(if you want peace, prepare for war)

Robin Hood had his Merry Men, and I had Los Diablos, my Sangra homeboys. Robin Hood was a rebel, and so was I. Robin Hood stole from the rich and gave to the poor, and so did I . . . well, with one slight difference: I gave to myself. The way I saw it, I was the poor.

I was brought up in a religious environment and I needed some way of justifying my criminal behavior, so I hooked onto the idea that I was some kind of modern-day Robin Hood. I wasn’t going to steal from my own people, the folks who lived in the San Gabriel barrios, who really were poor, so I ventured north to San Marino, one of the richest cities in the greater East Los Angeles region. I was making so much money out of the burglaries, I managed to buy myself a car. I figured I was getting pretty good at this game. I’d created my own clica and my own little crime wave and, now that I was on a roll, I kept right on going.

One national magazine called the Sangra–Lomas conflict the most violent war between Los Angeles gangs at the time. The reality was that we were just two small Chicano neighborhoods battling it out with each other. Lomas has since spread out into the flatlands and extended its territory, and now the area has become gentrified, but back then Lomas was a former migrant community in the hills of South San Gabriel. There was a lot of poverty there, with no sidewalks, dirt roads, and lots of little shacks with chickens and goats.

In the 1930s, the Okies and Arkies—poor whites from Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Texas—escaping the Dust Bowl Depression settled in the hills. The Arkies were from Wilmar, Arkansas, and they even started a little gang, Wilmar, with a donkey as their symbol. By the 1940s, the majority of the people living in the South San Gabriel barrio were Mexican migrants, although a few white families stayed on. Some of them even learned Spanish and joined Las Lomas.

We called Lomas people “hillbillies,” but the truth of it was that, just like us, those communities were struggling with racism, police harassment, and discrimination on a daily basis. We didn’t see it like that, though. Some time back, a vato loco had crossed a line and fired that first shot, and now there was no turning back.

Pachucos tended to stay in their own area, but cholos had wheels, so now we could jump in a car, drive over to the Lomas barrio, and unleash some mayhem. To do that we needed guns and ammo. The right to bear arms really helped us out on that front. The folks in those San Marino homes wanted to protect their property and their person, which meant rich pickings for us. One night, we broke into a home and were rifling through cupboards and drawers when I heard one of the homeboys call out, “Hey guys, come over here. Take a look at this.” We raced into the next room and looked around. We were blown away. This was no average, run-of-the-mill home. We were robbing a gun collector.

The place was full of oak and walnut gun cabinets, four-gun wall racks with rifles in them, pistol racks, combo racks; he even had antique guns mounted in glass cases. We’d hit pay dirt, so we got to work. We slammed and smashed our way into those cabinets, filled our pockets with ammo, and loaded the guns and rifles into bags. The cache was so big that there weren’t enough of us to carry all the weapons into the car. One gun really caught my eye. It was sitting on its own in a glass case, and the moment I saw it I thought, That’s my gun. It was a Mauser P08 Luger semiautomatic pistol. Man, I loved this gun. It looked like a spy gun, something I imagined James Bond would use to take out the bad guys. The Germans must have liked that gun too—they used it in both world wars. They called them Parabellum-Pistole after a German firearm manufacturer came across the Latin phrase Si vis pacem, para bellum—“If you want peace, prepare for war.” That Mauser P08 became my gun of choice, and it wouldn’t be long before it would see some action.

With the death of Arthur and Puppet, Lomas had hit us hard. And after getting over the shock of our homies’ deaths, we only had one thought on our minds—revenge. So one night, we weaponed up. We were armed not only with pistols, like my Luger, but with rifles and sawed-off shotguns as well. We headed into Lomas territory, up in the hills, in two cars, looking for someone, anyone from Lomas, to hit. We were creeping around the neighborhood, headlights off, driving slowly, when suddenly we heard noises, voices in the dark, guys laughing. We drove closer and heard music, and could see flickering lights from a fire. There was a bunch of guys on a slope, cooking up some food and drinking wine. Then they clocked us, and now they were moving around, shadows in the dark. We weren’t sure who they were at first, until one of them ran down onto the street shouting, “Lomas!” Now we knew: these guys were a Lomas clica. So my homeboy wound down a window and shouted, “Get some of this, hillbilly!” Bam! A shot. Then I jumped out of the car, shouting, “Sangra Diablos! Que Rifa!” And we let rip. I saw one guy go down, and the others dove into a small ravine for cover. Then my homeboy turned to me and said, “That dude’s been hit, man. Let’s get the fuck out of here.” We sped off. I found out that the guy from Lomas had not only been hit, he’d lost an eye. Even though we were at war with Lomas, I felt bad about what happened to him. And still do, to this day.

Freddy at seventeen taken at an old-school photo booth, J.C. Penney.

I was fifteen years old when I first picked up a gun, and between sixteen and eighteen I was involved in a number of firefights. We were always on guard, knowing that we could get shot at any time, and always ready to go out and fire a gun.

Some shootings were random. You’d end up putting a bullet in someone just because he was Lomas, and because of the mayhem, you wouldn’t know who shot who. But one conflict I was involved in, when I was eighteen, really was personal. I was the target, so I had no choice—I had to hit back, hard.

It all started with a girl. She was really pretty, and kind of a loner, and she would hang around with Sangra one minute, and the Lomas vatos the next. She met a Lomas guy called Smokey. This was a problem, a big problem—because she was also going out with me. And, unbeknownst to me, Smokey found out what was going on before I did.

One day I was in the barrio, drunk, hanging out on the stairs of an apartment block. I was zonked out on the alcohol, nodding off, when suddenly: Bam! Bam! Bam! I woke up with a jolt. Smokey had pulled up in his car and, before I even knew what was going on, he’d fired six shots at me. There were bullet holes all around me but not so much as a single scratch on my body. He was a bad shot, I guess. I didn’t know who this guy was or why he was shooting at me. Then I came across this girl again—I was driving by and I spotted her in a phone booth. I got out of the car, walked over, and said, “Hey, who are you talking to?”

She seemed a little taken by surprise. “Oh, hey, I’m uhh . . . I’m talking to my friend . . . Bertha.”

“Oh, yeah? Who’s Bertha?”

She was really, really drunk, to the point of collapsing on the floor. The phone was now dangling off the hook, so I picked it up.

“Hey, Bertha. How you doing?”

Then I heard a voice. And it definitely wasn’t female.

“This ain’t Bertha, punk.”

“What? Who the fuck?”

“Lomas, motherfucker. I am going to kill you.”

“Oh, yeah? Fuck you. Sangra Varrio Rifa! Motherfucker.”

I hung up, but I still didn’t know who this guy was. Then I bumped into the girl’s brother, and he finally put me in the picture. It was this guy, Smokey. So now I’m figuring, This guy wants me dead, for real. He shot at me six times. And if he finds out I’m still alive, which he will, he’s going to finish me off. So I’m going to have to take him down before he takes me down.

I had to find out where this guy lived. I was lying on my bed, thinking, Who do I ask? I can’t ask the girl or her brother because they’ll know what I’m up to. Then I had a flash. I remembered this guy from Venice, his name was Tomás, who told me that he’d been in juvenile hall with Smokey. That was all I needed. I loaded my P08 Luger, jumped in a car with my homeboy Boxer, and headed into the Lomas barrio. Boxer was my best friend, my partner in crime.

I was full of rage, with one thought on my mind: I am going to kill this motherfucker. We parked the car. I covered up my Sangra tattoos and casually strolled around the neighborhood till I came across this young cholo hanging out outside his house.

“Hey, what’s up? My name’s Tomás, from Venice. I got busted and spent time with your homeboy Smokey in juvenile hall.”

“Oh, hey, man. How’s it going?”

“Yeah, I’m good. I was thinking, you know, since I’m in the neighborhood, it would be great to catch up with Smokey. I haven’t seen him for ages.”

“Oh, he’s around. I seen him last night.”

“You did? Oh, great. Any idea where he lives?”

“Yeah, sure. You go down the end of this street, take a left. Third house on the right. Kind of a yellow fence thing around the house. He lives at the back.”

“Oh, cool. Thanks, man.” And I walked off to Smokey’s house.

They say the Mauser P08 Luger was the definitive Nazi handgun. The magazine holds eight rounds so you take it out, load the bullets, and slot it back in. There’s a toggle on the back; when you pull it, the word Geladen appears on the barrel—German for “loaded”—then when you flip the safety on, it shows the word Gesichert—“secured.”

I spotted Smokey’s house, so I felt for my gun. The magazine was fully loaded. All I had to do now was flip the safety. I could hear it go click. My heart was beating like crazy, adrenaline rushing through my system. All my senses were on high alert. Boxer was close by in the car, waiting for me, ready to hit the gas once I was done.

I knocked on Smokey’s door. Nothing.

Then I heard a voice.

“Yeah. Who is it?”

“Hey, it’s party time, Smokey!”

“Who is this?”

“It’s me, man! Tomás, from Venice. I got the homies here, too. Let’s party, man.”

He opened the window.

“Who?”

I pulled out the Luger and fired: Bam!

Those things make a lot of noise. Anyone living close by would have definitely heard the sound. And, living in the barrio, they would have known it wasn’t just a car backfiring. I’d attracted attention, no doubt about that. But there was one thing I needed to know. Had I taken this guy down? After I’d fired, I’d heard a thud. Good. That was a yes. I ran back, toward the car. But then I heard him yell.

“You fucking puto!”

I turned ’round, thinking, Oh, shit. I thought I’d shot him good.

I’d aimed for his chest but I guess I hit his shoulder or arm or something. This was bad news. If I didn’t finish him off, he’d be back. So I turned ’round and headed back to the house, but Boxer shouted, “No, come on, man. They already heard the gunshots. Let’s go!” He grabbed me and dragged me back into the car. I didn’t feel I had the luxury to shoot someone and run away, but he knew the LA County sheriff’s deputies would be on the scene soon so he wanted to get the hell out of there.

Boxer screeched off at high speed and, still high on adrenaline, I was in full-on battle mode, buzzed out on the danger and excitement of it all. I wanted more. I wanted to inflict more harm—on Lomas. And that meant anyone from Lomas. I turned to Boxer and said, “I have another guy on my list.” His name was Mio, and I knew where he lived. We raced over to his house. I pulled out the magazine from the Luger. I still had a few rounds left. The car skidded to a halt. Again I unclipped the safety—the word Gesichert disappeared. Once the Luger is loaded and the safety is off you can just keep firing, bullet after bullet. And that’s what I did. I jumped out of the car and started shooting like crazy. I shot out all of Mio’s windows, dove back in the car, and Boxer sped off toward the freeway.

I’d bought the car from the proceeds of a burglary: I’d found twelve hundred dollars in cash and paid three hundred dollars for the vehicle. Driving around packing guns was risky business in case you were stopped and searched. So as soon as I’d bought the car, about six months earlier, I’d carved out a slit underneath my glove compartment and I’d stick the gun up that slit. Whenever the law pulled us over and they asked me to open up the glove compartment, I’d tell them it wasn’t possible, that the lock was busted. So far, it had worked.

We were driving through Alhambra when we saw flashing lights in the mirror. A cop was ordering us to pull over. He walked over and asked Boxer for his license. I didn’t even have a license to drive at all. At that point, we didn’t know who knew what. Did he know about the shooting? It didn’t seem like it. The guy was too relaxed. So Boxer was polite, giving him the “Sorry, officer” stuff, and I spun a story about why I had no license on me. Then he asked if we were aware of how fast we were going. Okay, just a speeding violation, so Boxer kept going with the “Sorry, officer. Was I really going that fast?” thing as the cop wrote out a ticket. But then, I started to hear the chatter on the radio: “Shots fired at . . . address . . . in the area of . . .” The Alhambra cop ignored it because we were so far from the scene. And then I got worried: he started calling it in: “Vehicle owner, Fernando Negrete . . . no license . . . speeding violation . . .” The San Gabriel PD picked up our names off the scanner, and then . . . everything changed. All of a sudden this cop, Billy Joe McIlvain, arrived on the scene.

McIlvain really hated me. He thought that I was the cause of all the gang problems in San Gabriel. Whenever I saw him I’d run, and whenever he spotted me, he would stop his car, right in the middle of the street, and run out, chase after me, and rough me up. His gun was already out when he came out of his car. He shouted, “Hold those two! Hold those two!” You could tell by the look on the Alhambra cop’s face that he was thinking, What the fuck?

“Those guys are gang members. They’re known to carry guns. I’m sure they are responsible for the shooting that just happened.”

All of a sudden the Alhambra cop’s gun was out.

“Get your hands away from the dashboard, up high where I can see them, and move slowly out of the vehicle.”

We got out of the car.

“Okay, face down, hands on the vehicle.”

Then Billy Joe McIlvain asked me, “What’s up with your glove compartment? You have a key?”

“It’s busted, officer. The lock broke ages ago.”

“Oh yeah?”

He bent down, poking around with his flashlight. At this point, I was really starting to sweat. I wasn’t sure about Smokey—I knew I’d hit him, but I didn’t know if he was seriously injured. And what if I’d killed someone at Mio’s house? What if I’d killed a child? I hadn’t intended to kill anyone at Mio’s, just wanted to terrorize him and his family. But Smokey, that was different. Him I wanted to kill, because he’d tried to kill me. But whichever way I looked at it, one thing was for sure: I was now in deep trouble.

Billy Joe McIlvain raised his hand in the air to signal the other cop. He was holding up my P08 Luger. He pulled back the toggle and took out the magazine. Next thing I knew, we were getting Mirandized: “You have the right to remain silent when questioned. Anything you say or do may be used against you in a court of law . . .”

I was taken to the LA County jail to await sentencing. In the mid-1970s, the county jail was totally different from the way they have it now; now, everything is locked down and the sheriffs have their observation control rooms and they see everything. But back then it was this crazy place: They had these long tiers with two floors, and just a rail separating them. They would open all the cells so inmates could roam around. I guess they had to do that to prevent a riot because the conditions in there were bad, very cramped. They had nine men sleeping in six-man cells. And they had four-man cells on the top tier, with six people sleeping in them. The sheriffs never went back there, so everyone was playing poker or blackjack. And, because you were allowed forty dollars every time you had a visit, people were playing for cash. They even had fires going, inmates brewing coffee. It was quite the place. We basically ran amok in there.

It was there in the LA County jail that I met two other artists who were a big influence on me. One guy was an African American with a serious background in art who’d worked on Hollywood movies. He drew full-body portraits of women on the walls that were incredibly realistic. I’d never seen anything like it. He used toilet paper to smear and shade the drawings. There was also another guy who drew on tablets with a ballpoint pen. His influence pushed my ability to draw faces, girls, and roses, subject matter like that, to a whole new level. From him I learned how to draw female figures, straight out of my mind, with no reference. That was a big turning point for me; it seemed like I became a different artist in there. I’d just needed a little more schooling by people like that, and I got it. In those few months when I was waiting to get sentenced, I was drawing beautiful female figures. I was getting better and better.

I was already in trouble with all the charges piled against me, but in the county jail I had another problem. Lomas was not only a bigger neighborhood on the outside, but on the inside as well. We had our police department, the San Gabriel PD, but Lomas was in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and the sheriffs were a lot tougher than our police. They’d break laws, plant evidence, stuff like that—anything to send Lomas gang members to jail.

One day when I had a visit, I saw six guys from Lomas in the visiting area. The visiting room had long rows with all these windows, so you could see who was in the next row, four or five rows down. I recognized some of the guys, and a couple of them were in the same jail row as me. They were looking at me and I had a bad feeling in my gut. Something was up. When I got back to my cell, a white kid came over and said to me, “Hey, dude. Are you in for shooting someone?”

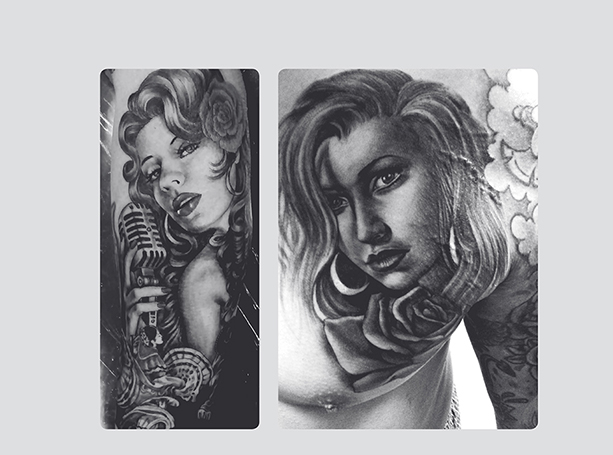

(Left) Latina singer and folklorico dancer. (Right) Chola tattoo.

“Who wants to know?”

“I heard these guys talking.”

“Lomas?”

“I think so, yeah. They were saying that you shot their homeboy, Smokey.”

“They’re planning on jumping me, right?”

He nodded. “We didn’t have this conversation, okay? They told me not to say anything.”

“I got it. Thanks.”

I found out that a bunch of Lomas guys from the outside were visiting their homeboys in jail and that’s how they knew: I was the Sangra guy, Coyote, who had shot Smokey. And this white kid had overheard everything.

They called the different sections “modules.” And if you were going to get hit it was going to be at night, after chow, because that’s when you could sneak into the other modules. That same night, I was in the chow hall and this one guy from Lomas stood up.

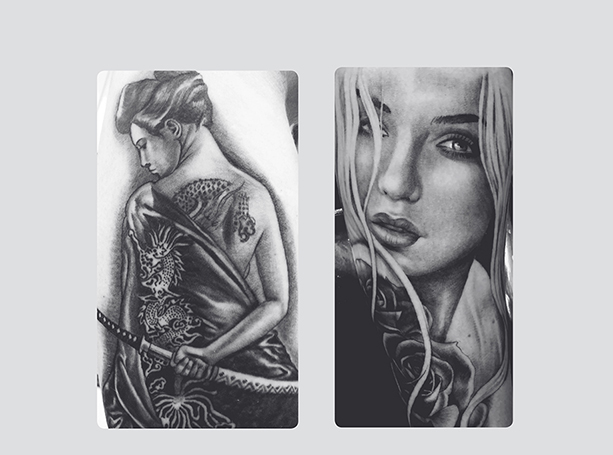

(Left) Kung Fu movie poster adaptation. (Right) Chola tattoo.

“Hey, you. You’re Coyote, right?”

“So what’s it to you?”

“We are going to fuck you up, Coyote.”

And he flicked his hand across his throat.

Then another guy chimed in.

“Yeah, and you know why, right?”

“Fuck you. Your homeboy got what was coming to him.”

“You’re a dead man, Coyote.”

“Fuck you.”

I knew I was going to get jumped, but my homeboy Andrés had prepared me for situations like this. Andrés was a good fighter, a strong guy. He had this technique when he got jumped: he put his head down, braced his legs, and then he just swung his arms upward, punching away. So when we jumped him in, all we could do was hit him on the top of his head and what’s more, he would land punches on us! He’d flipped it around, and kicked our asses instead. I didn’t know if I was going to able to do that but at least I had one possible way of defending myself.

There were already three Lomas guys in my module, and now four or five more had snuck back there, too. Before I knew it they were on me. I braced down and started swinging up. Andrés’s method worked. I got the main guy right in the mouth. They got me on top of the head and shoulders, but that was it. The other guys in the module saw what was going on and then there was a big commotion. At the very front of the module was a cop in a cage, and he could see everything that was going on. The sheriffs stormed in and the Lomas guys took off.

Later, one of the Lomas guys came over. He told me that he actually didn’t like his own homeboy. He said to me, “Hey, you gots heart, man. You’re alright.” I got a lot of respect from the guys in there for fighting with five guys and not getting knocked off my feet.

I went to court for sentencing. I was being tried for shooting up Mio’s house. I went in front of the judge, and she said to me, “Look at you. You look so young. You’re such a young boy. I just can’t send you to prison.”

She deliberated for some time. And then she made her decision.

“I’m going to reduce your charges.”

I was initially charged for shooting off a firearm at an inhabited location. That was a felony.

“I’m going to charge you with discharging a firearm within city limits.”

There is no way this would happen today. This was like being charged for shooting up in the air on New Year’s Eve or something.

“I’m sentencing you to one year in Youth Authority. You’ll go to Preston.”

I had barely turned eighteen, and I was one of those rare cases of an adult being sent to California Youth Authority. CYA was a state facility all over California. The two main facilities were Youth Training School, in Chino, Southern California, and Preston School of Industry, up in Ione, Northern California.

Still, no matter what kind of name they gave to those places, there was one thing I knew for sure: these weren’t juvenile halls, fire camps, or boys’ homes—these were prisons.