An exterior nest box with a hinged wall allows easy egg collection, even for children.

Chickens will lay eggs in any number of places, convenient or inconvenient for you, safe or unsafe for the eggs. A well-built nest box will not only encourage them to lay those eggs in a secure spot but also make for easier collection on your part.

The best nest box meets three criteria: it is good-looking, easy to reach, and easy to operate. Ours became such a focal point of our yard that Chris (who in our household division of labor is the livestock manager) asked me (the facilities manager) to install a stepping-stone path leading up to it.

An exterior nest box with a hinged wall allows easy egg collection, even for children.

As we prepared the nest box project, we put a lot of thought into the design so it would reflect all our concerns:

A nest box with a wall that opens as a hatch lets humans (especially kids!) meet chickens in a more controlled environment.

To answer our questions about the basics, we started with what a hen looks for in a nest box.

How many? A hen requires a nest box only long enough to plunk herself down and lay that day’s egg. That means you don’t need a separate box for every hen; in fact, you’ll need only one box for every three to five hens.

Where to locate them? The hen wants someplace that’s dry, dark, and out of sight of predators.

How big? She wants it big enough yet cozy. A one-foot cube open on one side works well. For bigger breeds, the box can be up to 14 inches on a side; for bantams, it can be as small as 8 inches. But many folks keep a variety of hens happy with all boxes 12 inches on all sides.

Many chicken-keepers mount nest boxes inside the coop, either set on the floor or attached to an inside wall. This is one valid option, with at least three downsides. The top of the nest box offers a surface on which chickens can roost and deposit poop all night (one more surface for you to clean). The coop must be big enough for you to enter (more time and money). Then when you do enter the coop to gather eggs, you get your shoes all poopy before you walk back to the house to cook an omelet (say no more).

Therefore, whoever came up with the idea of putting nest boxes on the outside of a chicken coop should get a medal. And a pension. And a monument on the National Mall. It’s a great time-saver.

A nest box on an exterior wall of the coop lets you pop out your back door to gather eggs in slippers, bare feet, or your best shoes without getting filthy.

A nest box on an exterior wall of the coop — a wall that is also outside the pen — lets you pop out your back door to gather eggs in slippers, bare feet, or your best shoes without getting filthy. Chris and I both keep a pair of muck boots by the back door to wear on the rare occasions when we enter the pen to deal with the feeder or waterer, but we don’t have to slip them on and off for our more frequent excursions to gather fresh eggs.

An exterior nest box also enabled us to build a smaller, less expensive chicken-scale coop. Think about the cumulative time and aggravation saved over years and years by not opening the coop door or pen gate (“Don’t you girls sneak past me now!”) each time you simply want to gather eggs. Finally, if the nest box is protruding from an exterior coop wall, the hens can’t roost on it.

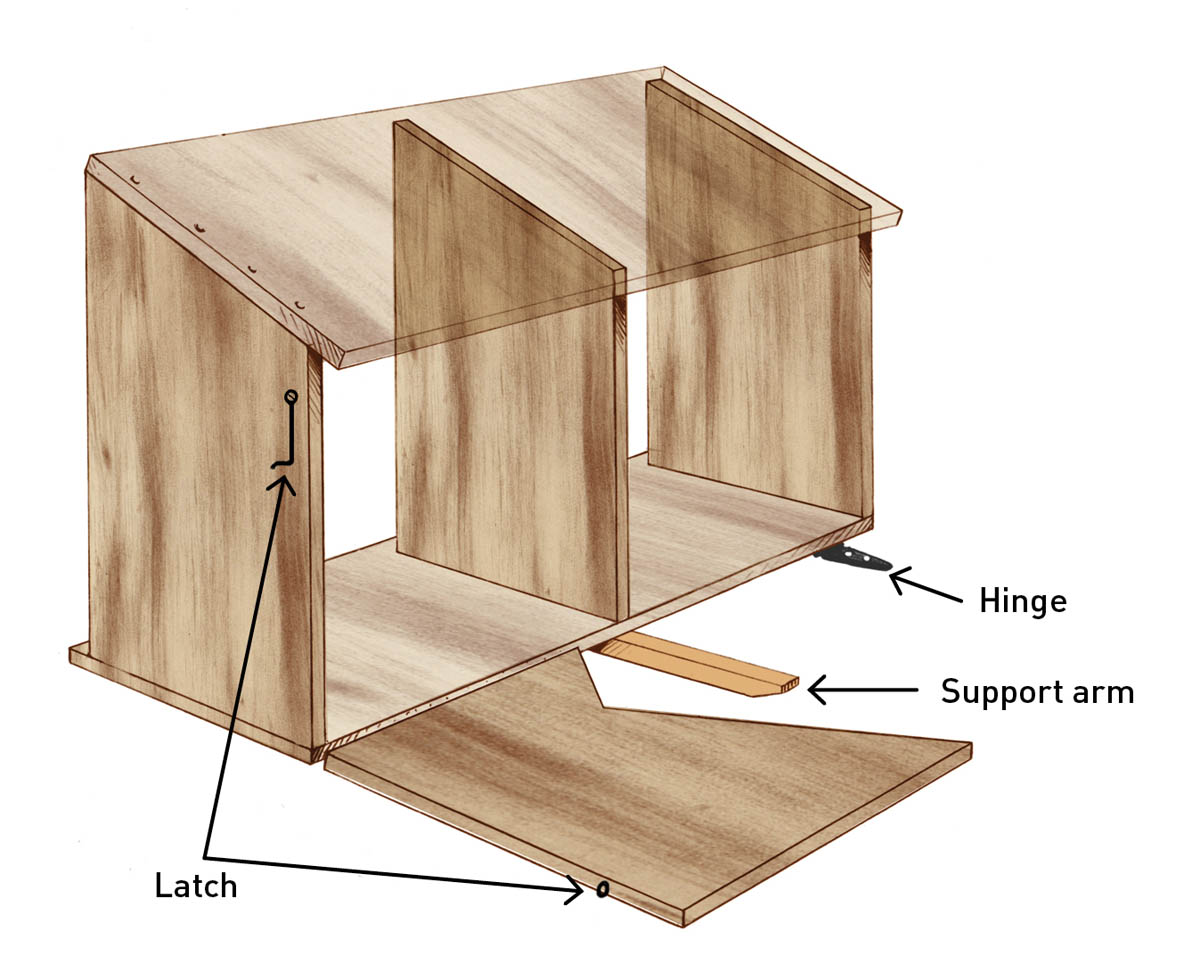

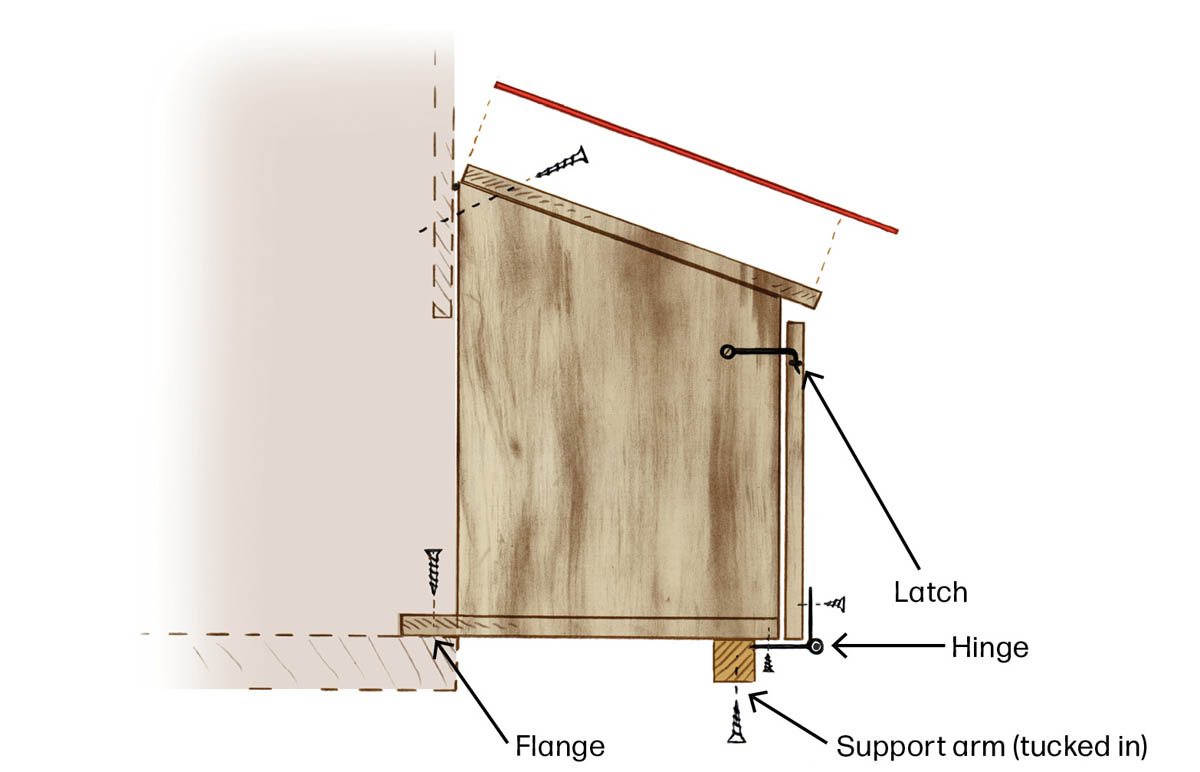

The exterior wall of the nest box is a cleanout hatch when it’s hanging straight down. When resting on a swiveling support arm, it becomes a table for egg gathering.

Before building our coop, Chris and I attended many coop tours and scoured many books and websites. When exterior nest boxes showed up, nearly all provided access through the roof of the box, which was hinged like a toolbox lid. Most of these henkeepers acknowledged that rain often leaked through the hinged edge of the roof lid where it met the wall of the coop.

Closer view of the support arm, which swivels around a screw through its center.

One henkeeper, however, placed the hinges on the bottom edge of the outer wall of her nest box so that it opened like a breadbox. I still recall how excited I was when I saw this simple yet remarkable improvement. I’ve taken to calling that kind of hinged wall a hatch. (Appropriate for hens, no?)

This arrangement keeps the hatch secure against drafts and critters. When Chris and I want to collect eggs or clean the nest boxes, we have easy access and good visibility into the coop.

For the hatch to form a counterlike surface when it’s open, you’ll need a wooden arm that will swing out under it for support. I use scrap pieces of 2 × 2s, but any dimension will do.

I used two arms on this nest box, in an overabundance of desire for symmetry. One support arm will do just fine.

With the support arm in place, the hatch can become a counter on which you can set your egg carton.

As a final touch, we dressed up the nest-box hatch with a drawer pull. It’s merely ornamental, as it takes two hands to unlock the hasps and open the hatch, but it fits one of our design goals: it’s cute.

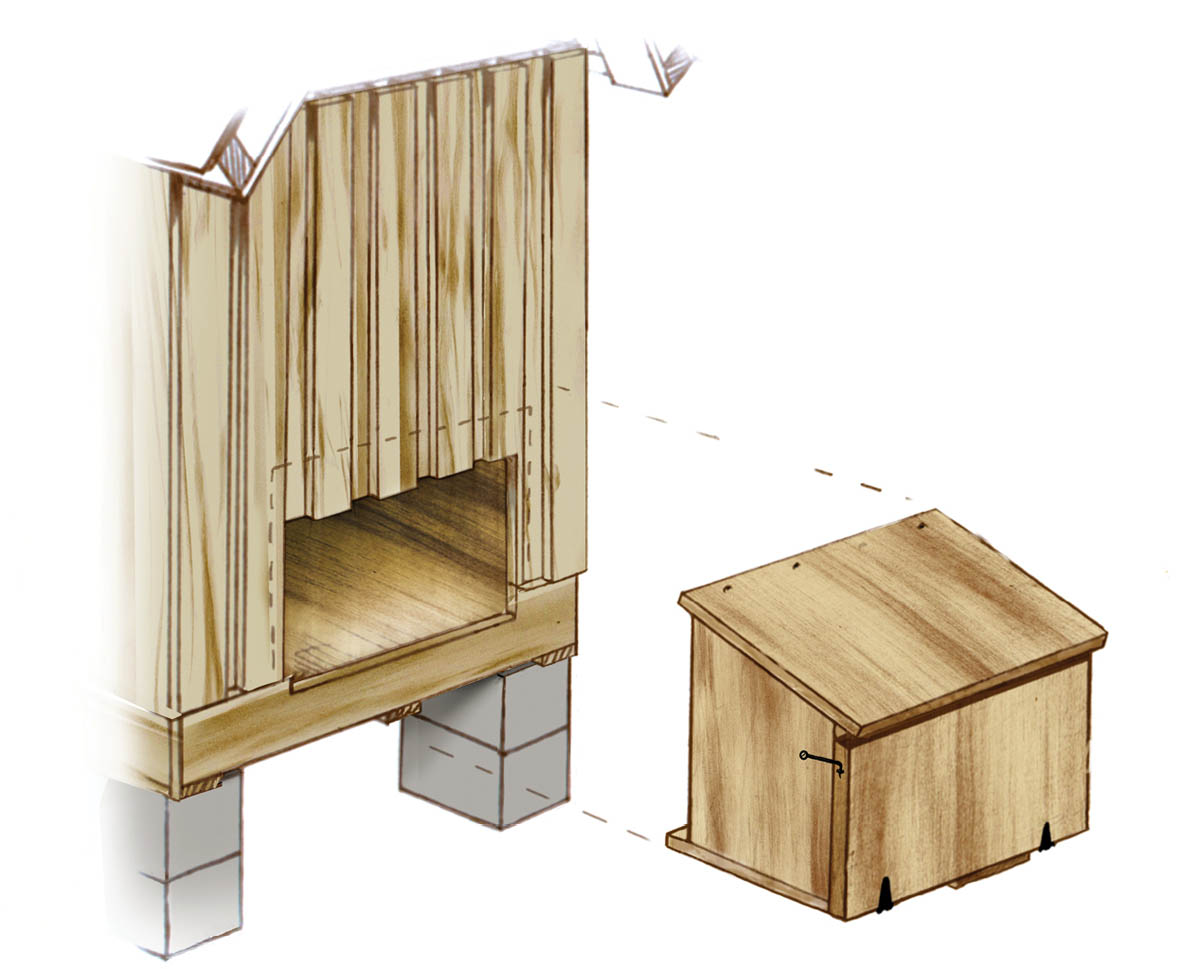

We attached our nest box to the coop so that its bottom is hip-high for me and chest-high or head-high for neighborhood kids: in other words, the floors should be is 18" to 36" from the ground. At this height children can help sweep the nest boxes clean, gather eggs unassisted, or even meet a chicken face to face.

If you’re at the open nest box long enough, one or more hens will come into the coop and then into the nest box to investigate the possibility of treats. This can be a good way to introduce a skittish child to chickens. An adult can easily close the hatch if the child gets scared — a much more manageable scenario than bringing a youngster into the chaos of a pen full of chickens.

Chickens have a strong culture of follow-the-leader. Sometimes you have to be that leader.

Hens, even the most cooperative, may need a little encouragement to start laying in the nest box, no matter how well it is designed. Persuade them by parking something egglike in the box (a plastic Easter egg, a golf ball, or some such). This will tell the hens that some other, smarter hen thinks your nest box is a safe place for laying eggs, and they’ll want to lay there, too. Chickens have a strong culture of follow-the-leader. Sometimes you have to be that leader.

Fake eggs will help “prime the pump.” To a chicken this looks like a good place to lay eggs.

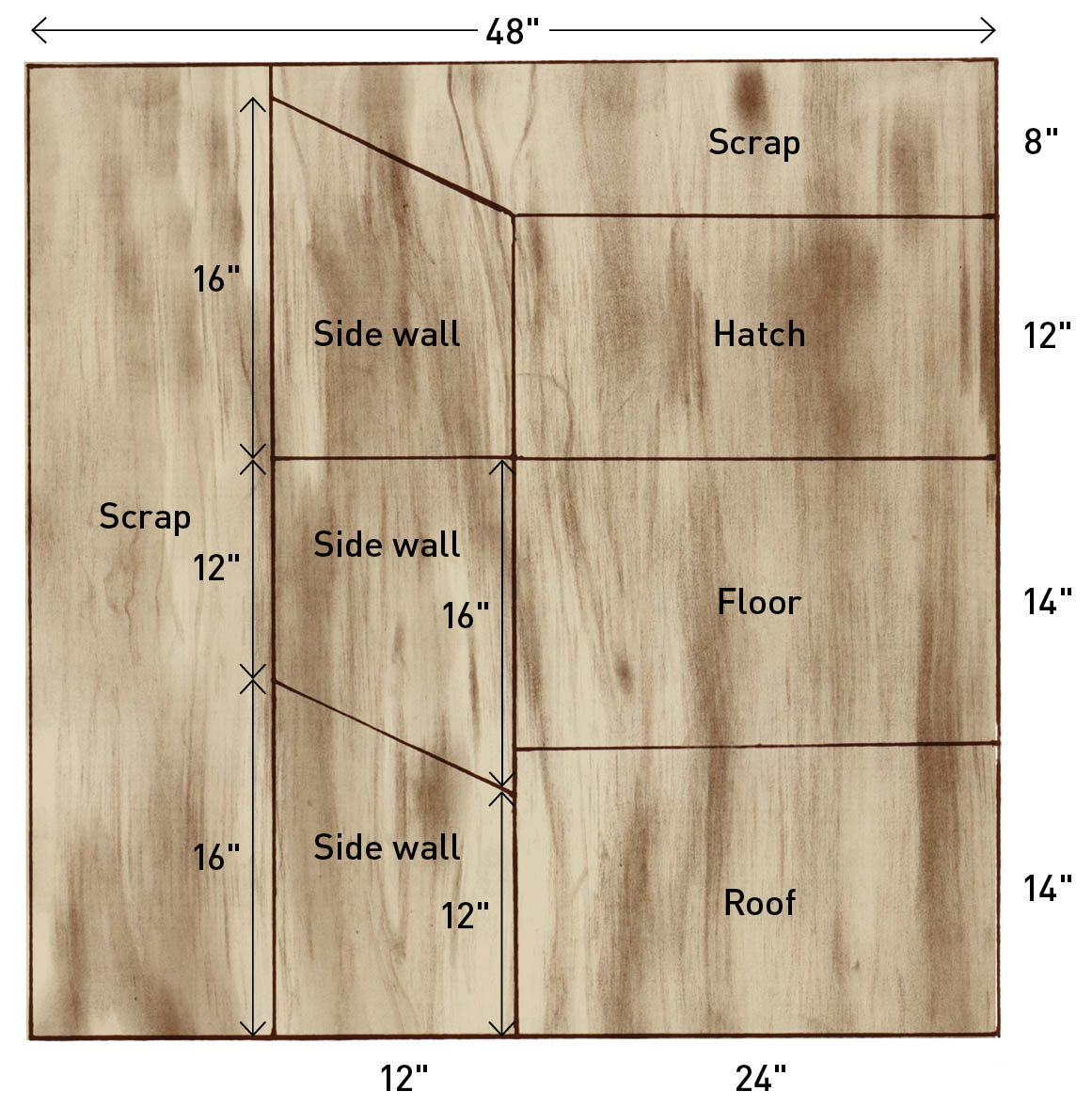

Our nest box is built of plywood that is 3⁄4 inch thick. You can use thicker wood, such as 2 × 4s, but I wouldn’t go thinner than 3⁄4 inch. You need that much thickness to minimize twisting as the wood dries, and to allow you to set a screw securely into the edge of each piece.

Make your cuts with a circular saw if you want to be fast, a table saw if you want to be accurate, a jigsaw if you want to be quiet, or a handsaw if you want to get strong.

A jigsaw is a non-carpenter’s best choice for a safe wood-cutting tool.

Screws will hold things together better than nails. Nails can pull out due to the parts they hold twisting, or from the shrinking and swelling of damp wood. But screws will hold their place because the threads are deeply embedded. And if you need to move the coop or want to enhance the nest box, screws will let you take it apart without butchering it.

You will use a pencil to mark where the screw will go through the first piece of wood, then predrill a hole that’s a tad wider than the threads of the screw (see steps 3 to 5). The screw should slide easily through the first piece of wood and bite solidly into the second piece.

Since the nest box protrudes from the wall of the coop, it will need its own waterproof roof. I used a piece of shiny red scrap metal, but other roofing options will work too: asphalt shingles, cedar shingles, old license plates, flattened number 10 cans, a miniature “green roof,” and so on. Think of the nest-box roof as small-scale but highly visible opportunity to dress up the coop and give it some charm and personality. If the roofing material on the main roof is attractive, there’s no reason not to use the same thing on the nest-box roof.

A bright-colored roof draws attention to an exterior nest box.

The hatch for our nest box has hinges at the bottom and latches on the sides. You could use gate hinges from the hardware store; choose ones that are made for outdoor use and won’t get rusty. Make sure the screws aren’t so long that they poke inside the box.

When deciding on the latches for the external nest box on our coop, I tried to answer the henkeeper’s eternal question: “Are these latches going to be safe enough?” That can also be translated as “What will my wife do to me if critters get her chickens?”

I checked the various chicken chat rooms online and found that a lot of people worried about raccoons getting into their coop. Some had lost so many hens that they were using combination locks to secure the doors. (I guess having that black mask doesn’t qualify a raccoon as a safecracker.)

I think carabiners are tricky enough to keep raccoons out. I put a store-bought metal hasp and carabiner on each end of our nest box door to keep it secure and snug enough to minimize drafts.

A hasp with a carabiner demands two steps to open: squeezing the carabiner and opening the hasp. That will keep raccoons from breaking into your nest box.

How to Make It

A helper will be handy when you build this nest box.

What You Need

What to Do

Prepare the plywood pieces.

Cut the pieces.

Assemble the floor, walls, and roof.

Note: The front edges of the walls meet the front edge of the floor. Double-check the drawingbefore marking and drilling the roof and floor.

Note: The back edges of the walls meet the back edge of the roof.

Attach the hinges.

Attach the latches.

Attach the pivoting support arm.

Mount the nest box.

Attach the nest box to the coop.

Use a drill and jigsaw to cut out an opening that’s 24" wide and approximately 12" high, that will put the nest box floor at approximately 18"–36" above ground.

Put the nest box against the opening. Slide the projecting flange of its floor in over the floor of the coop. Have a helper hold the box in place while you proceed through step 14.

Prepare roofing to fit on the plywood roof.

Install asphalt roofing.

Henkeepers I’ve Known

Suvir Saran grew up in New Delhi, which, he says, is “bigger than New York City in pop and hustle.” As a child, he wanted to keep chickens, but his mother wouldn’t let him. She said there was nowhere in their city home for them to free-range. Instead, he would pick up injured birds and nurse them back to health at home. Within a week, many of them would heal and be returned to the wild. He didn’t know how to plaster their broken wings, but he used gauze and Scotch tape to put their limbs back in order. He fed them milk, grains, and packaged electrolytes. A chef taught him how to disinfect and bathe the birds in a solution of turmeric.

Michelin-star chef Suvir Saran holds one of his Polish chickens in the door to his coop.

Since coming to America in 1993, Suvir Saran has written three cookbooks and was the founding chef of the only Indian restaurant in the United States with a Michelin star, Devi in Manhattan. His lifelong desire to take care of chickens and other animals prepared him for taking care of friends, diners, and his American Masala Farm, near the Hudson River four hours north of New York City.

When he and his partner, Charlie Burd, bought the 70-acre farm in 2006, Suvir was finally able to realize his desire to keep chickens. He says that while most people keep chickens for practical purposes, he loves them for “idealistic reasons”: their plumage, their cautious curiosity, the way the chicks follow the mother hen.

Suvir and Charlie keep approximately 30 heritage breeds from the Livestock Conservancy watch list. The first ones were bought through McMurray’s hatchery, but now Suvir buys them on EggBid.net, sort of an eBay for chickens. People bid against each other for rare breeds.

The farm’s chicken population has ranged from 90 to 120 birds. Since these are heritage breeds, rather than hens bred for production, the flock may lay at most 40 eggs a day. “They are lazy birds, not the best producers,” Suvir says. But he also claims they are “great performers and have great personalities,” and help keep him sane and happy. He has named a few, such as a Crèvecoeur hen called Tina Turner and a Polish hen named Celine Dion.

If he had to choose a favorite breed, however, it might be the rare Penedesencas who, unlike most hens with white ear lobes, don’t lay white eggs. When the pullets are young, their eggs may be nearly black. For Suvir they lay “the deepest dark chocolate eggs.” A friend gave him one and after he saw the eggs he had to order more.

Belgian d’Uccles, also favorites, are affectionate and love to be with humans. “They could very well be housepets,” he says.

Suvir hasn’t had much trouble with diseases in his flock, but living in the country, predators are an ongoing threat: coyotes, foxes, fishers (similar to martens), bobcats, and minks. Once an apple tree fell and disabled the electric fence long enough for coyotes to get in and kill a baby goat. Suvir and Charlie repaired the fence but realized they had inadvertently trapped a couple of coyotes on the farm. They were both generally opposed to firearms, but Charlie, who grew up in West Virginia, procured a rifle and dispatched the coyotes with a few rounds.

They lost 60 birds to a mink one night when a caretaker left a tiny coop door open. After that they picked up some llamas and alpacas, which have been wonderful guard animals. They now have 25 of these fleece-bearing Andean animals.

The chicken eggs, along with the alpaca fleece, provide a small side business for Suvir and Charlie. Local restaurants pay $3.50 a dozen and the public pays $5 a dozen for the eggs. Given the cost of organic feed, Suvir says the income doesn’t fully cover the time or effort.

Suvir loves the plumage of roosters, but he hasn’t been able to keep them for long. To minimize their pecking on hens, his roosters live outside the coop and eventually get taken by critters. The guinea hens managed to kill one rooster, so he keeps them separate now. One rooster was smart enough to cohabit with the alpacas and roost safely in their barn. Even he lasted only three years.

When doors are closed the coop is quite secure and has some appealing features. For summer ventilation, the ceiling is even higher than that in the farmhouse, and the gables have wire covers for air flow. Windows also have wire covers for summer ventilation and can be closed like storm windows in long winters so hens stay warm from their body heat. There is a frostproof water spigot in the center of the coop so waterers can be easily refilled year-round. A couple of big skylights in the roof flood the coop with sunlight as a disinfectant and an encouragement to lay.

A people door opens into the center space of the coop, from which the owners can gather eggs from nesting boxes without disturbing the hens. One area is fenced as a nursery for newly hatched chicks. There, they are safe from bullying and Suvir and Charlie can handle and pet them, and, Suvir says, this “allows us to spoil them a bit.”

When the chicks are nearly full size, they get access to the rest of the coop. In his cookbook Masala Farm, Suvir says, “We introduce them during the night as that is when the birds are at their most docile. You see, the minute the sun sets, chickens pretend that the world has ended — they just drop! We open the coop door, bring the younger birds in, and leave them on a perch. In the morning, they all wake up together and think they have lived together their whole lives. It’s a beautiful thing.”

The coop has three pop-up doors that let Suvir and Charlie control which fenced part of the farm the hens can access. Between growing seasons, the hens are allowed access to the vegetable garden to feast on its remains and till and fertilize the beds. During the growing season, the hens have access to the larger farm with its pasture, ponds, and 50 bushes producing blueberries, strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, gooseberries, and elderberries.

The hens aren’t limited to layer feed and foraging. Because they host frequent holiday events and gatherings, Suvir says, “With a revolving door of visitors to the farm, there is never a dearth of kitchen scraps. They especially love citrus and chilies. Hot peppers are a favorite. In the winter, we make it a point to make extra soups and stews, vegetarian of course, that they get piping hot, and they savor them with glee.”

Suvir would love to expand his flock to include a collection of bantam hens. For that he plans to build a mini-coop to keep them safe at night. He says, “The few bantams we have had, have been the most darling birds, and with the sweetest and most friendly demeanor. I am smitten by them.”

Suvir’s spiced twist on classic deviled eggs. Even if the eggs are fresh, refrigerate them for seven days before boiling. Aging allows the inner membrane between the shell and the white to loosen, making the cooked eggs easier to peel. From Masala Farm: Stories and Recipes from an Uncommon Life in the Country

Ingredients

Instructions