You know the feeling. You’re walking through the mall or window-shopping downtown, minding your own business, and BAM! Out of the clear blue sky some wonderful whatchamacallit beckons. In no time flat, your nose is against the glass, your body feels all tingly—and you’re dreaming about how much better your life would be if you just had that thing.

It looks like you’ve just come down with a bad case of the “want it, need it, gotta have it” syndrome.

Hey, we all know what that feeling is like. Because let’s get one thing out in the open right now: Buying stuff is fun. Not only are stores set up to make shopping enjoyable (hello, flattering lighting and awesome music), but you get to go home with a new pair of snappy shoes or the latest video game and blast your way to extra levels.

What’s more, spending also keeps the economy pretty healthy. For example, even when you buy something as simple as a bag of popcorn…

And so it goes, on and on. In short, without spending, businesses of all kinds are in trouble and people lose jobs.

But there’s also a dark side to spending money—especially if you spend too much. Or spend unwisely. In most cases, the key to this is learning how to ignore (or at least bargain with) that “want it, need it, gotta have it” syndrome we all suffer from. Easier said than done? Let’s start by taking a look at one of our biggest spending issues. I call it lotsa-stuff-itis.

But economists call it over-consumption.

The door of your closet, that is. Because if you’re like most people in the Western world today, your cabinets and drawers are probably chockablock full of stuff you no longer wear or need. Seventeen sweaters? Check. Eleven pairs of shoes? Check. A stack of old toys and gadgets as high as your nose? Okay, you’ll cop to that, too. It’s not just that you’ve outgrown these items (although you may have). It’s that you’ve simply become bored with them, or frankly, never really needed them in the first place. It’s called over-consumption, and it’s on the rise.

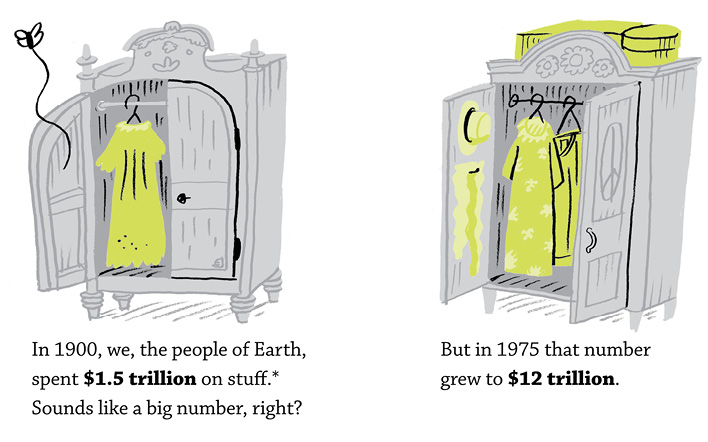

* So what exactly is “stuff”? In this case, it generally means everything that we buy—even the essential items, such as food or clothes. Just as people can buy lots of books or toys they don’t need, a family can also buy more groceries than they need to survive.

Good question. Consumption is all about buying things that we need in order to survive. Warm clothes in cold climates. Food for the week. Consumerism, however, focuses on things we want. Five winter coats, for instance, or a specific brand of cereal that we saw on a TV commercial that looked cool. When you hear people talk about North America’s “consumer culture,” they’re talking about our society’s love of buying things we want but don’t need to live.

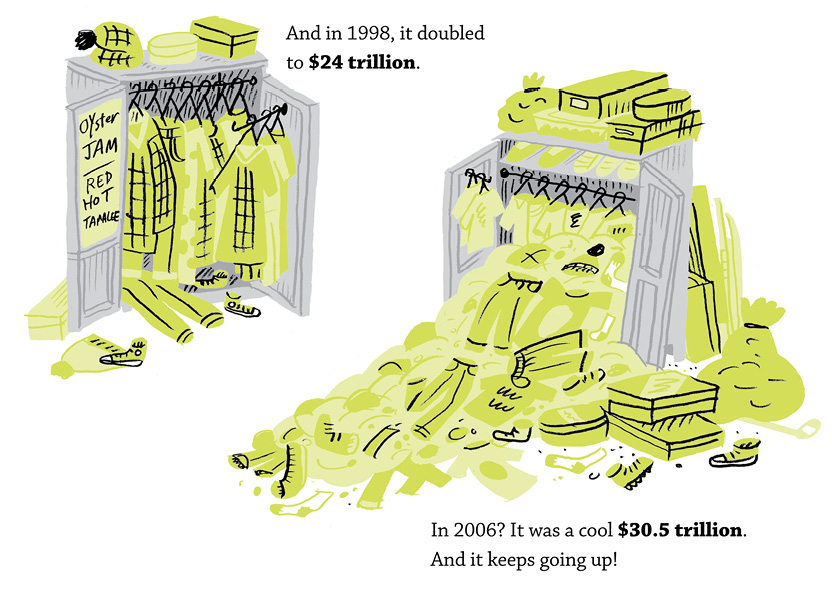

Pretty big numbers, right? But couldn’t the spike in consumption just be chalked up to there being more people and money on the planet? That seems logical, doesn’t it?

Let’s run some numbers. In 1900, there were 1.6 billion people on the planet. In 2006, there were four times that amount: 6.5 billion. So sure, there are more people on the planet with money to spend today, but not over 20 times as many (as in $1.5 trillion x 20 = $30 trillion).

Plus, the places on the planet that have experienced the biggest increases in population during this time are poorer countries where people can’t afford to buy much stuff anyway. In other words, they’re not responsible for this over-consumption boom.

According to the United Nations and World Watch, the U.S. and Canada, with just over 5 percent of the world’s population, are responsible for 31.5 percent of consumption. South Asia, with 22.4 percent of the population, is responsible for 2 percent of consumption. Meanwhile, the poorest 20 percent of the world’s people account for just 1.3 percent of the total global spending by citizens.

What about inflation, you ask? Don’t many items cost more (a lot more) now than they did 100 years ago? True. There’s no question that these rising prices have also had an effect on consumerism rates. But not even the effect of inflation is enough to account for the total spike in growth. Straight up, North Americans buy a lot of stuff.

Nothing as long as you don’t mind the fact that at the current rate of consumption, we’re digging the equivalent of 112 Empire State Buildings’ worth of material every day to make it all. That’s one big bite we’re collectively chomping out of the earth.

The truth is, overbuying isn’t bad only for our wallet—it’s tough on the environment, too.

So how did we end up here? Why do we buy so much? Here are a few of the reasons.

Does your mom hit the road with a cup of coffee in hand while you head off to school? In January 2010, it finally happened: There were more women than men in the workforce in the U.S. (In Canada it happened even earlier, in 2009.) That’s a big jump from 1950, when only one out of every three women worked.

Because more families have two parents bringing home the bacon, they have more disposable income. (And no, “disposable income” doesn’t mean money you can throw away. It’s the money leftover after you pay taxes, silly.) More income means more money. And more money means the ability to buy more stuff, at least as long as the two earners make enough to keep up with inflation.

Now, hold on—no one is saying we should blame girls for wanting to make money. (Hey, if I felt that way this book never would have been written…at least not by me.) Besides, studies have shown that people who work are happier with their lives than those who don’t. Still, the whole two-income reality has an impact on how much we buy.

The result: More money coming into the family means more money can be spent.

The apples in your juice were grown in China. Your shirt was made in Thailand. And Indian factory workers stitched up your pencil case. You’d think with all this whizzing around the planet, these products would cost more in the store, not less. But many companies at home now use companies in countries that pay workers much less than your mom or dad would make here.

The result: Cheaper stuff to buy. So we buy more of it.

Here are just a few bizarre, real-life products out there for you to consider:

Think Thanksgiving turkeys should have more than one wishbone? That little oversight vexed Ken Ahroni, too. Now he’s the president of Lucky Break Wishbone Corp. in Seattle, Washington, a company that makes plastic wishbones that snap!

Here’s an idea: Let’s make goggles for dogs and sell them online! Oh, wait. That’s already been done. Now Doggles are popping up on canine peepers near you.

Speaking of dogs, some people actually pay to slip into a silky coat of dog hair. Fans say dog hair spun into yarn, (a.k.a. chiengora) is warm and repels water. Could that be because it makes you want to shake vigorously after walking in the rain?

$125 for a bar of soap? What’s in it, silver? Actually yes, that’s exactly what Cor silver soap contains. The people who make it say it kills bacteria and makes skin look younger. (Psst! So does regular washing and using sunscreen daily.)

Ah, the credit card. It’s tempting to slap a little plastic card down to pay for groceries, haircuts, and nail polish. They can be really convenient. But that’s the problem. Credit cards can make shopping a little too easy. Studies have actually shown that we buy more stuff if we use a credit card instead of cash.

The result: It seems plastic takes the sting out of spending when you’re paying with it because, well, it doesn’t look like real money.

So now we know why we can afford to buy so much—and that our spending is a tad out of control. Which leads to the next burning question: why do we buy what we buy? Before we find the truth behind that one, I’d like you to meet someone first.

He’s logical by day and rational by night! He only thinks about himself, no matter what! And he doesn’t let his feelings, emotions, or physical pains get in the way of meeting his financial goals of tomorrow! Who is this masked monetary superhero?

He’s Rational Man—the guy traditional economists turn to when they want to determine how people make decisions. Sounds great, doesn’t he?

There’s only one problem: He doesn’t actually exist.

Well, every behavioral economist* on the planet, actually. While more traditional economists assume that people are rational and will always do what’s best for them—like get enough sleep when they’re tired, buy low and sell high, or even pick the best-tasting can of soda—behavioral economists assume only one thing…

People are complex creatures who often do stupid things that make no sense at all. So who’s right? Let’s take a look at some evidence.

* Unlike neoclassical or classical economists—people who study how the economy works and try to predict the future—newfangled behavioral economists are more of a mishmash between economist and psychologist. They look at human behavior as they try to understand how people handle money.

A bunch of researchers headed to a California grocery store and set up a tasting booth. On one day they put out six different kinds of jam. When they returned on other days, they loaded up the table with 24 varieties.

On the 24-jam jar days the table was hopping. So many colors! So much choice! But despite what classic economic theory tells us—that more choice is better for the consumer—only 3 percent of people actually bought a jar that day. And on the six-jar day? A whopping 30 percent of tasters swiped a jar and took it to the checkout counter.

Too much choice isn’t a good thing. It’s just confusing.

It’s not just jam that has us reaching for our wallets when we normally wouldn’t. We spring for all sorts of things we don’t really need. Maybe it’s another sweater when we already have 12. Or it’s a new iPod, even though the old one still spins the digital tunes with ease. And that four-bedroom, five-bathroom mega home? What’s up with that? Does every person (and the dog) need his or her own toilet?

It turns out, most of us don’t even want that much space. Not on a gut level, anyway. That’s what Colin Ellard, an experimental psychologist from the University of Waterloo, found out after he ran an experiment in his research lab. He had home buyers and real estate agents slap on virtual reality headsets and then walk around the school gymnasium.

The headsets were programmed to make people feel like they were strolling through three different houses: one designed by famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright; a cozy, smaller home; and finally a huge new monster home. After these fake tours, the people were asked a bunch of questions that would reveal which home they liked best.

Although many people assumed the big, rich-looking house would take first place, it didn’t. Instead, the comfy house, although small, was the hands-down winner.

“It’s not the size of the house that makes you feel comfortable. It’s the layout and design,” says Colin.

So why are so many new homes built to be bigger than typical families need? Remember, we often think more is better. And don’t forget that little thing called peer pressure. If everybody else seems to be snatching up jumbo mansions, shouldn’t you, too? Turns out the answer is yes—even if it means paying too much money for rooms and space you don’t really need (or even want!).

So our buying habits can be a little kooky. Even a little emotional. How else to explain why your dad comes home with a tub of peanut crunch ice cream when he’s had a bad day at work?

But there’s more. Traditional economics may have been slow to figure out why we spend money, but advertisers have been inside our heads for a long time.

So here’s some homework for you. Check out YouTube and search for old television ads where people are in a blind taste test for Coke and Pepsi. Here’s the gist of them: Without knowing which one was which, the intrepid tasters tried them both and declared Pepsi the winner. It was a big-time commercial that seemed to run for eons all over the world.

The thing is, those ads weren’t lying. For decades, people have actually been reported to prefer the taste of Pepsi over Coke. Still, Coca-Cola continues to be the better seller globally. Even back in 2004, it sold around 4.5 billion cases around the world. Since then, sales have gone way up in countries such as Mexico, Panama, and Romania.

But that doesn’t makes sense, you say? No, it doesn’t. Remember Rational Man on page 58? If people were actually more like him, we would find out which soda pop we like the taste of best, then buy only that kind.

So what’s going on? It’s time to enter the world of neuromarketing, a new science-advertising cross that uses cutting-edge brain research to figure out what makes us buy. This is some “brand” new science.

Relax, no brains were harmed in the making of any commercial. Instead, an American researcher wired up about 70 volunteers to a special machine during a cola taste test. Using the machine, he was able to see what areas of the brain would react as people slurped the sodas. Again, Pepsi was the hands-down winner with more brains displaying the “this feels awesome” reaction on his computer screen.

But here’s the thing: When he tried the experiment again with the labels showing, suddenly a bunch of pro-Pepsi drinkers switched sides to Coke. That time the thinking section of the brain lit up.

What the classic study seemed to prove—and other neuromarketing studies have since—is that brand is an extremely powerful force. In fact, it’s so powerful, it has the ability to make us choose a product we don’t even really like the taste, feel, or look of.

But here’s what we do like: how we picture ourselves using it.

Close your eyes and say these words to your self: Apple. Gucci. Reebok. Notice how the words suddenly became images in your mind? Advertisers spend a lot of time and money giving some gizmo, purse, or running shoe a whole story that they want us to relate to.

Because if that product’s story speaks to us on a gut level, we’re more likely to pony up the cash to buy it.

Given this fact, it’s no wonder advertisers are slapping their brand logos on everything from pencils to banner ads. Because here’s something else they know: people buy the brands they recognize.

For example, take another taste-test study from researchers at Stanford University in the United States. They gave a bunch of kids the same french fries and chicken nuggets wrapped up in different packages. The ones offered in McDonald’s wrappers got the biggest thumbs-up. Remember, same food, just a recognizable brand—a brand millions of people love and trust. Those feelings go a long way.

Believe it or not, spending is not the only way that money can bring us a happy rush. Researchers from Chinese and American universities discovered that merely thinking about money and handling it is enough to make us feel better.

In one experiment, the team asked some people to count eighty $100 bills. Other people counted eighty worthless pieces of paper. After both groups played a video game designed to make them feel crummy about themselves, the participants who counted the real McCoy were still feeling relatively groovy.

Not only that, they even reported feeling less pain when their fingers were plunged in hot water for 30 seconds. Eek!

Sorry to be the one to tell you, but advertisers have got you pegged, and they’re totally after your money. Kids between the ages of eight and 14 (all, say, 20 million of y’all in the U.S.) have got serious spending power. Not only do American tweens—I hate that word, too, but bear with me—walk around with an average of $9 spending money a week, but their parents are out buying stuff for them, too.

Exactly how much money is being spent is tough to pin down, since there are quite a few numbers floating around. But one company, 360Youth.com, reports that

Girls are especially prized by advertisers and marketers, since they’re the ones spending the most money or convincing Mom to open her wallet. In fact, some experts say that girls are the most powerful consumer group since the baby boom. To reflect this demographic switch, there’s been a shift in the ad industry over the past decade, too. A bunch of new companies are springing up saying they’ve got the power to turn girl-speak into biz-speak.

And just check out these book titles: The Great Tween Buying Machine: Capturing Your Share of the Multi-Billion-Dollar Tween Market, or What Kids Buy: The Psychology of Marketing to Kids. Any way you look at it, advertisers know an opportunity when they see one.

All this attention has been enough to warrant launching stores and services aimed specifically at you. Build-a-Bear, Paint Your Own Pottery, and American Girl are just a few examples of these original retailers. Meanwhile, companies with massive kid appeal, like Disney and Nickelodeon, have been known to offer cellphone ringtones for the wave of “starter phones” on the market for kids and teens.

But is there anything actually wrong with making stuff specifically for kids to buy? On one hand, no, of course not. Who wants to wear clothes that look like something a mom would wear?

The problem is, advertising isn’t about making stuff for kids, it’s about selling stuff to kids. And sometimes what advertisers are selling is just a bunch of hot air.

Last week you wanted a new bike. This week you can’t stop thinking about that commercial you saw on TV. Welcome to the cycle of wanting and spending—economists call it “the hedonistic treadmill.” This is what it looks like:

Take labels on clothing, for example. Those labels have a lot of power because advertisers spend time, energy, and money to make sure they tell a story. Remember what you just read a few pages back about brand? Same idea. Apparently, some stories are worth more than others.

Gracie Cavnar

Recipe for Success Foundation,

United States

She’s been a model, architect, businesswoman, and mom. But it was a little newspaper article that turned Gracie Cavnar’s life topsy-turvy and made it go in a whole new direction. The 1996 article mentioned that Texas schools were putting in pop machines, and Gracie, who had also spent years in the marketing business, knew she had to stop them.

“I knew exactly what the junk-food manufacturers were doing,” she says today. “A five-year-old is a very inexpensive get. If you start drinking Pepsi at five, you’ll be drinking Pepsi at fifty. It will cost a fortune to get Coke to convince you to switch when you’re older, but it costs nothing to hook a five-year-old.”

Today she’s not only convincing schools to give up sugary drinks in the halls, but also running the Recipe for Success Foundation, which teaches students how to grow, cook, and then eat their own food. She’s even launching Hope Farms, a 100-acre organic farm in downtown Houston—the largest city farm in the world!

“We do what we can to empower kids’ taste buds,” she says. No cola, or advertising, required.

Let’s compare two pairs of jeans, okay?

What do you think? The more expensive jeans are way cooler, right? They’re probably even more well made. But what if I told you they were put together in the exact same factory, using the exact same materials, by the exact same people? The only difference: that label stitched onto the back. (Which apparently is worth $55. Yup, 55 smackeroos.)

True story. I used to work at a moderately expensive clothing store that sold clothes and underwear to girls and women. We had nice lighting, pretty decor, and a lot of staff to help customers out. And it turned out we sold a few pieces of clothing that were exactly the same as clothes in other stores in the mall. Side by side, you’d never know the difference. You would have had to look in the neck hole to find the label in order to suss out which store made which garment.

The first time I stumbled across a shirt like that, I couldn’t believe it. The el-cheapo store down the hall was hawking it for about $30 less than we were! Was there a catch?

It turns out that when buyers (the people who help decide what stores will sell each season) go to purchase merchandise, they’ll often go to the same sellers or factories as other buyers. And they’ll sometimes pick the same shirts, pants, or other products. Then, in many cases, stores will pay the factory to attach their own labels before shipping them to their warehouses.

So how does a company decide whether to charge $32 or $87? Here’s the short answer: they’ll try to charge whatever we’re willing to pay. Sometimes that tactic works for them. The items fly off the shelves no matter what. (Remember the Apple iPad?) Sometimes it doesn’t and the store has to mark the items down on sale.

Still, there are a lot of different factors that go into price-point decision making.

Maybe the company pays staff a little better than others in the industry and offers lots of training, or maybe they shell out a lot of dough to make the stores look nice. They’ll probably need to jack up the prices on their products to pay for that. At the same time, these companies know that if they improve lighting and make sure their stores look neat and inviting, customers will assume the product is better, too, and they’ll pony up the cash to pay for it.

Then there’s the price itself. It turns out that many consumers assume a high price means the product is better than the lower-priced one. It’s a weird but effective circular argument: “Charge more and they’ll pay more, so you can charge more.” (I know, it hurts my brain, too.)

Your parents might come across this issue at the dinner table tonight if they crack open a bottle of wine. That’s because numerous studies have shown that people don’t necessarily enjoy expensive wine any more than they do a cheap bottle—they only think they do because it’s more expensive. In fact, one study that looked at 6,000 blind tasting results found that people, on average, enjoy pricy wine slightly less!

Another study conducted by the California Institute of Technology and Stanford’s business school looked at adults’ brain scans when drinking two glasses of wine. The researchers were examining the brain’s pleasure center when the subjects took a taste from each cup, thinking one was filled with $90 wine and the other filled with $10 wine. But here’s what the subjects didn’t know: The wines actually came from the same cheap bottle. When the people sipped from the “expensive” cup, more blood and oxygen rushed to the medial orbitofrontal cortex—a decision-making part of the brain. People were analyzing it more thoroughly, looking for the improved flavors. But nothing at all was different between that glass of wine and the other. Just the imagined price.

So what does this all mean in the end? Is shopping a lot of fun? Absolutely. I’m a fan, too.

But it pays to think about what you’re spending money on and why the next time you’re itching to part with some cash at the checkout counter. You might decide there are there are better things to spend your money on.