A coincidence is sometimes just the world’s way of getting your attention – a way of getting you to sit up and take notice once in a while. Some coincidences are so slight as to barely merit a raised eyebrow. Others carry such weight that, when acted upon accordingly, they have the power to change the course of your life.

The coincidence at the heart of this particular story is of quite considerable magnitude, not least for the boy and the butterflies involved. It has its origins one Saturday morning when Baxter Campbell paid a visit to the Houghton Museum – a place packed full of stuffed bears and birds and Paraguayan nose-flutes and various bits of bone and stone which had, at one time or another, been brought back from every corner of the world.

Baxter was himself an unusually cultured young fellow. In his bedroom he kept an old harmonium on which he would compose his own maudlin lullabies. On his bedside table sat a leather-bound collection of the poetry of Alfred Lord Tennyson. On his walls were pinned the paintings of Pieter Breughel and Hieronymus Bosch. All of the above he’d picked up for next to nothing in jumble sales and junk shops. Like his dad, Baxter found anything old or second-hand peculiarly alluring. Old stuff had history to it. Old stuff had character.

When Baxter was still a baby he accompanied his father to every second-hand shop, street market and auction on his busy itinerary. So, long before he could walk or talk, Baxter was already familiar with the smell of mould and mothballs and the sight of grown men haggling over the sort of old books and clocks and china most people would just throw away.

These days, Baxter was old enough to go on his own to the same second-hand shops and flea markets his dad had introduced him to. And on Friday nights he and his dad liked nothing better than to sit by the fire and trawl through the small ads in the back of the local paper, circling any item they liked the sound of, such as ‘Cast iron bedstead. A bit bent. Very heavy’ or ‘Large box of chemistry equipment – eg test tubes, pipettes, etc. Offers please.’

If there’d been a Mrs Campbell she might have had something to say about the cardboard boxes which lined the hallway and the stacks of books which clogged the stairs. But Baxter’s mother had departed this world the same hour Baxter had entered it. Baxter’s father had raised him on his own and early on the two of them had come to an agreement whereby Baxter’s dad would store all his stopped clocks, Second World War memorabilia and railway paraphernalia in the basement and Baxter would have the use of the attic for his old adding machines and broken wirelesses.

On Saturday mornings Baxter liked to visit one of the local museums and have a look at some ancient pair of Roman underpants or the shin bone of some Neolithic Man. He liked to eat his lunch at the Turkish café and, in the afternoons, to call in at all the jumble sales he’d picked out of the paper the night before. On this particular Saturday Baxter stood in the Houghton Museum before a glass cabinet containing an old pair of handcuffs. They came from Bristol, apparently, and looked as if they weighed a ton. Baxter wondered what sort of crime you had to commit to find yourself wearing them and whether the same poor sod who’d been shackled by them had been whipped within an inch of his life by the cat-o’-nine-tails from the neighbouring cabinet.

Baxter walked on, past the polar bear, baring its teeth and raised up on its hind legs, past the row of Balinese slippers and the display of Moroccan board games and only paused when he came face to face with a poster which announced ‘BUTTERFLY: a new exhibit by Milton Spufford’ with a big black arrow pointing into the next room. As we have already established, Baxter Campbell was a cultivated boy and not the least bit intimidated by either Art or Culture. And as he still had plenty of time before his next appointment (a jumble sale up at the Methodist Church at one o’clock) he decided to follow the signs, passed through an archway and came out into a large white room.

What struck him first were the incredible colours – the colours and the actual size of the thing. Vivid blues, emerald greens and luminous turquoises all shimmered together in the two huge wings of a single vast butterfly which was so big it practically filled the whole of one wall.

Baxter was impressed, there was no denying it. The creature somehow managed to be both beautiful and monstrous at the same time. It was only as he walked towards it that he saw how that massive butterfly was actually made up of several hundred real butterflies which had been carefully arranged into something like a huge mosaic.

‘Oi!’ someone said.

Baxter jumped. Without realizing it, he’d walked right up to the butterfly and raised his index finger. An overweight security guard, standing about ten feet away, seemed quite prepared to bundle Baxter to the ground if necessary.

‘No touching,’ he said.

Baxter brought his hand down and went back to studying the individual butterflies. He could see the fine fur which covered their tiny bodies – the faint veins which wired their wings. One butterfly’s wings were all chalky blues and whites, as dusty as powder paint. Another’s were so black and glistened so wetly they looked as if they had just been dipped in ink.

Each was so pristine that Baxter was having trouble believing they weren’t still living - as if they might have been specially trained to hang in formation all day long. It was a nice idea but one which promptly vanished when Baxter noticed the head of a pin in the middle of the butterfly right in front of him, then of every other butterfly, which held them to the wall.

Baxter was beginning to feel quite ill. He decided to leave the museum. On his way he passed a large photograph of Milton Spufford, the man who’d put together this weird work of art. He was standing on a hillside in baggy shorts, with a butterfly net in one hand and a large glass jar in the other. Underneath the photograph it said: ‘Once caught, the butterfly is dropped into the “killing jar” where the smell of crushed laurel leaves soon lulls the creature into a permanent sleep.’

Baxter was completely bamboozled. He’d come across plenty of dead animals in his time – tatty fruit bats … over-stuffed walruses … rhinos with paper-thin skin – but they’d all been caught and stuffed at least a hundred years earlier. The idea of someone catching and killing butterflies these days just seemed plain stupid. You’d have thought there were few enough butterflies to begin with, without going round sticking pins in them.

He left the museum and did his best to forget about those beautiful dead butterflies, but wasn’t particularly successful. And for the rest of the afternoon as he rummaged at his various jumble sales that monstrous butterfly kept looming up in his imagination and threatened to overshadow the whole weekend.

A couple of weeks later Baxter paid his monthly visit to Monty Eldridge’s Second-Hand Emporium. Monty liked to think of his establishment as more of an antique shop than a junk shop and his prices tended to bear this out, but Baxter knew that he was far more likely to turn up something interesting at Monty’s place than most of the others, even if he was less likely to be able to afford what he found.

Baxter was right at the back of some dimly lit room, trying to squeeze between a fancy lamp-stand and a table piled high with crockery, and Monty was over by the counter reading his paper when Baxter noticed an old mahogany box, about the same size as a small medicine cabinet. He eased it out from under an encyclopedia. The box was surprisingly heavy, which gave Baxter hope that it might contain something particularly old or unusual. He set it down on a rickety old table, pushed back its little latches and carefully opened the lid.

A powerful smell of mildew came up from the plush interior as Baxter caught his first glimpse of a gleaming set of silver instruments – tiny knives, needles and pairs of pincers – all laid out on a bed of velvet and each in their own custom-made cavity. Two corked phials were strapped into the box’s lid, along with some sort of eyepiece and a well-thumbed manual. It looked like a set of tools which might have belonged to a dentist or a watchmaker.

‘What’s this?’ Baxter called out to Monty.

Monty looked up, put down his newspaper and strolled over to see what Baxter had found.

‘Ah now, those’, he announced with some relish, ‘are a lepidoctor’s surgical implements.’ He picked out a particularly deadly looking blade and studied it. ‘Late Victorian. Very rare. I’ve not had a set of that sort of quality for nigh on thirty years.’

Baxter picked out a pair of tweezers. They were beautifully constructed but finely fringed with rust. ‘A lepiwhat?’ he said.

‘A lepidoctor,’ Monty told him. ‘Bit of a lost art these days. And probably something of a secret society way back then.’

Baxter replaced the rusty tweezers and brushed his fingers over the other instruments. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘but what are they for?’

Monty shook his head, as if despairing at the depths to which educational standards had fallen. ‘A lepidoctor’, he said, ‘was someone who specialized in carrying out repairs to butterflies.’

If you had asked Baxter Campbell at that particular moment if he properly appreciated the significance of his discovery and whether he recalled the peculiar exhibition from a fortnight before he may not have been able to tell you. All he knew was that he wanted to own that box of tricks more than he’d ever wanted to own anything. He had fallen in love with its strange array of sinister instruments long before he understood what purpose they served. All the same, Baxter had spent enough time in the company of second-hand dealers to know that it never pays to show your enthusiasm. So he continued to quietly pick over the silver implements. He slipped the magnifying glass out of its leather strap – the sort of eyepiece jewellers use to examine diamonds – and blew the dust off it. He put it up to his eye: it was a perfect fit.

‘So, what’s it worth?’ he said, as he leant forward and examined the other tools through it.

‘Well, that depends’, said Monty Eldridge slyly, ‘on what someone’s willing to pay.’

It took quite a while to get old Monty to say how much he wanted for the lepidoctor’s instruments and, almost inevitably, it was far more money than Baxter could hope to find. But Monty happened to remember an old gramophone Baxter had bought off him a year or two earlier (whilst explicitly failing to mention the fellow who’d been offering good money to get his hands on one) and it took another five minutes’ hard bargaining before a deal was struck, in which Baxter agreed to trade in his old gramophone and fix the gears and brakes on Monty’s bicycle in return for that box of surgical tools.

When Baxter finally took the mahogany box home a few days later he whisked it straight up to his room and closed the door behind him. This was, in itself, highly unusual. His father was normally the first person to whom he’d show some new, peculiar find. He placed the box on his bed and knelt down beside it. He opened it up and took out each silver tool in turn. He examined them all through the dusty eyepiece. None appeared to be broken, although he thought the spring on a pair of pincers would probably benefit from being replaced. The two glass jars were empty, or, at least, what little remained in them had set solid, like old varnish. Baxter pulled out the booklet and had a quick flick through it. The binding was split and the pages were worn and grubby, as if the previous owner must have thumbed through it a thousand times.

He turned to the first page and started reading. In the third paragraph he read:

There is no reason to suppose that any moth or butterfly should be entirely beyond resuscitation, no matter how many weeks or months they have lain inert, as long as the internal organs are present and correct or may be easily rectified and the wings, antennae, etc. are not too badly decayed.

Baxter felt his heartbeat quicken – could feel it pumping in his ears. If there had been any lingering doubts as to what he must do, they promptly evaporated. In anyone’s life there are few enough occasions when one is absolutely certain of something: when the facts stand right before you like some solid, unmovable truth. But Baxter knew, as he sat there with the room slowly darkening about him, that this was one such occasion and that his course of action was laid out for him.

Over the next couple of days he worked through the worn-out manual from cover to cover, then went back to the start and read through it again. Some of the words were distinctly old-fashioned and he had to look up quite a few in the huge old dictionary he’d picked up in a charity shop six months before. Fortunately, the manual contained its own short glossary, where most of the technical phrases of butterfly repair were explained and by the time he’d read right through it a third, then a fourth time Baxter found that the instructions had begun to make their own strange sense.

The book described six quite complicated procedures which, the reader was assured, would take care of the vast majority of butterfly injuries. Baxter was fairly mechanically minded, which is to say that he had repaired several dozen bicycles and replaced valves and soldered loose connections in as many wirelesses. But he couldn’t help but feel that tinkering with the wings or the insides of such a delicate creature was an altogether different proposition to replacing a spring on a radio dial.

He cleaned all the tools with wire wool and methylated spirits and, by following the diagrams, acted out the intricate operations on imaginary butterflies, to the point where he just about managed to convince himself that he might have a hope of pulling it off. The problem was that at least half the operations contained the instruction ‘Apply sealing gum’ and every procedure concluded with the instruction to ‘administer revivifying fluid’. Applying the sealing gum seemed remarkably similar to applying glue to paper. Administering revivifying fluid seemed to consist of nothing more than pulling the cork from one of the bottles quite close to the butterfly, and watching it spring back into life. However, the jars which had once contained the ‘sealing gum’ and ‘revivifying fluid’ were both practically empty. If any butterflies were to be revived Baxter would have to get his hands on the necessary gums and fluids. Until this had been done there was no point even contemplating how to get the butterflies out of the museum and up into his room.

‘Lepidoctors’ didn’t feature at all in the local telephone directory and there was no sign of them in his big old dictionary. Baxter concluded that either the word was so incredibly old that it had fallen out of circulation or was so shrouded in secrecy that even the most formidable-looking books didn’t dare whisper its name.

He had just about given up hope of ever finding the appropriate glues and fluids when he made a timely discovery. He was tugging at the leather strap which held the bottles in the lid when the silken upholstery came away in his hand. There, beneath it, on the bare wood was a printed label, which read ‘Lepidoctors’ supplies c/o Watkins and Donalds, 119, Hartley Road, London W11.’

Baxter knew he had an old London street map somewhere but, like a lot of things, it took a while to find it. He finally tracked it down up in the attic in a stack of 1950s wrestling magazines. Baxter opened out the map on his bedroom floor and in a matter of minutes managed to establish that Hartley Road was somewhere between Westbourne Grove and Portobello Road. So, on the following Saturday, instead of doing his usual round of museums, second-hand shops and jumble sales, he took the train to London’s Paddington Station and, with his old map of London flapping about before him, followed the maze of streets to what he hoped would be the main supplier to the country’s remaining lepidoctors.

Hartley Road itself was decidedly ordinary, with a terrace of houses down one side and a couple of blocks of flats on the other. Right from the start it didn’t quite feel like the kind of place where a boy might get his hands on butterfly remedies. As he walked along, Baxter kept an eye on the house numbers and soon noticed a row of four or five shops up ahead. When he finally stood before them his heart sank. There was a pub, a newsagent, a launderette and a chemist. The same row of shops you’d expect to find in any town. There were no shadowy doorways, as Baxter had hoped for – no intercoms into which he could conduct some whispered conversation. Nothing secretive or sinister at all.

Number 119 was the chemist’s shop. The numbers were stencilled in gold on to the glass above the doorway. The shop window was filled with a display of boxes of hair dye. On each packet a middle-aged man with dark brown or jet-black hair smiled out at the world. This in itself was a bit of an eye-opener. Baxter was vaguely aware that some women dyed their hair, but had no idea that men were at it. It was news, but not exactly big news. Yet, Baxter had a sneaking suspicion that this might be about as exciting a revelation as he was likely to have that day.

All the same, he was not about to go home without at least making a cursory enquiry, so he pushed the door, which set a small bell ringing above it, and by the time he got to the counter an Indian man in his fifties or sixties had emerged from behind a curtain and was there to meet him. He was a kind-looking fellow – quite thin, with a head full of wavy, grey hair. It occurred to Baxter that, with so many boxes of men’s hair dye in his shop window, the proprietor might have considered dyeing his own hair. The only reason Baxter could come up with for him not dyeing it was that he might actually like it grey.

‘How can I help you?’ the chemist asked Baxter.

Baxter was finding it hard to concentrate. He kept thinking about grey hair and why someone may or may not want to dye it. He glanced up at the shelves to his left and right, as if he might find a sign for ‘Butterfly Gum’ or ‘Revivifying Fluid’, but there was nothing but toothpaste and aspirin and flu remedies, just like in any regular chemists.

Without quite knowing why, Baxter placed his hands on the counter before him – perhaps to try and stop himself from collapsing in a faint. He leant forward, which encouraged the chemist to do the same.

‘I need some supplies,’ Baxter whispered.

The chemist didn’t move a muscle. ‘And what sort of supplies exactly are we talking about?’ he whispered in reply.

Baxter leant even further forward, so that his mouth was right up to the ear of the chemist, which was tucked away among all that wavy, grey hair.

‘A lepidoctor’s supplies,’ said Baxter.

The chemist stood up straight and stared back down at Baxter as if he was completely bonkers. Baxter searched the chemist’s face for some hint of comprehension, but found nothing. In fact, the fellow looked as if he was considering calling the police. Baxter was ready to give up, but thought that as he had come all this way and had made such a fool of himself already he had nothing to lose but the last few shreds of his dignity. He reached into his jacket pockets and pulled out the two empty phials from his lepidoctor’s kit. He held them up, where there could be no mistaking them. The chemist stared at one jar, then the other. He glanced at the door over Baxter’s shoulder, pulled back the curtain and nodded his head towards it.

‘In here,’ he said.

The room was not much bigger than a pantry. The shelves on all four walls were packed with great tubs of pills and boxes of sticking plasters. Without saying a word the chemist headed over to an old wooden cupboard. He took a tiny key from his jacket pocket, unlocked it and opened the doors to reveal a whole, lost world of lotions and potions and ancient remedies. Half the jars seemed to contain bits of bark or dried herbs. The rest were filled with exotic-coloured oils. The chemist took Baxter’s phials from him, looked them over and set them down on a wooden worktop.

‘How much do you need?’ the chemist asked him.

Baxter hadn’t the faintest idea.

‘Put it this way,’ said the chemist, helpfully. ‘How many butterflies are you hoping to repair?’

Baxter was a little taken aback to be talking so openly on the subject. He tried to picture the huge mosaic on the wall of the museum. He shrugged his shoulders. ‘Maybe a thousand,’ he said.

The chemist raised his eyebrows and let out a low whistle, apparently quite impressed with Baxter’s plans. Then he turned back to his cupboard and lifted down a large jar of something syrupy and placed it on the counter. He unscrewed the lid and began to ladle the contents into a smaller bottle – about the size as a jam jar.

‘If you don’t mind me asking,’ said the chemist as he continued ladling, ‘where did you happen to come across the implements?’

‘A junk shop,’ Baxter told him and imagined Monty’s horror at such a description.

‘That’s quite a find,’ said the chemist and screwed the lid down tight on the jar. ‘Do you know what you’re doing?’

For some reason, the question cut right through Baxter’s defences, and suddenly all his anxieties about repairing the butterflies, which he’d done his best to bury, began to shift and turn inside him. ‘Not entirely, no,’ he said, at last.

‘You’ll be fine,’ the chemist told him. ‘Just stick to the manual. And don’t use too much glue.’

He returned to his old cupboard and took down a large brown bottle, which he seemed to handle with a good deal more care than the previous one. He turned his head away as he prepared to remove the large cork which plugged the top of the bottle, then suddenly stopped.

‘Now, this revivifying fluid,’ he said, and faltered slightly.

‘You know, it’s not exactly cheap.’

Baxter had to admit that he didn’t. ‘What’s it going to cost me?’ he said.

‘The sort of numbers you’ve got in mind …’ said the chemist and did a bit of quick mental arithmetic, ‘you’re talking about a hundred and fifty quid.’

Baxter felt his jaw drop. There was no way in the world he could conjure up that kind of money. He’d just begun to feel a little confidence growing in him. Now all his hopes were dashed again.

The grey-haired chemist could clearly see what Baxter was thinking.

‘If that’s a bit steep,’ he said, ‘there is an alternative.’

Baxter said he’d like to hear it.

‘Menthol,’ the chemist told him.

Baxter was none the wiser.

‘Just suck on a cough sweet for a couple of minutes,’ the chemist explained. ‘Then exhale.’

He pursed his lips and gently breathed out into the palm of his hand.

‘Does it work?’ said Baxter.

The chemist nodded at him. ‘Oh yes,’ he said.

The old man popped his head back through the curtain to make sure that no one was watching, then ushered Baxter back into the shop. He took a handful of packets of cough sweets down from the shelf and packed them into a brown paper bag, along with the jar of adhesive, then totted everything up on his till.

The whole lot came to less than a fiver. Back behind his counter, the old man looked like an ordinary chemist again. Baxter paid, picked up his bag, thanked the chemist and headed for the door. He’d almost reached it when he stopped and turned.

‘Do you mind if I ask you a question?’ he said.

The chemist shook his head. ‘Fire away,’ he said.

Baxter was having trouble putting his thoughts into words. ‘If you’ve … If you’ve never actually done it before,’ he said, ‘how do you know if you’re doing it properly?’

The chemist thought about it for a moment. ‘It’s the same as anything else,’ he said eventually. ‘You just pick it up as you go along.’

*

The actual break-in took less than a week’s preparation. Baxter visited the museum on two separate occasions, discreetly investigating its every nook and cranny, then back in his bedroom, drew up plans of the layout of the building, devised a route through it and compiled a list of exactly which part of the museum he hoped to be in at what particular time.

His biggest concern was how to transport the butterflies. He’d never actually handled one, but it was perfectly clear that if they got knocked about too much between the museum and his bedroom there wouldn’t be much hope of them being brought back to life. His first thought was to use his old cricket bag. Then he began to favour the sheet off his bed with all the butterflies gathered up in the middle. But he finally settled on a canvas rucksack he’d bought at a jumble sale the previous summer. He reckoned it was probably big enough to accommodate all the butterflies and was less likely to attract any unwanted attention out on the street. The small brown envelopes were something of an afterthought. He’d bought a giant box of them from a closing down sale in a stationery shop in January and just had a hunch that they would come in handy one day.

On the Friday he raced home from school in under five minutes, picked up the rucksack he’d packed the night before and left a note for his father saying that he’d gone for a walk out to the rubbish dump and that he’d be back in a couple of hours. He got to the museum half an hour before closing and spent five minutes simply strolling around the place, in order to blend in with the other visitors. Then he slipped into the Gents and, once he’d satisfied himself that all the cubicles were empty, opened the broom cupboard he’d discovered on one of his earlier visits and quietly crept inside.

As far as he could tell the cupboard had been abandoned several years earlier. Baxter had taken pity on it and as he crouched on its floor clutching his rucksack he thought he sensed the cupboard’s appreciation in being used again. At five o’clock, right on cue, someone popped their head into the Gents, called out, ‘Anybody in?’ turned the lights out and departed, leaving the door to slowly close on its spring. Baxter didn’t move for another twenty minutes. He just sat in the dark and went through his itinerary one last time. At some point he ate a bar of chocolate, to keep his strength up. Then he crawled out, like some animal emerging from hibernation, and waited patiently by the wash basins for another twenty minutes, just as he had planned to do.

He picked up his rucksack, put his head out into the museum and listened. He couldn’t hear a thing. Then he tiptoed out into the darkened gallery and began to make his way down one of the aisles. The whole museum felt very different in the half-light. Everything was vague and unfamiliar, as if the glass cabinets might house an entirely different collection of beast and artifact to those on show during the day.

Half-way down the aisle he stopped and pulled out the old miner’s helmet he’d picked up at Monty’s a couple of years earlier and sometimes used to read in bed. It had a torch fixed to the front, just above the peak. He had one final, good long listen. ‘Hello?’ he called out into the dark. Nobody answered. He waited another couple of moments, then turned the torch on his helmet on.

The glass case before him was suddenly illuminated. Inside, a pair of owls sat and stared at him, rather haughtily. Baxter did his best to ignore them and as he went on his way the owls’ shadows slowly shifted, until they settled back into the dark.

Every worn old bone and bit of broken pottery seemed to be aware of his presence and somewhat alarmed that anyone should be creeping around the place after dark. Baxter avoided looking into the cabinet which contained the handcuffs. He didn’t want to consider the consequences of being caught.

When he finally stepped into the large white room the light from the lamp on his helmet suddenly spread and filled the place, as if he was a pot-holer who’d just come out into some underground cavern. The giant butterfly was still there – still pinned in position. Baxter tiptoed over to it. He put his face right up to one of the butterflies. Its fine black wings were laced with blue and gold.

‘Let’s see what we can do for you,’ he said.

It took him a while to work out how to remove the pins without causing even more damage, but found that by sliding the nails of his thumb and middle finger under the head of each pin and giving it a sharp tug, both the pin and the butterfly came quite cleanly away from the wall. Then it was just a moment’s work to take the butterfly off its skewer and slip it into its own little envelope. He studied the first three or four. All were punctured by the tiniest holes. And as he carried on he wondered, not for the first time, if it really would prove to be possible to revive a creature that had effectively been crucified.

After half an hour the sheer effort of concentration was beginning to make Baxter’s head spin. After an hour the tips of his fingers were dreadfully sore. By then he’d managed to prise away and deposit in their individual envelopes at least two-thirds of the butterflies. The rest were out of reach. So Baxter set off to try and find something to stand on.

He walked around the whole museum in his miner’s helmet without finding a single chair or stool. In fact, the only thing which looked as if it might be capable of supporting him was the old polar bear. He dragged it back and pushed its plinth right up against the gallery wall. It was about the right height and when Baxter climbed up on to its shoulders the bear’s raised paws felt as if they were holding on to his shins to stop him falling, which gave him some much-needed confidence.

Half an hour later Baxter slipped the last butterfly into its brown envelope. All that remained were a thousand tiny holes in the wall in the shape of a butterfly, and a thousand pins scattered about the floor. The polar bear leant against the wall, apparently exhausted. When the head of the museum arrived the following morning it would look suspiciously like the polar bear had dragged itself into the snow-white gallery where it had indulged in a midnight feast of butterflies. Whatever had taken place the polar bear had clearly played some part in it, but the bear, like every other animal in the museum, was keeping mum.

Baxter slipped out on to the street and pulled the museum door to behind him. His rucksack was full, but not too heavy. Those precious envelopes made him walk with a great deal of care. He saw himself as some sort of Postman of the Butterflies. He walked with his head up, so as not to look guilty, and everything went smoothly until he was less than a hundred yards from his house and he bumped into Mister Matlock, one of the neighbours, who happened to be out walking his dog.

‘Hello, young Baxter,’ he said. ‘Have you been camping?’

Baxter didn’t much like Mister Matlock. He was the sort of person who was always smiling but never seemed to be thinking particularly nice thoughts.

‘It’s a new rucksack,’ Baxter said. ‘So I thought I’d give it a try-out. You know, just a couple of times round the block.’

Mister Matlock smiled but his eyes were as dead as a dodo’s. It was always his eyes that gave him away – as if he was thinking that if he had his way, Baxter’s house would be bulldozed and he and his dad thrown out of town.

Baxter said goodnight, pressed on and as soon as he was in the house, crept up to his room and locked the door. He undid the rucksack’s drawstring, gently upended it and watched as a thousand envelopes spilled on to the bed. Baxter thought it was probably about as close to flying the butterflies had got since that terrible moment when they found themselves in Milton Spufford’s killing jar. It was now up to him to see if he could get them flying again.

He pulled out his box of tools from under the bed and set it down on his old desk. He adjusted the height of his stool, turned the lamp on, reached over to his bed and picked an envelope off the top of the pile. He put the magnifying glass up to his eye and held it there like a monocle. Then he set to work.

There was a tiny hole where the pin had been inserted and on the other side of the butterfly, where the pin had surfaced, a minuscule tear. This allowed Baxter to peel back the skin with his tweezers and to have a look inside without making any extra incisions. As far as he could tell, most of the muscle and tissue was intact and, according to the manual, all that was necessary was to carefully knit the flesh back together, apply a drop of gum and revivify.

That first butterfly was a stunning combination of black and amber, with unusually frilly wings. Baxter carefully repaired it, glued it and let it dry for several minutes before daring to attempt to revive it. Then, when he felt quite sure that the adhesive had set, he unwrapped his first cough sweet and slipped it into his mouth. He sucked away until he could taste all the medicinal flavours seep into his tongue and felt his nose begin to tingle. He placed the butterfly in the palm of his hand, just like the chemist had shown him. He rubbed the cough sweet up against the roof of his mouth a couple of times and with the butterfly no more than six inches from him, gently breathed his warm, mentholy breath over it.

For a moment or two nothing happened. The butterfly just sat there, as mute and motionless as it had been on the museum wall. Baxter felt a great wave of disappointment rise up in him and he was about to give the butterfly a second dose when its wings suddenly twitched. It flexed its tiny antennae and moved its six little legs. And the whole elegant creature began to slowly stretch and shift in Baxter’s hand.

Baxter laughed out loud as he stared at what had been, until a few minutes earlier, a beautiful but lifeless thing. And yet he was simply witnessing what he’d endlessly dreamt of – of breathing life back into a butterfly. Within ten minutes he had successfully repaired another half-dozen, which were all happily fluttering about his room. Baxter was overjoyed but soon realized that this arrangement was far from practical, so he caught each one in his cupped hands, climbed the steps in the corner up to the attic and from then on, as soon as each one showed the first signs of life he would gather it up and release it through the trapdoor into the attic where it joined all the other revitalized butterflies.

He worked right through the night, with that magnifying glass up to his eye as he delicately nipped and sealed and knitted. Now and then an envelope would contain a butterfly with more serious internal damage and Baxter would have to consult his manual and employ some of the more unusual surgical tools. But by the morning he had revived what he estimated to be about three hundred butterflies and decided he had better go downstairs for some breakfast, if only to revive himself.

Half an hour later he was back at his operating table. By mid-morning he had sucked his way through all five packets of cough sweets and had to slip out to the newsagents and buy another dozen or so. The woman behind the counter told him, ‘If your cough’s that bad you should maybe see a doctor.’ But Baxter said he just liked the taste of them, which, by this stage, wasn’t entirely true.

For the rest of the day he worked almost without stopping. Every couple of hours he would have a little walk around the room, just to stretch his arms and legs. Each time he did so he noticed how the pile of envelopes on his bedspread had grown a little smaller. And every time he looked out of his window he saw how the sun had moved a little further through the sky.

The biggest upset occurred after he’d fixed the wings on a particularly large specimen, which were a luminous turquoise, like a peacock’s. He blew some menthol over it, but the moment it sputtered back into being it became clear that one of its wings was still not quite right. Baxter had to carry out further repairs with it flapping and twitching between his fingers. Once he’d managed to complete all his sewing and gluing, the creature seemed perfectly happy but it was a most unpleasant experience and Baxter vowed that from that point forward he would refrain from reviving a butterfly until he was absolutely certain that all the work was done.

At about six or seven on the Saturday evening he went down for his dinner, but was so excited by how few envelopes remained unopened that he was determined to get back to them as soon as possible. In those last few hours he began to have problems with his eyesight. His vision became quite blurred and he could feel a terrible headache coming on. And by the time he had repaired and revived the last one and released it into the attic it was long past midnight. He felt as if he’d run a marathon. He lay on his bed and calculated that he must have sucked his way through at least two hundred cough sweets. He wondered if he would ever get the taste of them out of his mouth. He closed his eyes. He just needed to close them for a second. And within a minute he was fast asleep.

He awoke with a jolt about four hours later. The sun was rising. He looked at his watch. Almost six o’clock. He sat himself up and when he was sure that he was awake and had got his thoughts in order he went over to the corner of the bedroom and quietly climbed the wooden steps.

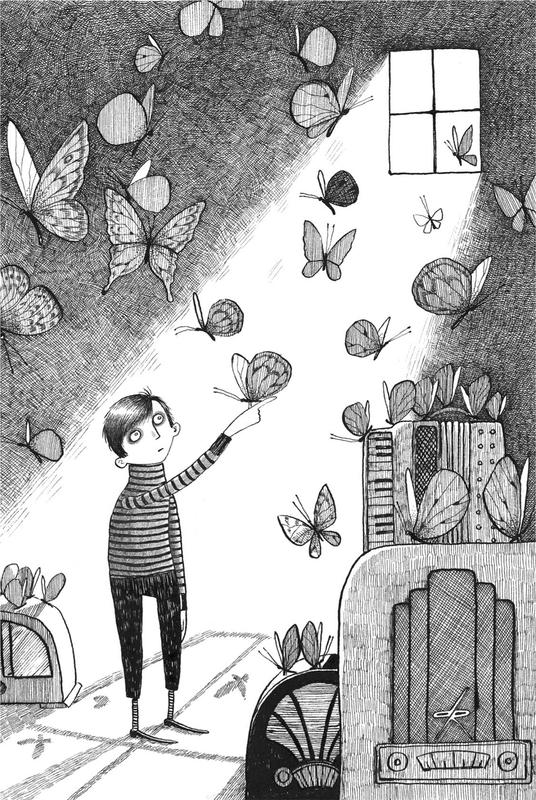

He opened the trapdoor, very gently, expecting to find the attic full of frantic life, but the room was perfectly still. He climbed the last few steps and closed the trapdoor behind him. And as he stood there he was suddenly gripped by the fear that all his butterflies had flown away before he’d had the chance to see them together, or had slipped back into their slumber after only a few snatched hours of life. But as his eyes slowly grew accustomed to the darkness, he began to see them – a coat of butterflies covering all his old tape recorders and broken radios, their wings slowly winding backwards and forwards, as if they’d been waiting for him.

He carefully made his way over to the skylight and pushed it open. Then he slowly crept back to the far side of the room. For a minute the attic was still again. There was just the sound of the town slowly waking far below him and Baxter up in his attic among his butterflies. The sun continued to rise above the rooftops and a gentle breeze swept in through the skylight. The butterflies began to stir. The first few took to the air and fluttered about the rafters. The others gradually joined them on the wing. And soon the air was full of butterflies – every colour and every design – until one or two danced out of the skylight, the others followed and in an instant all that delicate life swept out of the room.

Baxter went over to the open skylight and watched them leaving: a great cloud of butterflies rolling over the town. They seemed to know where they were going. They seemed to know what they had to do.

*

Later that same day Milton Spufford, artist and butterfly collector, was standing up on the Downs, with the Weald to the north and the sea to the south and nothing but open hillside all around him, when he spotted an interesting-looking butterfly about ten feet away.

It was his first find of the day. In his right hand he held his butterfly net by the handle. In his left he gripped his killing jar. His eyes never left his prey as he crept over towards it. Its wings were pale green, like two young leaves, and Milton was already imagining what it would look like with all the life drawn out of it and pinned to a museum wall. He got within striking distance and for a moment watched the creature feeding. He raised his net – the same net that had already imprisoned a thousand other butterflies.

‘You’re coming home with me,’ he whispered.

He was about to bring his net down when a dark shadow swept silently over him. The temperature suddenly dropped. The sun was gone and Milton turned to find the silhouette of a massive butterfly hovering above him. The same one he’d so meticulously constructed from a thousand stifled butterflies.

He dropped the net. His killing jar went rolling down the hillside. The giant butterfly slowly flapped its wings. And as he stood there, gaping at his own strange creation, the huge butterfly fell upon him and wrapped itself around him, until Milton Spufford all but disappeared.

He mustn’t have struggled for much more than a minute. With his last breath he tried to call out, but his words were muffled by the butterflies as they gently smothered him. For those last few moments he was full of colour. He was alive among his butterflies. Until the butterfly collector was finally extinguished and his lifeless body fell to the ground.

He lay on the grass, as if he was deeply sleeping. And when an old lady came across him not long after, she found nothing remotely suspicious in the circumstances. It was a beautiful day, she told the inquest, with the sun high in the sky, a gentle wind blowing and hundreds of butterflies dancing everywhere.