FOUR

METAMORPHOSIS

VLADIMIR NABOKOV MAY BE THE MOST FAMOUS lepidopterist of the twentieth century. Many people know him for his novel Lolita; college English majors have a broader appreciation of his work; entomologists still talk about his reclassification of North and South American blues. Nabokov wrote twenty-two scientific papers, discovered a few species, and worked for six years as a fellow at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. Some of his research on butterflies was seminal; but his greater legacy is how he wrote about butterflies, how he conveyed his passion, which he called his demon, to the nonpassionate, bemused, but still willing-to-be-entertained world.

“It is astounding how little the ordinary person notices butterflies,” Nabokov marveled, and he set about moving that mountain, not out of altruism but because he had no choice: He was a writer who noticed butterflies all the time.

In a lecture he delivered in the 1950s at Cornell University, by way of discussing Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis and Robert Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Nabokov was sidetracked by the transformation of a caterpillar. His sympathies were with the larva’s growing discomfort, that “tight feeling” about the neck, the imminence of public implosion and disgrace.

“Well,” Nabokov began,

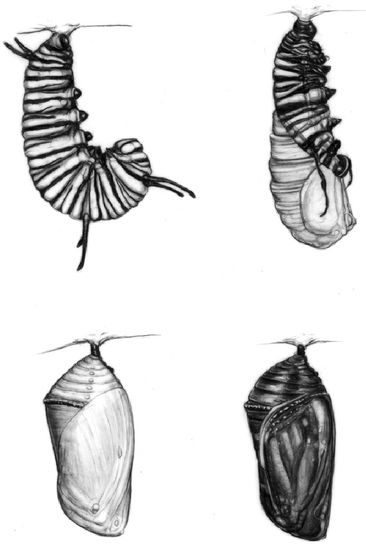

the caterpillar must do something about this horrible feeling. He walks about looking for a suitable place. He finds it. He crawls up a wall or a tree trunk. He makes for himself a little pad of silk on the underside of that perch. He hangs himself by the tip of his tail or last legs, from the silk patch, so as to dangle head downward in the position of an inverted question mark and there is a question—how to get rid now of his skin.

Nabokov described the condition of the prepupal caterpillar, hanging upside down for hours at a time before it makes the final bid for pupation. At last, there is a wiggle, a working of the “shoulders and hips.”

“Then comes the critical moment . . . the problem now is to shed the whole skin—even the skin of those last legs by which we hang—but how to accomplish this without falling?” The professor paused. We can imagine his literature students, puzzled, not quite transfixed.

“So, what does he do,” Nabokov repeated,

this courageous and stubborn little animal who is already partly disrobed? Very carefully he starts working out his hind legs, dislodging them from the patch of silk from which he is dangling, head down—and then with an admirable twist and jerk he sort of jumps off the silk pad, sheds the last shred of hose, and immediately, in the process of the same jerk-and-twist-jump he attaches himself anew by means of a hook that was under the shed skin on the tip of his body. Now all the skin has come off, thank God, and the bared surface, hard and glistening, is the pupa.

Other entomologists have noticed this admirable twist (mainly used in two families, the brush-footed and snout butterflies): that moment as the crowd sits silent and the acrobat hangs suspended from swing to swing. Then the hook locks securely into place.

There is no safety net, which may be why most caterpillars, among them swallowtails, whites, and sulphurs, first spin a silk girdle that connects them to the surface of the wall or twig. Some larvae dangle from their heads, not their tails. Skippers sew together a shelter of leaves. Apollos make a loose cocoon.

The skin has come off, and the bared surface, the hardened chrysalis, or pupa, underneath is a vague, irregular oval. It may have hairs, horns, spines, or honey glands to feed friendly ants. Some features of the developing butterfly inside the chrysalis can be recognized in its shape: the wingpads, the curve of the thorax, the thrust of the abdomen. Most species have distinguishing details.

The chrysalis of the Monarch, who forms the inverted question mark, looks like a jade earring. Near the light green top, an elegant band of gold is underscored with a thin black line. More highlights of gold decorate the bottom half. The pupa of the California Sister, similarly shot with gold, or the Dimorphic Bark Wing, with a silver oval on its dark green thorax, can also be described as jewelry. No one fully understands the purpose of this glitter. Perhaps the pupae gleam to warn off predators. Perhaps their reflectance camouflages them in the light and dark of a sunlit branch. They may be trying to look like metallic beetles. They may be imitating raindrops.

Other boldly colored pupae are the bluish white Baltimore Checkerspots with their orange bumps, black dots, and dashes. The chrysalides of some butterflies in Australia are a startling bright orange. A species in Costa Rica is described as chrome-colored, like small car mirrors, with the wingpads edged in red.

Monarch metamorphosis

But these are exceptions, for the fortunate and the bad-tasting. To a bird or lizard, most pupae are a convenience food: nicely packaged, immobile, full of nutrients. They are the original energy bar.

So the chrysalides of the Zebra butterfly look like brown, drying leaves; and those of the Painted Lady, flakes of rock. The pupa of the European Orange-tip can be mistaken for a thorn growing from a twig.

In some species, in an individual prepupal caterpillar, the background color determines the color of the chrysalis: green for a green surface, brown for brown.

The pupa is carefully choosing its dress.

The pupa is playing a waiting game of hurry up. Sometimes it jerks its abdomen at the threat of a predator. Sometimes, in some species, it makes a clicking sound by using a file of teeth against an armored plate. Some pupae can hiss or squeak or give a vibrational pulse to warn away attackers or to signal ants. The pupae of skippers in the roots of yucca trees move up and down, awkwardly, in their long burrows.

But mostly the pupa is silent, still, intent.

What is it doing, exactly?

Many of the changes started taking place before pupation. The wings of a butterfly begin as early as the first larval stage, or instar, as thickening cells in the thoracic segments. These cells become two pouches called wing buds, or imaginal disks. By the last stage, the fifth instar, each pouch has folded in upon itself to make a four-layered structure corresponding to the future upper and lower surfaces of the adult wing. A pattern of veins is established. A blueprint of the wing is forming, down to the smallest eyespot.

Other adult structures have also started to grow underneath the larval skin. After the caterpillar finds its resting spot, as it hangs in its prepupal stage, these new adult parts—the antennae or the proboscis for sucking up nectar—move to the surface. The caterpillar’s color may change. Swallowtails turn brown.

By the time, as Nabokov sighed, “all the skin has come off, thank God,” and the hard bared surface is revealed, the work of metamorphosis is largely done.

In the first half of pupation, the wing disks grow until they are the size of adult wings confined into the small space of the chrysalis, their surfaces compressed, like a rubber balloon not yet inflated. The scales on the wings develop. Pigments are synthesized to fill in the waiting design. It’s a paint-by-numbers set. Just before emergence, the final touches are added.

In a Buckeye, the rings around the eyespots are colored yellow.

From the beginning, cells in the caterpillar have been preparing the way, genes flicking on and off. Here, at last in the hardened pupa, they resemble a thousand pinball machines. Bang, clang, rebound! This is pinball wizardry, chaos controlled, nothing random. The simple larval eyes dissolve. The butterfly’s complex compound eyes grow from other cells. Legs lengthen and add segments. New muscles develop, some for flight. The huge, dominant stomach shrinks. The sexual organs appear. Eggs may mature in the female, sperm in the male.

Whistle, flash, ring! Everything is rushing, propelled to the right place at the right time to do the right thing. Cells die and are reabsorbed, cells divide, cells restructure. You’re a winner!

The time spent in the chrysalis, from liquefied caterpillar to adult butterfly, varies in different species from days to weeks.

In climates that get very cold or very hot, the pupa may delay its transformation and hibernate during the winter or summer months. Some pupae can wait for the right signal, whether warmth or rain, for five to seven years.

A bag of goo crawls on a leaf, obsessed with eating. It hangs upside down. It becomes something else. A butterfly is born, a bit of blue heaven, a jazzy design.

It is a gesture of beauty almost too casual.

We are storytelling animals. The peak is high and white with snow. Who has not seen God in the mountains?

Do we create the story or resonate with it?

The story of the butterfly has been read the same by people around the world.

When the Hindu god Brahma watched the caterpillars in his garden change into pupae and then into butterflies, he conceived the idea of reincarnation: perfection through rebirth. The Greeks used the word psyche for butterfly and for soul. Ancient images on Egyptian tombs and sarcophagi show butterflies surrounding the dead. In the fifth century, Pope Gelasius I made a pontifical declaration comparing the life of Christ to that of the caterpillar: Vermis quia resurrexit! The worm has risen again. In Ireland, in 1680, a law forbade the killing of white butterflies because they were the souls of children. In Java, in 1883, a migration of butterflies was interpreted as the journey of the 30,000 people killed by the eruption at Krakatau. In China, in the 1990s, single white butterflies were found in the cells of executed convicts recently converted to Buddhism.

The butterfly is a human soul. What could be more obvious?

After World War II, Elizabeth Kubler-Ross visited the barracks of a Polish concentration camp and saw hundreds of butterflies carved into the walls by Jewish inmates. “Once dead, they would be out of this hellish place,” she wrote. “Not tortured anymore. Not separated from their families. Not sent to gas chambers. None of this gruesome life mattered anymore. Soon they would leave their bodies the way a butterfly leaves its cocoon.”

Miriam Rothschild saw the same image drawn with orange chalk in Jerusalem: “It was a butterfly every Jew and Jewess knows by heart, the butterfly drawn by children in German death camps before they went to the gas chambers. Fifteen thousand children had been incarcerated in one particular camp; only a hundred survived. It is the emblem of escape from the greatest sorrow the world has ever known.”

Butterflies, death, resurrection. Besides the Victorian collectors, few cultures have been as obsessed with butterflies as the nobility of ancient Mexico, the people who turned ritual sacrifice into a state-sponsored art form. On the first day of each month, hundreds of Aztec subjects—children, captives, and slaves—were killed. On special occasions, thousands died.

In the sixteenth century, high-ranking Aztecs carried bouquets of flowers. Everyone knew that it was impolite to smell these flowers from the top, since that was reserved for butterflies, the returned souls of warriors and sacrificial victims. Toltec and Aztec shields were often decorated with butterflies, possibly a reference to the goddess of love, Xochiquetzal, who held a butterfly between her lips as she made love to young men on the battlefield. Her kisses were their assurance that they would be reborn if they died that day.

Xochiquetzal was the mother of Quetzalcoatl, the god of life, who suggested that the Aztecs offer tortillas, incense, flowers, and butterflies instead of human hearts ripped from living chests. The idea never caught on. In a single celebration, the Aztec ruler of Tenochtitlán once sacrificed 10,000 prisoners, marching them up temples awash in blood. Theoretically, the victims may have all become skippers, swallowtails, Monarchs, and Madrones.

From what we know about a caterpillar’s life, the idea of war and sacrifice juxtaposed with butterflies is not unreasonable. Entomologists deal in the archetypical symbol of spiritual transformation. They are rarely sentimentalists.

A common experience for anyone collecting butterflies is to keep watch on a chrysalis, in happy expectation, only to see a parasitoid emerge, usually a wasp or group of wasps.

As Philip DeVries pointed out, “Incidentally, it is during the noticeable wandering phase that many casual entomologists take note of caterpillars and subsequently confine them in containers.” At this point, he added, it is just as likely that something else has found the caterpillar first.

It happened to me once. I was eight years old. My third grade classroom stood next to a large group of trees, possibly mulberries, which erupted in the spring with teeming nests of caterpillars, possibly silkworms. Rumor had it that our teacher once punished a child for keeping a caterpillar by cutting it in half with her yellow ruler. I rushed my caterpillar home and put it in a shoebox with lots of mulberry leaves. You can imagine my delight when it spun a cocoon.

Later, when the cocoon broke open, you can imagine my dismay.

All this underscores the miracle of what can and does happen regularly. The caterpillar forms a question. The question is answered when a Queen, cousin of the Monarch, emerges from her chrysalis just before dawn with a swollen-looking body and pathetic, wet, crumpled wings.

She needs gravity to help her, and so she climbs to where her wings can hang down as she pumps blood through their veins to expand and harden them. She needs to dispose of waste products, too, and she emits a brownish red fluid. She needs to remove dead cells and skin from her antennae. She needs to zip together the two halves of her proboscis so that it will function as a perfect drinking straw.

Tentatively, she moves her head and thorax, which are beautifully patterned, white spots on black. Small bumps, or palpi, near her clubbed antennae may be used later for cleaning and brushing. Her thorax and abdomen are her toughest parts, capable of being grabbed, tested, and rejected by a predator. Like all insects, she has six legs; on her, the front pair are reduced.

Perceptibly, second by second, she gains strength. Her large wings are a russet orange with a black scalloped border. The top pair are called forewings; the lower pair are hindwings. She moves in place, lifting her legs, weighing perhaps a third of what she weighed as a caterpillar.

Once she was a stomach attached to a mouth. Now she is designed to float through the air.

Her old obsession was food. Her new obsession is mating and laying eggs.

In an hour or so, she is ready to fly away.

Vermis quia resurrexit!