“[Hitler] has set us the goal for our generation to be a new beginning – he wants us to return to the source of the blood, to root us again in the soil – he seeks again for strength from sources which have been buried for 2,000 years.”

– Heinrich Himmler, January 1935

On August 4, 1939, at 5:10 p.m., a Junkers Ju 52 passenger aircraft taxied to a stop at Oberwiesenfeld Airport in Munich. Waiting on the tarmac were Heinrich Himmler and Karl Wolff, eager for a first-hand report of the Ahnenerbe’s latest triumph. The propellers stopped, the doors opened, and in his dress-black Allgemeine-SS uniform Hauptsturmführer Ernst Schaefer stepped down to meet his masters. He had returned to Germany despite every bureaucratic obstacle the fading British Raj could throw at him, returned a hero after 13 months in Tibet. In his black-gloved hands he held an idol carved from meteoric iron, fallen to Earth in the Gobi Desert in 20,000 BC – the very place and time that the Teutonic race had begun its migration to Germany, according to theosophical lore. The idol’s Nordic features, Tibetan headgear, and swastika breastplate proved the theosophists correct: Tibet and Germany were two branches from the Aryan root-race that had been born in Inner Asia!

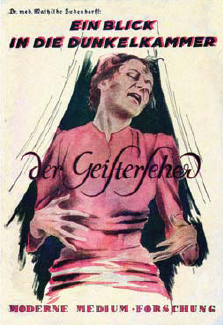

Dr. Mathilde Ludendorff (1877–1966) met General Erich Ludendorff in 1923 and married him in 1926, providing her with a vastly larger audience for her völkisch beliefs and conspiratorial theories. She was a devout pagan, seeing Christianity as a Jewish cult, but she also deprecated the occult, which she derived from Semitic and other anti-Germanic sources. She helped turn Ludendorff’s personal mass-conspiratorial movement, the Tannenbergbund, into a pagan society devoted to Gottserkenntnis, or “God Knowledge.” (With 100,000 followers in 1925, it rapidly tapered off in rivalry with the Nazis.) Among her bêtes noirs were the Jesuits, the Masons, the Dalai Lama (whom she fingered as the head of the global Jewish conspiracy), yoga and Hinduism in general, and spiritualists. Her 1937 book Ein Blick in die Dunkelkammer (A Moment in the Dark Chamber) attacked mediums and the parapsychological researches of Albert von Schrenck-Notzing. (Mel Gordon Archive)

A renowned hunter and ornithologist, Schaefer had been part of two previous expeditions to Tibet, in 1931 and 1934–35 under the American adventurer (and future OSS officer) Brooke Dolan II. Schaefer joined the SS in March 1933, one of the “March violets” who suddenly sprouted Nazi convictions when Hitler came to power. Trumpeting his success in his second expedition, he sought Ahnenerbe support for a planned third expedition under his own leadership. He expatiated on the Aryan symbols he had seen in Tibetan graves, and on the prestige he could bring to German science. After meeting Schaefer, Himmler agreed to sponsor the trip on two conditions: the entire expedition complement must be SS personnel, and Karl-Maria Wiligut must approve of Schaefer. In May 1937, Schaefer and Wiligut met at the latter’s Grunewald villa. In an opium haze, the aging clairvoyant slipped into a trance and began listing, and then describing in detail, lamaseries and sacred places in eastern Tibet, places Schaefer had visited or dreamt of. Schaefer later wrote that it felt as though Wiligut was inside his mind, comparing the experience to the legendary telepathic abilities of the Tibetan adepts.

After that meeting, Schaefer transformed from a cynical scientist hoping to exploit Himmler’s Asiatic fixation to a true believer in Aryanist magic. Even the tragic death of his wife in a shooting accident on a remote lake – Schaefer dropped his shotgun in the boat and it went off – could not stop him. (A confidential OSS report suggested Herta Schaefer’s death was actually a human sacrifice, much as Agamemnon sacrificed Iphigenia before the attack on Troy.) As he pored over the occult manuscripts and secret research papers in the Ahnenerbe library, Schaefer realized that his idealized “Forbidden Kingdom” of Tibet was only the surface and shadow of the true Forbidden Kingdom in Central Asia: the hidden empire of Agartha.

Agartha was first revealed by Louis Jacolliot, a French colonial jurist in Chandernagore, a French colony in India. In Les Fils de Dieu (The Son of God; 1873) he told the story of “Asgartha,” the solar capital of ancient India. In his telling, when the Aryans conquered Asgartha in 10,000 BC, its priestly rulers initiated the invaders as their warrior caste. The occultist Alexandre Saint-Yves d’Alveydre showed a different face of “Agarttha” in his Mission de l’Inde (Mission of India; 1886). Trained in Sanskrit and in the elder alphabet of Vattanian by a mysterious Indian guru, Saint-Yves described an ancient subterranean kingdom beneath the Himalayas powered by electrical force, ruled by the Sovereign Pontiff. The legend of Agartha went underground for 40 years, surfacing again in the travel narrative Beasts, Men, and Gods (1922) by the novelist and adventurer Ferdinand Ossendowski. Having barely survived a civil war in Mongolia, Ossendowski reported that all of Inner Asia was in a ferment, expecting the King of the World and his supermen to emerge from his cavern empire of “Agharti” deep inside the earth. However it was spelled, Agartha was clearly a force to be reckoned with.

While Ossendowski was dodging communist cavalry in Mongolia, another Asian traveler was teaching Rudolf Hess everything he knew. Karl Haushofer, a Bavarian general and professor of geopolitics, had been Bavaria’s military attaché in Japan from 1908 to 1910. While there, he had been initiated into the Ryokuryūkai, and possibly met Gurdjieff in China. He also met with the Ryokuryūkai agent Narita Yasuteru, who had visited Tibet in 1901 and contacted the mysterious eminence grise of the Tibetan priesthood known as Gyanggu Chhashup Pönpo, or the Man With Green Gloves. Between Haushofer’s return to Germany and his service in World War I, he formulated his geopolitical theories of Lebensraum (living space) and the crucial strategic position of Central Asia in any coming world conflict. After the Armistice, Haushofer returned to academia; Hess became his assistant and intellectual heir. Hess introduced Haushofer to Hitler in Landsberg Prison in 1923 after the failed Beer-Hall Putsch; whether their talks covered more than global strategy and the virtues of the Japanese military state remains unknown.

The Man With Green Gloves had sent his message west. Another failed putsch sent the reply east. In 1920, the Ariosophical stormtroopers of the Ehrhardt Brigade instigated the so-called “Kapp Putsch” in Berlin, briefly seizing the capital from the Weimar government until they were forced to step down four days later in the midst of a general strike. Their propaganda minister, a Hungarian adventurer, spy, and occultist (initiated into Aleister Crowley’s magical Ordo Templi Orientis (OTO)) named Ignacy Trebitsch-Lincoln, fled the ensuing welter of betrayal with a valise full of secret documents. When he surfaced in China in 1925, it was as a theosophical Buddhist lama variously named Chao Kung or Dordje Den. He had made his way to Tibet with the Thule’s counter-offer, and it was accepted. During the years between 1928 and 1932, Trebitsch-Lincoln traveled between China and Europe, meeting up with his fellow Kapp-putschist (and sometime Hitler supporter) General Erich Ludendorff, himself converted to runic Ariosophy in 1926 by his second wife Mathilde. Trebitsch-Lincoln moved through all esoteric circles, from the Polaires in France to Hanussen’s “Palace of the Occult,” his agenda always mysterious. During those same years, reports and rumors flew that the Man With Green Gloves was seen in Berlin – possibly Trebitsch-Lincoln had opened the way for the master to bilocate at least his astral form to the burgeoning sorcerous capital of the West. But some things could only be accomplished by a meeting in the flesh.

Although no records survive of the meeting, SS Hauptsturmführer Ernst Schaefer likely met Gyanggu Chhashup Pönpo, the Man With Green Gloves, on March 25, 1939 in the fabled Black Lamasery somewhere in the Yarlung Valley near Yumbu Lagang in southeastern Tibet.

The lama’s dress is speculative, based on that of the Panchen Lama; other reports describe a figure swathed in maroon robes with only green gloves and a “pale, waxy, mustached face” visible. Schaefer wears his black Ahnenerbe-SS uniform; SS Obersturmführer Karl Wienert, at parade rest behind him, remains in the expedition’s normal garb. From the cessation of Schaefer’s and Beger’s reported discussions of the yeti after their return from the Yarlung Valley, presumably there were yeti present at the meeting, perhaps as representatives of the Third Root Race.

The Japanese invasion of China in 1937, while welcome to Himmler for racial reasons, blocked Schaefer’s preferred route for the SS Tibet Expedition. Now, it would have to enter the Forbidden Kingdom through British India, which meant keeping a lower profile. Schaefer obediently downplayed the involvement of the Ahnenerbe in his mission planning and support, even printing two sets of letterhead (with and without the phrase “under the patronage of the Reichsführer-SS Himmler and in connection with the Ahnenerbe”) for his renamed “Deutsche Tibet Expedition Ernst Schaefer.” However, Schaefer’s agenda and his personnel remained Ahnenerbe to the core.

Along with his cameraman and entomologist Ernst Krause and his technical staff officer Edmund Geer (both SS men), Schaefer selected two other key specialists. SS Untersturmführer Dr. Karl Wienert was the team geophysicist and geologist. A pupil of Germany’s premier Tibetan explorer Wilhelm Filchner, Wienert was an expert in geomagnetic mapping. An intensive Ahnenerbe course trained him to map ley lines and other occult forces, and briefed him on the importance of finding the gateway to Agartha. The FKH had been searching for a more convenient opening to the inner world in Sicily and Greece, but some force had apparently closed those ancient conduits of chthonic power. If Germany was to harness vril or ally itself with a race of advanced Aryan supermen, it would have to make a pilgrimage to the source of life, Tibet.

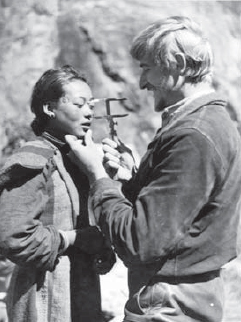

Himmler selected a section head in Wiligut’s RuSHA, SS Untersturmführer Bruno Beger, to be the team’s anthropologist and race specialist. Beger’s consuming passion throughout his career was the determination of empirical physical differences between the Nordic and Jewish races. In the Himalayas, he measured the skulls and limbs of the people he met, looking for traces of Aryan blood left over from the dawn of mankind. (In 1943, the same urge led him into eager partnership in Sievers’ and Greite’s program of anatomical mass murder.) He and Schaefer discussed the yeti, that mysterious “Wild Man of the Snows.” Schaefer was certain the yeti was an unknown species of bear; Tibet, as the place Ariosophists theorized that evolution began in this aeon, must logically have produced hundreds of species unknown in lower lands. Beger was not so sure; he had also heard it called the mi-gö, a name he derived from Aryan roots meaning “the changing horror.” Perhaps the supermen of Agartha emerged to kill subhumans in the ice.

SS Tibet Expedition personnel, from left to right: staff officer Edmund Geer, geophysicist Karl Wienert, entomologist Ernst Krause, anthropologist Bruno Beger, leader Ernst Schaefer. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 135-KA-03-076, photo: Krause, Ernst)

Bruno Beger taking skull measurements in Sikkim. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 135-KB-15-089, photo: Krause, Ernst)

The British resident in Sikkim on the Tibetan border attempted to stall Schaefer’s expedition, but the explorer would not be hindered by bureaucrats. While in London, Schaefer had met with Sir Francis Younghusband, who had invaded Tibet for Britain in 1906 and 30 years later was promulgating belief in stellar gods who controlled the Earth telepathically. Younghusband had told Schaefer simply to “sneak across the border,” and on December 20, 1938, bolstered by a polite invitation to visit a local potentate, Schaefer did essentially that.

Inside Tibet at last, the expedition could begin its real work. Schaefer discussed the power of the swastika and the hateful qualities of British and Chinese imperialism with the Reting Rinpoche, regent for the as-yet unmanifest Dalai Lama. Wienert set about charting the magnetic deformations around Tibet; he spent the party’s two months in Lhasa mapping the ley flows to determine the specific global chakra point that would mark Agartha. In a tiny lamasery tucked under the eaves of the Potala, Wienert consulted mandalas and set compasses by a small meteoric-iron idol the monks were surprisingly eager to give up. Beger had his own successes: in addition to many more physical casts and measurements, he managed to obtain a version of the Kangyur, the compiled wisdom of Tibetan Buddhism. The copy he received included a black terma, dark wisdom revealed by a Secret Master: specifically, ratios and chants found in the Cryptical Books of Hsan, which supposedly predated the destruction of Lemuria.

With Wienert’s measurements and the hints teased out of Beger’s terma, Schaefer led his men to the fortress of Yumbu Lagang, the oldest building in Tibet. Here, the first Tibetan god-kings had descended on a golden rope from heaven and uplifted the sub-creatures dwelling there by mating with them. In these hills, concealed by a vibratory barrier, lay the Hidden Lamasery of the Man With Green Gloves, gatekeeper of Agartha. Schaefer and his team proved their worth by finding the entrance, and the legate of the King of the World welcomed them to his sanctum. No record remains of that meeting; presumably, Schaefer agreed that Nazi Germany would play the role of the ancient Aryan warriors of “Asgartha” long ago: become the earthly army of the Secret Empire in exchange for the power of the gods. In token of this agreement, Schaefer received a phurba, or sacred dagger, made from an unknown metal. In Tibetan Bön practice, the phurba both represents and controls powerful demons or thought-forms. The phurba Schaefer received contained these wrathful energies, penned in a trapezohedral geometry that may have also encoded the true secret of vril. Whatever it contained, it was enough. Less than a month after Schaefer brought it back to Berlin, Germany was at war with the world.