A‘hearse’ is basically a large black car for ferrying dead people from one place to another, with big windows down both sides so that you can see the coffin, and a handful of men in black suits, sitting bolt upright, to keep it company.

Hearses tend to go very slowly. Hearses just sort of glide along. And as they make their way down the streets they bring a melancholy air along with them, like a big, black cloud blocking out the sun.

It is considered bad manners for other cars to honk their horns or flash their lights at hearses to tell them to get a move-on, just as it is considered bad manners to knock over old ladies or laugh out loud in libraries. When you see a hearse with a coffin on board it is customary to remove your hat and stand to attention while it passes. If you’re not wearing a hat then you should bow your head. This is called ‘showing respect for the dead’, but, in truth, what you’re really showing respect for is Death itself.

The Woodruffs were perfectly suited to undertaking. Old Man Woodruff had a face like a bloodhound and his three sons – Vernon, Earl and Leonard – were about as miserable a bunch of men as you could hope to meet. The Woodruffs hadn’t been the happiest family to begin with. Then Lillian Woodruff, wife and mother, died before her sons had finished growing up, which made a hard life even harder and left a stain of sadness on all four of them.

Old Man Woodruff liked to sit in the passenger seat. He considered it his right as the family elder and reckoned his dour demeanour helped set the right tone. His sons weren’t particularly bothered where they sat, although Vernon did most of the driving, which meant that Earl and Leonard usually ended up in the back.

When they were out in the car it was generally felt that they should look straight ahead and be as impassive as possible. Nose-picking, smiling, yawning and face-pulling were all considered inappropriate. If they passed an old friend in the street, they confined themselves to a curt nod of the head or discreet little wink and any conversation in the hearse itself was conducted out of the corner of the mouth, with a minimum of expression.

But the Woodruffs certainly knew what they were doing. Over the years they must have delivered several hundred, if not thousands, of corpses to their final resting place. When people suddenly found themselves in possession of a dead body their first call was often to the Woodruffs. In certain circumstances a bit of glumness is just the job. But such a reputation was no comfort to Old Man Woodruff on that fateful Friday, when they were out in the country carrying some old-timer to his funeral and Vernon checked his rear-view mirror and found that the car with the old-timer’s family in it, which was meant to be following, was nowhere to be seen.

‘Hmm,’ said Vernon.

‘What do you mean – hmm?’ said his old dad.

‘The mourners,’ said Vernon. ‘They ain’t there.’

If they hadn’t had so many years’ experience behind them Earl and Leonard might have been sorely tempted to look over their shoulder, but all four Woodruffs kept looking straight ahead, despite the fact that there was no one watching them. Vernon gently brought the hearse to a halt and looked hopefully into his mirror, but the car containing the dead man’s family failed to materialize.

‘You great nelly,’ said Leonard from the back seat. ‘How could you lose ’em?’

Vernon hadn’t the foggiest idea.

‘They must’ve taken a wrong turn,’ he said.

Their father was shaking his head most gravely.

‘This is a bad day,’ he said. ‘Very bad. I knew it the minute I stepped out of bed.’

The Woodruffs sat and waited in that country lane for a good five minutes, without a single other vehicle rolling into view. Their only company was a couple of cows who slowly ambled over and poked their heads through the hedgerow to see what was going on.

Eventually, Old Man Woodruff exploded.

‘This is ridiculous,’ he said, and instructed Vernon to drive on. ‘We’ll just have to catch up with them at the church.’

And so they pressed on, down narrow roads which grew steadily narrower, on to lanes which were so rough and bumpy they were barely worth the name. Half-way down a steep hill one of the hearse’s wheels bounced in and out of a pot-hole with such a thump that the coffin leapt up, as if the dead man inside was having seconds thoughts about being buried and had decided to call the whole thing off. Earl and Leonard weren’t remotely troubled by it. They’d been over bigger bumps in the past and, without uttering a word, they both raised a calming hand over their shoulder to stop the coffin hitting them in the back of the head.

Thick brambles began to scratch and screech down the sides of the hearse. Old Man Woodruff was shaking his head again.

‘We should’ve checked the route,’ he said, with great feeling. ‘We should’ve stuck to churches that we actually know.’

Vernon’s confidence, regarding where they were and where they were going, rose and fell just like the lanes along which they travelled. There were also odd moments in which he admitted (if only to himself) that he had no idea where on earth they were. He would have had more hope of finding his way back on to a road he actually recognized if he’d been at the wheel of a car which could have been more easily turned around. The fact that the hedgerows were ten feet tall and prevented him from getting his bearings did nothing but make matters worse.

After wandering round that maze of lanes for a further twenty minutes they finally came out into a clearing on a hillside. Vernon stopped the car. Down to their right they could see the great, wide river. On the far side they could see the roofs of a village and, in their midst, a church steeple pointing towards the heavens.

‘There it is,’ said Vernon. ‘That’s the church we’re after.’

The hearse slowly filled up with an ominous silence.

‘Where’s the bridge?’ said Len.

Vernon jabbed a thumb over his left shoulder. ‘About ten miles thataway,’ he said.

Old Man Woodruff, having only just managed to pull himself together, promptly fell apart again. He dropped his head into his hands and began muttering darkly. Earl was getting royally sick of his dad’s incessant carping and moaning and was about to tell him to get a grip when Leonard spotted a cottage right down by the river.

‘Right,’ he said. ‘Everyone out.’

*

Harold Digby had just finished a plateful of ham and eggs and three slices of bread and butter and was sitting in his favourite chair with a mug of tea in his hand. He was looking forward to a little nap once the tea was inside him. He liked a little snooze after a bit of food. He once closed his eyes about half-past twelve and didn’t come round until getting on for three o’clock and he was wondering what the chances were of him pulling off a record-breaking snooze this afternoon when someone suddenly started banging on his front door.

‘Isn’t that just ruddy typical?’ Harold said to himself.

He put down his mug of tea and got to his feet. He straightened his hair, in case it was anyone important, and opened the door to find four sinister-looking fellows all dressed up in black suits, with a coffin resting on their shoulders.

‘Are you the ferrymaster?’ the old one asked him.

Poor Harold felt quite faint. He somehow got it into his head that Death had come a-calling. That it planned to toss him in its coffin and take him away.

He swallowed hard. There seemed to be no point in lying. ‘I am,’ he said.

‘Good,’ said the old fellow. ‘We’ve got some ferrying for you to do.’

Harold was greatly relieved that his days on earth were not yet over and that he had any number of years still left to set things straight. All the same, he let it be known that he was far from happy taking a dead body in his boat, even if it was a dead body wrapped up in a wooden box.

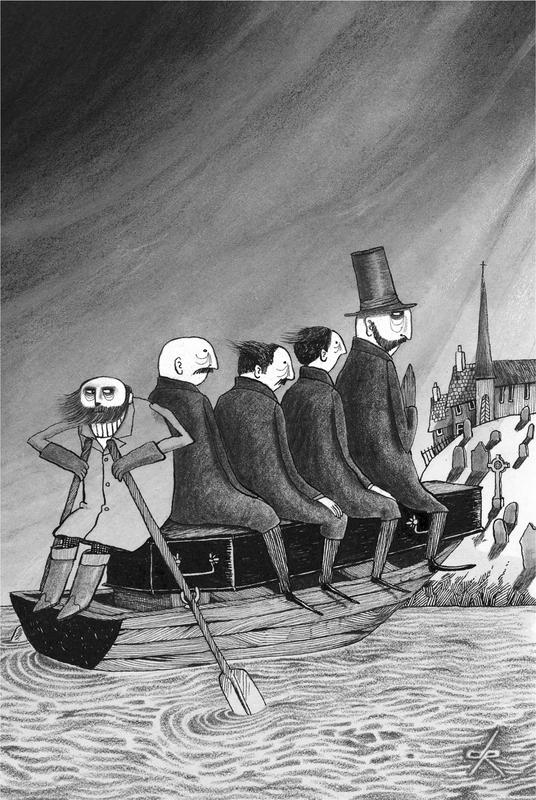

‘Four’s usually the limit,’ he said, as he led the Woodruffs and their coffin down the rickety old pier to where his boat was tethered.

‘Think of him as luggage,’ said Earl, which seemed to shut him up for a while.

Getting the coffin on to the boat wasn’t a problem. The problem was finding a place for everyone to sit. The coffin fitted quite snugly across the two crosspieces but the boat wasn’t particularly wide, so the only way to get everyone on board was for them to squeeze in around it and hang over the sides.

Old Man Woodruff insisted he sit up front, just like in the car. The others tried several different ways of distributing themselves about the boat, without success. And all the time, their dad kept saying how they were late and that people would be waiting, until finally Harold Digby took charge of the situation and announced that as he’d have to sit astride the coffin to do the rowing, the only sensible thing was for the others to do the same.

Which is how they came to set sail with all five of them straddling the coffin, like some gruesome fairground ride. The moment they left the quay everybody fell silent. The Woodruffs were concentrating with all their might. The whole arrangement was a bit top-heavy, but Mister Digby assured everyone that as long as they sat quite still he’d have them over the other side in no time at all.

They were doing very well until they got about half-way over, with Mister Digby rowing and facing back towards his cottage and the Woodruffs facing the other way. They were travelling about as smoothly and quietly as they did in their hearse when Leonard started shifting and squirming.

‘What’s going on back there?’ said Old Man Woodruff.

‘It’s my underpants,’ said Leonard. ‘They’re riding right up.’

Everyone told him to sit tight until they’d got where they were going. But Leonard couldn’t think of anything else. He lifted his backside until it was clear of the coffin, hooked a thumb under the offending piece of underpant and yanked it clear. But when he sat back down he misjudged his landing and slipped – quite violently – to the right. The others leant to the left, to try and compensate, but overdid it. The boat tilted one way, then the other, and with each swing it gained momentum, until it finally went right over and deposited the Woodruffs, Harold Digby and the coffin into the river.

A terrible splashing and thrashing ensued, as each man fought to keep his head above the water. But as any lifeguard worth his salt will tell you, it is one thing to swim in nothing but a pair of trunks and quite another to do so fully clothed. Leonard, Earl and Vernon weren’t particularly good swimmers. Even Mister Digby was not as good as one might expect. But Old Man Woodruff had never learnt a stroke and all he could think to do was kick his feet and claw at the water.

‘Doggy-paddle … doggy-paddle,’ he said out loud, to try and give himself some encouragement.

The boat was upside-down and already twenty yards from them. The only thing left floating that they could get a hold of was the coffin and once they got a hold of it they weren’t about to let it go.

The coffin rocked and bobbed as each man got an arm around it, but it never threatened to let them down. When all five of them were attached they took a minute to clear their lungs and catch their breath.

‘Are you all right, dad?’ said Leonard.

He said he was, but that the sooner they were out of the water the better. And without anyone in particular suggesting it one or two of them started flapping their feet, and soon all five of them were slowly propelling the coffin the rest of the way.

‘Kick,’ said Old Man Woodruff, who was suddenly an expert swimmer. ‘Kick out with your feet.’

When they got to the other bank they stood around for a while, cursing and dripping. And when the Woodruffs had finally agreed some sort of compensation with Mister Digby and done their best to smarten themselves up a bit, they lifted the coffin back on to their shoulders and headed up the hill.

There was a fair-sized crowd waiting for them. As they approached the church an old lady, who looked most upset and was therefore most likely to be the dead fellow’s widow, headed over towards them. They came to a halt at the church gates and the old woman looked them up and down. Their suits were sopping wet and their hair was plastered to their heads. As they stood there, small pools of water gathered around their feet.

‘Where on earth have you been?’ she asked Old Man Woodruff.

He cleared his throat and mustered as much authority as he could in the circumstances.

‘We checked the records, ma’am,’ he said, ‘and found no sign of a christening. We thought it best to baptize him – just to be sure.’