“Only today, now that almost the whole world has succumbed to ape-nature – right up to the Germanic countries which have not been fully spared either – does the truth begin to dawn on us, that we are lacking a certain divine humanity in a general flood of ape-men. But it will not be long before a new priestly race will rise up in the land of the electron and the Holy Graal …”

– Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels, 1905

On Christmas Day, 1907, the defrocked monk Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels hoisted a swastika flag over Castle Werfenstein in Upper Austria. By this symbolic birth-ritual, Lanz raised up powerful energies that would either recreate the primordial Aryan empire of Thule or leave Germany a blasted ruin. Although a practicing mystic, and an assiduous student of the occult, Lanz may not have known just what forces he was unleashing. At the time, his action seemed indistinguishable from the rituals, symbolic concerts, poetic evocations, and other seemingly petty activities common all across Germany and Austria in the three decades before World War I.

Although German nationalism awakened during the Napoleonic period, the German nation spent most of the 19th century in frustrated fragmentation. Following the creation of the German Empire in 1871, romantic German nationalists relieved these frustrations in paroxysms of heroic myth-making about the pre-Roman, “purely Teutonic” past. All over Europe, anthropologists, linguists, archaeologists, and other scholars were piecing together new national histories using the newest tools in their field. Their findings became national propaganda, providing a glorious past and proving their ancestral rights to any disputed territory. Poets, mystics, and politicians alike used these histories to create epics, rituals, and pretexts for national expansion. Again, thanks to the delayed realization of an “authentic” unified German nation, the German expression of these trends was more extreme than most. Also, since German nationalism defined itself in opposition to the invading French revolutionaries, it took on a strongly anti-modern, anti-Enlightenment character, seeking instead the pure, untainted wisdom of the Volk.

By the 1880s, scores of völkisch societies existed in Austria and Germany. The word völkisch has no specific translation in English: depending on context, the words “folkloric,” “populist,” and “ethnic” could equally apply. These societies studied Germanic mythology, celebrated heroes and legends, and tried to imbue everything from forestry to sing-alongs with nationalistic significance. As Germany and Austria urbanized, and as rival nations began to ally against them, the völkisch societies rejected “cosmopolitan” influences and valorized the “eternal struggle” of the German people against Latin and Slavic influence. Their publications and poetry contrasted the glorious fantasy of Germany’s pagan past with the uncertain, dirty reality of Germany’s Christian present. Some sought a renewal of pagan nature-worship, while others merely wanted to purify Germany of all foreign influences.

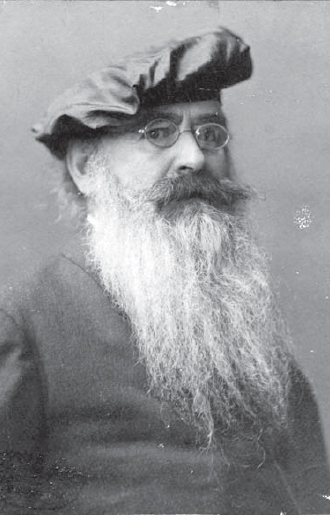

Guido von List (1848–1919), founding father of the völkisch movement, is shown here in 1913. By this point, List was devoting his energies to further deepening the connection between Teutonic lore and theosophy in a series of ‘Ario-Germanic research reports,’ and passing on his wisdom to a secret order of initiates called the Hoher Armanen-Orden (High Armanen Order, HAO). His primary disciple after 1911 was a fellow reincarnated clairvoyant calling himself Tarnhari, who later became a key member of Dietrich Eckart’s circle. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-2005-0814-501, photo: Schiffer, Conrad H.)

Guido List came to the forefront of Vienna’s völkisch community with the publication of his novel Carnuntum in 1888. Fond of long nature walks and an avid sportsman, List wrote primarily travel journalism, spangling his narratives with lore about the pagan past and folk traditions of the countryside. Carnuntum was different: a rousing historical novel about heroic Germans smashing the decadent Roman state and building a pagan utopia. Best of all, List vouched for its accuracy since its events came to him in a clairvoyant vision! The novel’s success caught the eye of the pan-German and anti-Semitic publishers Georg von Schönerer and Karl Wolf, who commissioned more fiery works from List.

In the 1890s, List wrote novels, poems, and plays, and lectured about the ancient German religion of Wotanism and its elite and holy priesthood. Searching for details about this hidden and suppressed belief, List began to read more deeply in the occult. He encountered theosophy during this time, and it fundamentally reshaped his views. Founded by the Russian adventuress Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, theosophy blended the Hindu cosmology of cyclic time with a sort of Darwinian notion of competing and changing “root-races.” In her books Isis Unveiled (1877) and The Secret Doctrine (1888), Blavatsky explained that theosophy was a scientific truth expressed in religious terms. Hidden for millennia, Secret Masters in Tibet had revealed “the Occult Science” to her now that mankind was capable of comprehending it.

This illustration, captioned “Im Reiche der Runen” (In the realm of the runes), comes from Geheime Mächte? (Secret Powers?), a picture book on the history of magic published in 1931 by an Austrian tobacco company. Note the swastikas spinning in both directions; there is no historical difference in usage between “left-handed” and “right-handed” versions of the symbol. (Mel Gordon Archive)

Most significant to List was Blavatsky’s revelation that true mankind comprised several different sub-races, all offshoots of the Aryan root-race that had emerged from the Atlantean root-race 100,000 years ago. Of those sub-races, the most recent and elevated was the Teutonic race, which had migrated to Germany from the “City of the Bridge” in Central Asia in 20,000 BC. Other seeming humans were actually descended from other non-human root-races: the Australoid and Dravidian peoples were degenerate Lemurians, while the Mongolian, Amerind, Malay, and Jewish peoples were degenerate Atlanteans.

In 1902, List underwent an operation to remove his cataracts, and was blinded for 11 months. During this time, he pondered his new theosophical learning and meditated on the sacrifice of Wotan, who according to Teutonic myth gave up an eye in exchange for true wisdom. While blinded, his “inner eye” opened, and List had his own revelation: like Wotan, he received the secret of the runes. Wotan’s runes were more than just the alphabet used for Germanic inscriptions – they were a secret language of power and their symbolic shapes were the underlying geometry of creation. In 1903, List (by now using the aristocratic “von” in his name) sent a preliminary version of his rune discoveries to the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Vienna. The Academy returned his manuscript without comment, much less publication.

The insult to List became a cause célèbre for the völkisch movement. In 1905, a number of supporters, including the mayor of Vienna, signed a petition calling for the creation of a “List Society” to promote his studies. With such backers, List produced more work uncovering the runic influence in heraldry, architecture, and place names. He also expanded his clairvoyant readings of the Austrian landscape, revealing the history of the Armanenschaft, the sacred priesthood of Wotan. This priesthood of initiates knew the true meaning of the swastika symbol of the sun: it represented the “invisible primal fire” underlying all creation. Most importantly, the Armanenschaft ruled the ancient Germans as benevolent dictators, using their occult powers to protect and expand the homeland. In his 1908 work Das Geheimnis der Runen (The Secret of the Runes), List spelled out these occult powers: by a combination of meditation, physical culture (such as yoga), and vocalization, the Armanen could re-tune the world to its true runic nature, and change it.

Born Adolf Josef Lanz in 1874, Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels proudly signed the List Society petition. He and List regularly exchanged visionary interpretations of the Austrian countryside and theosophical arcana; Lanz coined the term “Ariosophy” to refer to their specific version of Aryan theosophy. Expelled from a Cistercian monastery for engaging in “carnal love,” Lanz turned from orthodox religion to mystical journalism. He started an occult magazine in Vienna, Ostara, which claimed a circulation of 100,000: its readers included a young art student named Adolf Hitler.

Lanz’ magnum opus Theozoologie laid out his own visionary discovery, which he buttressed using Gnostic texts and other recondite sources he had uncovered while still a Cistercian monk. According to Lanz, humanity was divided into two main strands. The pure Aryans were god-men (“Theozoa”) with telepathic and other occult powers, who came from other stars (or dimensions) and bred by electricity. Sadly, they corrupted their lineage by breeding with beast-men (“Anthropozoa”), who survive to this day both in mixed-blood descendants (the vast majority of humans) and in pure monstrous form. Lanz called for eugenic attempts to breed back to a true Aryan race, essentially the future SS Lebensborn (Spring of Life) campaign; and for the sterilization and eventual extermination of the Anthropozoa-descended, prefiguring the Holocaust.

Depictions of the swastika go back at least 10,000 years. To the Greeks, the Japanese, the Navajo, and many other cultures, the swastika represented fire, fertility, the sun, and the circling stars around the North Pole. It blazoned forth at the court of Charlemagne and in temples to Thor. The word “swastika” comes from a Sanskrit phrase meaning “be well,” but in German it was called the Hakenkreuz, the “hooked cross.” This fit in well with the völkisch agenda of altering Christianity and replacing it with proper Aryan paganism.

The French anthropologist Émile Burnouf declared it the soul-symbol of the Aryan race in 1852 and the pan-Germanist Georg von Schönerer adopted it as a völkisch symbol in 1879. To List, the swastika (or fyrfos, as he called it) represented race fertility, immortal power, and national return. He added it to the orthodox rune list as a hidden rune concealed between the 17th and 18th runes; it thus also stood for occult energy.

Hence, the Thule Gesellschaft (Thule Society), a self-described “study group for German antiquity,” adopted the swastika as its emblem in 1918, and when its erstwhile political wing, the Nazi Party, was looking for symbols, the swastika was close at hand. Hitler took credit for the final design of the Nazi flag (which debuted on May 20, 1920), basing it on a local Party emblem designed by a Thule member named Friedrich Krohn. The effect, as Hitler said later, “was as if we had dropped a bomb.”

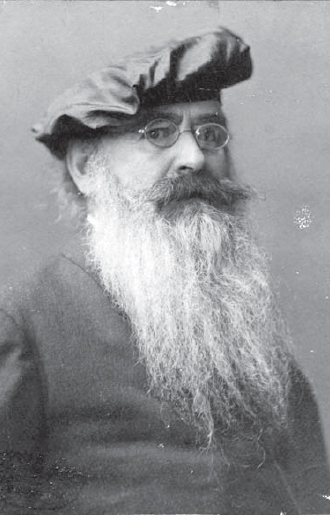

Járg Lanz von Liebenfels (1874–1954) wearing the monastic robes of his neo-Templarist order, the ONT. In 1894 at Heiligenkreuz Abbey, while still a Cistercian monk, Lanz received an “illumination” at the tomb of Berthold von Treun, a Templar knight. Von Treun’s gravestone depicted a knight (or perhaps the prophet Daniel) trampling a writhing dragon, an allegory Lanz extended to deduce an ongoing war between Aryans and subhuman beasts. (PD-US)

To accomplish these vast goals, Lanz revived the medieval knightly order of the Templars, who he believed guarded the Aryan lineage in celibate isolation until the beast-men who ruled the Church destroyed them. Lanz explained that the Templars (whom he conflated with the Teutonic Knights) sought a “greater Germanic order-state,” stretching across the Mediterranean and deep into the East. To accomplish this goal, they sought the Holy Grail, an “electrical symbol” of the “pan-psychic powers” of the Aryan race. He designed a swastika flag for his Ordo Novi Templi, or Order of the New Templars (ONT), and raised it in 1907. Although the ONT attracted a number of Austrian occultists and völkisch enthusiasts, it didn’t accomplish Lanz’ expansive ambitions. Instead, it put on folk-music concerts, held quasi-Freemasonic ritual meetings, conducted anthropological and genealogical research, and founded “utopian Aryan” communities in spots of great natural beauty. It would be another order that actually changed Germany.

By c.1910, the völkisch societies had identified two main enemies of their pure Aryan Germany: the Freemasons and the Jews, who embodied both French Enlightenment ideas and cosmopolitan capitalism respectively. The industrialist Theodor Fritsch, whose explicitly political Hammerbund anti-Semitic movement was going nowhere, decided he needed a counter-Masonry to promote anti-Semitism. In 1911, he recruited the Magdeburg bureaucrat Hermann Pohl to organize this Germanenorden (German Order) along the lines of List’s and Lanz’ researches.

The ceremonies of the Germanenorden blended völkisch Wagner with quasi-Masonic rituals lifted from the ONT. Members had to be good-looking, well-off, and pure-blooded Aryans; these requirements slowed recruitment considerably. The outbreak of World War I splintered the Germanenorden, as half its membership found themselves in the trenches. Pohl dithered until a rebellious faction forced his resignation in 1916; he responded by declaring himself the head of a new Order, the Germanenorden Walvater von Heilige Gral (German Order of the All-Father of the Holy Grail). He took the seals and other magical regalia of the Germanenorden with him, and started looking for recruits in fresh territory: Munich.