Rightly regarded as a bighearted city, Glasgow has several urban hearts. This chapter moves amongst them, traversing three inner-city miles and uncovering some of the often obscured historical and ideological foundations of the present-day municipality. Glasgow’s oldest heart, faithful and still beating, is the medieval Cathedral, about a mile east of the present-day town centre. Renaissance Glasgow had its heart farther south, in the area surrounding Glasgow Cross, between the Cathedral and the River Clyde; nearby lies Glasgow Green, open ground given to the city in the fifteenth century and a traditional heartland of political radicalism. From the late 1700s, however, a more modern municipal heart—George Square—began to develop. Once a “hollow filled with green-water, and a favourite resort for drowning puppies,” today the Square is Glasgow’s undoubted centrepiece. Long decked out with bronze memorials (which modernizers want relocated), it deserves to be the starting point for anyone sizing up the city.

George Square is a sustained volley of British Empire Victoriana. Though conceived in the Georgian 1780s, it was almost entirely redeveloped in the nineteenth century. Its monuments and monumentality confirm Glasgow as an ornate city of imperialism, and are themselves no strangers to strife. The first statue was erected before Queen Victoria’s accession to the throne—and was soon vandalized by local residents. In 1819, a fine statue designed by John Flaxman was erected (as the inscription around the base puts it) “to commemorate the military services of Lieutenant General Sir John Moore,” a heroic “Native of Glasgow” whom “his fellow citizens” wished to honour. Born in the city’s Trongate to a literary doctor and a professor’s daughter, Moore was schooled in Glasgow but made his name on imperial battlefields. Soldiering through America, Canada, the Caribbean, Ireland, Egypt, and across Europe from Corsica to Sweden—slashed to the skull, felled by fever, shot through the head—he seemed unkillable. Eventually, this battling Scotsman was cut down by French cannon shot at the Battle of Corunna (in northwestern Spain) in 1809, having said, reportedly, “I hope the people of England will be satisfied.” No one in today’s Glasgow could say that without sarcasm.

30. Dominated by the City Chambers building, George Square is the heart of present-day Glasgow. Its imposing public monuments pay tribute to Glaswegians who died in many a war. Yet its tallest column was erected to carry a statue of an Edinburgh man, Sir Walter Scott. Glaswegians are broad-minded, as well as big-hearted.

Yet, in his day, Moore exemplified Glaswegian service for a British Empire led by England but with Scotland contributing administrative nous and expendable fighting force. Soon to George Square was added a statue of a Glasgow carpenter’s son named Colin Campbell, whose first battlefield service was with Moore in Spain. Campbell eventually fought all across the Empire in territories ranging from Barbados to Hong Kong, growing rich in combat against Sikhs in India during the 1840s, then against Russians in the Crimean War, where his bright-uniformed Scottish Highland troops were nicknamed “the thin red line.” Later, Campbell led the suppression of the 1858 Indian Mutiny and so saved Britain’s dominion over that subcontinent. Victorian Glasgow, presenting him with a sword of honour, loved such sons, and Campbell, though he spent little time in his native city, took the name of its river when Queen Victoria, Empress of India, conferred a knighthood on him: he chose the title “Lord Clyde.” From one angle, Moore and Campbell can be seen as “men’s men,” even, in a city with a reputation for generous toughness, as examples of Glaswegian “hardman” machismo. Their world was at heart homosocial. Unmarried, leaving no known descendants, they might have felt at ease in a George Square where almost all of the statues depicted males; the sole woman was their celebrated monarch, haughtily confident on her pacing horse and holding what looked like a spear but was actually her regal sceptre. Her military commanders were, par excellence, fighters for empire, and many Glaswegians sailed abroad as their cannon fodder.

Though George Square, so much grander than its Edinburgh namesake, is, like many of the surrounding streets, quintessentially Victorian, Queen Victoria hardly saw it. She and Prince Albert (who pronounced Glasgow Cathedral “a magnificent building”) visited in 1849, when the Square appeared “like a neglected churchyard.” Not many months earlier, gun-toting rioters had scared the city’s establishment during Europe’s radical revolutions of 1848. The queen stayed away for almost forty years. Nothing, however, is more redolent of imperial Glasgow than the excitement which greeted her return in August 1888 to open the splendid new Municipal Buildings in George Square. By that date, the Square was described by a London newspaper as “one of the finest civic enclosures in the whole kingdom,” even if Glaswegian wags nicknamed it “our local Valhalla.” Its memorial statues ranged from one of Glaswegian chemist Thomas Graham, inventor of dialysis, to Robert Peel, pioneer of Victorian policing, sculpted in bronze by popular local artist John Mossman.

George Square remains solemnly impressive. Its statues have been rearranged over the decades, but it is still dominated by the 1888 Municipal Buildings, today termed the City Chambers. Designed by William Young from the nearby industrial town of Paisley, this grand Victorian fantasy of authoritarianism, headquarters of Glasgow City Council, was built while the city had some of Europe’s worst slums; yet it strives hard to evoke the regnant architecture of Rome and Venice. When Queen Victoria stopped by in 1888, it was still a building site. The Glasgow Herald explained that she would perform the opening ceremony “without . . . alighting from her carriage.” Glaswegians grew ecstatic about this rare royal visitor. To let her sense their city’s grandeur, the city’s artisans made a “Glasgow Gold Casket,” its front bearing “a view of the new Municipal Buildings from George Square, with [a] small sketch on each side representing Railway and Shipping Commerce.” Preparing to welcome Her Majesty, the city’s magistrates ordered themselves new robes made of black corded silk, lined with white satin, and trimmed with ermine. Decorated masts and banners were erected, in the hope they would make George Square and other parts of the city look unassailably Venetian.

Yet the queen, more used to Edinburgh than Glasgow, represented the remoteness, almost the untouchability of authority. Just as the high plinths in George Square raised its statues far above common passersby, so on Victoria’s visit to this most architecturally Victorian of cities, a ruthless apartheid separated hoi polloi from civic dignitaries. Nearly 1,200 policemen manned barricades designed to keep common folk far from their monarch. But as soon as her train arrived at the vast (now demolished) St. Enoch’s Station, people began to topple off the boxes and barrels they had piled up in an effort to glimpse her. Some boys who had climbed onto the roof of a public urinal fell through it when the glass panes shattered. Except for those granted spaces in specially erected stands round its perimeter, the crowds were cleared from central George Square by constables; “a little ragged urchin escaped” their “vigilance,” and onlookers cheered with typically Glaswegian gusto as he dodged among the officers. Addressing its largely prosperous middle-class audience, the Glasgow Herald noted this with wry amusement; but less than three decades later, when the boys who fell through the urinal roof and the jinking urchin were mature men, it was just such working-class people who would turn against Glasgow’s authority figures, whom they saw as oppressively controlling their lives and excluding them forever from the city’s structures of power.

After the queen’s brief visit in 1888, the new City Chambers was finished to a standard of sumptuous imperial opulence. Inside, where few of the poor from the slums ever went, visitors could ascend by “an elevator, fitted up by the American Elevator Company with a luxuriantly appointed car,” or could stroll up the magnificent pillared marble staircase past alabaster panels to the Banqueting Hall. The French monarch Louis XVI and the Doge of Venice are among those whose architecture is invoked in these interiors. Locals and tourists alike still marvel at the Faience Corridor and the now silk-wallpapered Lord Provost’s Room, to which Victoria in 1888 presented a splendid Lord Provost’s chair. Yet, however exotic, this municipal extravaganza has a confident Glasgow accent. Its Banqueting Hall is in part decorated with murals painted in 1899–1902 by some of those artists nicknamed the “Glasgow Boys.” John Lavery has depicted nineteenth-century industrial scenes, contrasting somewhat with the darker portrayal of a medieval Glasgow Fair by E. A. Walton. In time, on the exterior of the building’s frontage, a pediment was added to celebrate Queen Victoria’s jubilee. It shows the monarch receiving homage from her imperial subjects; a little way off are depicted the trades and industries of Glasgow.

If Victorian empire and heady opulence are part of the story of George Square, so is rebellion against such things. The splendour of the City Chambers also explains the counterbalancing tradition of socialist radicalism which sprang from the city’s poor. Just three decades after Glaswegians and the queen rejoiced in the opening of their civic palace, guns were mounted on it and trained on a rebel underclass no longer content to be treated as battlefront sacrifices. Machine guns on turrets threatened George Square rioters during the “Red Clydeside” era around the end of World War I. The suffragette movement and struggles over tenants’ rights had helped to radicalize Glaswegian women, such as Gorbals-born hunger striker Helen Crawfurd, imprisoned in Glasgow’s Duke Street Prison in 1913 after attacking police officers who were attempting to disrupt a suffragette meeting. Immediately after her release, Crawfurd smashed the windows of an army recruiting office. Later she bombed Glasgow’s Botanic Gardens. Militant women as well as men were involved in World War I rent strikes, as socialist parties in Glasgow and elsewhere made inroads into the ruling Liberal government at Westminster. Local schoolteacher John Maclean—another hunger striker, who was hostile to what he saw as an imperialist-capitalist war—was repeatedly arrested as he tried to campaign for an independent Scottish republic governed by “Celtic communism.” George Square may seem to be all po-faced Victoriana, but in the minds of many Glaswegians it is associated with a history far more disruptive and radical.

Appointed Consul for Soviet Affairs in Great Britain in the wake of the 1917 Russian Revolution, John Maclean opened a consulate at 12 Portland Street, Glasgow. Yet he soon fell out with the Soviet authorities because of his desire for Scottish independence. One winter’s day, in the volatile political climate of early 1919, around 60,000 men and women campaigning for a forty-hour working week were addressed by their leaders in George Square, while a few representatives of the protesters were allowed into the City Chambers. When the protesters’ spokesmen emerged, one of them was clubbed by a policeman. The George Square crowds were then baton-charged by police. The date, January 31, 1919, is known as “Bloody Friday.”

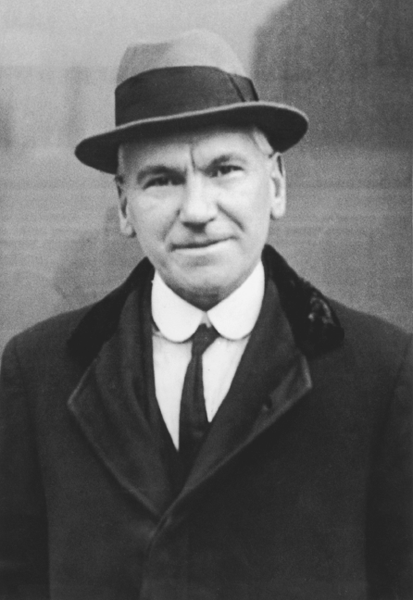

31. Glasgow schoolteacher John Maclean, appointed consul for Soviet Affairs in Great Britain after the 1917 Russian Revolution, became an icon of “Red Clydeside.” An antiwar campaigner, Maclean denounced World War I as “capitalism dripping with blood from head to foot,” and urged workers to undertake revolutionary activities. This photograph was taken after his release from prison in December 1918, when the authorities had attempted to certify him insane.

32. David Kirkwood is batoned by police after trying to calm angry demonstrators in George Square in 1919. An engineer, Kirkwood had been deported to Edinburgh from Glasgow because of his socialist agitation. Following the “Bloody Friday” riots of January 31, 1919, in George Square, he was charged with sedition. This press photograph helped to secure his acquittal.

Fearing Russian-style revolution and worried that Scottish soldiers might join it, the London government sent in 10,000 armed English troops and brought tanks onto Glasgow’s streets. No uprising happened, but history was turning against the sort of triumphalist imperialism that had given rise to the architecture of the City Chambers. Before long, several of those George Square protesters arrested in 1919 had been elected as members of the British Parliament at Westminster, where socialist parties were gaining power. By 1922, the Independent Labour Party had won ten out of fifteen of Glasgow’s parliamentary constituencies; a Communist named Walton New-bold was elected to represent the nearby industrial town of Motherwell.

This was the electoral high point of the so-called Red Clydeside movement. Broken after hunger strikes and terms of imprisonment, John Maclean died in 1923; more than 10,000 mourners attended his funeral. The following year, the more moderate Scottish Labour politician Ramsay MacDonald was able to form the first Labour government at Westminster, but the events of George Square in 1919—Glasgow’s last full-blown political riot—remain etched in Scotland’s political consciousness. Maclean is celebrated in poetry by Edwin Morgan for believing the poor should have access to life’s riches and for having let the authorities “know that Scotland was not Britain.” The Gaelic poet Sorley MacLean called his namesake simply “Iain mòr MacGill-Eain”: “great John Maclean.” Today most Glaswegians know something of the era of Red Clydeside and John Maclean, but not one of the radicals of that era is represented among the statues in George Square. Glasgow’s most iconic civic site, the Square remains a place of heartfelt ideological conflict, a monument to Victorian imperial values—yet it is also haunted by those values’ opponents. Men and women uncommemorated in bronze live on in the hearts of Glasgow’s people, who have continued to crowd the Square for protest rallies. A 1992 photograph shows about 40,000 men and women massed there at a peaceable political gathering. The single banner reads: “Free Scotland.”

The external grandeur and internal opulence of the City Chambers teeters on the edge of decadence. Rumours of administrative corruption have long been part and parcel of life in a city famed, like Chicago, for grid-plan streets and enterprising gangsters. Every so often, whispers give way to spectacular revelations and further rumours of scandal. Most recently, in 2010, the Socialist Leader of Glasgow City Council resigned suddenly, confessing to cocaine use. More sober and restrained than the City Chambers are George Square’s other monumental Victorian edifices. The imposing former General Post Office may look just a little like the Post Office in Dublin which was headquarters to the leaders of Ireland’s 1916 Easter Rising, but the Glasgow building has never witnessed a revolution. The one-time George Square branch of the Bank of Scotland, built in 1869 at the corner of St. Vincent Place, lost its sobriety when its long, polished dark-wood counter was transformed into the bar of a late twentieth-century theme pub; where once dark-suited, gentlemanly bank tellers checked ledgers under the ornate plasterwork and high, glass-domed ceiling, now thirsty punters sink their pints. Indoors and out, Glaswegians take Victorian grandeur for granted, and nowhere more so than when they walk through George Square. Among its statues are those of Liberal prime minister William Gladstone, as well as poet Robert Burns and engineer James Watt; but it says something about Glasgow’s broad-mindedness that on a high, fluted Doric column, pride of place has been given to the likeness of an Edinburgh man—Walter Scott. Erected in 1837, the western city’s monument to Scott predates the capital’s by several years—a fact seldom mentioned in Edinburgh.

Even as George Square was developing into modern Glasgow’s civic centerpiece, its Enlightenment citizens persisted in hanging out their washing to dry over its grass. Glaswegians have long treasured greenness. Gardeners are celebrated with biblical rhetoric inside the dome of the historic Trades Hall in Glassford Street, and a (sometimes ironic) local nickname for this city remains “the dear green place”—derived from the ancient Celtic glas cau, meaning “green hollow.” Once nestling in its own grassy landscape, the city’s original ecclesiastical focal point and still one of its most recognizable landmarks—the Cathedral—lies today about a mile east of George Square, at the other end of Cathedral Street.

Glasgow Cathedral is the finest building in Scotland which survives substantially intact from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Though thoroughly decentred by later building projects, it marks the earliest city centre, and is as essential as George Square to a proper understanding of Glasgow. Consecrated in 1197, the present building replaced an earlier church sacred to the memory of the sixth-century St. Kentigern, also fondly termed St. Mungo—from the Gaelic for “dear friend.” Glasgow’s patron saint, Mungo seems to have died around the year 612 beside the altar of his cathedral. Very little is known about him, but tradition has it that his mother was St. Thenew, known also as St. Enoch, her name now preserved incongruously in that of Glasgow’s large, postmodern St. Enoch Centre shopping mall.

Some late-medieval sources say Mungo came from Fife, and the emblems of Glasgow’s coat of arms (granted officially in 1866, but using much earlier motifs) relate to some of his miracles: finding an unfaithful queen’s wedding ring inside a salmon; resurrecting the tame robin of his mentor St. Serf; acquiring (perhaps from the pope) a handbell; and restarting a monastery’s fire by causing branches from a hazel tree to ignite through the power of prayer. Mungo’s emblems—fish, bird, bell, tree—are still recalled in a Glasgow rhyme about the city’s coat of arms:

Here’s the Tree that never grew,

Here’s the Bird that never flew;

Here’s the Bell that never rang,

Here’s the Fish that never swam.

The legends of Mungo are all about activity and a wonderful interaction with nature. This riddling rhyme is, oddly, about negativity. Tree, bird, bell, and fish remain frozen in heraldic stillness on the city’s coat of arms.

Awe, sometimes in short supply in Glasgow, is easy to feel when you stand in the dark crypt close to St. Mungo’s tomb. Here the most ancient heart of Glasgow is hidden now below ground level, in a magnificent grove of stone underneath the Cathedral’s floor. Close by is a twelfth-century wall bench and a vaulting shaft carved with plant-like decorations; the rest of the medieval crypt dates from the thirteenth century. Around the tomb rise four great carved columns, branching into arches that rhyme, in turn, with further arches beyond. The effect is like being in the midst of a hushed, lamplit forest, a prayer-space of grace but also of enormous solidity: one remains conscious, though not fearful, of the many tons of masonry supported by the elegantly branching, stylized organic forms. This is Glasgow’s sacred grove.

Upstairs, at the level of the cathedral’s main entrance, the thirteenth-century building manages to be at once plain in its massive, slightly asymmetric cruciform design, yet also soaringly elaborate. The cathedral is 285 feet long, its nave more than a hundred feet high, but—modified in the fifteenth century, then subjected to later attacks and restorations—the structure feels bigger. Separating choir from nave is a choir screen, or “pulpitum”—the only one of its kind left in a pre-Reformation nonmonastic church in Scotland. Though sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation iconoclasts got rid of altars attached to pillars in the nave and dedicated to such saints as St. Christopher, St. Kentigern, and St. Serf, nineteenth-century architects did more damage. They tore down two towers at the Cathedral’s western end, and awkwardly altered the western façade. Today, its exterior blackened by centuries of industrial pollution and its fifteenth-century spire retopped after an eighteenth-century lightning strike, Glasgow Cathedral is a resolute survivor. Usually approached from the west, past busy roads, it seems cut off by traffic from the present-day city centre. Nearby, the red-sandstone Barony Kirk asserts the city’s insistent Victorianism. Yet, set against the hillside beyond, which was once surmounted by the medieval bishop’s palace but is now given over to the remarkable Glasgow Necropolis, the Cathedral’s situation makes the most of the natural landscape. This building is the most obvious architectural statement of the city’s proud antiquity, as well as the great emblem of its spiritual life. Other grand edifices have come and gone nearby—Robert Adam’s huge, domed 1792 infirmary lasted little more than a century before Glaswegians demolished it—but the Cathedral sustains and is sustained by its city.

33. A 1935 view of Glasgow Cathedral, looking toward the Necropolis beyond. The present cathedral building was consecrated in 1197, replacing an earlier church sacred to the memory of Glasgow’s patron saint, St. Kentigern, also called St. Mungo.

Townhead, close to Glasgow Cathedral, has long been a poor area. Working in a studio above a corner shop, the artist Joan Eardley sketched and painted its gregarious children in the 1950s. Her pictures mix graffiti, tenement stone, washing hanging out to dry, and kids at play. One family of twelve, the Sampsons, became her regular models, and several of the Sampson children were photographed, their hair combed but awkwardly cut and their faces mischievously alert, in the midst of her studio’s clutter. Their mother disliked the Eardley pictures her children brought home as gifts; she tore them up and threw them on the fire. Much later, when she found out how collectible Eardley’s work had become, she realized, “We’d burned millions.” Today the blackened tenements Eardley painted are largely stone-cleaned or demolished, but the poor are not gone; down-and-outs are often seen round the back of the Cathedral or over in the grounds of the Necropolis. Burdened with legacies of ill-health and substandard housing, Glasgow has long struggled to look after its socially disadvantaged, as monuments in the Cathedral graveyard hint. One memorial beside the Cathedral’s east door commemorates George and Thomas Hutcheson, two seventeenth-century brothers who were successful Glasgow businessmen and left money to build a “hospital for entertainment of the poor, aged, decrepit men,” as well as a school for orphans. The brothers’ statues were sculpted in 1655 and still grace the handsome white façade of their rebuilt (1805) Hutchesons’ Hospital, which stands with its fine clock tower in Ingram Street, not far from George Square; their school for orphans, like so many of Edinburgh’s charitable schools, has metamorphosed into a fee-paying co-educational establishment in a city suburb, though its traditional school song still hints at a stern attitude towards the original pupils:

In 1640 the school began

With twelve boys on the roll.

They bent their will to the grim book drill

For the good of body and soul.

Singers of the song then chant “Hutchesons! Hutchesons!” in rowdy celebration.

The bodies, if not the souls, of many Victorian Glaswegians lie under the remarkable monuments of the Necropolis just east of the Cathedral. In the late 1700s, the area was called Fir Park; tellingly in the early nineteenth century, it became Merchants’ Park. At its summit, the well-off men of Glasgow’s Merchants’ House erected an almost 200-foot-high memorial to John Knox, which still surmounts the hill and proclaims that the famous Protestant Reformer’s legacy has led to “Honour, Prosperity, and Happiness.” In 1831, at the age of thirty-six, John Strang, a side-whiskered, well-traveled Glaswegian man of letters, published his Necropolis Glasguensis, with Osbervations [sic] on Ancient and Modern Tombs and Sepulture. This pamphlet argued that “a nation’s cemetery, and monumental decoration afford the most convincing token of a nation’s progress in civilization and the arts.” Contending that “a garden cemetery and monumental decoration, are not only beneficial to public morals . . . but are likewise calculated to extend virtuous and generous feelings,” Strang invoked the Catacombs of Rome, the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, and other necropolitan glories. He was not alone in wanting what he called an “eyesweet” landscape of tombs for Glasgow, and in 1832 a local Jewish jeweller, Joseph Levi, became the first person to be interred there.

From the start, the Necropolis was interdenominational and international. Its dead range from an exiled Polish freedom fighter, a German locomotive builder, and a Parisian professor of fencing (his memorial in the shape of a raised blade) to many of Victorian Glasgow’s doughty merchants and industrialists. Even though some monuments are in a dangerous condition, they form an astonishing array. An impressive Celtic cross memorializing a policeman is one of the earliest surviving works of Glasgow architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who once lived nearby, while the city’s most eclectically minded architect, Alexander “Greek” Thomson, designed the commanding 1867 monument to his Presbyterian supporter the Reverend Alexander Ogilvie Beattie, who died after commissioning from Thomson a great city church in St. Vincent Street. Much stranger than either of these memorials, the large Douglas Mausoleum—part Christian sepulchre, part Hindu temple—confirms the Necropolis as an architectural wonderland. Some original cemetery paths are grassed over, but the ground is well maintained. If a significant number of the dead are men from Glasgow’s imperialist past, such as East India Company officers, most made their money closer to home.

The most fascinating monuments are the least predictable: the twice-life-size bust of David Prince Miller memorializes an actor in Glasgow’s nineteenth-century “penny geggie” (cheap theatre) shows; a stumpy stone structure carved with a laurel wreath and lyre commemorates wood-turner William Miller (1810–1872), who dwelt close by in Dennistoun. Known throughout Britain and beyond as the “Laureate of the Nursery,” in his early thirties he wrote “Willie Winkie,” whose opening lines children can still recite. First published in 1841, the poem was soon anglicized, but was reprinted in its original Scots in Miller’s 1863 Scottish Nursery Songs and Other Poems, dedicated “To Scottish Mothers,” where it begins:

Wee Willie Winkie

Rins through the toun, runs

Up stairs and doun stairs

In his nicht-gown,

Tirling at the window, twirling

Crying at the lock,

“Are the weans in their bed, children

For it’s now ten o’clock?”

Some of the other poems in Miller’s book seem less suitable to nursery use. An example is the solemn English-language “The Poet’s Last Song,” whose speaker says, “Bring me my lyre” as “the cup of misery soon shall fill.”

The Necropolis has many reminders that childhood and childbirth in nineteenth-century Glasgow were often linked to death. Wealthy merchant and shipowner Allan Gilmour, author of Remarks and Observations by Allan Gilmour on a Tour of America in 1829, was widowed when his wife, Agnes, died at the age of thirty-three. Decades later, and still a single parent, he was buried alongside her near a sandstone obelisk on which a relief carving shows two very young boys in petticoats, heads bowed, clasping a sister, also young, on whose knee sits a skilfully rendered baby. The inscription reads simply, “Beloved Mother.” Mortality rates in nineteenth-century Glasgow were markedly high. Even living in a well-kept, newly constructed 1870s tenement in Fir Park, the young Charles Rennie Mackintosh lost four siblings in infancy. The Necropolis chronicles many such bereavements. One memorial, to “corlinda lee, queen of the gipsies,” states that she died at 42 New City Road, Glasgow, in 1900. “Her love for her children was great, and she was charitable to the poor. Wherever she pitched her tent she was loved and respected by all.” Mrs. Lee’s bronze relief portrait has been stolen from her monument, but the sandstone structure still records her young grandchild, “Baby May,” and the dates when she was “given” and “taken.”

Entry from the Cathedral precincts to the Necropolis is through a grand 1838 gateway whose striking black-and-gold iron gates were cast at a city-centre foundry in Queen Street. At the centre of each gate is the gilded sailing-ship emblem of Glasgow’s Merchants’ House—“the clipper on top of the world”—and the Merchants’ House Latin motto, Toties redeuntis eodem (“So often returning to the same place”). The way into the Necropolis was originally over the “Bridge of Sighs,” which lies beyond these gates and was built in 1833–1834 to span the Molendinar Burn. That ancient stream, associated with St. Mungo, became increasingly polluted; it was culverted over in 1877. If visitors can no longer glimpse this long-treasured Glaswegian watercourse, they can at least see a single medieval house, Provand’s Lordship, which was built in 1471 and still stands at 3 Castle Street, on the other side of the Cathedral precincts. Its masonry is largely of the late Middle Ages, as are its oak floor beams. The house was extended in 1671, its windows altered then or later. Inside, the floor plan is medieval: three equal-size rooms on each storey. Furnished with sixteenth- and seventeenth-century items, Provand’s Lordship, like the Cathedral, speaks of Glasgow’s venerability. Glaswegians have the additional satisfaction of knowing that no small house of comparable antiquity survives in Edinburgh.

34. Provand’s Lordship, now the oldest house in Glasgow, was built in 1471 and enlarged two hundred years later. Its floorplan is medieval. Today a small museum, it stands close to Glasgow Cathedral and within sight of some very different high-rise architecture.

35. Cast at a city-centre foundry in Queen Street, the grand, black-and-gold painted Victorian gates to the Necropolis feature the emblem of the Glasgow Merchants’ House—“the clipper on top of the world”—and that institution’s Latin motto, which means “So often returning to the same place.”

Until the nineteenth century, similarly ancient properties stood nearby, but the rest of the area has been extensively remodeled. Not far off, the modern St. Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art now stands on the site of the perimeter wall of the medieval Castle of the Bishops of Glasgow, and contains a mélange of exhibits relating to many faiths—from a New Caledonian ceremonial axe to a nineteenth-century Chinese dragon robe that was worn in Bernardo Bertolucci’s film The Last Emperor. From the top floor of the museum, visitors loath to venture among the tombs of the Necropolis can get a fine view of its monuments, looking past the gates to the Bridge of Sighs and the dominant hilltop statue of John Knox, with the Cathedral itself on the left. Inside the museum, on the same floor, artefacts from Glasgow’s many faiths, including Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity, are juxtaposed in a somewhat higgledy-piggledy fashion. Some exhibits allude to the city’s Protestant-Catholic tensions—not only through modern Protestant insignia, but also through a portrait of that most famous of all Scottish Catholic Renaissance monarchs, Mary Queen of Scots, who fled the battlefield when her forces were defeated for the last time in 1568, at Langside—now a Glasgow suburb proud of its verdant Queen’s Park.

So much building and rebuilding has gone on since Mary’s time that to perceive Renaissance Glasgow requires a purposeful act of imagination, as one stands amongst the city’s formidable Victorian and more recent buildings. Yet Renaissance Glasgow does persist, and is best represented by two steeples, each a survivor stubbornly present in the twenty-first-century city. Together, these make visible at least a hint of the “Glasgua” which seventeenth-century Scottish Latin poet Arthur Johnston saw as having its “Head held high among sister cities.” Praising churches which towered over house roofs, Johnston was writing of the area around Glasgow Cross. In the century that followed the Reformation, this became the heart of the town—close enough to the Cathedral and its associated college to retain links with ecclesiastical and academic life, yet sufficiently far from these structures to encourage new building and commercial expansion along the Clyde.

Erected in the first half of the fifteenth century, the original Tolbooth (the main municipal building of a traditional Scottish burgh) was removed in the seventeenth century and rebuilt as “a very fair and high-built house” with a new tower. It stood where its steeple still stands—at Glasgow Cross, a four-way intersection. Here the east-west streets of the Trongate and Gallowgate met, joined at right angles by the north-south axis of the High Street (running away from the river towards the Cathedral) and the Saltmarket, which heads southwards towards Glasgow Green and the Clyde. This basic street plan still exists, but the thin and square seven-storey Tolbooth Steeple of 1625–1627, erected around the time Arthur Johnston was praising Glasgow in Latin, is all that remains of one of the principal late-Renaissance buildings. Locked up and lonely among surrounding tenements and more recent structures, it is now a dignified traffic island, head held high above an intersection of busy inner-city roads.

To visualize these streets as they were at the end of the Renaissance and in the Enlightenment does require effort, but the nearby 1592 tower of the Tron Theatre (in former days the Tron Church) on the Trongate and the more distant 1665 Briggait steeple of the former Merchants’ House on the Bridgegate (now site of a splendidly restored Victorian fishmarket) may help. These were among the spires drawn by Dutch artist John Slezer in his 1670s view of Glasgow, showing a small city surrounded by woodland and hills. The Tron tower, built on the site of the 1484 pre-Reformation Catholic church of St. Mary and St. Anne, had its spire added in the 1630s. It is all that survives of the Renaissance kirk, destroyed by fire in the late eighteenth century. Solidly constructed, with its own built-in bootscraper for the merchants’ boots, the Merchants’ Steeple at the Briggait was part of a seventeenth-century institution which looked after the welfare of entrepreneurs’ families who had suffered bereavement or financial crisis.

Since the sixteenth century, Glasgow had been a base for incorporated crafts guilds which brought together workers such as tailors, weavers, and metalworkers (“hammermen”). There were 361 craftsmen in the city just after King James VI of Scotland succeeded Queen Elizabeth as monarch of England in 1603, and two years later the Trades House (which now occupies a handsome Adam building, the Trades Hall, in Glassford Street) was founded to regulate Glaswegian business. At that time, well over two hundred Glasgow merchants were exporting such commodities as cattle, fish, wool, dairy products, and hides. They imported corn and (not least from France) wines. The area around Glasgow Cross became these merchants’ hub—“a spacious quadrant, in the centre whereof their market-place is fixed,” noted the mid-seventeenth-century English visitor Richard Frank. He added that the Tolbooth was a “prodigy, infinitely excelling the model and usual build of town-halls.” It was also a place for the public exhibition of civic justice. When a Glasgow tradesman killed a rival’s dog in 1612, he was put in the stocks at the Cross, with the stinking carcase of the animal shoved right under his nose.

Glasgow’s principal “four streets handsomely built in form of a cross” impressed Thomas Tucker in 1656, when he surveyed the nearby inhabitants. Tucker concluded that, with the exception of students from the university (which then stood in the High Street), they were all “traders and dealers.” At that date, many of the properties around the Cross were thatched two-storey dwellings, some faced with stone, but many with wood. These burned easily. Inner-city thatched houses, even thatched tenements, persisted through the eighteenth century, but the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Glasgow Cross repeatedly impressed visitors. In 1662, John Ray admired a city “well built, cross-wise”; with its college buildings, it was “somewhat like unto Oxford, the streets very broad and pleasant.” Later seventeenth-century City Council legislation against the throwing of “excrement, dirt, or urine” from windows meant that the old civic centre escaped some of the more notorious dangers of Edinburgh street life. For Daniel Defoe in the 1720s, Glasgow was very much “a city of business,” exhibiting “the face of trade.” The mercantile-minded Defoe walked to Glasgow Cross and found it good:

Where the streets meet, the crossing makes a spacious market-place by the nature of the thing, because the streets are so large of themselves. As you come down the hill, from the north gate to the said cross, the Tolbooth, with the Stadhouse, or Guild-Hall, make the north east angle, or, in English, the right-hand corner of the street, the building very noble and very strong, ascending by large stone steps, with an iron balustrade. Here the town council sit, and the magistrates try causes, such as come within their cognizance, and do all their publick business.

Eager to defend the advantages of political union with Scotland’s southern neighbour, the Englishman Defoe stresses the commercial advantages offered by the right to trade with England’s former colonies. Some Glasgow merchants had extended their dealings as far as Barbados in the mid-seventeenth century, but it was in the eighteenth that increasing trade with places like Virginia and the Caribbean helped to bring in money that transformed the area—not least that part now designated the Merchant City. Wealth enriched merchants around Glasgow Cross, but the Cross was also a point of intersection between commerce and academia. Students and merchants mixed. More than that, the students were sometimes merchants’ children who themselves became traders, going on to benefit both their municipality and their alma mater.

One story among many illustrates this. After a failed Scottish scheme to establish a colony at Darien (Panama) in Central America, John Campbell from the West of Scotland settled in Jamaica, sending his son Colin to matriculate at Glasgow University in 1720. Five years later, Colin’s brother William matriculated too. Having returned to the Caribbean with a taste for science, Colin Campbell later set up an observatory there, then passed his scientific instruments to another Glasgow alumnus, Alexander Macfarlane, who owned a Jamaican sugar plantation and established his own observatory on the roof of his house in Kingston. Elected a Fellow of London’s Royal Society, Macfarlane was an “ingenious and learned mathematician.” Like the rest of the Scots in Jamaica, he was also thoroughly involved with the slave trade. He had an annual contract for the transportation of Ibo slaves, and in 1747 alone, around the time he was subscribing to the publication of Colin MacLaurin’s 1748 Account of Sir Isaac Newton’s Philosophical Discoveries, he bought 121 slaves. When this thriving, Glasgow-connected merchant and astronomer died in 1755, he bequeathed to Glasgow University his fine hoard of scientific instruments. Shipped to Scotland, this collection was slightly damaged in transit, so the university employed a young man who lived nearby to clean and repair the artefacts. Earlier, this youth had tried to establish himself as an engineer near Glasgow Cross, but had been prevented from doing so by the guild of hammermen, jealous of their own privileges.

The young man’s name was James Watt. In the nearby Clyde port of Greenock, his father had been involved in the construction of the first crane in that town, used to unload produce from the slave plantations of Virginia. In August 1757—after Watt had repaired the instruments from Jamaica, which included a fine Gregorian telescope—Glasgow University erected a new building, the Macfarlane Observatory, on a hill just a short walk from Glasgow Cross. Special medals were struck to celebrate the observatory’s founding, and Watt (whose statue later graced George Square) moved on from his restoration of scientific instruments to taking part in other aspects of the university’s endeavours. He assisted the chemistry professor Joseph Black, participating in discussions about how to improve steam engines to power vehicles and manufacturing processes. Out of such work emerged Watt’s design for a “separate condenser,” which allowed steam engines to run far more efficiently, and so encouraged the development of steam-powered industrial factories. Such establishments made Glasgow richer and more powerful, but the smoke from their chimneys close to Glasgow Cross would so pollute the air that within decades the Macfarlane Observatory would be rendered almost useless.

36. The Tolbooth Steeple, now islanded at Glasgow Cross, is a splendid survivor of Renaissance Glasgow. Near this tower, which was once part of a larger building, eighteenth-century “tobacco lords” paraded in their red gowns. Thanks to these traders and others, this part of Glasgow acquired the soubriquet “the Merchant City.”

This story, with its tangled interactions between academia, commerce, slavery, science, industrialization, and pollution, is emblematic of Glasgow as an intellectual, trading, and manufacturing crossroads in the eighteenth century. Except for the street layout, the Tolbooth Steeple, and a very few other vestiges, Glasgow Cross has changed out of all recognition. Imitating older originals and topped by a unicorn, the present-day Mercat Cross was designed by Edith Burnet Hughes in 1930; up the High Street, a twenty-first-century housing development called Collegelands confronts downmarket shops and tenements. The Macfarlane Observatory, the city-centre university, and most of the merchants’ premises are all long gone, though the Old College Bar (claiming that it was established in 1515) seems to have outlasted centuries of scholarly drinkers.

One of the telescopes from Jamaica which James Watt cleaned remains in the collection of Glasgow University’s Hunterian Museum, now on Gilmorehill in the city’s west end. The era when local merchants imbibed “Glasgow punch,” which mixed Jamaican rum with lemon juice, sugar, and lime, is memorialized—along with darker aspects of the city’s relationship with the Caribbean—in the name of Jamaica Street, which runs down to the Clyde. If you walk east along the Trongate, on the side of the street farthest from the river, towards Glasgow Cross, then about a hundred yards before the Tolbooth Steeple you come to the site where eighteenth-century merchants known as “tobacco lords” liked to congregate and promenade in red gowns, dominating the pavement next to a vast 1735 equestrian statue of King William III—“King Billy”—with his sword drawn. Presented to the city by a Glaswegian imperialist who became governor of Madras in India, this statue of the Protestant crusher of Catholics at the 1690 Irish Battle of the Boyne was moved long ago, and now stands, railed off, among trees just west of Cathedral Square. There was a certain irony in the fact that those red-gowned merchants, rich from the slave labour on sugar and tobacco plantations, were strutting their stuff near Glasgow Cross beside a statue whose long Latin inscription includes a phrase about Europe’s being saved from “SERVITUTIS IUGUM,” “the yoke of slavery.”

In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Glasgow, however, some thought the lot of slaves no worse than that of the local poor. This attitude was misguided, but working conditions in many of the city’s mills and factories were undeniably grim. A rapidly growing urban underclass was subjected to economic abuse and even, on occasion, to physical assault. Some violence was judicially sanctioned, a form of official retaliation designed to keep the poor in their place. One sunny Wednesday in August 1820, two years after the publication of Jane Austen’s Persuasion and the year Walter Scott published Ivanhoe, a Glaswegian called Thomas walked towards Glasgow Green to chop a man’s head off. Around the middle of the afternoon, he carried out the act he had been thinking about all day. It took him about a minute, and he used an axe. James Wilson, Thomas’s victim, who knew him by name, was a tinsmith in his early sixties who trained pointer dogs. He lived in the Lanarkshire village of Strathaven, a little south of Glasgow. Wilson was witty, and sometimes made up satirical verses. An occasional churchgoer, he had a taste for Tom Paine’s Age of Reason. Several of his friends were weavers, and for some years he had entertained democratic ideals. That was what got him killed.

James Wilson was one of a considerable number of people in the Glasgow area who were involved in the Radical uprising of 1820. The mad British monarch, King George III, had died shortly before, and in London there had been an attempt by radicals to assassinate government ministers. Very few people in the Glasgow area had the right to vote, and the powers-that-be wanted to keep things that way. Born above his father’s shop in Glasgow High Street, the most notorious Scottish democratic radical of the eighteenth century had been the middle-class lawyer and Latin poet Thomas Muir, tried in Edinburgh and then transported to Australia in 1794. Memories were long and fear of democracy was strong, so when a poster campaigning for “Equality of Rights” and dated “Glasgow, 1st April, 1820,” was distributed around the city, the authorities soon summoned the military. Issued on behalf of “those who intend to regenerate their country,” the poster urged its readers, if they supported equal rights, to “show to the world that We are not the Lawless, Sanguinary Rabble, which our Oppressors could persuade the higher circles we are—but a BRAVE AND GENEROUS PEOPLE, determined to be FREE[;] LIBERTY OR DEATH is our Motto, and We have sworn to return home in triumph—or return no more!”

In April 1820, fired up by this rhetoric, and often armed, in April 1820 “many hundreds drilled during the day time in the Green of Glasgow” and elsewhere around the city. Determined to arrest those who had been enthused by the ideals of the “most wicked, revolutionary and treasonable” poster, government troops fought radical weavers in the streets close to Glasgow Green. When things went wrong, James Wilson was among about twenty-five men from Strathaven who were marching into the city with a banner bearing the words “Scotland Free—Or a Desert!” Wilson was arrested, and later that summer sentenced to death. A mythology soon grew up around the radicals who were imprisoned and tried at several locations in Scotland in 1820, but we know some sustained themselves by singing Robert Burns’s famous song, “Scots, wha hae wi’ WALLACE bled,” inspired not just by the freedom fighter William Wallace but also by the democratic ideals of the American and French Revolutions:

Lay the proud usurpers low!

Tyrants fall in every foe!

LIBERTY’S in every blow!

Let us DO, OR DIE!

On August 30, 1820, his arms pinioned, and dressed in white clothing edged with black, James Wilson was taken to die at the edge of Glasgow Green. He walked towards his execution, the Tory newspaper the Glasgow Herald recorded, “with a pretty firm step.” Thomas, the headsman, dressed in a loose black cloak, his face concealed with a crepe mask, was carrying both knife and axe. When Wilson saw the multitude who had streamed over Glasgow Green to see him killed, he turned and said “carelessly” to his executioner, “Did you ever see sic a crowd, Tammas?” He then ascended the scaffold to be hooded. People in the crowd cried “Murder!” but a heavy presence of riflemen, dragoons, and other soldiers kept order with a show of force.

About five minutes after the body was suspended, convulsive motions agitated the whole frame, and some blood appeared through the cap, opposite the ears, but upon the whole he appeared to die very easily. At half past three, after hanging half an hour, his body was lowered upon three short spokes laid across the mouth of the coffin, his head laid on the block with his face downwards, and the cap taken off, when there was again a repetition of the disapprobation of the crowd. The person in the mask, who had retired into the Hall when Wilson ascended the scaffold, was now called; he advanced to the body, which was placed at the front of the scaffold, amidst the execrations of the people, and after calmly feeling the neck for a moment, he lifted the axe, and at one blow severed the head from the body, which he held up, and pronounced, “This is the head of a traitor.”

Though there is no monument to Wilson on Glasgow Green, the place has long been associated with popular radical struggles for democratic rights. Originally given to the people of the city as common grazing land by a fifteenth-century bishop, the grassy space itself, rather than any statuary, asserts freedom. For more than two centuries developers have sought to erect houses on, mine coal under, or drive roads through what is now a public park used by some of Glasgow’s poorest citizens. The developers have been fought off, usually with success; part of the park, the “drying green,” was used for centuries—until 1977—for hanging up household washing, latterly on lines suspended between “clothes poles.” Around the time of the 1832 Reform Bill, which extended (somewhat) the democratic franchise, 70,000 people gathered on Glasgow Green in support of the reforms. On April 13, 1872, the Green hosted a large open-air women’s suffrage meeting, where an audience of around a thousand was addressed by Scots-Italian campaigner Jessie Craigen. Most of her attentive listeners, according to the Women’s Suffrage Journal, were “working men of the most intelligent type.”

Associated with political activism, trade unionism, female emancipation, and the European temperance movement, and still a place of radical ideas as well as of down-and-outs, the Green was once, too, a site for popular theatre. Incongruously, it also displays military-imperial paraphernalia that range from Britain’s first monument to Admiral Nelson, victor at the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar, to one of the world’s most remarkable terracotta fountains, donated by a nineteenth-century manufacturer of pottery and toilets, Sir Henry Doulton, during the 1888 Glasgow International Exhibition. Restored in 2005 and looking thoroughly grand, this three-storey fountain is surmounted by yet another local image of Queen Victoria, who towers regally over figures representing her Scottish, English, and Welsh soldiery, her navy, and her subject peoples of Australia, South Africa, India, and Canada. So fine is the sculpted detailing that even the raised lettering on the buttons of uniformed imperial fighters can be made out. In case not everyone got the message, Sir Henry gave a speech about the fountain in 1890:

It symbolizes the Empire. I don’t think Englishmen, at least most Englishmen, rightly appreciate—I hope you do in Glasgow—the greatness and glory of our empire. The Queen rules over something like one-fifth of the inhabitants of the globe, and our material supremacy will stand or fall together. . . . May I dare to hope of the people of Glasgow that, inasmuch as this fountain has some lessons to teach, they will draw some of these lessons: that they will see how our empire was won by the enterprise of our discoverers and by the self-abnegation of our missionaries, and how it has been maintained by the valour of our soldiers.

Many nineteenth-century Glaswegians would have loved this oratory. Four years later, the terracotta statue of Queen Victoria was completely destroyed by a lightning strike; but despite the best efforts of modern West of Scotland vandals, it has now been restored to its triumphalist imperial grandeur.

The true monument to the spirit of Glasgow Green—to James Wilson, the supporters of women’s suffrage, and others—is hardly the Doulton Fountain. Instead, it is to be found inside the building which stands behind that fountain and is known as the People’s Palace. This large red-sandstone museum contains displays about Glaswegian popular culture and political life, not least the sometimes radical political activities associated with the working-class communities around the Green. High inside, under the central dome, are striking 1987 murals commissioned from artist Ken Currie by the Palace’s far-sighted former curator Dr. Elspeth King. These paintings commemorate the 200th anniversary of the day on which dragoons shot three protesting weavers who were part of a strike for better conditions in what was then the nearby village of Calton. Other paintings in Currie’s series commemorate the 1820 rising in which James Wilson was executed; the agitation of the Great Reform Bill period; Red Clydeside; the Hunger Marchers of the 1930s, and those Glaswegians and others who fought against fascism in the Spanish Civil War; the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders’ “work-in” of 1971–1972; and the Miners’ Strike of the 1980s. Wishing to show “the ebb and flow of an emergent mass movement, where the real heroines and heroes were the many unknown working-class Scots who fought so selflessly for their rights,” Currie, who painted these images when he was twenty-seven, has gone on to become one of Scotland’s best-known figurative artists. Idealistic and strikingly iconographic, his murals, like the artefacts in the museum below them, tell a story very different from that of the Doulton Fountain.

37. The elaborate, three-storey Doulton Fountain of 1888 is surmounted by Queen Victoria. Behind it on Glasgow Green is the domed, red-sandstone People’s Palace, a museum of Glaswegian popular history.

The People’s Palace offers a treasure trove of special everyday things—from the handsome green shopfront of a re-created dairy, its spherical lamp reading “BUTTERCUP” above the door, to radical handbills, portraits of old Glasgow characters, and the “big banana boots” designed by artist John Byrne to be worn by Glaswegian comedian Billy Connolly in the 1972 Great Northern Welly Boot Show, a satire based around the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders’ work-in. Free, like all the city’s museums, the Palace was originally proposed by Liberal Unionist councillor Robert Crawford and was championed around its inception by nineteenth-century Glasgow bailie William Bilsland, a baker who spoke out in favour of free libraries, museums, galleries, and parks. Long proud of its community spirit, Glasgow was one of the first cities in the world to offer a network of municipally coordinated public services: from swimming pools and hospitals to refuse collection, libraries, and museums.

Displaying a proud exposition about Glaswegian struggles for democratic freedom, the People’s Palace foregrounds telling local minutiæ. At its back, the spectacular “Winter Gardens,” a vast Victorian glasshouse larger than the museum itself, makes a convincingly tropical Scottish tearoom. When the museum first opened in 1898 as a cultural centre for residents of Glasgow’s east end, the original plan had been for it to receive visitors only once a week, for three hours on Sundays. Controversy over this generated additional publicity, and within the first six months more than half a million people flocked to see it. At that stage, exhibits about local history were confined to a single floor, and there were displays of history paintings as well as arts and crafts. The surprised and surely middle-class curator recorded how a crowd of riveters stood for half an hour discussing the “niceness” of lacemaking and embroidery, though he felt it necessary to post bills warning against “the spitting habit.” Right up to the 1970s in Glasgow (and even in Edinburgh), bus interiors had a painted notice: “no SPITTING.”

Respiratory diseases, relatively low life expectancy, poor high-school attainment, and urban deprivation were and are serious problems in Scotland’s great western city. In its Victorian way, the People’s Palace was a well-received attempt to improve the quality of life in the Glasgow Green area. The Green is famous, too, for its part in the Industrial Revolution. In the summer of 1765, while taking a breath of air and walking across the Green, local resident James Watt, who had been engrossed in discussing how to improve steam engine workings, came up with his notion of the separate condenser. Though Watt’s accounts of his 1765 invention tend to be dryly technical, an 1817 manuscript gives a most engaging version of the story, recording that his great idea struck him while he was “in the Green of Glasgow . . . about half way between the Herd’s House and Arn’s Well.” These pastoral landmarks are long gone, and the Green is much changed since Watt’s day, but later reminders of the Industrial Revolution are still to be found hereabouts. The most spectacular is the Templeton Business Centre, formerly the Templeton carpet factory, its elaborate crimson brick, red terracotta, and red sandstone frontage of 1888 designed to evoke the bright colours of the carpets then woven inside. The Templeton factory was built (like parts of the City Chambers) to invoke the Doge’s Palace in Venice, but conceals a former mill where weavers from the surrounding Calton once toiled. Behind the façade of this factory, whose origins go back to 1823, grand carpets were created for homes and halls in places ranging from Glasgow to New Zealand.

Today almost all the mills and large factories of this part of the city have disappeared, replaced by shops, offices, and modern social housing sited right beside remainders of former times. In Calton’s Abercromby Street Burial Ground, visitors can see an obelisk that marks the grave of the Glaswegian Reverend James Smith (1798–1871), a minister for forty years in America, where in Springfield, Illinois, he became pastor and friend to Abraham Lincoln. President Lincoln later appointed Smith as U.S. consul in Scotland. For all its pockets of social deprivation, the redeveloped Calton boasts a few handsome eighteenth-century buildings; nearby is the city’s second-oldest church, the beautiful St. Andrews-in-the-Square, which in 1745 sheltered Bonnie Prince Charlie’s army. In 1776 this kirk—today a concert hall marketed as “Glasgow’s Centre for Scottish Culture”—was the venue for the marriage of the abusive Glasgow lawyer James McLehose and his young bride, Agnes Craig, later famous for her passionate affair with Robert Burns. The poet sent Agnes (or “Clarinda,” as he called her) one of his most famous love songs, just before she sailed to Jamaica:

Ae fond kiss and then we sever;

Ae farewell and then forever!

Deep in heart-wrung tears I’ll pledge thee,

Warring sighs and groans I’ll wage thee.

When Burns wrote those passionate lines, the eighteenth-century Calton was already fast industrializing, its rainy daytime skies coming to look at times oddly and grimly benighted. Early twentieth-century photographs show the skyline beyond the Templeton factory filled with tall, discoloured chimneys, which kept the atmosphere densely polluted. The Calton is much cleaner now, and Glasgow Green greener. People can stroll beside the postindustrial River Clyde, pondering the rich, conflicted legacies of the radical weavers, Victoriana, the fondly kissed Agnes McLehose, and the commercially canny James Watt.