Papua, the western half of the large island of New Guinea, is Indonesia’s final frontier and one of the most extraordinary places on earth. Yet its sheer isolation (and therefore the expense of getting here), along with past news reports of social unrest, have kept all but the hardiest adventurers away: the few who have made the journey return home with rave reviews. It would be advisable, however, before departing for Papua to check the most recent news on the situation there. At the time of writing, the security situation has become challenging, as the separatist movement declared open war on the Indonesian military and non-Papuan civilians, insisting that their long struggle for independence was not over. Check government websites for current travel advice when making plans to visit.

The ‘Stone Age’ Dani, Lani and Yali tribes of the breathtakingly beautiful Baliem Valley render accounts of men wearing koteka (penis gourds) and bare-breasted women in grass skirts carrying piglets and babies in fibre bags hanging from their heads. The former head-hunting, cannibalistic Asmat have long been known throughout the artistic world for their primitive woodcarvings. A very few nature purists venture to the southeast, to Wasur National Park, where aboriginal tribes, and wildlife such as wallabies and cassowaries, make it appear more like Australia than Indonesia.

Papua also has a reputation for superb diving at Raja Ampat. A secret from the world until recently, news of the region’s amazing diversity of fish and coral species has captured the attention of divers globally, who have placed it top of their must-see lists.

Danau Sentani settlement.

Douglas Peebles

A Lani man at a festival wearing traditional wig made of human hair.

iStock

Jayapura and around

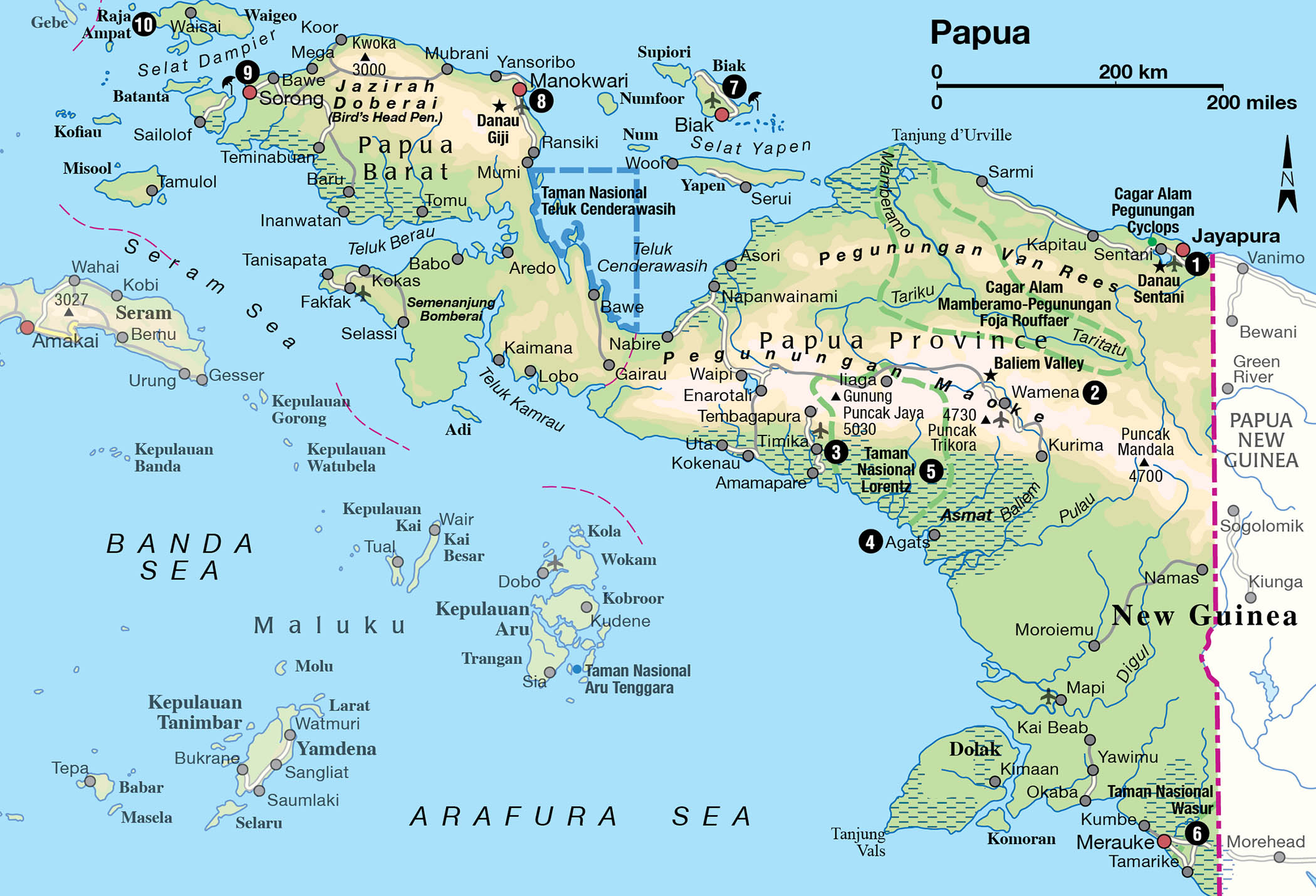

Jayapura 1 [map], the capital of Papua province, lies on Yos Sudarso Bay. Its constricted site along several indented, steep-walled coves is gorgeous. Highly recommended is the splendid view of the city from the base of a communications tower, on a steep hill just at the back of the harbour.

Jayapura and Sentani were unknown to the outside world until General MacArthur and the Allies arrived in 1944, turning the area into a giant military base. Hamadi, about 4km (3 miles) south of Jayapura, is the spot where the Americans landed in their quest to drive the Japanese out of New Guinea. Jayapura saw the biggest amphibious operation of World War II in the southwestern Pacific, involving 80,000 Allied troops. Rusting tanks and aeroplanes still rest half-buried in the sand. Tanjung Ria beach, known as Base G during the war, lies to the west.

While waiting for travel documents to be processed, many elect to go to Abepura, between Jayapura and Sentani, to visit the excellent Museum Loka Budaya (Mon–Fri 7.30am–4pm), on the Cendrawashih University grounds. It has a good collection of ethnographic pieces, as well as an impressive collection of Asmat art donated by the Rockefeller Foundation. On the same road, the Museum Negeri houses an interesting collection of both natural history exhibits and ethnographic pieces. Nearby, a crocodile farm displays several thousand crocodiles in varying stages of development waiting to become purses and shoes – give it a miss.

Fact

Danau Sentani is the third-largest lake in Papua and has a very good restaurant for a lunch stop. Boats can be hired here to Apayo island, where the residents still produce Sentani bark paintings. A visit can also be made to the island village of Doyo Lama, famous for its large woodcarvings and unexplained rock paintings.

At Gunung Ifar, 6km (4 miles) outside of Sentani, the remains of General MacArthur’s World War II headquarters can be seen. As the hill is on a military base, visitors have to report to the local military office to deposit their passports.

Tip

Those wishing to visit Papua’s interior must have their surat jalan (travel permit) processed at the police headquarters in either Jayapura, Biak or Sorong (for more information, click here). If you arrive at the airport at Sentani, a 45-minute drive from Jayapura, you will need to hire a car to get into the city and allow a day for your surat jalan to be processed.

Dani warriors.

Indonesian Tourist Board

Astonishing discoveries

The Mamberamo-Foja Mountain Nature Reserve, west of Jayapura, comprises 8 million hectares (nearly 20 million acres), much of which is untouched forest. With little human impact, scientists are discovering numerous previously unknown species each time they conduct research there. Exploration began in the late 1890s when women’s hats adorned with feathers from a bird that ornithologists had never seen before arrived in Europe. Subsequent British expeditions to find the origins of the bird failed. Fast-forward one century, when a team led by anthropologist Jared Diamond discovered the golden-fronted bowerbird in the Foja Mountains in 1979.

The region is so remote and bureaucracy so intense (together with local opposition to admitting strangers), that saying that arranging further expeditions has been ‘difficult’ is an understatement. However, following years of negotiations, a team from the Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Cenderawasih University, the Smithsonian Institution, Conservation International and others was finally allowed to enter in 2005. Results of subsequent explorations are now beginning to be published, the delay caused by the arduous task of determining what species the new discoveries belong to.

Tribesman in the Wamena region sporting a penis sheath.

iStock

Inland to Baliem Valley

The fertile Baliem Valley lies in Papua’s highlands, a 45-minute flight southwest from Jayapura. At 1,500 metres (4,900ft), the valley is cool, especially at night, but the midday sun can still burn. The area is surrounded by the steep Sudirman Mountain Range that kept it hidden from Western eyes until 1938 when American explorer Richard Archbold flew his seaplane over the mountains and sighted a lush valley dotted with the thatched roofs of Dani huts. The National Geographic reported the discovery in its March issue of 1941, but it was not until 1945, when the first missionaries made contact with the estimated 95,000 tribespeople, that the world was made fully aware of the valley and its inhabitants. The creamy-brown Sungai Baliem snakes through a valley that is 55km (34 miles) long and 15km (9 miles) wide, before pouring out through a southern gorge to the Arafura Sea.

In the interior, many waterways are traversed by precarious-looking bridges.

iStock

Dani tribal chief.

iStock

The Dutch established Wamena 2 [map], the only urban centre in the Baliem Valley, in 1958. It has a bustling, colourful traditional market – Pasar G.B. Wenas – where all the local tribes gather to sell forest and farm products and handicrafts: stone axes, baskets, fibre bags, bows and arrows.

The indigenous people of the Baliem Valley – Dani, Lani and Yali – are a Neolithic race with unknown origins. Until the 1960s, when steel was introduced to them, they were using wood, flint and stone for weapons and tools. Although foreign influence continues to chip away at their beliefs and traditions, in villages people live as they have done for centuries, following tribal laws and time-honoured customs. Older men still wear koteka (penis gourds), while some women wear grass skirts and carry babies, piglets or sweet potatoes in their fibre bags, known as noken, while younger folk often don Western wear. Disputes, which occur over land, pigs or women, are settled by fines and payment in pigs.

In the early 1990s, the government opened Balai Latihan Kerja, a cooperative to teach the Dani and Lani skills in pottery making, rattan weaving and leather working. This facility is located near the police station and visitors are welcome. There is no admission charge.

Fact

To express grief over the loss of a loved one, a young Dani woman uses a small stone to chop off her finger at the first joint. This tradition has persisted despite constant discouragement by missionaries and the government.

To visit the small Museum Wamena (free, but a donation is welcome), you have to ask for it to be opened for you. It showcases the daily life, traditions and ceremonial items of the Dani, Lani and Yali tribes. Behind the building is a suspension bridge over the Sungai Baliem, leading to a small Dani compound which welcomes visitors. You will be expected to pay to take photographs; 5,000 rupiah per shot should suffice.

Trekking in the Baliem Valley

In addition to unique ethnic groups, the main reason to visit Wamena is for the trekking – suitable for varying levels of capability – through breathtaking landscapes not seen elsewhere in Indonesia. In the highlands south of town, one- or two-day jaunts take hikers into the Baliem Gorge through sweet-potato fields and over stone fences surrounding Dani villages. Walk along the powerful Baliem River and cross a suspension bridge to Sogogmo village, surrounded by terraced fields and groves of wild sugar cane, ending at Kurima.

Tip

On another outing, hike to the top of Gunang Sekan for outstanding views of the southern Baliem and the Siepkosi valleys, passing fields of flowers, including orchids, mosses and carnivorous plants. It’s an easy walk into the fertile Pugima Valley from Siepkosi, the only area where beautiful pottery is made using primitive methods.

Travellers with only a few days usually arrange for a Dani village to perform a mock war and pig feast. Amomoge village, a 45-minute drive northwest of Wamena, is the most popular choice. Elderly village warriors will gladly show their arrowhead scars, attesting to wartime bravery.

A 15-minute walk from here is Jiwika, famous for its blackened, mummified warrior. In the past, important Dani were preserved with the use of herbs and a process of smoking in a secret ritual known only to a select few. Although the secret is still handed down to one couple in every village each generation, it has not been used for over 250 years. There is also a mummy at Akima, a 10-minute drive from Jiwika.

Behind Jiwika in the northern part of the valley is the Kotilola Cave, with lush vegetation, and further on is the vibrant market at Uwosilomo. From here, drive through a mountain pass surrounded by forest, taking time to study the fauna in the highland woodlands. Heading back to Wamena, there is another mummy at Meagaima.

A drive along the western side of Baliem Valley through grassy savannahs and acacia forests reveals a landscape totally different from the fertile, terraced fields elsewhere. Follow the route through Elagaima and Kimbim (where there are local markets), and on to Gunung Magi in the Pyramid region for a view overlooking a western segment of the Baliem River. The white clapboard houses, with chimneys, were built here by American missionaries, perhaps lonely for home, in the early 1950s.

A five-day trek will take those in good shape to Yali country, where it is easy to negotiate a night’s stay in a traditional hut or a local schoolteacher’s house. Or, weather permitting, drive to Habema Lake (about 3 hours; 90km/60 miles), a lake within a swamp surrounded by orchid-producing high mountain forest. On a clear day, you can see Gunung Trikora (4,730 metres/15,520ft) from here.

Into Asmat territory

Timika 3 [map] is dominated by the Freeport-McMoRan mine, the richest copper and gold mine in the world. Officially opened in March 1973 by then-President Suharto, Freeport is Indonesia’s fourth-largest taxpayer, and the mine is continuously surrounded by controversy.

Timika is also the jumping-off point for travel to Agats 4 [map], the only town in Asmat (the land as well as the people share this name). The Asmat, once feared head-hunters and cannibals, now fishermen and carvers, live in the harsh environment of an alluvial swamp on the south coast of Papua, bordered on the north by towering central highlands, making travel and exploration in this area extremely difficult. In 1770, English explorer James Cook stopped in Asmat territory near the Casuarina coast in search of fresh water. As Cook and his men approached the jungle, Asmat warriors appeared. Cook, fearing danger, fired at the group and returned to his ship. In 1913, this place was named Cook’s Bay.

Fact

The Asmat believed that misfortunes were caused by offended ancestral spirits. When a family member died, the spirit could not be released from the world of the living until an enemy had been killed by a close relative. Carving objects and naming them after the deceased while waiting to kill an enemy appeased the spirit. When village carvers were commissioned for an appropriate piece – perhaps a canoe or a war shield – the carver meditated until he felt the time was right to begin. From then until the piece was finished, the deceased’s family paid the carver’s family’s living expenses.

The first Asmat carvings were taken to Holland in the early 20th century, thus beginning the art world’s interest in these ‘primitive’ carvers. Although primitive art experts recognised the carvings of the Asmat as unique, the objects had no value to the Indonesian government. The Dutch gave up control of Papua in 1962, and when Indonesian officials arrived in Asmat in 1963, they ordered the destruction of the statues and put an indefinite ban on carving and on feast ceremonies, which were part of the rituals surrounding head-hunting, cannibalism and warfare. The ban proved effective and did indeed bring head-hunting and cannibalism under control.

Five years later the ban was lifted when the Indonesian government, in consultation with the United Nations, decided to open up the Asmat area to outside visitors. Around that time, the mysterious death of Michael Rockefeller, son of American billionaire Nelson Rockefeller, who came to Agats to buy Asmat carvings for museums in the United States, brought the art to world attention.

As the Indonesian government went about systematically destroying the art of the Asmat, Catholic missionaries Bishop Alphonse Sowada and Father F. Trenkenschug bought as many pieces as their funds would allow. Their collection now resides in the Asmat Museum of Culture and Progress (Mon–Sat 9am–noon, afternoons by appointment), the finest collection of Asmat art in the world. It is rare to find an old, high-quality piece of Asmat art today. In the past, the tools used by the Asmat were suitable for use only on soft woods. Many of these carvings were intended for a specific ceremony and then discarded. The recent introduction of metal tools now allows the Asmat to use hard woods such as ironwood.

The best way to proceed upon arrival in Agats is to go to one of the two hotels in town and ask around for an Asmat guide who speaks English. There are two villages near Agats – Syuru Kecil (small) and Syuru Besar (large). Syuru Kecil can be reached by elevated boardwalk, Syuru Besar by longboat. Either of these villages can be ‘hired’ for several hours to don their traditional dress and perform dances and perhaps even a ceremony. A motorised longboat can provide transport to either upriver or downriver villages more removed from Agats. However, the villages within only a one-day longboat journey are very similar to those near Agats.

Karowai tree people

Papua’s Karowai people are often referred to as ‘tree people’ because their homes can be as high as 45 metres (150ft) above the ground. They live in the dense jungles of eastern Papua, a three-day journey by boat, charter plane and foot from Asmat on the south coast. They may also be reached from the highlands of the Baliem Valley. An extended family or two small families might share a treehouse consisting of one large room with no room dividers, but with separate male and female areas. (Intimate relations are never allowed inside.) Hunting dogs and baby pigs live alongside.

The Karowai women spend their days caring for the children, cooking and sometimes making a foray into the jungle to collect their staple food, sago, and sago worms, the larvae of the scarab beetle. The men make bows and arrows, discuss the next hunt and clear land for growing sago palms. They also organise ceremonies, such as the yearly sago worm ceremony.

The Karowai have seen people from the outside, primarily missionaries but also a few tourists; however, a related group, the Karowai Batu, rejects any contact with outsiders. They are one of the few peoples left in the world today who choose to remain totally isolated.

Extraordinary festival costumes are a feature of Papuan highland tribes.

iStock

On a longer trip, it is often possible to negotiate to spend a night in the jeu, or men’s house. The Asmat speak their own language, but there is usually at least one person in each village who speaks Bahasa Indonesia, so the guide can act as translator. An introduction to the chief is the first order of business. The Asmat are usually quite happy to assemble their members in the men’s house and answer questions. It is not considered impolite to ask if there are any former head-hunters who wish to be interviewed. Having visitors is an exciting time for the Asmat, and they enjoy talking about the past. Often they will conclude such a session with drum-playing and chanting.

A southern crowned pigeon at Wasur National Park.

Luc Viatour

Lorentz National Park

Between Timika and Agats is Lorentz National Park 5 [map], a Unesco World Heritage Site (permits to visit are required from the police headquarters in Jayapura, the Forestry Ministry in Jakarta or the Freeport mining company). At 2.5 million hectares (6.2 million acres), it is the largest protected area in Southeast Asia, with the rare feature of incorporating a tropical marine environment, lowland wetlands and a snow-capped mountain, Gunung Puncak Jaya (formerly called Gunung Cartenz Pyramid). At 5,030 metres (16,503ft), Puncak Jaya is the tallest peak between the Himalayas and the Andes, and one of only three equatorial glaciers on the planet.

Merauke, the easternmost town in Indonesia, is the entry point to southern Papua. It was founded in 1904 by the Dutch in answer to complaints from British citizens concerning Asmat head-hunting raids on their side of the border to the east. Today, it is virtually one long street – Jalan Raya Mandala. There is a bank and a police station, where permits to enter Wasur National Park, southeast of Merauke, may be processed.

Wasur National Park 6 [map] is a 400,000-hectare (990,000-acre) natural treasure trove. A Ramsar wetlands protected site, the park contains several diverse habitats: extensive open-water swamplands (Rawa Biru), vast tidal mudflats, dry savannah grasslands, luxuriant mangroves, lowland forest and eucalyptus woodlands. In the rainy season Rawu Birus overflows its banks and the only access is by canoe. In the dry season, a jeep is required. An English-speaking guide can be found in Merauke if you enquire at your accommodation. The wildlife is more Australian than Indonesian; look for wallabies, bandicoots, cuscus and echidnas. Fabulous birdlife includes cassowaries, lapwings, spoonbills, crowned pigeons and eclectus parrots. The Kanum, Marori, Marind and Yei people who inhabit the park’s 14 villages are hunter-gatherers, and they actively participate in discouraging poachers.

Tip

Firewalking, once forbidden, is now performed in the Adoki village, 11km (7 miles) west of Biak. Men accused of adultery can prove their innocence by walking over burning-hot coals.

North coast explorations

Boot-shaped Biak 7 [map] island, lying one degree off the equator on Papua’s north coast, is the site of an Indonesian naval base, but during World War II it was the location of some of the worst battles fought between the Allies and the Japanese over control of New Guinea. Divers can explore shipwrecks sunk from these battles. The Japanese Caves are also of interest. Near the entrance to the caves, on Jalan Sisingamangarja, the Museum Cenderawasih contains a collection of war relics – one half for the Allied memorabilia and the other for the Japanese.

Southwest of Biak lies Teluk Cenderawasih National Park, encompassing the waters around Mioswaar, Nusrowi, Roon, Rumberpon and Yoop islands. The reef ecosystem here is part of the Coral Triangle region and is rich in many coral varieties, more than 200 fish species, four types of sea turtles, dugongs, blue whales and dolphins.

Bird’s Head peninsula

The Bird’s Head peninsula (Jazirah Doberai), located on the western tip of Papua, is so called because, on the map, it resembles the head of a huge westward-flying bird. Manokwari 8 [map], the capital of West Papua province, and Sorong are the principal towns on the peninsula. Manokwari was the site of the first European settlement and the first permanent Christian mission. Today, it remains a strong missionary centre. Gereja Koawi, a monument to the first missionaries, is located just past the hospital and behind the church. A Japanese War Memorial is also sited in the town.

Manokwari is host to over 30 separate language groups. The three main ethnic groups in the area are the Wamesa in the south, the Arfak in the Arfak Mountains and the Doreri along the coast. While here, take a side trip to Danau Unggi in the Arfak Mountains either by air or hike the distance in four days. The panorama is truly spectacular. The area is home to the endemic Arfak butterfly, famous for its shimmering wings.

The Sougb people make their home in the Unggi region. Although Christian, The Sougb still believe in black magic. The men wear red, the women black, and they have retained their traditional huts and customs.

Sorong 9 [map], the other large town in this area, has good beaches and reefs and attracts dive charters. The town has two World War II memorials to the Japanese who died here. As the hub of Indonesia’s lucrative eastern oil and gas fields and a timber export centre, it has an airport serviced by international flights incoming from Biak. It is also the gateway to Raja Ampat, the mention of which sends divers into a swoon.

Fact

Cenderawasih or birds of paradise, although protected, are hunted to this day. Their magnificent feathers were much sought after by Western milliners in the 19th century.

Diving at Raja Ampat

Although there are more than 1,500 small atolls in the Raja Ampat ) [map] group, there are four main islands: Waigeo, Batanta, Salawati and Misool. Raja Ampat (‘Four Kings’) gained notoriety when scientific data seeped out that the area may very well be the epicentre of oceanic biodiversity. Its position in the Coral Triangle– comprising Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, the Solomon islands and New Guinea – is significant. According to research conducted by The Nature Conservancy, 1,320 fish species, 553 varieties of coral and 699 molluscs have already been recorded, and the discovery of new species – such as the walking shark – are common. Couple this with crystal-clear waters, rainforests and mangroves, and no amount of difficulty getting here seems to be too much trouble. Alfred Russel Wallace visited Raja Ampat in 1860 in search of birds of paradise, and this amazing area lies just east of the line named in his honour.

Infrastructure here is rather basic, but is already changing quickly, with two airports under construction. In the meantime, flights land at Sorong and from here the islands are accessible by boat. At Wasai, the capital of Raja Ampat regency, there are new roads and a small health clinic, and budget cottages near Wasai beach as well as a few homestays. Several cruises and live-aboards have jumped on the bandwagon, and there are a few resorts.

Fact

The development of Raja Ampat is under the close scrutiny of international and local conservation groups, not only to protect its fragile ecosystems from an overabundance of tourists, but also because Sorong, as the logistical centre for timber and oil exports, is burgeoning.

Diving, of course, is the main event; frequently encountered are manta rays, giant groupers and large schools of barracudas and jacks, as well as sharks, whales and dolphins. In the shallows are pygmy shrimp and octopus and nudibranchs. Most explorations are drift dives due to strong currents. But there are also other activities. Kayak4conservation is a community development project and offers homestay-to-homestay programmes for experienced kayakers and with a guide and support boats for the less adventurous. The homestays are owned by villagers, trained by Westerners. Snorkelling is included in the adventure. Birdwatching is as exciting as the undersea world. While the fabulous bird of paradise is at the top of most avian enthusiasts’ must-see lists, there are lowland forest, mountain and riverine species to search for, as well as waders.