ELEVEN

THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM

THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM IN LONDON, which holds one of the world’s largest and oldest butterfly collections, looks like a cathedral. The entrance is massive, patterned in fawn and blue-gray stone, with rows of arched windows and rising pinnacles. Inside, stained glass spills light onto the central nave, or “sacred space,” which opens into smaller “chapel areas.” The high ceiling is decorated with green and gold illustrations of plants identified by their scientific names: Digitalis purpurea, Rosa canina, Daphne laureola. The sacred space is filled with the replicated skeleton of the dinosaur Diplodocus, the bones and the air between bones of a plant-eater who measured eighty-five feet from head to tail. The chapel areas showcase fossils, the mystery of what has been and will never be again.

This church crawls with animals, molded and cast in terra-cotta on leafy panels on every wall: warthogs and owls, foxes and sheep, pigeons and stoats. Snakes entwine pillars. Monkeys climb doors. A lizard creeps toward the exit sign. The west half of the building highlights living species, the east half-extinct ones.

The museum’s marriage of religion and biology began with its first donor, Sir Hans Sloane, whose private collection formed the basis of the British Museum in the 1750s and later the splintered-off British Natural History Museum in 1881. Sloane’s will expressed the hope that the study of his natural oddities would result in the higher study of God. The first superintendent of the natural history department was Richard Owen, the man who coined the word dinosaur, a creationist in fierce opposition to Darwin’s theory of evolution. Owen also believed that the museum’s purpose was to display Divine Will. With the help of the brilliant architect Alfred Waterhouse, he created a building designed for worship.

For years, a bronze statue of Sir Richard Owen glared across the central hall at a marble Charles Darwin sitting in repose. Today, Darwin looks out virtually unnoticed over a café area serving lattes and fruit tarts. His anonymity seems less banishment than acknowledgment. He’s common as cake, in the air we breathe and food we eat.

Dick Vane-Wright is the museum’s Keeper of Entomology, and his personal secretary is at the reception desk, ready to take me via lifts and locked doors to the hidden kingdom. First we go through the dinosaur exhibit, turning a corner to confront the most realistic robotic Tyrannosaurus rex I have ever seen.

As big as my bedroom, he crouches over the body of a duck-billed Edmontosaurus twitching between life and death. T. rex growls and swings his head from side to side, moving red-stained teeth closer to the low wall that separates us. Bending to sniff his prey, he roars loudly, then rears back with nervous excitement. He is about to rip the flesh from the dying herbivore. Yet, he does not. There is a beat. T. rex growls and swings his head from side to side, moving red-stained teeth closer . . .

London is in the middle of a rail crisis, and Dick Vane-Wright is running late. I am taken, in the meantime, to see Jeremy Holloway, a scientific associate. Jeremy’s office is on the ground floor of a department that goes up and down six floors and contains some 30 million insects in 120,000 drawers. Of those, 8.5 million are pinned moths and butterflies. These include the over 2 million specimens that Lord Walter Rothschild gave the museum in 1937, which were combined with the earlier collections of Sir Hans Sloane and James Petiver. Other collections have been donated or bought, and the museum’s associates, including Jeremy, and John Tennent in the Solomon Islands, continue to add specimens, perhaps as many as a thousand a year.

Jeremy is actually working on moths. He may know more about the larger moths of Southeast Asia than anyone alive, and is currently writing the definitive Moths of Borneo. He stands up to open a drawer. His office is small, more of a carved-out space than an office, on the edge of a cavernous floor area with rows and rows of tall wooden cabinets. The paths between the rows are like the corridors of a maze. The cabinets, many of which were donated by Lord Rothschild, rise above our heads and then spread laterally to a distant wall. Jeremy’s collected specimens, pinned directly into the drawer, are nicely at hand.

And there they are: a line of delicate brown-and-white moths all looking somewhat alike. Jeremy points out the printed label that says “type.” The type specimen is the individual moth or butterfly that has been chosen to represent the species as a whole. These are the dead diplomats of their countries. The Natural History Museum has over half the type specimens of the world’s moths and butterflies. The rest of the series of somewhat look-alike insects shows the variations within a species, comparative to the type, including geographic races.

Because of storage problems, collectors no longer pin the kind of long series they used to delight in. This may be unfortunate. Many of the insects that Jeremy describes in Moths of Borneo are new species. They have been collected before, but when Jeremy looks at these older collections (specifically at the genitalia, an important diagnostic key), he finds in a series of moths not one, but two or more different species.

A large collection such as this is used mainly for taxonomy. In the Solomon Islands, John Tennent swoops down his net to catch a blue butterfly so that it can be compared with all the other blues here, including those swooped by A. S. Meek and other early collectors. These comparisons help determine the butterfly’s family tree, its affinities, and its relationships.

A second use of the collection has to do with biodiversity. This museum is a window onto the butterflies that could have been found in England three hundred years ago, when James Petiver was receiving specimens from Eleanor Glanville; or one hundred years ago, when Walter Rothschild was a boy collecting in his estate gardens outside London; or fifty years ago, when Miriam Rothschild was collecting in the same gardens. In these drawers, we see what we have lost and what we have not.

Jeremy is interested in how moth and butterfly diversity can reflect overall diversity. He believes there is a correlation. He is looking at which moth species exist in different managed landscapes: in a new softwood timber plantation in Malaysia, in an older plantation with a thick understory, and in a primary undisturbed forest.

“When we know what is there,” Jeremy says, “we can go back and keep checking against that record. We can see what is changing. We can see the costs in biodiversity of a certain practice, and maybe how to mitigate those costs. First we need some basic information.”

In a world that has become a garden, with all our landscapes managed, determining the “right mosaic of development” may be as important as conserving patches of wild land.

Moths of Borneo is an eighteen-volume series. Jeremy is on the thirteenth book.

Dick Vane-Wright, Keeper of Entomology, has an office with a view that I fancy includes the treetops of Kensington Garden, made famous in James M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. In 1961, when Dick was eighteen years old, he came to this office to see about a job. Except for leaves to get his degrees and to do research, he has worked for the museum ever since.

John Tennent has urged me to ask Dick about the time he ate insects on television.

Philip DeVries has described Dick as an “unusual and ebullient” classifier of things who, like Phil, is also a former jazz musician. During our talk, the keeper will jump up every so often to fetch this book or that one down from the shelf. He jumps up now to show me the 1885 tract “Why Not Eat Insects?”

“Why not eat insects? Why not indeed!” begins that author, going on to discuss the nutritional, culinary, and economic value of sawflies and wood lice. Concerning the green worm of the Cabbage White butterfly, “I see every reason why cabbages should be served up surrounded by a delicately flavored fringe of the caterpillars which feed upon them!”

The plump bodies of moths are nice when grilled.

And “Let us, then, cast aside our foolish prejudice, and delight in chrysalides fried in butter, with yolk of egg and seasoning, or ‘Chrysalides à la Chinoise.’”

Dick Vane-Wright is almost as cheery. “Eating insects is a challenge of social mores and cultural norms. It’s puncturing people’s pomposity!”

Dick confides, “There is a certain pomp and pomposity to this job, which goes against my grain.”

So when the Natural History Museum decided to reprint the 1885 tract, Dick went on a tour of promotion, crunching locusts over the radio and frying up mealworms on the BBC. For a while, a few London restaurants tried serving insect food. “I had a modest part in that,” the Keeper of Entomology says now.

Ask entomologists how they became interested in bugs and butterflies and three out of four will give you a number.

“I was thirteen years old,” writes Edward O. Wilson.

“Although I lacked an inquiring mind, I was a good observer for my five years,” begins Miriam Rothschild.

“When I was twelve years old,” Robert Pyle, a well-known lepidopterist, remembers.

“I was a child on country walks,” Jeremy Holloway agrees.

“I was a little boy collecting beetles,” David Carter, Jeremy’s colleague, will say.

“I was seven years old,” Dick chimes in, “and I was given a book by some children’s author now much reviled, soft information on natural history, with colored pictures of butterflies. Out in our yard we had a flowering tree and, in my mind now, it seems I was able to match every butterfly in that book to a butterfly on that tree. It was a one-to-one match. Very satisfying.”

Matching things one-to-one, recognizing patterns, finding the thing that does not fit the pattern, naming the pattern, naming the anomaly, checking back with the book, writing the book yourself someday. It is all, indeed, very satisfying. The adult murmurs of biological order. The seven-year-old shouts, “Gotcha!” This surpasses the swoop of a net. In taxonomy, you capture a species.

Biological order today is based on how organisms have evolved through time: the ancestors they share. Dick likes to spend his time unraveling what the colors on a swallowtail or the perfume of a Monarch might reveal about its ancestry and closest relatives. As part of his research in the 1980s, he went to the Philippines, an area rich in butterflies, but already known to be badly deforested.

“I wasn’t prepared for how deforested,” Dick says.

It made a huge impact on the rest of my life. I was so shocked and so convinced that this wasn’t good for anyone, certainly not for the people who lived there. It was a mixture of greed, ignorance, and poverty, destroying an ecosystem and replacing it with nothing at all. I became ill. I thought I was physically ill but, as it turned out, I was mentally or emotionally ill. The problem was fixed when I had to fly to New Guinea to do more experiments on butterfly behavior. The landscape there was magical. I felt immediately better. I had simply, actually, been depressed.

Dick jumps up to look for a book on New Guinea butterflies. He finds, instead, something produced by a Japanese collector. What is happening now to butterflies in Japan?

No one knows.

“Unless we have an idea of what is there and where it is and how to identify it, we can’t take care of it,” Dick echoes Jeremy.

The London museum is now mapping the hot spots of diversity. “In effect, we’re telling people that if you must trash x amount, please don’t trash this part because it will have tremendous impact on how many species can remain in the world.”

As fast as possible, lists of species are being generated: for Asia, for Africa, for Australia, for North America. Dick calls this bioaccounting.

“We’re producing telephone directories.”

What happens when you call a number in this directory? Not much if you are looking for information on how a butterfly lives, mates, reproduces, or dies. Don’t expect a chatty conversation.

“There is so much we don’t know!” Dick says, sounding excited and distressed at the same time. “You could spend a week studying some obscure insect and you would then know more than anyone else on the planet. Our ignorance is profound.”

He jumps up to fetch another book.

In 1984, Phil Ackery, a collections manager at the museum, and Dick Vane-Wright collaborated on two important books, Milkweed Butterflies, Their Cladistics and Biology and The Biology of Butterflies. By 1990, Phil was feeling the need to specialize, to focus on research or on collection management, but not on both. “I landed rather more on the collection side of the fence,” he says today.

Much of his work deals with pest control.

Collectors have long complained about the problems of maintenance. In 1702, Eleanor Glanville wrote to James Petiver:

I being not at home have preserved but few plants this year, and so long neglecting to clean my butterflys being almost 2 years ye mites have done me much mischefe, I have lost above a 100 Species of my finest . . . wch I put up closest and Safest for fear of Spiders and mice. I believe for want of aire, not being fresh, ye mites breed ye more and ye Bettles was molded over with a whit crusty mould wch when I went to clean broke al to peeces. I hope while I live never again to let them be so long neglected.

The Natural History Museum in London is mostly plagued by the larvae of beetles: Anthrenus sarnicus, a gray-and-gold carpet beetle about a tenth of an inch long; Reesa vespulae, the American wasp beetle, the females of which can reproduce on their own; Attagenus smirnovi, the brown carpet beetle; and Stegobium paniceum, the biscuit, or drugstore, beetle. Phil and Dick refer to them generically as museum beetles, of which there is also a specific species, Anthrenus museorum.

Typically, a female beetle living in one of the building’s outside birds’ nests flies through a window to lay her eggs near something that smells good, perhaps a dead insect on the other side of a wooden cabinet. The larvae hatch, worm through the tiniest crack, and begin to feed. A new kind of museum beetle, introduced in the last twenty years, has the destructive pattern of taking a bite from one butterfly and then moving on to take a bite from another, potentially plowing through half the specimens in a case. By now, the beetle itself is too large to escape. A researcher opens a drawer. One dead beetle. Lots of little bits of butterflies.

Phil guesses that at the beginning of each year there might be forty identified infestations in the museum’s 120,000 insect drawers. For a long time, the museum relied on pesticides, until people realized that what was toxic to invertebrates was toxic to mammals, too. In this case, the chemicals were contained under high vapor pressure. When a researcher opened a drawer, the fumes roiled out. Fifteen years later, as I walk past the cabinets, fifteen years after the last dose of Naphthalene, I can smell it still.

Collections now have to survive without insecticide. First, everything is frozen, whatever people send in, whatever the museum buys, at minus thirty degrees Centigrade for seventy-two hours. This kills pests like beetles. Infested drawers also go into deep freeze. Slowly, too, Phil is acquiring “good museum furniture,” not the antique glow of wood but gray steel boxes with tight seals. These boxes are compacted into unaesthetic horizontal units that can be opened manually to a specific site.

Eventually the entire building will have to be hermetically sealed, and people will have to change their work habits. Phil points to a sink in his own slightly cluttered office. “That creates a micro-environment of high dampness. There’s lots of book lice running around a sink like that. Someone comes and places a drawer by the sink and there you are.”

Some of Phil’s clutter involves his most recent project, an exhibit of seventy-three butterfly species collected by Henry Walter Bates. Phil was interested in how Bates had pinned his butterflies and how he had transported them to the British Museum.

Would I like to see?

I am out of the office in a nanosecond, possibly carrying a few book lice with me.

Phil takes the lead through the wooden canyons. He has worked at the museum since 1965 and has written amusingly of those annual meetings in the 1960s and 1970s, attended by prominent lepidopterists, when “the canyons between the cabinets would echo with such triumphant cries as ‘New record for Shropshire!’ always in the well-modulated but irritatingly penetrating tones of what seem to be the primary attribute of a British private education.”

“How did I get interested?” he repeats my question.

Well, I wasn’t one of those people born with a net in my hand. I wasn’t rearing Large Whites when I was three and a half years old. I suppose that for most people working in a natural history museum, the attraction is to the natural history, whereas mine was for the museum part. I quite enjoy ordering things into straight lines and then putting pretty labels on them. It wouldn’t make odds to me whether it was butterflies or flintlock rifles. I’m happy doing things like indexing. I have a good boredom threshold.

We stop before a cabinet. Phil casually opens a drawer.

They are so much brighter than I had imagined they would be. The blue-and-yellow Nessaea batesii. The azure of Asterope sapphira.

Phil believes that Bates set and pinned his specimens in the field and that later, after he had sent them to his agent, they were repinned in another style, slightly damaging the thorax.

Phil shows me a damaged thorax.

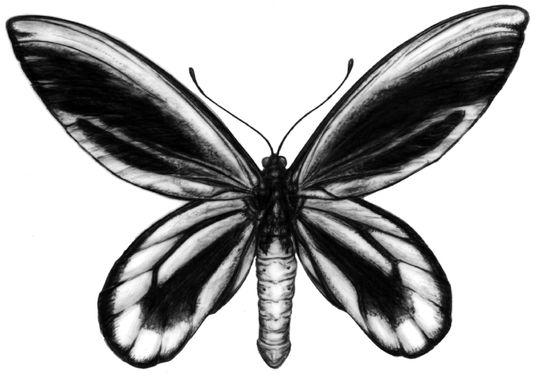

Without my having to beg, he takes me to look at the Ornithoptera, the Queen Alexandra’s Birdwing and the Giant Birdwing, also collected in the nineteenth century. Just a few of these green-and-blue wings fill up the space of a drawer. The yellow abdomens are huge. The green is primal.

Phil points to holes in the wings of certain females. In 1890, one collector wrote of seeing such a birdwing while bathing; he scrambled from the water, seized his net, and ran through the jungle naked: “I tread upon a sharp stone and fall head over heels, but picking myself up again, continue the chase along the beach, till at last, just as my quarry is rising among the trees, I come up with it, and by a well-directed stroke enclose it in the net. I leave it to any ardent entomologist to imagine my feelings on this occasion.”

Later, the happy nudist “saw several more but as they kept high up among the trees I thought I would try to shoot them with dust-shot. I was carrying a 16-bore gun, into one barrel of which a Morris tube .360 bore was fitted, and by its aid I shot two more females.”

Queen Alexandra’s Birdwing

Phil closes the drawer, rolling the birdwings back into darkness, like jewelry hidden away. He has to return to work, and he tells me that I can wait for David Carter, another collections manager, at a table here, at the end of this corridor, under the canyon walls, not far from the butterflies collected by Henry Bates. It’s been fun, Phil says. Ta-ta.

I can’t believe they trust me, alone.

I sit at the table, waiting for David Carter.

Then I stand up and sneak to the nearest drawer.

I open it slowly, trying not to make a sound. Slowly, I reveal rows of spotted green and spiraled red, creamy forewings, chevroned hindwings. I leave the drawer open and move to another.

Camberwell Beauties. The gorgeous Peacock. The Tortoiseshell.

I tiptoe down the wooden canyon, open two more drawers, three more, five more, an Owl, a Zebra Longwing, a Red Admiral. I leave them all open. The butterflies begin to stir, pushing their wings against the case, moving up, bright ghosts, through the glass into the air.

I open more drawers, and more. The room fills with butterflies, series of Checkered Whites and blues, Tiger Swallowtails, clearwings, metalmarks, Snouts, Ornithoptera. One Grayling bows to another. Two sulphurs begin to mate.

There are tropical cries, parrots and monkeys. There is the scent of jasmine.

And then I am back at the table, looking innocent.

David Carter finds me waiting. We talk about how old brass pins can suddenly implode an insect’s body in a reaction of temperature and pressure and fat. He tells me about creaking cabinets and the sounds they make at night when he is working here alone. Sometimes the wood splits like a pistol shot! We talk about research and a recent request from scientists who wanted to run DNA tests of butterflies collected long ago. They wondered if the museum “could spare a leg.”

We wander into the collection, up and down stairs, and I confess, “I still don’t know where I am going here,” and David agrees, “Oh, it was years before I knew where I was going.”

Then he is using his keys to open up a gray steel cabinet. This is the collection from Sir Hans Sloane, who in the early 1700s bought James Petiver’s collection. Sir Hans was so appalled by Petiver’s “bowerbird’s mentality,” the shelves of objects helter-skelter, that he immediately hired someone to conserve the specimens. I am looking now at three-hundred-year-old sulphurs pressed between sheets of thin clear mica. The sulphurs still glow with the incandescent color that gave them their name.

Somewhere here is the fritillary that Eleanor Glanville sent her friend and mentor, after her second husband left her in peace, before he kidnapped her son and threatened her other children, before she began to confuse her children with fairies. The Glanville Fritillary, never common, remains rare, confined to a small area off the south coast of England.

And there is more, even before Petiver, a collector who pressed his insects, like flowers, between the pages of a book. David Carter, already enthused, is sparkling now, generating excitement. This may be the oldest insect collection anywhere.

Surely David has done this before, many times, first showing the visitor photographs of what is inside the book, a pressed Tortoiseshell, a Peacock, and then showing the book itself. But, of course, not opening it. Every time the volume is opened, more damage is done to its fragile contents. Of course, we cannot open the book. We can only gaze at its cover.

Surely David has done this before, yet his interest seems as keen and fresh as these butterflies, remarkably still alive in their drawers. It is David’s obsession, and Dick’s and Phil’s, to keep this collection keen and fresh for another three hundred years. It is a remarkable continuum and a singular statement that goes beyond naming, beyond ownership, beyond order. It is the shape of history: stories and time.

A man runs naked through the jungle. A man leaps, ardent, a net in his hand.