Starting location: Sloane Street.

Nearest tube station: Sloane Square or Knightsbridge.

Nearest bus stop: Pont Street (19 or 22 bus).

Length: 2.25 miles walking all the way; 1.5 miles taking the bus between Sloane Street and Hyde Park Corner.

Opening hours:

• APSLEY HOUSE: www.english-heritage.org.uk. Opening times vary according to season.

• KENSINGTON PALACE: www.hrp.org.uk/KensingtonPalace. Open daily from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Last admission 4 p.m.

A Hans Town bollard, which served to protect pedestrians from traffic on corners.

Jane’s brother Henry and his wife Eliza moved to 64 Sloane Street in 1809. Knightsbridge was still a separate village – on 18 April 1811 Jane wrote, ‘If the Weather permits, Eliza & I walk into London this morng.’

Sloane Street was part of the Hans Town development, built up from 1771. With its well-paved roads and patrolling night watchmen, it attracted prosperous professionals like Henry who was a banker with offices in Covent Garden.

No. 64 had three stories with an attic floor, but in 1897 another floor was added and the house refaced. Despite appearances, Henry’s house is still there, enclosed in this later shell.

During that first stay in April 1811 Jane was correcting proofs of Sense and Sensibility. ‘No indeed, I am never too busy to think of S&S. I can no more forget it, than a mother can forget her sucking child,’ she wrote to Cassandra. But it was not all work – Eliza gave an entertainment mentioned in the Morning Post of 25 April, which must have been very gratifying, even if the newspaper spelled her name wrong: ‘Mrs H Austin had a musical party at her house in Sloane-street.’

No. 64 Sloane Street.

No. 23 Hans Place. Somewhere inside is the ghost of the house Jane knew.

It was held on the first floor in the octagonal rear salon and the front drawing room. Jane told Cassandra that she spent most of the time talking to friends in ‘…the connecting Passage, which was comparatively cool, & gave us all the advantage of the Music at a pleasant distance, as well as that of the first view of every new comer.’ There were glee singers, a harpist and floral decorations.

Between 22 April and 1 May 1813 Jane stayed here to support Henry through Eliza’s final illness: she died on 25 April. On 20 May Jane, who was again with her newly widowed brother, wrote that she was very snug with the front drawing room all to herself.

She enjoyed the little luxuries that Henry could afford. ‘The Driving about, the Carriage being open, was very pleasant. I liked my solitary elegance very much, & was ready to laugh all the time, at my being where I was – I could not but feel that I had naturally small right to be parading about London in a Barouche.’

After Eliza’s death Henry moved away but eventually returned to live in Hans Place, just around the corner.

Turn into Hans Street and look at the back of No. 64. There you can see the three external walls of the octagonal room that was the scene of the musical party.

At the end of the street turn left into Hans Place and continue round to No. 23. Jane stayed here for the first time on 22 August 1814. She arrived in London by stagecoach and was then collected by Henry, in ‘the Luxury of a nice large cool dirty Hackney Coach.’

View of Piccadilly from Hyde Park Corner Turnpike in 1810. The first house on the left became Apsley House. Carriages are coming out of Hyde Park beside it; Green Park is on the right.

She declared, ‘It is a delightful Place – more than answers my expectation… I find more space & comfort in the rooms than I had supposed, & the Garden is quite a Love.’ They could even talk across the garden fence to the family of Mr Tilson, Henry’s partner at the bank, who lived at No. 26.

Hyde Park Turnpike in 1792 looking towards Piccadilly with Green Park on the right.

‘I am in the front Attic, which is the Bedchamber to be preferred.’ This was below the present top floor and over the original front door, which was at the side where the Blue Plaque is located.

Special traffic lights at Hyde Park Corner, both for carriage horses from the Royal Mews at Buckingham Palace and recreational riders.

In 1884 the house was encased within a brick shell and the exterior considerably altered. The plaque refers to ‘a house on this site’ but, like Sloane Street, the original remains, encased inside its new skin.

Henry’s study was at the back, with a balcony and steps down into the garden, which has now been lost under Pont Street. Jane did much of her letter writing and proof reading in this room.

It was at Hans Place that the transfer of her business to publisher John Murray was negotiated by Henry during the autumn of 1815. Henry became seriously ill in October and he was moved down from the bedroom floor to a back room where Jane kept him company while she wrote.

Perhaps the illness was caused by the stress of his failing business. The Alton branch of his bank collapsed in late 1815; all the other branches followed it in March 1816 and Henry was declared bankrupt. That year he became a country clergyman and Jane’s visits to London ceased.

Tattersall’s auction ring: the knowledgeable crowd place their bids.

Dashing amongst the Pinks in Rotten Row, 1821. Ladies ride side saddle; smart army officers and young swells canter amongst the carriages.

Return to Sloane Street where you can either follow Jane’s example and ‘walk into London’ through Knightsbridge (three quarters of a mile) or catch a bus to Hyde Park Corner if you prefer to save your energy for the later walk in the park.

The dominating landmark at Hyde Park Corner is Apsley House, known as Number One London because it was the first house on the Hyde Park turnpike after the toll gate. Built by Robert Adam in the 1770s, it was purchased by the Duke of Wellington for his London residence when he began his political career. When Jane knew this area it was simply the first of a terrace of smart town dwellings that were demolished when the house was redeveloped in its present form.

Apsley House is well worth visiting. The beautifully preserved interior contains Wellington’s collection of art works, the lavish gifts presented to him by grateful rulers, and even a nude statue of Napoleon.

Standing outside, look diagonally across to the Lanesborough Hotel. Until 1825 Hyde Park turnpike gates stood just about where Grosvenor Place meets Knightsbridge.

Jane’s letter home on 25 April 1811 blames an incident at the gates for giving her sister-in-law Eliza a chest cold. ‘The Horses actually gibbed on this side of Hyde Park Gate – a load of fresh gravel made it a formidable Hill to them, & they refused the collar; I believe there was a sore shoulder to irritate. Eliza was frightened, & we got out & were detained in the Eveng air several minutes.’

Tattersall’s auction ring was situated just behind the site of the Lanesborough between 1766 and 1865. It became a sort of club where noblemen, gentlemen, grooms and jockeys could be found mingling and conversing, united by their love of sport.

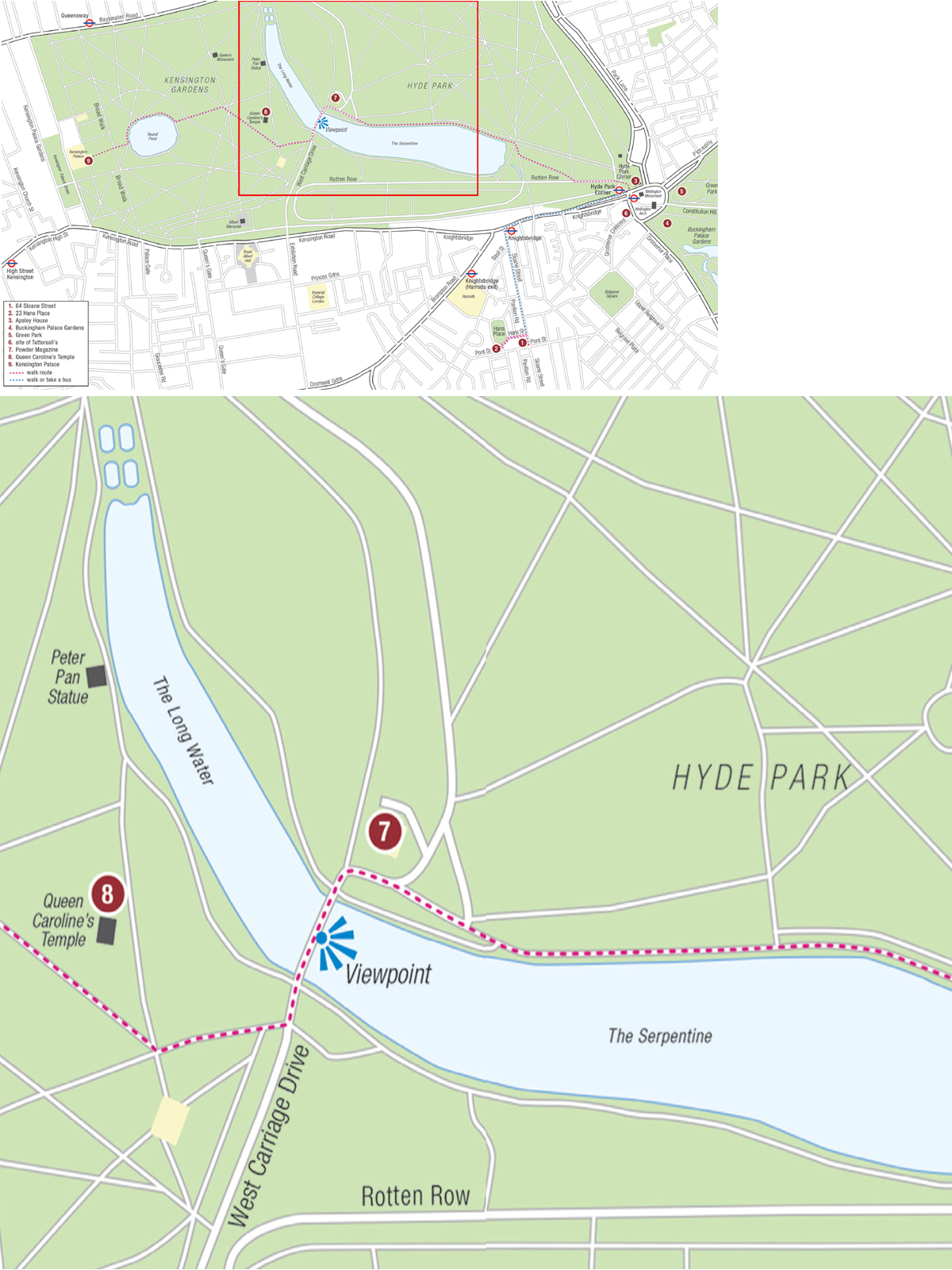

Go through the gate into Hyde Park, which formed the western edge of London during the early nineteenth century. On your left is the sandy track of Rotten Row: take the right-hand footpath alongside it.

During the Season, Society paraded here every afternoon. It was considered essential to see and to be seen in your most fashionable clothes, riding your finest horse or driving the most expensive carriage you could afford.

If Jane wished to view Society on display, this was the place to be, as The Picture of London advises:

We recommend [the stranger] to pause at some spot…from which his eye can command the entire picture of carriages, horsemen, and foot passengers, in the park, all eager to push forward in various directions, and the more composed picture of the company sauntering in the gardens.

The Queen’s Temple in Kensington Palace Gardens was built as a summerhouse for Queen Caroline in c. 1734. Some of the graffiti inside dates to 1821 when the whole of the Gardens was thrown open to the public on a daily basis.

In early March 1814, Fanny and Jane drove in Hyde Park and Jane was much entertained, although somewhat put out not to be seen by a single acquaintance.

Before you reach the Serpentine, cut through the gardens to follow the road along the northern bank and over the bridge.

The Westbourne, one of London’s ‘lost’ rivers, flows down from Hampstead and was dammed in 1730 to form the Serpentine. In 1816 Harriet Shelley, wife of the poet, drowned herself here.

On the right, as the road turns to cross the bridge, is a building mentioned in The Picture of London as:

... a powder magazine and a guardroom, both of brick, the sight of which if they must be there for the sake of any convenience, ought to be obscured by planting ... Hyde Park is used for the field days of the horse and foot guards … and for some martial reviews; which however is not mentioned as an advantage to the beauty of the place, as these exercises destroy the verdure of the park.

Kensington Gardens Walking Dresses from La Belle Assemblée, July 1808.

One imagines that Lydia Bennett, with her penchant for men in scarlet coats, would have found this a most attractive sight.

Once over the bridge we are in Kensington Gardens, once the private park belonging to the palace. The lake on the right is The Long Water.

Make your way across the Gardens to the Round Pond and beyond it to the Broad Walk, a very popular promenade in front of the palace, as described in The Picture of London:

One of the most delightful scenes belonging to this great metropolis, and that which, perhaps, most displays its opulence and splendour, is formed by the company in Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens, in fine weather, chiefly on Sundays in winter and spring … Numbers of people of fashion, mingled with a great multitude of well-dressed persons of various ranks, crowd the walk for many hours together … No servant in livery, nor women with pattens, nor persons carrying bundles, are admitted into the gardens.

The unicorn of Scotland on the southern gates of Kensington Palace. The unicorn joined the English lion as a supporter of the royal coat of arms when James VI of Scotland became James I of England in 1603.

In April 1811 Jane wrote, ‘I had a pleasant walk in Kensington Gs on Sunday with Henry, Mr Smith & Mr Tilson – everything was fresh & beautiful.’

Perhaps it was this excursion she had in mind when, in Sense and Sensibility, Mrs Jennings and Elinor meet Miss Steele there.

[It was] so beautiful a Sunday as to draw many to Kensington Gardens, though it was only the second week in March. Mrs Jennings and Elinor were of the number; but Marianne, who knew that the Willoughbys were again in town, and had a constant dread of meeting them, chose rather to stay at home, than venture into so public a place.

In Jane’s day Kensington Palace was home to various members of the royal family, including Princess Caroline, the estranged wife of the Prince Regent. He stopped their daughter, Princess Charlotte, visiting her here when he discovered she had frequently been left unchaperoned with a gentleman.

There is a collection of lavish court dress and the royal staterooms are open to the public, including the bedchamber where Princess Victoria was told she had become queen – the day the Georgian era ended.