Pacific Ave. Wilmington: Chamber of Commerce, 327 Avalon Blvd.

Streets and Numbers: San Pedro: from 1st St. S. all E.-W. streets are numbered to Paseo del Mar; N. from 1st St. E.-W. streets bear names, as do all N.-S. streets. The principal N.-S. thoroughfare is Pacific Ave. Chief E.-W. route is 6th St., from Waterfront to Pacific Ave., then S. to 9th S. Wilmington: Streets laid out in squares except those skirting the water front. E.-W. streets are lettered from A to R; avenues run N.-S. Exceptions are Pacific Coast Hwy. and Anaheim St. (E.-W.), and Avalon and Wilmington Blvds. (N.-S.).

Hotels and Apartment Houses: San Pedro: 7 first-class hotels. Wilmington: 4 hotels. Numerous small hotels, tourist camps, apartments, and flats.

Churches: San Pedro: 18 churches and 22 miscellaneous religious groups. Wilmington: 11 churches and 8 miscellaneous groups.

Public Schools: San Pedro 13, Wilmington 5.

Motion-Picture Houses: San Pedro 5, Wilmington 2.

Parks, Playgrounds and Picnic Grounds: (See also Los Angeles General Information.) San Pedro: Alma, 21st and Meyler Sts,; Averill, Dodson Ave. and Averill Dr.; Leland, Upland and Cabrillo Aves.; Peck, Summerland Ave. and Patton St.; the Plaza, between Beacon St. and Harbor Blvd., from 6th to 16th Sts.; Point Fermin, end of Paseo del Mar and Gaffey St. Wilmington: Banning, bounded by M and O Sts., Eubank and Lakme Aves.

Daily Newspapers: News Pilot (San Pedro); Journal and Press (Wilmington), daily, except Sun.

Athletic Fields: San Pedro: Navy Field, 34th St. and Pacific Ave., 3 football fields and 8 baseball diamonds; Sports Field, foot of Pacific Ave., football, baseball, tennis, and softball; Daniels Field, 12th and Gaffey Sts., lighted for night baseball and football.

Boating and Yachting: Anchorages in Watchorn Basin, reached by 22nd and Miner Sts. (San Pedro). California Yacht Club, Yacht St. at water front (Wilmington). Other anchorages along West Basin and other points.

Boxing and Wrestling: San Pedro: Army and Navy Y.M.C.A., 921 S. Beacon St. Wilmington: Wilmington Bowl, 909 Mahar St.

Fishing: San Pedro: Shore fishing from breakwater, fishing barges offshore, reached by water taxis, rates $1 including transportation, tackle and bait; charter boats, including live bait and tackle, $35 per trip; two 65-foot launches, equipped for deep-sea fishing, from Pier 124 (May 1 to Oct. 1), fee $2; license for game fishing, residents, $2, nonresidents, $3. Wilmington: live-bait boats from water front for fishing banks off Santa Catalina Island; barges anchored offshore, reached by water taxis; fishing from piers.

Football: San Pedro: High School field, 1221 S. Gaffey St. Wilmington: Phineas Banning High School, 1500 N. Avalon Blvd.

Soccer: San Pedro: 1527 Mesa St., Leland and 22nd St., 3333 Kerckhoff Ave., 1530 W. 7th St. and 1221 S. Gaffey St. Wilmington: 1140 Mahar Ave.

Golf: Royal Palms course (San Pedro), at White Point, 18 holes, open to public. Fees, 35¢ weekdays, 50¢ Sun.

Softball: San Pedro: 828 S. Mesa St., 429 Stephen M. White Dr., 1221 S. Gaffey St. Wilmington: 1331 Eubank St., 1301 Fries Ave., 1196 Gulf St., 1500 N. Avalon Blvd.

Swimming: Cabrillo Beach (San Pedro), landward end of the breakwater, surf and still water. Surf bathing (Wilmington).

Tennis: San Pedro: Peck Park, Summerland Ave. and Patton St., 4 courts, lighted for night playing; Municipal Playground, 828 Mesa St., 2 courts. Wilmington: 2 courts at 1500 N. Avalon Blvd.

Note: Information concerning Steamship Berths and Traffic Regulations, see Los Angeles General Information.

Unlike many great world cities, Los Angeles is not situated directly on either a navigable river or the sea. Its great modern harbor, with its 25-mile frontage, was created by dredging the mud flats and salt marshes of San Pedro Bay, 25 miles south of the heart of the city. Since 1920 the Federal government and the city of Los Angeles have spent $60,000,000 in deepening channels, building breakwaters, and making other improvements. Today, the harbor is the Pacific base of the U.S. Fleet and one of the nation’s five great ports, frequented by thousands of chunky freighters, trim passenger ships, and fishing vessels of many kinds. In 1938 some 5,700 large ships tied up at its piers and wharves to discharge and load cargoes valued at a billion dollars; oil products and manufactures constituted most of the export trade; raw and semi-raw materials for use of industry comprised 75 per cent of the imports.

The two harbor communities of SAN PEDRO (90 alt., 46,685 pop.), and WILMINGTON (25 alt., 13,946 pop.), originally known as New San Pedro, were independent cities until 1909 when they were absorbed by Los Angeles, which organized a Harbor District governed by a board of five commissioners, appointed by the mayor. This board manages the muncipal port facilities, which comprise 95 per cent of those in the harbor. On the west the harbor is protected by the San Pedro Hills and Point Fermin, from which extends a long breakwater, in two sections, protecting it on the south and east. The opening between the two sections, marked by the Breakwater Lighthouse, provides passage into the Outer Harbor. Here the U.S. Battle Fleet (see Long Beach), with tenders and supply, repair, and hospital ships, rides at anchor for many months of the year. Between San Pedro and Terminal Island a deep channel leads into the Inner Harbor, where ships are manoeuvered in the large turning basin and warped into the slips and docks that, like saw teeth, jut out from the water front at Wilmington, four miles inland, the port’s chief freight and passenger terminal. On Terminal Island, a man-made improvement, are large docks, boat-building and repair yards, and colorful Fish Harbor. East of the island, Cerritos Channel leads to the Inner Harbor of Long Beach (see Long Beach).

A bustling port, notwithstanding its somewhat somnolent air, San Pedro is the older, larger, and more colorful of the two communities. Along the water front are faded brick buildings of the first decade of the century; the residential district spreads back up the hills known as the Palos Verdes (green woods). Stores along the front streets display nautical gear of every kind—denim jackets, duffle bags, sheath knives, spyglasses, and gargantuan dice. Here are tattoo parlors, “wing-ding joints,” semi-secret gambling dives where sailors challenge fortune at cards, roulette, fan-tan, and almost any other game. Everywhere are union halls and posters, for the water front is strongly unionized and thoroughly conscious of its strength. The numerous bars are distinctive in character and name. In an erstwhile bank old salts, and young, straddle stools of steel tube before white marble counters as the “banker” replenishes his stocks from the vaults, where he keeps his liquid assets, often more negotiable than other kinds of bonded stuff. The Silver Dollar saloon has murals by a Chinese who, on completing them, shot himself. Whispering Joe’s, Shanghai Red’s, and Scuttle Butt Inn are popular. At Goodfellow’s huge Scandinavian seamen dance solemnly with one another to wheezy tunes played on an accordion. The maritime workers of San Pedro include Japanese, Jugoslavs, Czechs, Italians, Portuguese, Mexicans, and Scandinavians; the last are the largest group, but these grandsons of the men who sailed the Seven Seas in the days of the old square-riggers have so intermarried with other groups that racially they are now scarcely distinguishable.

South of the Pacific Electric Line’s interurban depot, a low gray structure with arcades, through which flows a ceaseless tide of eager tourists and blase wanderers, are fish wharves; beyond are old sun-blistered, pumpkin-yellow buildings, once a station and wharf, at present abandoned to two battered South Sea trading schooners. Nearby, lumberyards occupy a strip of sand known as “Mexican Beach,” the hangout of beachcombers and swimmers. Here is “Mexican Hollywood,” a collection of shacks, periodically the scene of much nocturnal revelry, and “Happy Valley,” home of seamen between voyages to distant ports.

San Pedro has long talked of the sea and its lore, and old tars tell and retell tales of dope-running, rum-running, alien-smuggling, spy scares, police and gang raids on gambling dens operated on barges offshore, weird murders on yachts bound for the “isles of somewhere,” buried treasure, such mysterious vanishings as that of the Belle Isle off the Galapagos in 1935, and many a shipwreck since the day in 1828 when a “Santa Ana” blew the brig Danube ashore here, the first to be piled up in the harbor.

Wilmington, an offshoot of San Pedro, has had a less colorful and more businesslike career. Established to handle heavy freight, it still serves that function. Ocean-going ships tie up here to discharge and take on goods and passengers. Around the wharves and piers are streets lined with shipping offices and warehouses storing goods from all parts of the world.

The recorded history of the area dates back to 1542, when Cabrillo sailed his leaky little craft into the harbor, which he named La Bahia de los Fumos (bay of smokes), for the Indian fires on the slopes of Palos Verdes. A map maker years later identified it as La Bahia de San Pedro to commemorate Vizcaino’s arrival on November 26, 1602, the feast day of St. Peter. During the closing years of the 18th century Spanish rancheros shipped produce from the bay. In 1808 Captain William Shaler, a fur trader, sailed in with the first Yankee ship, Lelia Byrd, and although trade with foreigners was forbidden by the authorities, Yankee skippers continued to come, for the rancheros and even the padres were anxious to trade hides and tallow for manufactured goods.

A description of the harbor in 1838 has been left us by Richard Henry Dana in his Two Years Before the Mast: “ . . . there was no sign of a town. What had brought us into such a place we could not conceive . . . we lay exposed to every wind that could blow. I learned to my surprise that the desolate looking place was the best place on the whole coast . . . and about thirty miles in the interior . . . was the Pueblo de Los Angeles.” San Pedro had developed somewhat when Major Horace Bell wrote in 1853 that it was a “great place; it had no streets, for none were necessary. There were two mud scows, a ship’s anchor and a fishing boat . . . broken down Mexican carts, a house, a large haystack and a mule corral.” When Dana returned in 1859 he found a wharf, two or three warehouses, and a stagecoach, which plied daily between the port and the pueblo.

The early development of the harbor was in large part the work of Phineas Banning, who came to California in 1851 and soon established freighting service between San Pedro and the pueblo. To gain an advantage over his one competitor, he bought part of the old Rancho San Pedro on the inner bay, closer to Los Angeles, and there built a wharf and warehouse, founding what was known as New San Pedro in 1858. A gale hastened its development, for it wrecked Banning’s wharf at San Pedro and he transferred all his activities to the new port. Every day Banning, wearing red suspenders, labored at the wharf and his booming voice dispatched an increasing number of carts and coaches up the dusty road to the pueblo. For a few years New San Pedro surpassed its parent port both in population and tonnage handled. During the Civil War the United States Army quartered troops in the town, and in 1863, when its population of soldiers and civilians approximated 6,000, the State legislature renamed the town for Wilmington, Del., Banning’s birthplace. In 1868 a railroad was built to Los Angeles, but the following year the Southern Pacific purchased the road and extended it to San Pedro. Coastwise vessels thus could load from “ship to car,” and San Pedro regained its ascendancy, although the coming of the railroads and the growth of population brought commerce enough to make both ports prosperous. Wilmington was incorporated as a city in 1872; San Pedro, in 1888.

The development of tremendous man-made Los Angeles Harbor from mud flats and salt marshes is a dramatic story. In 1858 small steamers and sailing vessels from San Francisco and South America anchored offshore while their cargo was discharged into lighters. Banning dredged the inner harbor, by a crude system of two boats and rakes, which were dragged along the bottom of the channel, loosening silt, which the tide carried out to sea. But in spite of this work and the dredging of the San Pedro main channel to a depth of 16 feet in 1871, the port remained a shallow basin with little protection from the sea. The Federal government completed a jetty between Terminal Island (then Rattlesnake Island) and Dead Man’s Island in 1893, but a bitter controversy developed as to whether a harbor should be constructed here or at Santa Monica (see Pueblo to Metropolis). U.S. Senator Stephen M. White, “father” of the harbor, overcame opposition in Washington, and the first rock of the new breakwater was dumped off Point Fermin in 1899. At the turn of the century the port was handling 200,000 tons a year, a four-fold increase since 1871, and two railroads had terminals at the harbor. Increased business and harbor facilities brought the two ports together, and in 1909 they were annexed by Los Angeles and consolidated as the Harbor District. Today, Los Angeles is one of our five largest seaports.

During recent years the harbor has been involved in the struggle along the Pacific between maritime unions and shipowners. A 100-day strike in 1937 achieved substantial gains for labor and unification of the unions under the leadership of the militant longshoremen’s union, which led most of the maritime unions into the Congress of Industrial Organization. Fishermen have likewise unionized themselves both in the CIO and the American Federation of Labor, and a close bond now unites fishermen, longshoremen, seamen, marine engineers, bartenders, and all engaged in wresting a livelihood from their common friend and enemy, the sea.

SAN PEDRO

The CIVIC CENTER, Harbor Blvd. and Beacon, 6th and 9th Sts., lies on the west side of the Main Channel. Its buildings are grouped about the northern end of the tree-studded Plaza, which extends southward to 13th Street. The Plaza offers a good view of the 1,000-foot MAIN CHANNEL between San Pedro and Terminal Island shore lines, which leads from the Outer Harbor to a 1,600-foot turning basin bounded by Smith’s, Mormon, and Terminal Islands. At the turning basin the channel branches to the West and East basins of the Inner Harbor.

1. Dominating the Civic Center, at its northeast corner, is the six-story, tan-brick BRANCH CITY HALL, 638 S. Beacon St., built in 1928 to house the Harbor Department offices and various branch units of the Los Angeles municipal government.

2. The new UNITED STATES CUSTOMS HOUSE AND POST OFFICE, Beacon and 9th Sts., a three-story, reinforced-concrete structure completed in 1935, faces the park on the west side. In the lobby is a 40-foot mural by Fletcher Martin, depicting the evolution in the transportation of mail in various parts of the country. The post office and various Federal bureaus are quartered in this building.

3. The UNITED STATES IMMIGRATION STATION (open 9-4:30), foot of 22nd St., is a two-story building of gray stucco, with barred windows and an adjoining “bull pen,” through which annually pass 15,000 aliens, 60 per cent of whom are Orientals.

4. The MARINE EXCHANGE LOOKOUT STATION (not open), on the roof of the six-story Municipal Warehouse No. 1, Pier No. 1, foot of Signal St., is a square glass-enclosed compartment equipped with a powerful telescope by which ships are identified an hour before they arrive at Breakwater Light. Flag signals are used to communicate with ships during the day; a blinker-light system is employed at night.

5. At the tip of Pier No. 1, within full view of Outer Harbor ship traffic, is the two-story cement building of the PILOT STATION (not open), headquarters of pilots skilled in navigating the Inner Harbor.

6. At the U.S. NAVY LANDING, 22nd St. at the head of East Channel, officers and men from the warships land in gigs and longboats for shore leave; visitors embark here for the dreadnaughts and cruisers anchored in the Outer Harbor (Sun. and holidays only, 1-4; transportation free).

The 450-foot U.S. COAST GUARD PIER, foot of Outer St., in Watchorn Basin, is the headquarters of the local unit of the Coast Guard, which has a force of 150 officers and men, two 165-foot patrol boats, and five smaller craft; the unit patrols the coast from the Mexican border to Point Buchon, north of Santa Barbara. Its gray patrol boats, Aurora and Hermes, carry three guns each, mounted on the main deck, are equipped with powerful searchlights and radio transmitters, and fly the red-barred Coast Guard flag with its motto, Semper Paratus (L., always ready). When planes are needed for an emergency, such as removing a sick or injured person from a vessel at sea, a call is made on the air base at San Diego, also part of the southern California section, for one of its five amphibian planes. Coast Guard activities here, once chiefly concerned with rum-running, now center on the preservation of life and property and the enforcement of customs and navigation laws.

FORT MacARTHUR, LOWER RESERVATION (open, except during artillery practice), 244 acres set aside in 1916 and named in honor of General Douglas MacArthur, former military governor of the Philippine Islands, lies on a bluff overlooking West Channel and Outer Harbor. Ranged around three sides of the five-acre parade ground are stucco and frame bungalows occupied by officers of the 63rd Coast Artillery (anti-aircraft) and the Third Coast Artillery. Barracks for enlisted men, the commissary and supply departments, mess halls and garages are massed along the east side. The garrison ranges from 700 to 800 officers and men. In the reservation are two 14-inch guns weighing 365 tons each; mounted on railway carriages, they are 21 feet high, 95 feet long, and fire steel 1,560-pound projectiles at a muzzle velocity of 2,700 feet per second—over 30 miles per minute.

POINTS OF INTEREST

San Pedro

Wilmington

CABRILLO BEACH PARK, foot of Stephen M. White Dr. (open 6 a.m. to midnight), named in honor of Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, is a recreational area with beach, park, and playground facilities.

7. A nine-foot concrete monolithic STATUE OF CABRILLO is the central piece of a circular landscaped plaza in the park.

8. A white stucco BATHHOUSE (rates, 10¢-25¢), is at the right of the statue. In the seaward chambers of the building is the CABRILLO BEACH MUSEUM (open 9-5; free), a municipal institution exhibiting specimens of marine and shore life along the Pacific coast.

9. A stucco BOATHOUSE left of the bathhouse, with a wooden pier for small craft, maintains boat service to an offshore fishing barge (rates vary).

The U. S. GOVERNMENT BREAKWATER extends in two detached sections from the tip of the San Pedro headland at Cabrillo Beach to a point opposite the mouth of the Los Angeles Flood Control Channel, a distance of almost five miles. The curving 11,000-foot section between Cabrillo Beach and Breakwater Light was begun in 1899 and completed in 1912 at a cost of $3,000,000. The second section, a continuation of the first, cost $5,600,000. Both sections consist of rock fill almost 200 feet wide at the base, tapering to a width of 20 feet at the top, which stands 14 feet above the sea at low tide. At the seaward end of the first section is Breakwater Light, built in 1913, having a 110,000 candlepower beam visible 14 miles.

POINT FERMIN PARK, extending (R) along Paseo del Mar (driveway along the sea), a 28-acre expanse of tree-shaded lawns on the rugged bluffs of Point Fermin, has sheltered pergolas, a promenade along the edge of the palisade, and a picnic ground. The park, acquired in 1923, bears the name of Point Fermin, which was so-named in 1784 for Padre Fermin Francisco Lasuen, who succeeded to the presidency of the California missions on the death of Padre Junipero Serra.

10. The old GOVERNMENT LIGHTHOUSE on the point, built in 1874 and still in use, throws a 6,000 candlepower beam visible for 18 miles.

The 176-acre FORT MacARTHUR UPPER RESERVATION (not open), on the rolling seaward slopes of the Palos Verdes Hills behind Paseo del Mar, and Gaffey St., was acquired between 1910 and 1921 as a site for modern fortifications in the harbor defense program. Within the enclosing wire fence, concealed behind low hills, are massive guns, their number and caliber guarded as military secrets. Along the Gaffey Street side are barracks, supply houses, and garages.

11. The LOS ANGELES SHIPBUILDING AND DRYDOCK CORPORATION PLANT (adm. by arrangement), West Basin north of the San Pedro business district, includes a floating drydock with a lifting capacity of 12,000 tons, shipyards, wharves for ship repair, and facilities for the construction and repair of all types of vessels.

12. The OLD GOVERNMENT SUPPLY WAREHOUSE (not open), Fries Ave. and A St., the oldest building in Wilmington, is a huge barnlike structure of shiplap construction, held together by square handmade nails; the roof ridge is topped with three square cupolas. Built in 1858, when Drum Barracks was still a tent camp, the warehouse was used to store supplies consigned to Army posts.

13. From the huge concrete and corrugated iron SANTA CATA-LINA ISLAND TERMINAL, foot of Avalon Blvd., ships annually carry between 500,000 and 650,000 pleasure seekers to Santa Catalina Island (see Tour 5A). The landing for hydroplanes to Santa Catalina Island is at the head of Slip 5, west of the ship terminal.

14. At the entrance to DRUM BARRACKS, 1053-55 Cary Ave. (open by arrangement), a cypress archway is inscribed “Officers Quarters 1862-68, U.S. Army Supply Depot for Southern California, Arizona and New Mexico, U.S. Department of the Southwest.” The white building is covered with vines and surrounded by palms, cypress, and pepper trees. The main building and two rearward wings contain 14 rooms; those in front have high ceilings in the stately manner of the 1860’s. The barracks, the second oldest building in Wilmington, was constructed from timbers cut at the Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Navy Yard in 1861, shipped around Cape Horn, and raised by army men in 1862 on a 40-acre site acquired by the Government from Phineas Banning for one dollar. In a rear patio, bright with greenery, is an old ivy-covered well with mossy rope and oaken bucket; the well has been transformed into a shallow goldfish pond.

The barracks, named for General Richard Colton Drum, whose son, General Hugh Drum, planned the military fortifications in Hawaii, were built both as a base for operations against the Indians and to overawe the Secessionist movement in southern California. Here was the terminus of the first telegraph in the Southwest, and of the Government’s short-lived camel service (see Tour 2), between the barracks and Tucson, Arizona. During the early years of the Civil War, between 200 and 400 soldiers were quartered here. With the subjugation of the Indians in the late 1860’s the barracks were abandoned and the land returned to Banning. The remaining building is now a private residence.

BANNING PARK, M and O Sts., Eubank and Lakme Aves., perpetuates the memory of Phineas Banning. The 20-acre tract, acquired in 1927 from the Banning heirs, retains its quiet old-fashioned charm, with its white picket fence and tree-lined walks.

15. The old GENERAL BANNING HOUSE (not open), in the park, is a white three-story, 18-room mansion, with a two-story portico. The mansion, still sturdy and well-preserved, has been a landmark in the harbor district for more than half a century. To the rear is a frame stable and carriage house, with a collection of surreys, buggies, and carriages, and a stagecoach that saw service in Banning’s California Stage Company. An old brick reservoir, 50 feet in diameter, west of the mansion, has been converted into a picnic ground. Used for storing water in the Spanish rancho days, its circular brick wall has been fitted with windows and doors, and the interior, open to the sky, has a pergola supporting bougainvillaea and other vines. A stream meanders through the park, widening at places into small lagoons. On the playground to the east are softball, tennis, basketball, and horseshoe courts, a gymnasium, a children’s playfield, and an auditorium with a dance floor.

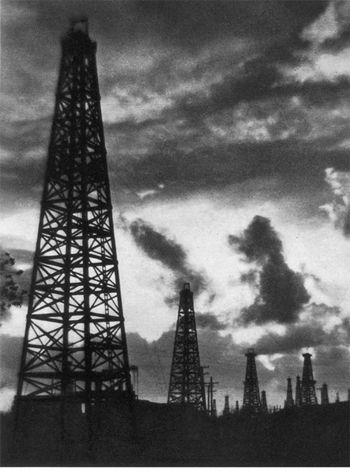

The derricks of the WILMINGTON OIL FIELD, scattered throughout the Wilmington residential district from O Street on the north to Fries Avenue on the west, become a veritable forest of rigs on either side of Henry Ford Avenue, south of Anaheim Street. In July 1938 the field had 483 producing wells, with a combined yield of 95,000 barrels per day. The discovery well was spudded in April 26, 1936.

16. The FORD MOTOR COMPANY ASSEMBLY PLANT (open by arrangement), 700 Henry Ford Ave., lies on reclaimed marshland athwart the Los Angeles-Long Beach boundary line, and assembles automobiles and manufactures parts. At capacity production the plant assembles 400 cars daily and employs 2,500 men.

17. The 270-foot CERRITOS CHANNEL DRAWBRIDGE, of the counterpoised or bascule type, foot of Henry Ford Avenue, is the only bridge to Terminal Island.

TERMINAL ISLAND, reached also by ferries from San Pedro, foot of Terminal Way (5¢; 25¢ per car, 5¢ per passenger), is largely man-made, representing an investment of $12,000,000. Six miles long, from one-half to three-quarters of a mile wide, the island is lined along the Inner Harbor and part of the Outer Harbor shore with docks, wharves, slips, factories, oil plants, a Federal prison, and offices. Its western two-thirds lie in Los Angeles; the eastern third, in Long Beach

18. The SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA EDISON COMPANY STEAM PLANT (open by arrangement weekdays 8-3), on a 43-acre tract at the east end of Terminal Island, consists of three white concrete buildings with slender concrete stacks, the highest rising 262 feet. Gigantic boilers burning natural gas piped from the Kettle-man Hills 215 miles distant convert 20 tons of water into steam every minute. The towers carrying the high voltage cables across Cerritos Channel are 310 feet high, overtopping all structures in the harbor.

The new U.S. FLEET AIR BASE (adm. by arrangement), Seaside Avenue to the edge of the Outer Harbor, includes a concrete seaplane haul-out ramp, planes, a landing and tender wharf, a dredged seaplane anchorage protected by an 1,800-foot rock jetty, two runways for land planes, and a corrugated iron hangar, the first of several to be built. There are also men’s dormitories, mess halls, officers’ quarters, quartermaster and administration buildings.

19. The MARINE METEOROLOGICAL OBSERVATORY (not open), at the E. end of Cannery St., operated jointly by the Los Angeles Harbor Department and the California Institute of Technology (see Pasadena) on a 24-hour schedule, issues storm warnings and weather data to mariners. Through its associate staff of students and scientists from the California Institute of Technology, it conducts research in meteorology, aerology, climatology, oceanography, modern weather forecasting, and fog studies. The U.S. Navy uses its findings in making weather maps for use of airplane pilots.

FISH HARBOR, an artificial inlet on the south side of Terminal Island, protected by inner and outer moles, is the center of Los Angeles’ fishing and canning industry yielding $20,000,000 of products annually. Three sides of the little harbor’s quadrangular shore are crowded with canneries, boatyards, fertilizer plants, gasoline filling stations for tuna clippers, and other establishments auxiliary to fishing and canning. The annual pack is valued at $15,000,000; such by-products as fish oil and meal, fertilizer, and pet foods add an additional $5,000,000.

Fish Harbor is the home port of 1,200 fishing boats. Approximately 300 are operated by Japanese, and the remainder by Slavonians, Italians, Portuguese, Norwegians, and Americans. Fleets of Monterey trawlers leave daily and return at dusk with the day’s catch. The tuna clippers, equipped with deep wells, live-bait tanks, and Diesel engines, go as far afield as the South Seas.

Ten packing plants, with approximately 3,000 employees, operate in the harbor district. Tuna, albacore, yellowfin, bluefin, skipjack, sardines, mackerel, and other fish are tossed into traveling baskets, which dump them on conveyor belts leading into the canneries. Men of many nations carry on the work in hip boots, sweaters, and knitted caps.

Slavonians, who represent about one-third of the fishermen, live mainly in San Pedro. The Japanese, Italians, Portuguese, and Filipinos, numbering some 2,000, have gathered in a colony of their own on the north shore of Fish Harbor immediately behind the wharves and extending the width of the basin and north from Wharf Street to Terminal Way. The section is criss-crossed with narrow streets bearing such names as Barracuda, Tuna, Shrimp, Bass, and Sardine. On them is heard a babble of many tongues, but seldom English. In the yards of the frame cottages and along the water front, men, women, and sometimes children squat mending fish nets, some of which are 3,000 feet long and valued at $5,000.

The Japanese population numbers approximately 600 fishermen, 150 merchants, about 500 women, and an equal number of children. It forms a closely-knit colony, having its own Fishermen’s Association.

20. The 38-acre BETHLEHEM SHIPBUILDING CORPORATION PLANT (open by arrangement), 905 S. Seaside Ave., is equipped to recondition and repair all sizes and types of ships. Its floating drydock, with a lifting capacity of 15,000 tons, is the largest in southern California.

21. The new FEDERAL REGIONAL PENITENTIARY (adm. by arrangement), the Government’s newest West Coast prison for short-term offenders, occupies the seaward side of the Terminal Island section known as Reservation Point. Completed in May 1938, the $1,380,000 institution is of reinforced concrete, with three cell blocks and nine dormitories, providing quarters for 600 male and 24 female prisoners. The cell blocks, dormitories, machine shops, mess hall, quarantine and administration building, and auditorium surround a quadrangular exercise yard.

UNLOADING TUNA FISH, FISH HARBOR, TERMINAL ISLAND

Burton O. Burt

Bret Weston

Bret Weston

F. W. Carter

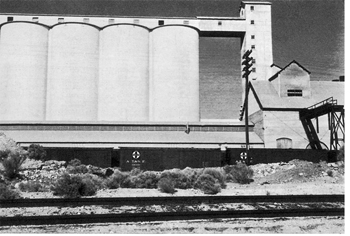

AIRVIEW OF INDUSTRIAL SECTION, LOS ANGELES

Spense Air Photos

Los Angeles County Chamber of Commerce

WINE EXPERTS TASTE AND CLASSIFY CALIFORNIA VINTAGES

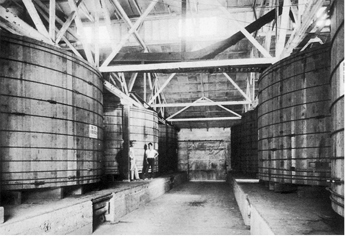

IN A WALNUT PACKING PLANT

California Fruit Growers’ Exchange

Studebaker-Pacific Corporation

BODY ASSEMBLY LINE, AUTOMOBILE FACTORY

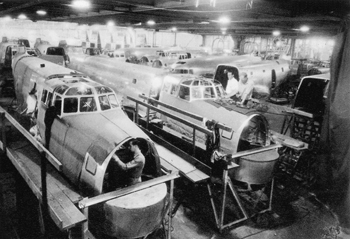

ASSEMBLY ROOM, AIRCRAFT FACTOR

Douglas Aircraft Company, Inc.