The most unusual thing about Mister Morris was the fact that he was missing a leg. It got blown off when he was a soldier a long, long time ago. He’d been sitting in a trench in the middle of nowhere when a shell came screaming out of a clear blue sky. The same terrible shell that blew Mister Morris’s left leg off also killed his best friend Frank. One minute they were crouching in their trench, talking about cricket, the next minute young Frank was dead.

After the war, Mister Morris got a job in a hardware shop, selling screws and glues and nuts and bolts. If someone was hanging a door, he’d tell them what sort of hinge they needed. If they were putting up a shelf he’d tell them which brackets to buy. Whenever a customer bought a light bulb Mister Morris would insist on checking it. He’d slip the bulb out of its cardboard sleeve and twist it into a socket behind the counter. If it lit up he’d say, ‘That’s a good ’un.’ If it didn’t (which wasn’t very often) he’d say, ‘That’s a bad ’un,’ and throw it in the bin.

For forty-two years Mister Morris sold bottles of turps and methylated spirits and gave his customers advice on brushes and bradawls and brooms. He spent all day hobbling about the shop on his wooden leg (which had a shoe neatly fastened to the end of it), without uttering a single word of disgruntlement. He was a popular man – a mine of useful information. And when he finally retired the other members of staff took him out to dinner and gave him a watch for his waistcoat pocket, with an inscription which read, ‘Time to put your foot up, old son.’ At the end of the night Mister Morris shook hands with his old colleagues and hobbled off down the street. But when he woke on the Monday morning he decided that he was going to need a project to keep him occupied.

For some people, retirement can be a bit of a shock to the system. They suddenly find they have far too much time on their hands. Some stay in bed, trying to catch up on all the sleep they think they’ve missed out on. Some study. Some watch daytime TV. But it can be hard changing the habits of a lifetime. They wake up early, even though they didn’t set the alarm. They miss the old routine. And the days can sometimes seem to stretch out before them like an empty, friendless place.

Some people miss the company of their old work-mates and begin to wish they’d never left their job. Mister Morris felt no such thing. But he knew he needed something to keep him busy, and began to wonder what sort of project he should set himself.

Every morning of his first week of retirement he made a pot of tea, boiled himself an egg, then walked along the river which wound its way right through the town. He could write a book, he thought. A book about working in a hardware store. Or maybe a book about the war.

He liked cycling. Perhaps he could cycle from one end of the country to the other. He went to the library, to find out how many miles it was from Land’s End to John-o’-Groats, but, having found out, suddenly felt that perhaps it wasn’t such a good idea after all.

He could take up fishing. He was very fond of fish – especially when they had a few chips beside them – but didn’t relish the idea of sitting around all day waiting for them to swim along.

On the Thursday morning Mister Morris was standing on the riverbank, watching the water quietly sliding by. He knew he was getting close to thinking up an interesting project. He could feel it in his bones. He remembered a holiday when he was a boy. His father hired a boat and rowed young Mister Morris and his mother out on Lake Windermere.

The idea lit up in his head just like a light bulb. He would build himself a rowing boat.

‘That’s a good ’un,’ he said out loud.

Mister Morris turned and hurried home. He went straight down into his cellar, where all his saws and hammers stood to attention along one wall. He stood beside them and wondered what sort of boat to build himself. He could build a kayak, he thought, like the Eskimos paddle themselves around in. Or some other type of canoe. He tried to think of all the different boats he’d ever come across. He quite liked the idea of building a coracle (if only because he liked saying the word) but in the end he settled on an old-fashioned row-boat, like the one his dad had hired sixty years earlier. It seemed like the sort of boat most fitting for a man his age.

He drew up some plans, worked out how much wood he’d be needing and paid a visit to the timber yard. And for the next couple of months he rose early, had a decent breakfast (cereal … toast and honey … pot of tea), then went down into the cellar and put his overalls on. He worked steadily right through the day, emerging around one o’clock for a light lunch (soup … cheese and pickle sandwich) and around three or four for another pot of tea.

In the evenings he walked along the bank of the river and imagined himself rowing up and down it. He pictured himself rowing upriver to a country pub and sitting and doing the crossword; pictured himself rowing downriver to visit the hardware shop.

Mister Morris liked the smell of sawdust. He liked the feel of the wood after the sandpaper had smoothed it away. Most of all, he liked the smell of the varnish. By the time that boat was finished, it must have had about ten coats of the stuff brushed onto it. It was as brown as a kipper and had the same treacly glaze to it as that boat on Lake Windermere.

He finished the oars and gently placed them in the rowlocks. He stepped back to admire his work. The boat sat on its trestles, like something in a museum, and Mister Morris felt enormously proud of himself. He thought of all the care he’d taken in the boat’s construction. All the sweat that had soaked into his shirts. But even as he stood there admiring his beautiful boat he felt a strange chill creep across his shoulders, as if something awful was about to come to pass.

He looked at the boat – so big and strong and solid. Then he slowly turned and looked back up the stairs. The cellar door seemed suddenly small. He looked back down at the boat. His mouth dropped open. And bitter tears welled up in his eyes.

For a while Mister Morris sat in his kitchen and pretended to listen to the radio. He couldn’t stand to see his mighty boat trapped down below. After about an hour, he went back downstairs, found the tape measure and did some calculations on the back of an envelope. But whichever way he came at it, he couldn’t find a way of squeezing such a sizeable boat through such a narrow door.

What upset him most – more than all his wasted effort – was the fact that the boat was now unable to do what it had been specifically built for. It was imprisoned, like some poor wretch locked up in a dungeon, far away from the water on which it had hoped to sail.

In the weeks that followed, Mister Morris did his best not to think about it, whilst actually thinking about it a great deal of the time. He went to the shops, cooked his dinner and listened to the radio but kept finding himself down in the cellar, staring at his stranded rowing boat.

One Wednesday evening he was walking by the river when he noticed how high the water was getting. There had been a lot of rain lately (which was not that unusual) and he thought no more about it until he was woken in the middle of the night by the sound of people shouting in the street. He stuck his head out of the window. All his neighbours were standing around in their pyjamas and wellingtons.

‘It’s the river, Mister Morris,’ one of them called up to him. ‘It’s burst its banks.’

Mister Morris closed the window and hopped back into bed. He sat there for a couple of minutes, thinking. Then he strapped his wooden leg on, found his dressing gown and went down the stairs.

When he opened the door to his cellar he was confronted by a scene that both horrified and delighted him. Cardboard boxes and tins of varnish were floating in three feet of water. Jars of screws and bottles of beer were bobbing about the place. And in their midst, looking serene and stately, drifted Mister Morris’s rowing boat.

He made a lasso out of a bit of old washing line, twirled it above his head once or twice and threw it in the direction of the boat. Then Mister Morris slowly drew his row-boat towards him, like a rancher drawing in some wild-eyed horse. He gently eased himself off the stairs on to the boat’s broad cross-bench and, once he was settled, carefully pushed himself away from the stairs. And for the rest of the night Mister Morris rowed blissfully back and forth between the walls of his flooded cellar, through all the flotsam and jetsam of his life.

It wasn’t much, but it was better than nothing. At least he got to practice how to do his turns. Most of his neighbours spent the next few days standing around complaining and saying how they’d never get over it. Meanwhile, Mister Morris was down in his cellar, finding his sea legs, and might well have slept in his precious boat if he hadn’t thought it would be a bit uncomfortable.

By the Thursday afternoon it had more or less stopped raining and, not long after, the water level began to fall. Mister Morris rose early on the Saturday morning, hoping to squeeze in another couple of hours’ rowing, but opened the cellar door to find the boat (and all his bits and pieces) beached in several inches of mud.

It was a horrible mess, but Mister Morris rose to the challenge, and as he scooped up the mud and wiped down the walls he was already looking forward to the possibility of other, even more disastrous floods. From that day forward every drop of rain would lift his spirits. Every black cloud would give him hope. He kept a close eye on the river but it never really looked in any serious danger of coming over the top.

He decided to think ahead. It seemed highly likely that the river would flood around the same time the following year. If he could create a little more space in his cellar he would have more room to row about. So he embarked on a year-long programme of earth removal. He bought a pick and a brand-new barrow and started hacking away at the cellar wall. His first tunnel was five foot high and six foot wide and headed out under the street, where it soon came up against all sorts of drains and pipes and other obstacles. So Mister Morris started a second tunnel, which headed under his back garden, and on this his progress was both swift and sure.

He supported the tunnel roof with odd bits of timber he’d picked out of skips. On a typical day he might spend four or five hours tunnelling, then sleep for an hour or two. He would cook himself some dinner, then wait until nightfall. And in the early hours of the morning he would carry the buckets of earth up the stairs to his waiting barrow and wheel it off down the moonlit streets.

On the first few nights he dumped the earth in his neighbours’ gardens but it was clear that there was a limit to how long he could get away with that. So he wheeled his barrow down to the river and tipped the soil into the water, where it sank without a trace. This was a much more practical way of going about things. Mister Morris thought that in time it might even help to raise the water level by an inch or two. Nobody seemed to mind an old man wandering around the place with a wheelbarrow after bedtime. A town’s streets are surprisingly quiet between the hours of three and four a.m. Only once did Mister Morris have any trouble, when a police car pulled up alongside him as he emptied another barrow-load of earth into the river.

The policeman wound down his window and shone a torch into Mister Morris’s face. He asked Mister Morris if he’d mind explaining what he was up to.

Mister Morris looked down into his empty barrow then back up at the policeman. ‘I’m retired,’ he said.

The policeman took a moment to chew this over. His own father had retired a couple of years earlier and was for ever getting up at half past five to do the hoovering. The policeman told Mister Morris to make sure he didn’t wake anybody up whilst he was about his business. Then he wound his window back up and drove off into the night.

Progress continued at a steady rate. Five months after he first started Mister Morris estimated that the tunnel was approximately a quarter of a mile in length. If he could keep on at the same sort of pace he reckoned he’d be out of town and under Birch Hill by the time the rain came round again.

About a month before the floods were expected Mister Morris tied his boat to the bottom banister to stop it being swept away. He grew more and more excited but one Tuesday night, after a hard day’s digging, he was walking alongside the river when he noticed some activity up ahead. He got a bit closer and saw a dozen soldiers standing in a line between a lorry and the river, passing sandbags from man to man.

Mister Morris suddenly felt quite sick. He approached one of the soldiers on the riverbank and asked what they were doing.

‘Don’t you worry, sir,’ the soldier told him. ‘That river’ll not be breaking its banks this year.’

The soldier took a bag of sand from his mate, dropped it on top of all the others and stamped it into place with his boot. Mister Morris looked at all the sandbags piled up along the edge of the river and the lorry-load of sandbags waiting to be piled on top of them and felt that chilly feeling sweep over his shoulders again.

He’d spent the best part of a year working on this project. Every day straight after breakfast he’d sat in his boat, imagining paddling down his own home-made tunnel. He’d even bought some greaseproof paper to wrap around his sandwiches and a flask for his tea. But now all the life seemed to suddenly drain right out of him. And all the effort he’d put into the tunnel seemed to catch him up. For the first time in his life he felt like an old man. A useless, worn-out piece of work.

Mister Morris stopped his digging. He took to his bed and listened to his radio. And all the time his mind was piled high with those blasted sandbags which were keeping the river at bay.

The following week the rain came, just as Mister Morris predicted. It lashed the windows and drummed on the roof of his unhappy house. He put on a raincoat and found his umbrella and went down to the river to see how high it was getting. The water swept by at quite a lick and came right up to the sandbags. If those soldiers hadn’t put them there, Mister Morris thought, he’d be in his boat, paddling up and down that tunnel he’d spent all year hacking out of the ground.

It was starting to get dark. He looked at the sodden sandbags by his feet. Here and there the odd trickle of water seeped between them. Now, if only one or two sandbags happened to get knocked out of the way, Mister Morris thought to himself.

He gave one of them a little kick with his wooden leg, but couldn’t get enough power behind it. He took his umbrella down and tried prodding at the sandbag with that instead. In truth, he wasn’t making much of an impression when he had a funny feeling that he was being watched. He turned and found a man standing not far away, wrapped up in a raincoat. After a couple of moments the man took a step towards Mister Morris.

‘Do you need a hand?’ he said.

As he came a little closer, Mister Morris could see that the man was about the same age as himself, if not a little older. The fellow bent down, picked up one of the sandbags and handed it back to Mister Morris. Mister Morris took it and turned to throw it over his shoulder when another man, of similar vintage, suddenly appeared.

‘I’ll take that,’ he said.

Within a minute there were a dozen of them, all working together. Twelve old men handing the sandbags down a chain, just like the soldiers who’d brought them in a few weeks before.

The first sign that their endeavours had been successful was when the man next to Mister Morris called out, ‘That should do it,’ and waved for everyone to get out of the way. A couple of sandbags slowly rolled aside under the weight of the water. Then the river seemed to suddenly sense a new course for itself, punched a hole right through the bank of sandbags and sent them tumbling all over the place.

Mister Morris hurried home just as fast as his leg would carry him. By the time he opened his cellar door there was at least two feet of water flushing straight down his tunnel and his boat was tugging at its leash.

He grabbed his torch and climbed into his row-boat, which was so eager to be on its way that Mister Morris found it impossible to untie the rope and had to cut it with a knife. Then he was off, racing down the rapids, down his dark, dark tunnel, with hardly time to catch his breath.

Mister Morris didn’t get the chance to do much rowing. He was too busy trying to keep his boat from being smashed to smithereens. The walls flew by and when he wasn’t guiding the boat between them he was shining his torch over his shoulder, to see how far he had to go.

It was quite a ride and one that Mister Morris wouldn’t have missed for the world. It was the sort of exhilaration he rarely experienced behind the counter at the hardware shop. But just when he’d begun to thoroughly enjoy himself and to whoop and hear his own whoops echoing back at him, the boat began to slow and he found himself at the end of the tunnel where the water was boiling and raging from all the other water backed-up behind.

Mister Morris got hold of his oars and started rowing back towards his cellar. He rowed like mad but wasn’t going anywhere. He was held in the grip of the floodwater, as it thrashed and buffeted his boat up against the tunnel wall.

Then he noticed that the water was still rising. For some reason he’d imagined that it would climb to a depth of a couple of feet, then simply stop. But the boat was being steadily lifted on the water, with Mister Morris inside, furiously rowing, until at last he found himself being pressed right up against the tunnel roof.

The water kept on coming and began to creep over the side of the boat. The torch went out, the water roared and churned around him and in that terrible watery darkness Mister Morris finally surrendered to his fate.

‘It’s not such a bad way to go,’ he thought to himself. ‘Drowning in my own tunnel, in my own home-made rowing boat.’

The water completely engulfed him. Mister Morris slumped forward.

‘This is it,’ he said out loud.

But at that last moment, when his whole life seemed to swim about him, the stubborn wall gave way and Mister Morris, his boat and the millions of gallons of water behind them were launched into what felt like the very heart of the earth.

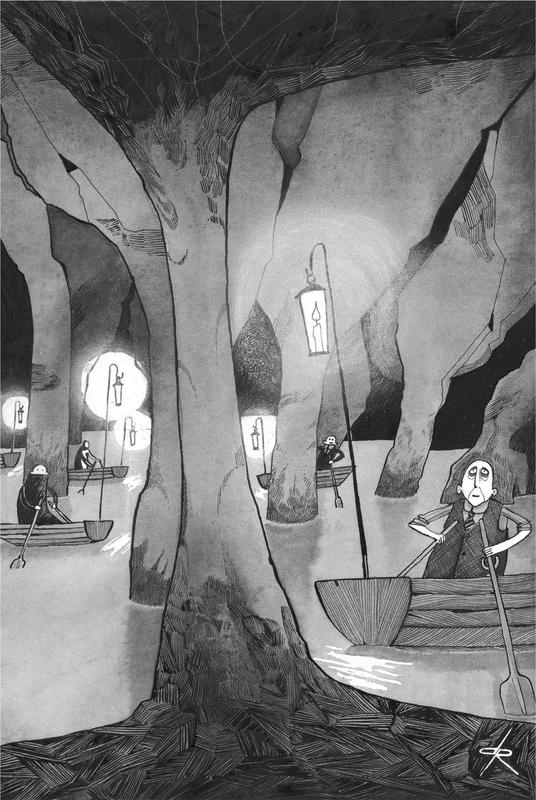

When things eventually settled down and Mister Morris dared to sit up straight he found himself in unfamiliar surroundings. His boat was gently drifting in the middle of a vast underground lagoon. Vast stalagmites and stalactites reached up and down around the water’s edges. And all the walls and the cavernous ceiling had a smooth and eerie sheen to them.

Mister Morris noticed several other boats drifting here and there in the distance. Each had a hurricane lamp hanging from a pole. One of the boats was slowly being paddled over towards him. When it finally came alongside, Mister Morris recognized the owner. It was the old fellow from the riverbank.

‘Glad you could join us,’ he told Mister Morris.

Mister Morris did his best to regain a little composure. ‘That’s very kind of you,’ he said at last.

‘You’ll be needing a lantern,’ the other fellow told him. ‘To see where you’re going.’

Mister Morris nodded. ‘I know a shop where I can pick one up,’ he said.

The other fellow smiled and started to turn his boat around.

‘We tend to leave each other alone,’ he said. ‘But if you want a bit of company, just give me a wave.’

Mister Morris thanked him, then watched as the old fellow rowed off into a quiet stretch of that vast, milky lake.

‘I should’ve brought some sandwiches,’ Mister Morris thought to himself.

For the rest of his days, Mister Morris rowed on the lake on a regular basis. It gave him the chance for a little reflection. He also liked to think that the rowing kept him fit. And as he rowed he remembered his mother and father and the day they rowed on Lake Windermere. And, from time to time, he thought about his old friend Frank, who died in the war all those years ago.