There is such a variety of dance and dramatic tradition throughout Indonesia that it is impossible to speak of a single, unified tradition. Each Indonesian ethnic and linguistic group possesses its own unique performing arts. Nevertheless, there are certain shared features among the groups, and most have several things in common.

Dance, storytelling and theatre are ubiquitous in Indonesia, elements of a cultural life that is all-encompassing and fulfils a wide variety of sacred and secular needs. Dancers, shamans, actors, puppeteers, storytellers, poets and musicians are members of the community, performing vital roles in informing, entertaining, counselling and instructing their fellows in the well-established ways of tradition.

The Barong dance dramatises the struggle between good and evil.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Ritual dances

Most tribes have ritual dances performed to mark rites of passage – births, funerals, weddings, puberty – and agricultural events, as well as to exorcise sickness or evil spirits, and, in the past, to prepare for battle or celebrate victory. The primary purpose of these dances is to appease the spirits. The Batak datuk (magician) of North Sumatra, for example, holds a magic staff as he treads with tiny steps over a design he has drawn on the ground. At the climax of this dance, he hops and skips, thrusting his staff into an egg on the ground. The Hornbill dance, performed by Kalimantan Dayak tribes for many generations, celebrated warriors returning from battle. Nowadays used as part of harvest festivals, the dancer, adorned with hornbill feathers, makes slow movements as though stalking and attacking the enemy.

Some dance schools teach boys to perform dance roles usually played by females. In the Javan town of Wonosobo, the lengger dance features men dressed as women, while the male Buginese bissu of South Sulawesi dances in a trance as a woman.

More refined ritual dances are performed by a select group, but in village dances, often all the males or females in the community join in. Female movements are generally slow and deliberate, with tiny steps and graceful hand movements; men lift their knees high and use their hands as ‘weapons’, often in imitation of traditional martial-arts movements (pencak silat). Accompaniment is provided by chanting, pounding of rice mortars (lesung), and bamboo chimes or flutes.

The kecak dance at Pura Luhur Uluwatu, Bali.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Group dances often involve the entrancement and possession of participants, best known of which is the Balinese Barong. The Barong-Rangda dance-drama is a contest between the opposing forces of good and evil in the universe, represented by a good lion-like beast called Barong and the evil witch Rangda. The battle ends in a temporary quelling rather than complete victory.

In the Balinese sanghyang trance dances, the performers are possessed by gods and animal spirits. In the sanghyang dedari, or heavenly maidens dance, two young girls dressed in white enter a circle of 40 to 50 chanting men, the kecak chorus. The girls dance in unison with eyes shut, then when they are finally possessed by goddesses they are clothed in glittering costumes and borne aloft on the shoulders of the men, touring the village to drive out evil.

In Central Java, one trance dance is variously known as kuda kepang, kuda lumping and jatilan, and consists of one or more riders on hobby horses made of plaited bamboo, accompanied by musicians, masked clowns and perhaps also a masked lion, tiger or crocodile similar to the Barong. The riders begin in an orderly fashion, trotting in circles, until one of them becomes entranced and behaves like a horse, charging back and forth wildly, neighing, and eating grass or straw. The others might follow his lead, and sometimes there is a confrontation between the masked animal and the horsemen. Eventually, the riders are brought out of the trance by their leader, and all ends well.

Legong dance performance, Ubud.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Another well-known trance dance from East Java is the reog, which tells the story of a prince who wants to marry a beautiful princess. He wears an enormous mask weighing 30–40kg (66–88lbs) adorned with a tiger or leopard head and peacock feathers, held in place by the performer’s teeth. The dancer – the singa barong – goes into trance while demonstrating his strength and prowess in his efforts to impress the lady. On some occasions, children or young ladies ride on top of the mask to impress the audience. In other versions of the reog, young boys or girls riding hobbyhorses, similar to the jatilan horses used in Central Java, accompany the singa barong.

Court dances of Java

Before the turn of the 20th century, all traditional rulers of the coastal and inland kingdoms maintained palace dance and theatrical troupes. But following the Dutch conquests, most court traditions lapsed into obscurity. Only in Central Java are courtly performances and royal patronage of dancers, actors and musicians still found and appreciated.

Java has by far the oldest known dance and theatre traditions in Indonesia, as depicted in stone carvings dating from the 8th and 9th centuries. The walls of Borobudur, Prambanan and others are adorned with numerous reliefs depicting dancers and musical entertainers, from market minstrels and roadside revellers to sensuous court concubines and prancing princesses.

Most of the traditional dances in Central Java are attributed to rulers of one of several Islamic dynasties, particularly those of the 16th to 18th centuries, with rulers having dances choreographed for special occasions. One renowned Javanese court dance is the bedoyo ketawang, performed in the Surakarta palace on the anniversary of the Susuhunan’s coronation. This is a sacred and private ritual dance said to have been instituted in the early 1600s celebrating a reunion between the descendant of the dynasty’s founder and the powerful goddess of the South Seas, Ratu Kidul.

Nine female palace dancers perform the stately bedoyo ketawang, attired in royal wedding dress, and it is so sacred that they may rehearse only once on a given day. Until recently, no outsiders were permitted to witness the performance, as it is believed that Ratu Kidul herself attends and afterwards ‘weds’ the king.

Another court dance from Solo, serimpi, was traditionally performed only by princesses or daughters of the ruling family. It portrays one or two duelling pairs of warriors, reflecting the balance of negative and positive cosmic forces. Following the rise of dance schools in the early 1900s, the serimpi became the standard dance taught to all young women.

Balinese dance

There are clear indications that dance and drama closely tied to religion have played a central role in Indonesian life since time immemorial. Other dances, however, are ceremonial, teach life lessons, or are simply for entertainment.

In Balinese dance, the Indian influence is evident in the facial expressions. Balinese costumes, with their glittering headdresses and elaborate jewellery, are of Hindu-Javanese origin and, as in Java, Balinese dancers adopt the same basic stance. Javanese court dances, however, are performed with slow, controlled, continuous movements, with eyes downcast and limbs close to the body. In contrast, the Balinese dancer is charged with energy, eyes wide and darting, feet lifted high, arms up, moving with quick, cat-like bursts that are startling.

Dances have evolved over long periods of time, and their original uses are now intertwined. In Bali, the legong keraton was originally a court dance developed for royal amusement, but it is now seen frequently at temple ceremonies. The baris warrior dance, often performed in groups and with weapons, appears to have developed out of a ritual battle dance. A solo baris performance is a true test of wits for the dancer and musicians, who must respond to each other’s signals to produce the quivering bursts of synchronised energy that are the essence of the dance.

Young Dayak women performing.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Folk dances

Outside the courts, there have always been dances performed by the common people. Thought to be too crude to be performed for royalty, these dances are relatively free of restrictions and change with the times.

Some folk dances, for example, are primarily for courtship. They are usually offshoots from fertility rites and women take the initiative, as in gandrung from Lombok. A female dancer selects male partners for short dance duets by tapping them on the shoulder with her fan. A similar dance, jogged bumbung, is performed in West Bali. In Kalimantan, young Dayak women perform graceful dances holding bunches of hornbill feathers as bachelors watch, hoping the ladies will approach them. In the past, in mainly Islamic Aceh (North Sumatra), women were prohibited from dancing, as it was considered erotic. Nowadays, the serampang dua belas is performed by mixed pairs, telling the 12 steps (dua belas) of introducing young people who are about to enter marriage.

From the 1950s, Indonesian performers began studying abroad, each bringing home new elements that they introduced into traditional dances or created new ones. The jaipong from Bandung, West Java, is considered by some to be vulgar, but its creator, Gumgum Gumbira, views it as humorous and spontaneous. Building on the past with sarong-clad female performers using some traditional body movements, the dance was intended to attract the attention of young people who were no longer interested in time-honoured dance.

Very popular, and now a Unesco cultural heritage treasure, is the saman dance from the Gayo highlands, near Aceh. Often called the ‘thousand hands’ dance abroad, between eight and 20 male or female performers kneel on the floor in a line. There is no music; instead, the exuberant cadence is created by clapping hands, pounding the floor and slapping the chest, with one person reading a barely audible narrative in order to maintain the cadence. Energetic and dynamic, the performance requires excellent coordination to keep the rhythm going.

A shadow puppet, Denpasar.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Theatre

Some theatrical traditions incorporate dance to such an extent that they are typically referred to as ‘dance-dramas’. In Java, all theatre seems to have its roots in the wayang (puppet) tradition, evident from the fact that all traditional Javanese theatre, whether performed by actors or by puppets, is referred to as wayang. Performed by actors on a stage, wayang topeng (mask drama) and wayang orang (dance drama) are the most traditional, with many of the tales, choreography and characters’ movements borrowed from the shadow play.

Puppet theatre

Thought to be derived from ancestral worship, puppet theatre is limited to a few locations in Indonesia.

The remarkable life-sized Batak sigale-gale puppet of North Sumatra is manipulated from below with cords and pulleys during funeral ceremonies. It is attributed to a local childless woman who, in somewhat macabre fashion, made an image of her dead husband and animated it to communicate with his soul. Some figures have water-filled sponges at the eyes to make them weep. Traditionally, at the end of the funeral, spears and arrows were shot at the figure to drive away evil spirits.

In Central Java, wayang kulit uses flat leather puppets that are perforated and fitted with movable arms for Ramayana and Mahabharata stories. In West Java, wayang golek (wooden rod puppets) perform tales from Indian epics and Islamic Amir Hamzah or Menak romances.

Balinese wayang refers to many types of shadow-puppet theatre with different repertoires. Wayang Ramayana stages stories from the epic of the same name, while wayang parwa performs episodes from the Mahabharata. An 11th-century Javanese exorcist legend of black magic is the focus for wayang Calonarang.

In Lombok, wayang Sasak works flat leather puppets to depict Islamic Menak romances, which were introduced from Java during the 17th century to spread the teachings of Islam.

Wayang topeng may have been inspired by ancient masked dances, but it was not introduced in the courts of Yogyakarta until the early 20th century, by the pedalangan (shadow puppetry) community. In Bali, mask plays are still popular, as they are in the courts of Central Java, and in some villages in the east and west of the island. Like puppet plays, masked performances are often used on television and in village performances to convey messages to the public, particularly satirical ones.

The highly stylised Javanese wayang orang or wayang wong (literally, human wayang) dance-dramas are said to have been created in the 18th century by one or another of Central Java’s rulers. Wayang orang became a part of the state ritual in these kingdoms, performed in an open pavilion to commemorate the founding of the dynasty and the coronation of the king, as well as at lavish royal weddings. The great age of wayang orang was during the 1920s and 1930s, when productions lasted days and would often employ 300 to 400 actors.

To keep up with the times, traditional dance and drama has in some cases blended with modern forms of entertainment to suit contemporary tastes. Javanese kethoprak (also spelled ketoprak) has connections to wayang wong because it uses classical costumes and gamelan music, but the dialogue is spoken rather than sung, the dancing is minimal and risqué humour is used to attract younger audiences. The topics are usually love stories, Javanese heroic romances or tales borrowed from Chinese folklore, and are frequently seen on television as well as at open-air venues. Evolving from this genre in order to relieve stress during times of political and economic change after Suharto’s fall, kethoprak humour today remains slapstick and full of lowbrow puns and cross-dressing.

Although traditional dance and drama face competition from modern entertainment, many educated Indonesians are dedicated to keeping these arts alive. There are government and privately sponsored arts high schools and academies in Java and Bali and two fully accredited universities, one in Jogja and the other in Denpasar. With state-of-the-art visual, performing and recorded media arts, these schools are turning out not only traditional, but also contemporary performers, choreographers, musicologists and ethnomusicologists, as well as photographers, film-makers and interior designers.

While it might seem that the students at these schools would be primarily interested in contemporary arts, many Indonesians – and some foreigners – attend specifically to delve more deeply into traditions. Someone yearning to become a dalang (puppeteer), for example, has to study Bali’s ancient Kawi language, Sanskrit or Java Kuno, and master vocal techniques to give personalities to each puppet character while simultaneously enrapturing the audience, sending the desired messages and ensuring their voices are strong enough to be heard. In addition, they need to learn hundreds of tales from the Ramayana and Mahabharata epics (for more information, click here), and many will learn to make their own puppets. Some students will study several genres until they find the right niche to pursue.

Excellent examples of performances mixing traditional and contemporary dance-drama can be seen on stage at Bali Safari & Marine Park in Gianyar and seasonally at Borobudur. Both use stunning costumes, animals and magnificent lighting effects.

In the performing arts realm, tourism helps by providing a commercial demand for the arts. A new generation of Indonesian choreographers, familiar with Western classical and modern dance, is now producing art-drama-dance (sendratari, literally translated as ballet), which is essentially a traditional dance-drama, minus the dialogue, that incorporates some modern movements and costumes. One of the most popular is the Ramayana ballet spectacular performed on a large stage in front of the elegant 9th-century Prambanan temple complex near Jogja.

Also emerging from these schools and academies are theatre groups such as Teater Koma (Theatre Comma), which has been active since 1977. Its shows were often banned during the Suharto era for lampooning the government – both the system and leaders – but they persevered and today attract audiences that reach across the population, from university students to professionals to diehard theatre fans. In a lavish Chinese opera production staged in 2011, a series of 7th-century Chinese tales were woven together, incorporating elaborate costumes and make-up, and also brought in Javanese puppets and traditional martial arts. The dialogue in the 4-hour-long production included the satirical jabs that Teater Koma is known for.

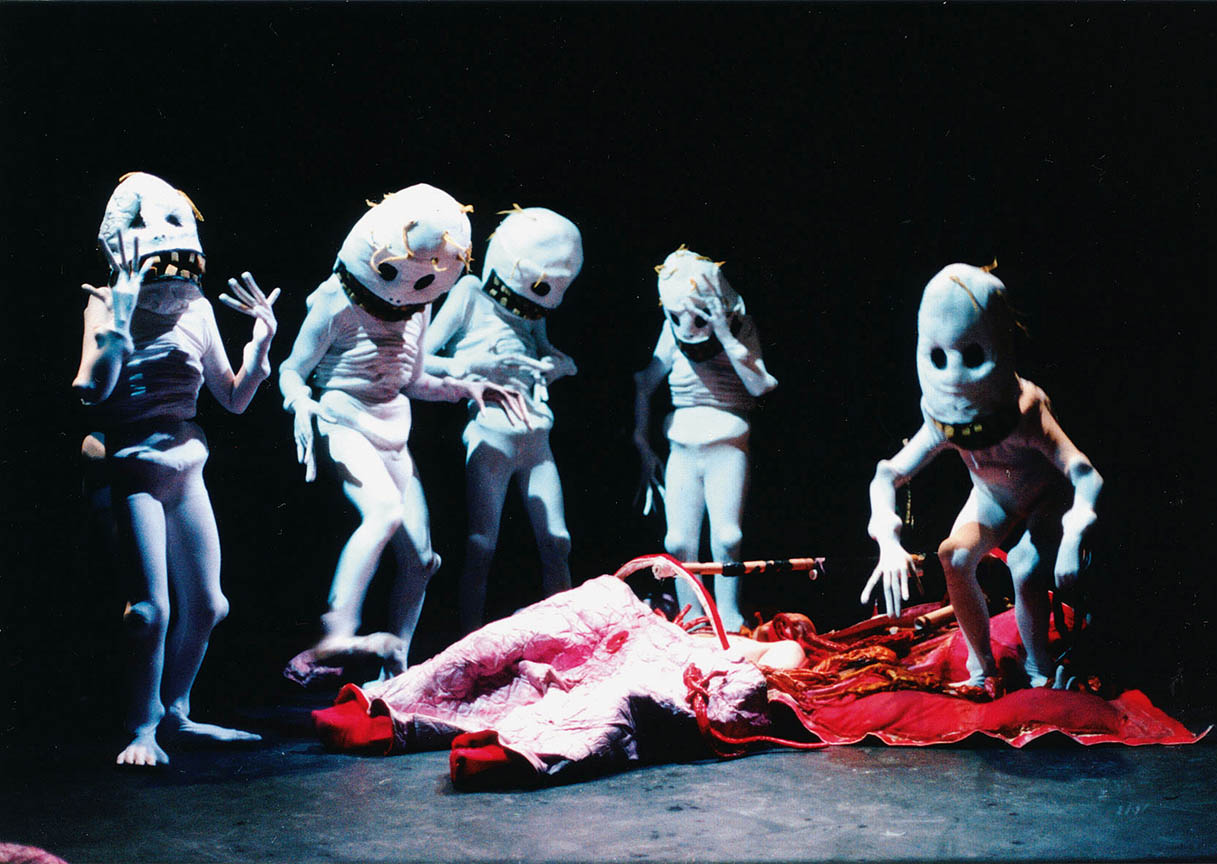

A Snuff Puppets Company production.

Daniell Flood/Snuff Puppets

The new generation of performers is also credited with finding overseas venues for local troupes and for inviting artists from abroad to combine talents with Indonesian actors, actresses and dancers, creating original contemporary work. One such collaboration between the Snuff Puppets Company of Melbourne, Australia, and Jogja artists has been ongoing for several years and has created a new genre using life-sized puppets, theatrical dances, popular music and cross-cultural dialogue about traditions and mythology in changing societies.

Indian morality epics

Central to Javanese and Balinese drama are the two great Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, stories of love and the triumph of good over evil.

The Ramayana and the Mahabharata epics are the basis of the most important wayang stories in Java and Bali. These gripping tales, one about an everlasting love and the other about a great war, are products of India that entered Java with the propagation of Hinduism.

Filled with high drama, they are morality plays, which over the ages have contributed largely to the establishment of traditional Indonesian values. Their fascination lies partly in the complex moral themes posed: life is never a case of absolutely black or white. Good heroes may have bad traits, and bad characters may have redeeming qualities. Although the forces of good do triumph over evil in the end, more often than not, the victory is incomplete; both sides suffer losses, and though a king may win a righteous war, he may lose all his sons as well.

The Ramayana

The Ramayana is filled with examples on how to lead a good life. Written by the poet Valmiki about 2,000 years ago, it tells the story of Prince Rama, who had been predetermined by the gods to be a hero, but would be put to the test many times. Rama is, in fact, an incarnation of the god Vishnu, and it is his destiny to kill the evil ogre king Ravana.

Owing to palace intrigues, Rama, his beautiful wife Sita (also spelled Shinta or Sinta) and his brother Laksamana are exiled to the forest. An ogre named Marica takes the form of a golden deer, luring Rama and Laksamana away. Ravana then carries off Sita to his island kingdom, Lanka. Rama’s search for Sita is helped by the monkey god Hanuman and the monkey king Sugriva. Eventually, a full-scale assault is launched on the evil king and Sita is rescued. Sita, in turn, proves her chastity during captivity in a trial by fire before Rama accepts her.

The Mahabharata

The Mahabharata, which was written after the Ramayana, is a collection of stories centring on a long-standing feud between two family clans, the Pandava and the Korava. The feud culminates in an epic battle during which the five Pandava brothers come face-to-face with their 100 cousins from the Korava clan. After 18 days of fighting, the Pandava emerge victorious and the eldest brother becomes king.

The great war portrayed in the Mahabharata is believed to have been fought in northern India in the 13th century BC. The war became a focus of legends, songs and poems, and at some point the vast collection accumulated over centuries was gathered into a narrative called The Epic of the Bharata Nation (India), or Mahabharata.

Important events that take place include the appearance of Krishna, an incarnation of Lord Vishnu, who becomes the adviser of the Pandava; the marriage of Prince Arjuna of the Pandava to the Princess Drupadi; the Korava’s attempt to kill the Pandava; and the division of the kingdom into two in an attempt to end the rivalry between the groups.

In one scene during the great war, Arjuna becomes despondent at the thought of fighting his own flesh and blood. Krishna, his charioteer and adviser, then explains to him that the soul is indestructible and that whoever dies shall be reborn, so there is no cause to be sad; it is the soldier’s duty to fight, as the outcome of the battle is predetermined.

Acting out the Mahabharata

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications