Sitting at a desk all day can be very demanding. Pretending to look as if you’re paying attention can be an almost impossible strain. The children of 4B were hot and tired and beginning to grow restless. And there were still twenty minutes to go before the bell was due to ring.

Theodore Gutch was watching the clock on the wall behind Mister Morgan – was watching the second hand slowly sweep around the clock’s circumference until it finally found its way back up to the twelve.

‘Twenty more of those,’ thought Theodore, ‘and I’ll be a free man. Free to do whatever I please.’

Theodore looked around the room for something else to occupy him. He considered trying to hold his breath whilst counting the drawing pins on all four walls – a little trick he’d very nearly pulled off a couple of days earlier and may well have had another crack at it, had he not been distracted by a flash of light through the window to his left. Now, there is every chance that the flash of light was caused by someone on the other side of town opening a window. As that distant window shifted on its hinges it could have momentarily caught the sun. To be fair, even Theodore Gutch knew this to be the most likely explanation. But the previous week he’d read a book about an army of Martians landing in a small town in America and wreaking all sorts of havoc. And with nothing better to do with the remaining minutes of this particular Wednesday, it wasn’t long before it occurred to him that the flash of light could just as easily have been the after-burners of some alien spacecraft as it landed in the playground in Lowerfold Park.

The threat of an alien invasion was certainly a lot more interesting than whatever Mister Morgan had to offer. Sometimes even Mister Morgan didn’t seem especially interested in what he had to say. Theodore glanced around the room. Across the aisle, Robert Pinner was staring at the palm of his right hand, trying to work out from the lines which crossed it how long a life he had left to live.

Theodore plucked a piece of paper from one of his notebooks, picked up a pencil and scrawled a few words on it. ‘A spaceship full of marshuns’, he wrote (Theodore was not the best of spellers), ‘has just landed in Lowerfold Park.’

Robert Pinner’s ruminations were rudely interrupted when a paper plane landed on the desk right in front of him. It made him jump and he looked round to find Theodore Gutch staring back at him, as if his eyes were about to pop right out of his head.

Theodore nodded at the plane. ‘Open it up,’ he hissed.

Robert ducked his head down behind the boy sitting in front of him (a boy named Howie Barker who had plenty of body to hide behind) and carefully unfolded the piece of paper. He read the message, frowned and looked back at Theodore, who was now nodding his head most gravely.

‘It’s true,’ he said, and did so with such conviction that Mister Morgan was obliged to stop in mid-sentence and ask Theodore if he might possibly refrain from talking when he was talking, as it rather interfered with his train of thought.

It doesn’t take long for a rumour to do the rounds – especially a rumour concerning alien invasion – and there are few situations better suited to a rumour spreading than a room full of children who are bored to tears. Every time Mister Morgan turned his back there was a great flurry of activity, as Theodore’s note and several new ones were frantically passed from desk to desk. One of the new notes stated, quite categorically, that ‘250 aliens’ had landed. On another, Colin Benson had drawn the actual spaceship – a pointy rocket resting on two wide fins. Beside it he had attempted to draw his own idea of an actual alien, but couldn’t get its head and arms quite right and in a fit of frustration had scribbled it out, which left the impression of a ghostly figure staring out through the interference on a TV screen.

With five minutes still to go before the bell, 4B was in a state of near-hysteria. Mandy Shaw thought she was going to wet herself with excitement. Barry Marsden gripped the edge of his desk so tightly that his knuckles had turned quite white. One or two children had taken the news quite badly. Others thought it was the most exciting thing to happen since the crisp factory went up in flames. A few pupils privately wondered whether the report was one hundred per cent accurate. But all were united in their determination to be on their feet as soon as the bell started ringing, to race round to the park and have a good look at this alien spacecraft for themselves.

Those last few minutes were fraught with tension. Mister Morgan could tell that there was something brewing: the whole classroom seemed to crackle with anticipation and everyone kept glancing over at the windows, as if they might catch sight of something unusual there.

‘Perhaps there’s going to be a fight,’ thought Mister Morgan. Mister Morgan quite enjoyed a little fight. He liked striding in and taking charge of the situation. ‘Break it up, break it up,’ he’d say, as he dragged the two boys off each other. But there hadn’t been a fight in the school playground for over a year and there was no point him asking the children what was going on. They never told him anything.

The moment the bell started ringing the children were out of their chairs and flying down the corridor. Every girl and boy they encountered was told all about the Martian invasion and every one of them instantly chose to join their ranks, until a great stampede of youth was rumbling down the steps and out into the daylight, carrying with it anyone not quick enough to get out of the way.

They piled into the park. They went roaring past the bowling green. They went hammering down the path between the empty tennis courts. They charged through the rose garden, all the way round the duck pond and under the rows of horse chestnuts, fully expecting to find some silver spaceship at the other end. Every child had their own idea of what that spacecraft was going to look like. Some imagined a colossal rocket with steam quietly pouring off it. Some fancied a great silver dish, parked up on the tarmac, with its ramp already down. Some expected to find aliens playing on the swings and round-about, but when they finally arrived at the playground the place was deserted – devoid not just of alien life, but any life at all.

The children slowly came to a standstill. For a while, an eerie silence filled the air. Then disappointment began to set in – the sort of disappointment that can easily turn into anger – until one of the younger children finally opened his mouth.

‘Where’d they go?’ he said.

The silence settled back over the crowd. Then another, older boy shouted, ‘Someone’s taken ’em!’ And, just in case anyone hadn’t understood what he meant the first time round, he added, ‘Someone’s abducted the aliens!’

A disgruntled murmur swept through the hordes of children. The names of various organizations that might conceivably kidnap aliens were bandied about, until a young girl, with no previous history of trouble-making, lifted both hands to her mouth and called out, ‘Let’s all go down to the Town Hall!’

It was a suggestion which was most warmly welcomed. The Town Hall seemed like exactly the right place to take their grievance and everyone had so enjoyed charging through the park like a herd of buffalo that they were keen to go charging off somewhere else.

So they all went roaring down the middle of Church Street. The grown-ups they passed had never seen the like. Cars had to pull up on to the pavement as the children ran cheering and screaming between them, and the owner of the sweet shop on the corner was so distraught at the sight of so many marauding youngsters that he decided to shut up shop and pulled down all the blinds.

Within five minutes the children arrived at the steps of the Town Hall and their defiant roar slowly subsided as it washed up against the hard grey walls of authority. Some of the children feared that their little adventure might now be over. They imagined themselves walking home, defeated and dejected. But the same young girl who’d rallied the troops back at the park brought her hands up to her mouth again.

‘We demand to see the mayor!’ she cried.

In no time at all the whole crowd was chanting, ‘We want the mayor, we want the mayor,’ which was quite exciting for all those doing the shouting and quite intimidating for everyone else.

In actual fact, none of the children had the faintest idea what the mayor actually looked like. The people peering out of the Town Hall’s windows could have sent just about anyone out to try and reason with them and they wouldn’t have known the difference. But the large, middle-aged man who eventually stepped out on to the balcony looked exactly how a mayor was meant to look, with a suit, a vague air of self-importance about him and a great chain of office slung around his shoulders, which he’d been wearing for some fancy reception before being so urgently called away.

Most of the chanting stopped, but here and there small pockets of agitation continued. The mayor stared out at the sea of faces and patted the air, to try and quieten things down. He looked utterly stunned. This wasn’t what he’d had in mind when he signed up for the job three years earlier. Most of his days were spent attending meetings about the bins or traffic lights, or having his photograph taken for the local newspaper at coffee mornings and sponsored walks.

He kept patting the air until some semblance of order had been established. Then, in a clear, strong voice, so that everyone could hear him, he called out, ‘What do you want?’

A skinny boy in a thick pair of glasses shouted, ‘Where are the aliens?’

This was quickly followed by other, similar enquiries, such as ‘Yeah, where are they?’ and ‘What’ve you done with ’em?’

A couple of minutes earlier, when the mayor had been informed that the town’s youth were demanding to see him, his first thought was that they must be upset about the quality of their school dinners or the state of their playing fields. But now that he was out on the balcony and had actually heard their concerns he was quite bewildered.

‘What aliens?’ he said at last.

It was just the kind of remark guaranteed to inflame the situation. Most of the crowd immediately started booing. Some children accused the mayor of being a liar, and went on to make some rather personal remarks about how fat and bald he was. And this commotion continued until one voice managed to make itself heard above all the others.

‘It’s a cover-up!’ he cried.

Those few choice words summed up the children’s mood quite perfectly: their frustration at the mayor’s denial that the aliens even existed, along with their growing suspicion that something deeply sinister was going on behind the scenes. The mayor raised his hands, but it was clear that no amount of patting or shushing was going to bring the crowd to order, so he decided to retreat to the safety of the building and consult some of the many advisers on his staff.

As far as the children were concerned, the facts could not have been plainer: either the aliens had been arrested or the spaceship had taken off again before they’d managed to reach it. Either way, the bigwigs at the Town Hall must have known what had happened and it was, frankly, insulting for them to pretend otherwise. A veil of secrecy had been drawn over the whole alien landing and any communication which had been made with them, but the people at the Town Hall hadn’t banked on a spontaneous uprising of the town’s younger citizens and their demand to be told the truth.

The mayor’s hasty retreat was seen as something of a minor victory and was accompanied by a great deal of cheering and chanting and stamping of feet. Deep in the throng Theodore Gutch was clapping and shouting with the rest of them. Theodore was having the time of his life. He looked around him and thought to himself, ‘I knew it. I knew it was an alien spaceship. We wouldn’t all be here if it hadn’t been.’

By now, everybody was thoroughly enjoying themselves and a giddy, end-of-term atmosphere had taken hold, when it occurred to Sandra Ward, a girl of eight who played the violin and was already up to Grade Four, that she hadn’t seen Miss Bowen, her music teacher, recently. The way in which her thoughts unfolded was probably due in no small part to all the talk of spaceships, along with the fact that Sandra was quite an excitable child. She pictured Miss Bowen walking in the park, and a spaceship hovering high above her. Saw a bright beam of light suddenly pick her out. Miss Bowen shielded her eyes as she looked up. And the next second poor Miss Bowen had been snatched away.

‘Miss Bowen!’ Sandra exclaimed and grabbed the arm of Lucy Gambol, who had a powerful imagination all her own. ‘The aliens have abducted Miss Bowen!’

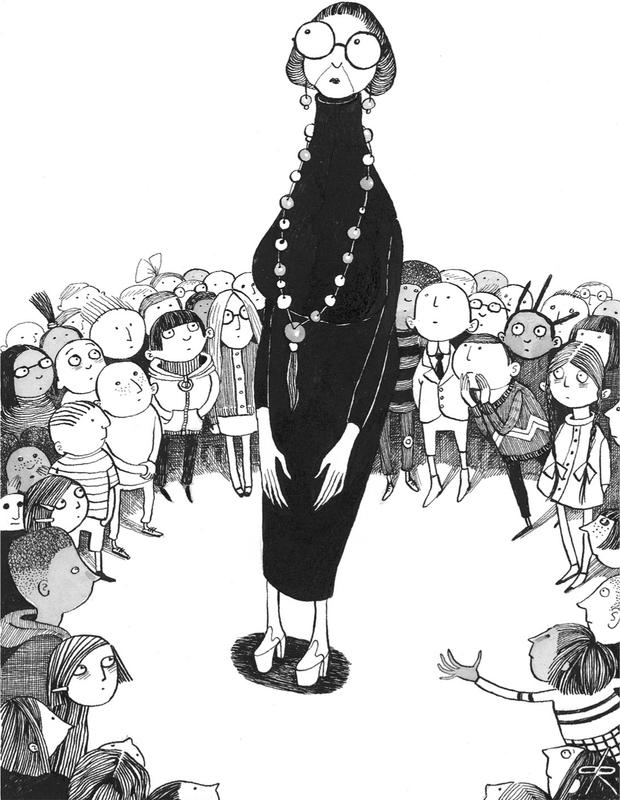

It took a little longer for this rumour to circulate than Theodore Gutch’s, which wasn’t surprising considering the size of the crowd. Miss Bowen was a tall, bespectacled woman in her early forties with an eccentric taste in clothes. She could play the piano, the recorder and just about any other instrument you’d care to put in front of her, including a crumhorn, which looked like a walking stick and, when turned upside down and pumped full of air, made a reedy sort of sound which was very popular with the children, as indeed was Miss Bowen herself. In her music lessons they were encouraged to clap and stamp their feet very much like they’d just been clapping and stamping their feet a minute earlier. Her popularity may also have had something to do with the fact that most of her pupils only saw her once a week.

Miss Bowen was something of a free spirit. Rumour had it that she attended belly-dancing lessons and she once famously burst into tears in front of a class of twenty whilst playing them a recording of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto. So the idea of her being abducted or forced to do anything against her will greatly upset the children, in a way that the abduction of, say, Mister Morgan or Bernie Blakelock, the school janitor, would not have done.

Very soon the chanting had turned into ‘Where’s Miss Bowen?’ and a few minutes later, once they’d managed to get the hang of it, ‘If there ain’t no aliens where is old Miss Bowen?’

Some of the children were beginning to get quite emotional. Who knew who might be abducted next? What Sandra Ward, Lucy Gambol and everyone else had failed to remember was that Miss Bowen only worked on Mondays and Fridays, so whilst they were now convinced she was being held aboard some alien spacecraft she was actually at home, having a bath and reading a book about Sri Lanka – a country she hoped to visit the following year.

Meanwhile, deep in the Town Hall the mayor and his staff were sitting in emergency session around a vast mahogany table as Mrs Haworth, the catering lady, went round with a large pot of strong, sweet tea. One of the mayor’s advisers suggested calling the police, but the mayor wouldn’t have it, knowing that photographs in the local paper of children being handcuffed and bundled into police vans would spell an end to his career.

‘No,’ he said, ‘we’re going to play it softly-softly. We’re going to negotiate.’ And he appointed his youngest, best-looking assistant to talk to the mob in order to try and establish exactly what their demands were and how far they were prepared to go to ensure that they were met.

Five minutes later, Malcolm Bentley stepped warily out on to the balcony and requested that the crowd nominate three children to meet him on the steps in ten minutes’ time.

‘We’re willing to talk,’ he said, and before creeping back to the window, added, ‘We’ve got to find a way through all this,’ which was the first positive thing anyone from the Town Hall had said all afternoon and was met with a polite ripple of applause.

Not long after, the locks on the large oak doors at the front of the building could be heard clanking and turning. One of the doors creaked open five or six inches and Malcolm Bentley slipped out, to be met by the three children who had been chosen as representatives – partly due to their skills in diplomacy and partly because they were bigger than everyone else. The man from the Town Hall shook hands with each one of them. Then he produced a notebook from his jacket pocket and pulled the top off a pen between his teeth.

‘Now then,’ he said, ‘what are your demands?’

‘The first thing’, said Daniel Taylor, ‘is where’s the spacecraft?’

For a moment the young man from the Town Hall stared, baffled, at Daniel. Then he slowly started scribbling ‘Where … is … spacecraft’ on his pad. He nodded his head as he wrote.

‘We’re looking into it,’ he said.

‘Secondly,’ said Janet Barber, ‘is Miss Bowen safe or has she been experimented on?’

‘Miss Bowen,’ said Malcolm Bentley, writing.

Janet told him how to spell it. ‘Our music teacher,’ she said.

Malcolm continued to write. ‘We’ll look into that as well,’ he said.

When he had finished, Malcolm Bentley waited to see if there were any other demands and the three children briefly wondered if they might add one or two of their own. But they had only been sanctioned to present those already given and didn’t want to push their luck, so Daniel Taylor drew the proceedings to a close by saying, ‘That’s it then,’ and nodded his head.

Malcolm Bentley shook hands with all three again, making sure to look each one in the eye, for extra sincerity. ‘We’re going to need a bit of time,’ he said, ‘but I’m sure we can work this out.’

Daniel Taylor was not at all impressed with Malcolm Bentley. He thought he was a creepy piece of work. ‘Well, put it this way,’ said Daniel, ‘we’re either going to be here or we’re going to be at home doing our homework. Where do you think we’d rather be?’

*

A couple of miles away, in one of the town’s grander houses, in one of the better neighbourhoods, the headmistress of the school, Mrs Lambert, was slumped at her kitchen table listening to the radio. She had a mug of tea before her into which she was dunking a succession of ginger biscuits. She had already dunked at least four or five and was telling herself she could dunk just two more and then that would be that or she’d have no room for her baked potato.

She’d once dunked and eaten a whole packet of biscuits in a single sitting – something of which she was neither particularly proud nor especially ashamed. Just as her next biscuit went into her tea the telephone started ringing. She was still busy eating it when she picked up the phone. It was the mayor, who seemed to be doing his best to sound quite calm whilst actually being quite frantic.

He explained how the town square was currently packed with Mrs Lambert’s pupils and how they were becoming increasingly restless. Mrs Lambert found this hard to believe. Her pupils could get a little rowdy from time to time but had rarely shown any inclination to actually go on the rampage.

‘Are you sure they’re my lot?’ she said, which the mayor didn’t find especially helpful.

‘We are,’ he said. ‘They seem to have got it into their heads that an alien spacecraft landed in Lowerfold Park this afternoon and that we’re keeping it from them.’

There was a long pause at Mrs Lambert’s end of the line.

‘That’s not true, is it?’ she said.

‘Of course not,’ said the mayor, before pausing himself.

‘At least, not that I’m aware of. The thing is, they also seem to think that your music teacher has been abducted.’

The pause at the other end was even longer than the last one.

‘Miss Bowen?’ she said.

The mayor confirmed this.

‘Well, why don’t you just tell them that they’re mistaken?’ said Mrs Lambert.

The mayor was beginning to lose his temper. ‘I think we’ve got a bit beyond that,’ he said. ‘They’re all so mad keen on this alien idea that anything we say which they don’t like the sound of is seen as part of some great conspiracy.’

Eventually Mrs Lambert told the mayor she’d see what she could do and promised to call him back in ten minutes. After she put the phone down she stood in the hall for quite a while, just thinking. She was not a woman who was easily flummoxed. She once had five members of staff all phone in sick on the same Monday morning. She had managed to find a way through that little mess and would find a way through this one. She picked up her address book and flicked through the pages until she came to the letter ‘H’ for Mrs Holland, another member of her staff and the woman in charge of the arts and crafts cupboard.

‘Hello, Barbara?’ she said, when the phone was answered. ‘It’s Molly. Listen, we’ve got a bit of a situation.’ She took a deep breath. ‘We’re going to need as much tinfoil and papier mâché as you can conjure up.’

*

Back at the square, the crowd was steadily growing in number as the children on their way home from all the other schools stopped to ask what was going on. They heard about the alien landing, Miss Bowen’s disappearance and the whole Town Hall cover-up and all pledged to stand shoulder to shoulder with the demonstrators and demand the release of poor Miss Bowen … or the aliens … or possibly both.

The children gathered in groups to discuss Important Issues – something they’d never much done in the past. And when their parents finally appeared, wondering where on earth they had got to, and threatened them with dinners gone cold, burnt or fed to the dog, no one moved an inch. Some mothers and fathers tried to drag their child away against their wishes, but the other children linked arms and clung to their trousers and here and there a bit of a scuffle broke out. Tempers frayed, hackles were raised, but in the end the parents relented. To be fair, they didn’t have much choice. They were outnumbered, but could see no immediate danger to their children, and if they were completely honest they might have admitted that what bothered them most was the fact that nothing half as exciting had ever happened to them when they were young.

As the evening wore on, flasks of soup and blankets were handed out to the children. If they were going to be staying out all night, their parents reasoned, there was no sense in them getting cold or going hungry. And as darkness fell the children began to congregate around lanterns and candles and their conversations gradually grew more hushed. The stars came out and they lay on their backs, wondering if their music teacher was somewhere up among them and if she was, whether she was enjoying the experience.

The children slipped deeper under their blankets and their eyes grew heavy, until the only thing to be heard were renditions of ‘Greensleeves’ and ‘Cockles and Mussels’, sung in honour of their missing teacher, complete with all the harmonies she’d taught them the term before.

The night crept by. The children slept and the earth turned on its axis. Now and then, a child would wake and look around at all its sleeping comrades – would blink, smile, then lie back down again. Until, at last, the sky grew pink and the birds gathered on the Town Hall’s window-ledges to warm themselves with the rising sun.

Some of the children were just beginning to stir when the Town Hall door creaked open and Malcolm Bentley slipped out again. He tiptoed over to the sea of bodies, crouched down beside a boy who still wavered somewhere between sleeping and waking and whispered a few words in his ear. Then he moved on, bent down by another child, whispered the same few words, and moved on again, and kept on crouching and whispering before finally creeping back to the Town Hall.

This latest rumour swept slowly through the masses. The children sat up and shook their neighbours. They called out to friends who lay nearby, until one boy got to his feet and made an impassioned announcement.

‘The aliens,’ he cried. ‘They’ve landed in Lowerfold Park again.’

The children kicked off their blankets and in less than a minute they were on the move again. They all went hammering back up the hill towards the aliens. They raced up Church Street, past the school and through the park gates. They ran beside the bowling green and the tennis courts. Through the gardens and round the duck pond, under the horse chestnuts and out into the playground, where, at long last, they came face to face with the alien spacecraft as it sat on the ground in all its silvery majesty.

The children skidded to a halt. Those at the back pushed forward to try and get a better view. Those at the front resisted – didn’t want to get too close.

It wasn’t quite as big a spaceship as they’d expected. It was a squat little thing, about ten feet tall with a rounded top. More like a small caravan than a dish or a rocket. And, if truth be told, it was a little lumpy: not half as smooth or sleek as alien spacecraft are meant to be.

But there it sat, as solid and real as the swings and the seesaw, with the sun behind it, which gave it an ominous glow. Nobody said a word. The only sound was the chimes of a church bell, away in the distance.

For quite a while nothing happened. And some of the children began to wonder how long they might have to stand there waiting when, without warning, a hatch in the side of the spacecraft fell open. Not slowly and accompanied by a sinister hissing, like on the telly, but just sort of dropped open and hung there, suspended by what looked like a piece of string.

The children held their breath. Who among them would have the courage to step forward and greet the Martians? Certainly, Daniel Taylor began to wish he’d not been such an eager-beaver the previous day. But as they watched, a foot slowly emerged through the open hatch and stepped on to the tarmac. It wore a silver boot. Then the creature’s backside emerged … an arm … its head. Until the children saw that it was actually Miss Bowen. Miss Bowen setting foot back on Planet Earth.

She may have slipped or simply lost her footing, but to some of the children it seemed as if she’d been rather roughly bundled from the spaceship. An ‘Ooh’ went up from the crowd of infants. Some assumed she was just a bit dizzy from being whisked up and down the universe. As she regained her balance the hatch was yanked back up behind her. Then, deep within the spacecraft, an engine was started and a plume of exhaust fumes crept out from under it. The children shielded their eyes, expecting some blinding, deafening departure, but instead of lifting off the vehicle revved, clunked into gear then promptly headed off across the playing fields and turned down Danvers Street.

Once the spacecraft was gone the children turned their attention back to their music teacher. She stood completely alone. And, one by one, they began to tiptoe in towards her. The woman looked quite befuddled. Sandra Ward, having been the first to raise the alarm regarding Miss Bowen’s abduction, felt quite reasonably that the two of them now had some special kinship and was the first to speak.

‘Are you all right, miss?’ she said, but before the woman could answer someone else called out, ‘Where did they take you?’

Miss Bowen raised a hand to her brow and for a while she just stood there, scanning the horizon.

‘She’s been brainwashed,’ said Theodore Gutch, who considered himself something of an expert on such matters, having read a book on it. ‘They’ve erased her memory.’

And the children feared that their music teacher had been reduced to some sort of zombie – someone who would not be able to tell a crumhorn from a walking stick.

‘What’s your name, miss?’ Daniel Taylor called out softly. ‘Do you remember?’

There was a long pause, during which her health and her whole future as a music teacher seemed to hang in the balance. Then she slowly turned and her eyes finally seemed to focus.

‘Miss Bowen,’ she said. ‘I’m Miss Bowen.’

A sigh of relief swept through the crowd. Miss Bowen was back among them. And the children moved in like a friendly swarm. They took her hands and looked lovingly up at her. And very gently, very quietly, they led her back to the safety of the school.