Pop quiz: You get visited by a genie—that’s right, the smoky guy from inside the bottle. What are your three wishes?

To be the fastest runner alive? (Eat my dust, Usain Bolt!)

World peace? (Oh, how noble of you!)

Hey, here’s a thought: How about an enchanted bag that would spew out cash whenever you wanted it? It’s a nice thought…or is it?

Since genies don’t exist, most of us have got to earn our money the old-fashioned (and magic-free) way. By working. Yes, at a job.

But going to work is about more than just spending your time doing something you’d rather not be doing. Because here’s the thing: The jobs that people work at every day do matter. Police officers keep you safe and stop the bad guys. Librarians quickly help you find the books and information you need to write tomorrow’s report. (Shhh! I won’t tell anyone you’ve been procrastinating.) A science professor at a university makes amazing new discoveries through research.

That’s how many people say they would choose to keep working even if they inherited enough money to live comfortably. Clearly we work for a lot of emotional reasons—not just to pay for stuff.

Plus, they get paid. And where does that money go? To tips for restaurant waiters, fees for dog groomers, bills from electricity companies that employ other people, and taxes that pay for roads and parks.

So work and money are important for creating a society that we all want to be a part of.

What’s more, if we didn’t work and everyone quit, that functioning society would change drastically. The world’s economies—not to mention public services, stores, and more—would tank. No police? Hello, crime. No science researchers, no new discoveries. And no money to pay for anything.

Besides, there’s another good reason to keep going to work. According to economist and author Dan Ariely in the U.S., studies suggest that people actually want to work because they identify with their job, not the money itself. Their work becomes a big part of who they are and gives them a sense of purpose and enjoyment. It’s one of the reasons little kids, when asked, will tell you, “I want to be a firefighter when I grow up,” instead of, “I want to make $45,000 a year fighting fires when I grow up.” The job is more important than the money.

Even animals feel the need to roll up their furry little sleeves and get down to business, says Ariely. In one study conducted by an animal psychologist back in the 1960s, a bunch of lab rats showed that they preferred to earn their food instead of going for the freebie.

How? A scientist guy gave his hungry rodent friends easy access to food from a cup—but only after they learned how to feed themselves from a dispenser that shot out a food pellet every time they pressed a tiny bar. Out of 200 rats, only one lazy specimen decided to keep chomping away out of the free cup. The other 199 eventually went back to the dispenser to press the bar and “work” for their food. In fact, some of them rarely ever went back to the free, plentiful vittles.

Animals aside, each person’s individual job is worth something to society. Each job has value. But how much? Now that’s the big question.

Ever wonder why a bank president makes more—as in, waaay more—money than your teacher? Or why the person who sells you buttered popcorn at the movie theater makes a lot less than an accountant? How do we decide that some jobs are worth more than others?

Before we answer that question, take a moment to consider the yap stone. Yap-stone money was a currency used in the 1800s by people who lived on Yap Island, found in Micronesia. The stones were made out of aragonite, which the Yap-ites (for lack of a better name) carved into huge, doughnut-like shapes.

Problem was, you couldn’t actually find aragonite on Yap Island. Instead, a burly bunch would brave the high seas in a homemade boat to travel to another island, quarry the stones—some as large as 12 feet—and somehow get them back home. The work was exhausting and dangerous.

It was that extra effort and danger that gave yap stones their high value. (You can say similar things about other precious stuff, like gold, which people have to work long and hard to find.)

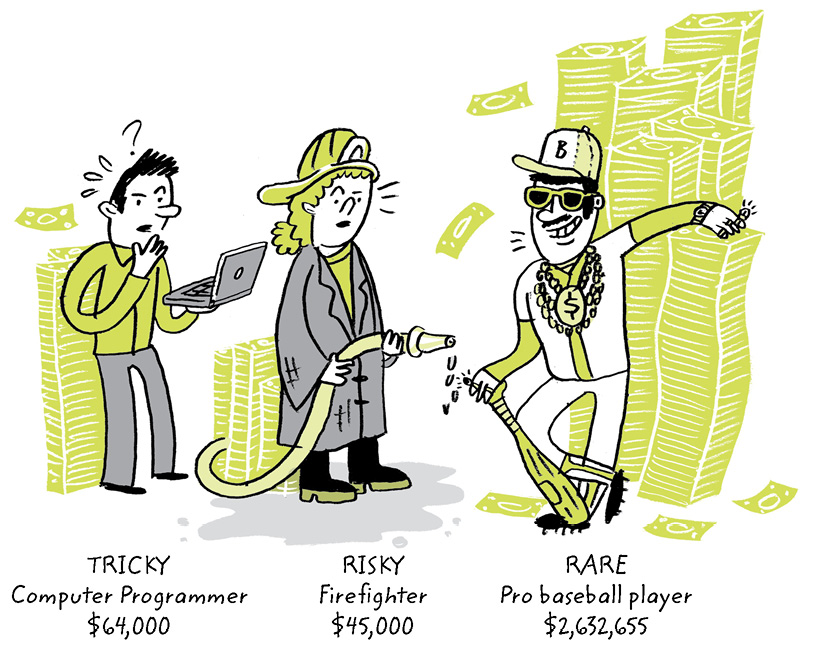

Here’s the deal. Just as we give things—like the yap stones—extra value because they’re hard to make or obtain, we also give people’s time value, especially if what that person does with it is dangerous, challenging, or rare. In other words, not many people have the skills or talents to do what that person does.

Right, so the more “special” your skills are, the better you get paid at your job. Sound fair? Well, it’s a little more complex than that.

So a major league sports player with rare talent makes over 58 times more than a firefighter? Does that makes sense? On one hand, when a firefighter runs into a burning building, she’s not only there to save lives, but is risking her own life as well. Some would argue this job is worth more to society than that of someone who plays ball for a living.

On the other hand, very few people can accurately pitch a ball that clocks in at 97 miles an hour (never mind doing that 100 times in a night). And don’t forget the massive amounts of money fans fork over to watch each game, not to mention the profits generated by ball caps, T-shirts, posters, and other merchandise. In part, ballplayers make mega moolah because they get a share of the team owner’s mega-mega moolah.

Whichever way you cut it, gauging work’s worth isn’t easy or even logical.

Some professions pay more for another reason: The person who does the job received a lot of training in order to do it right. That training probably took years to complete and cost a lot of money, too.

A hematologist (a doctor who treats blood cancers like leukemia), for instance, might spend more than 20 years in school and fork over hundreds of thousands of dollars to pay for it. Not too many people would become doctors if in the end the job didn’t offer enough money to pay off their education! Doctors, of course, also help people and save lives, so that adds to the value of what they do.

That’s a question a lot of people started asking in 2008, when the world faced the worst financial disaster since the Great Depression in 1929. Keep in mind here, we’re not talking about the friendly teller standing across the counter from you at your local bank. She had no hand in this. But many top bank employees were very responsible for the recession in 2008, by coming up with ways to give loans to people who normally wouldn’t receive them. These were people who didn’t have jobs, or had a track record of late payment. In short, their credit scores were too low. But some of the big financial bosses decided it would be a good idea to give them the loans and mortgages anyway. Why? They could charge a big fee called interest. The result? A ton of people couldn’t pay the loans back (surprise!) and got into a whole lot of financial hot water.

In 2009, how much money did the highest-paid banking boss make that year?

a) $8.2 million b) $18.7 million c) $900,000 d) $2 million

Answer: b) It was reported that John Stumpf, chairman of San Francisco—based Wells Fargo bank, earned a cool $18.7 million. Not bad pay if you can get it. Still, it was a far cry from the pre-credit-crunch days, when the top earner reportedly made $69 million!

Despite all that, some of the employees who made these decisions kept raking in millions of dollars in salaries and bonuses, while other people—maybe even your family or someone you know—lost their jobs and houses.

Even more ironically, some studies suggest that even in financially stable times, the hyper-inflated salaries the bankers receive do more harm than good. They actually make people less productive because that big, fat salary is so distracting. (Hey, how easy would it be for you to concentrate on your homework when you’d rather be thinking up cool ways to spend your $50,000 weekly allowance?)

That’s what a British think tank organization called the New Economics Foundation decided to find out. It’s an interesting question, except that, as you’ve just been reading, deciding a job’s worth can get pretty difficult.

Is one job better than another because it means a big paycheck? Is a job awesome because it involves something fun, like kicking a soccer ball around in front of screaming fans? Or is a job’s value best seen through the lens of the good it does for society?

Well, that’s how these economists wanted to analyze a job’s worth, so they set about answering the following question: “Does our salary reflect how much good our work does for other people and the environment?”

And here’s what they came up with:

(people who make the ads that convince us we need a nicer car or cooler clothes)

✘ Waste $17 of value for every dollar they earn because they persuade us to spend money we might not have. Soon, everyone is irritable.

(bean counters who help customers find ways to hold on to money at tax time)

✘ Waste $72 of value for every dollar they earn, if their job is to find ways for people to avoid paying tax. The researchers claimed that if we all just paid up, your town, city, or country would be in much better shape.

(people who move money around to make more money)

✘ Waste $11 of value for every dollar they earn because of the damage they cause to the global economy.

“Does our salary reflect how much good our work does for other people and the environment?”

(they’ll take your old plastics, glass, and paper and turn them into things we can use again)

✔ Create $18 of value for every dollar they earn by helping to turn old bottles into new bottles, tires into roads, and newsprint into toilet paper.

(they clean the rooms and keep germs from germinating)

✔ Create $15 of value for every dollar they earn and keep patients from picking up nasty bacteria and viruses that will cause them to get sicker.

(like your old daycare teachers and babysitters)

✔ Create $14 of value for every dollar they earn, since they offer a valuable service for families.

Without a doubt, these economists have come up with a new way to look at the issue. I mean, they sure made me think.

But like everything attached to economics, the buck doesn’t end here. Maybe high-end bankers deserve a higher salary than childcare workers because they spent years in school learning complicated math. Or because they lend money to people who otherwise wouldn’t be able to buy a home without saving up for 20 years first. That’s got to be worth something, right? Or maybe daycare workers are paid less because families would have a hard time paying their babysitter $38 an hour if they make only $19 an hour themselves.

Besides, not every accountant is out to rob the government, and not every banker is rubbing her hands whenever people go into debt. Life just isn’t that black and white. But here’s what we do know for sure: Every job definitely has an impact on other people and the planet. Sometimes good, sometimes bad, usually a bit of both. That’s why a job’s worth is so hard to pin down by asking if it’s good for society. There’s usually no clear-cut answer.

Sometimes, the history of a certain job tells society how much it’s worth—even if it doesn’t make much sense anymore. Take book authors and publishers. Back in the day, the only people who had the time to do something as frivolous as writing were those who were already wealthy. Publishing was considered a “gentleman’s profession.” In fact, it would have been quite unseemly to ask for a big advance on a book or demand a high salary as an editor.

Even though that reality is no longer the case for people who write, edit, and publish books and magazines (meaning that they are not just rich people looking for something to do), the industry still pays relatively little for all the work involved.

So here’s an idea. Let’s say we started paying better salaries for more “valuable” jobs. Would you rather be a banker or someone who comes up with nifty ways to make green energy? Would you look at banking and decide that work is not only uncool but also destructive?

Before you make that decision, maybe there a few other factors to consider. Remember, this is only one way to look at how to determine a job’s worth. You could also say that bankers do a lot of good, too. For instance, how many families would be able to afford a home without taking out a loan in the form of a mortgage? Not many at all. But banks, and the people who work for them, lend people money for many worthwhile reasons.

Meanwhile, students who might not otherwise go to college or university receive loans from banks to pay for their education. Then fast-forward 10 years. Eventually they find a good job, pay for their kids to go to school, and even give to charity.

Looking at the numbers on the previous pages, it would be easy to label banking careers as incredibly damaging to society, but the reality is far from crystal clear.

It’s a complicated business, this business of looking at what businesses we get into.

Bzzz! It’s that pesky alarm clock again, telling Future You it’s time to get dressed, grab your wallet or purse, and head out the door for work. But are you slipping into a fast-food restaurant uniform or reaching for a briefcase? Depending on your job, not only do your clothing and accessories change, but so does your paycheck. And make no mistake about it, the amount of money you pull in each week has a big impact on how you live the rest of your life. Pay matters.

Earning less will cost you, and not just in time you’d rather be spending on the beach or digging into a great book. It turns out the more broke you are, the more you’ll probably spend on essentials—things all of us buy every day.

20.7 hours to pay for a $150 iPod

5.8 hours to pay for a $42 pair of jeans

3.2 hours to pay $23 for a movie and snacks at the theater

53.8 hours to pay $390 for the end-of-year class trip to Washington, D.C.

14.6 hours to pay for a $150 iPod

4.1 hours to pay for a $42 pair of jeans

2.2 hours to pay $23 for a movie and snacks at the theater

38 hours to pay $390 for the end-of-year class trip to Washington, D.C.

7 hours to pay for a $150 iPod

1.9 hours to pay for a $42 pair of jeans

1.1 hours to pay $23 for a movie and snacks at the theater

18.1 hours to pay $390 for the end-of-year class trip to Washington, D.C.

Earning less money an hour is a big drag—on your personal time. That’s because minimum-wage earners have to work more hours to make the same amount as Mr. Moneybags.

At first, the difference between Devin’s and Josephina’s wages doesn’t seem like that big of a deal. What’s three bucks? But as soon as you start adding up the hours, it quickly becomes apparent that class-trip-bound Josephina is 15.8 hours richer than her buddy Devin. Plus, she was able to use that time to study, practice with the school choir, and hang out with her friends. And Calder? By landing a well-paying job, he’s the hands-down wealth winner.

“You got the job!” exclaims your new boss as he thwacks you on the back and shakes your hand. “In fact, take two jobs! Or how about three?”

Is this some kind of weird alternate universe where job hunters rule the world with their magic powers of persuasion? No, it’s the job market of 2021! That’s about the time that some economists predict the greatest number of baby boomers—that huge group of people born between 1946 and 1964—will retire. Just in time for you to swoop in and land the job they’re leaving behind.

You’re hanging out with your grandfather, just shooting the breeze, when he gets started on his favorite topic: money.

“I remember when I could buy a soda at a ball game for 5¢,” he tells you. “And if I wanted to ride the subway to the game, that cost a nickel, too.”

So what makes that soda at the stadium set us back $3.50 today? Part of the explanation can be boiled down to one word: inflation. Of course, prices go up for other reasons, too. For instance, the price of fresh lettuce can increase by a dollar or more if a hungry swarm of grasshoppers stop in for a bite. Lettuce is suddenly hard to come by, so the price goes up. But when it comes to steady and prolonged increases, inflation is usually the culprit.

Everybody needs to be concerned with inflation because it can affect how much buying power you have. Because even if you do make a good salary, inflation can make the money you earn worth a lot less eventually.

Darned inflation. If the price of a bowl of noodles, a haircut, or a skateboard will keep increasing anyway, what’s the point of working unless it brings in a load of cash? Hold on. There’s yet another way to give a job value—and that’s what the job is worth to you.

As the rat experiment at the beginning of this chapter showed us, working to earn money can be rewarding. And if you actually enjoy the work itself, all the better. Think about your favorite subject at school. Is it math? Writing? Science? Now consider how you feel when you’re dividing numbers, writing an awesome story, or conducting a cool experiment. That’s exactly how it feels when you’re doing a job you love. Work feels like play. Oh yeah, and your paycheck pays for stuff, too.

Many people will choose to work a job that pays less than others if it means that they are doing work they love.

That’s right. Not everybody thinks money and high-paying jobs are the answer. Just this afternoon a friend let me in on a secret about her grandfather and his stance on salary. In short, he didn’t care much about money. Or rather, he cared about it a lot more than the rest of us.

By 2020, 70 percent of all new jobs will expect you to have some kind of university degree, college diploma, or apprenticeship training.

Jane’s grandpa used to turn down raises and high salaries in exchange for lower ones. In one case, a company offered him $3,000 to do a job. He told the new boss he would take it, on one condition: they had to give him $2,000 instead. He decided his profession paid more than the work was actually worth. Besides, he had so much fun doing his job, it gave him more satisfaction than money could buy.

For the record, although my friend respected her grandfather’s decision, she still wished he could have just given her the money instead! Because who knows? Maybe she could have used that money to start her own snake-charming business...