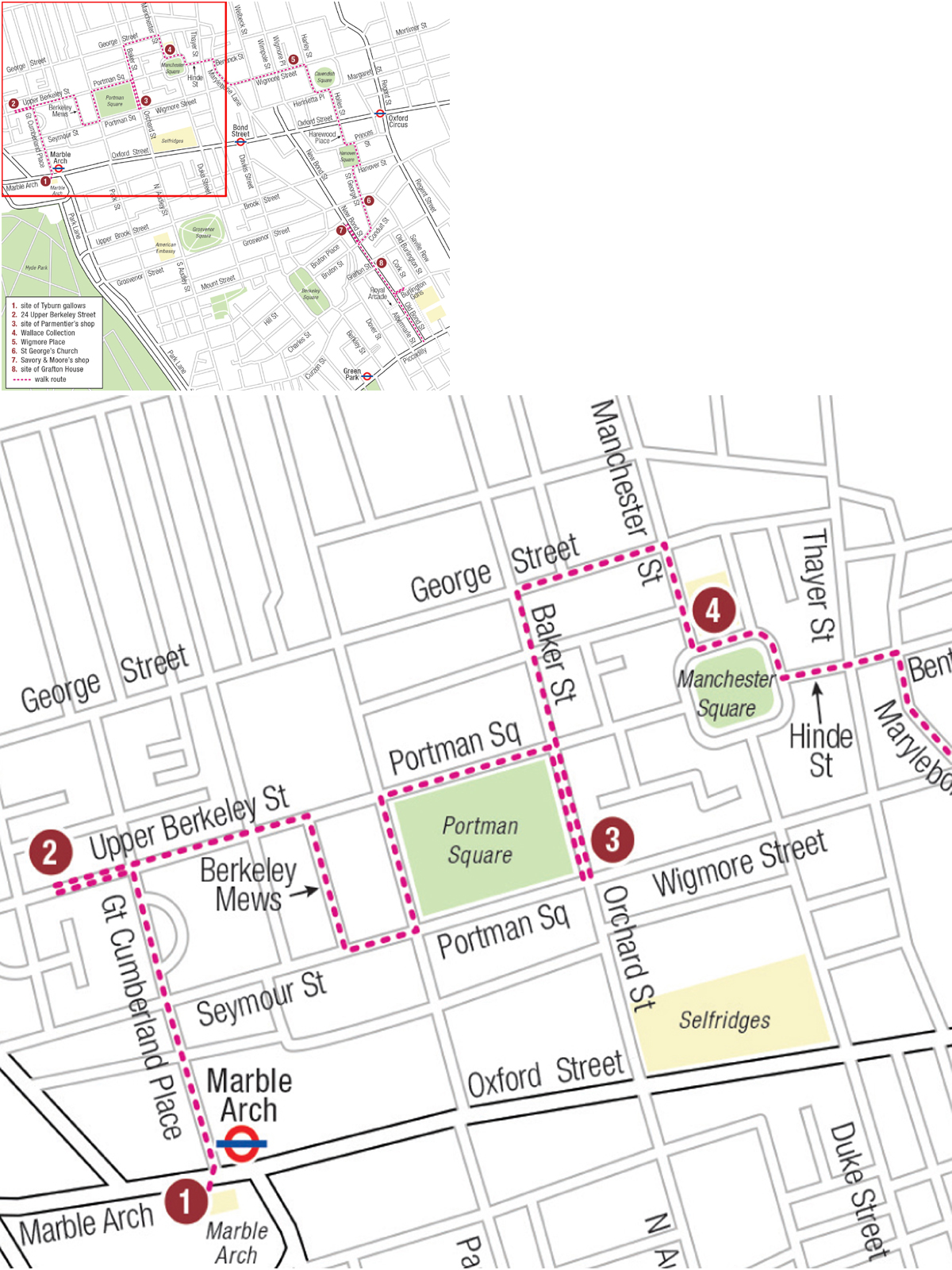

Starting Location: Marble Arch.

Nearest tube station: Marble Arch.

Length: 2.25 miles.

Opening hours:

• WALLACE COLLECTION: www.wallacecollection.org. Open daily (except 24–26 December), from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Marble Arch is close to the site of Tyburn gallows, but by the time Jane Austen was born the procession of the condemned through the streets amidst jeering, cheering crowds was thought distasteful – and, perhaps more influentially, it disturbed the peace of the fashionable residents of the new developments north of Oxford Street. Public executions were moved to Newgate prison in 1783.

Walk up Great Cumberland Place, the location of the American Legation chancery in 1805, and turn left into Upper Berkeley Street. The elegant streets and squares that were developed in the Marylebone district north of Oxford Street in the late eighteenth century attracted gentry, nobility and the higher echelons of the professions. There was a considerable variety in the size of houses available, from grand mansions to modest dwellings like the one where Henry and Eliza Austen lived between 1801 and 1804.

The district also retained some rough edges including a huge cattle yard just off the Edgware Road. The beasts must have been audible, and, when the wind was right, the smell would have wafted over the smart streets.

The Austens lived close to this nuisance in some style at No. 24 on the north side of the street, employing a French cook and keeping a carriage.

Tyburn Turnpike looking eastwards along Oxford Street in 1813. The transformation of Oxford Street into a fashionable shopping street began in the middle of the eighteenth century. No trace of the Georgian era survives except for one pillar at the entrance to Stratford Place.

The house is now a small hotel. There is no record that Jane visited No. 24 but Cassandra stayed here during February 1801 and Jane wrote to her, ‘I hope you will see everything worthy notice, from the Opera House to Henry’s office in Cleveland Court.’

Return to cross Great Cumberland Place and continue along Upper Berkeley Street. Turn right into Berkeley Mews. London was full of mews to provide stabling for the thousands of horses and carriages – perhaps Henry kept his here.

The Mews leads to Seymour Street where we turn left onto Portman Square, begun in 1761. ‘The residence of luxurious opulence,’ according to Priscilla Wakefield, this was one of the most fashionable addresses in London.

Lord Castlereagh lived here at one time and he was closely associated with Lord Liverpool’s repressive government. Shelley wrote of him in The Mask of Anarchy:

I met Murder in the way –

He had a mask like Castlereagh –

Henry Austen’s house at 24 Upper Berkeley Street. It has lost some of its Georgian detail but the house next door shows how the windows and fanlight would have looked.

Following the Peterloo Massacre in 1819 a furious mob attacked his house and smashed the windows.

Walk around the square clockwise to admire the remaining traces of its splendour until you reach Orchard Street. This is where Jane’s aunt, Mrs Hancock, and her cousin Eliza were living in 1788 and she dined with them here in August of that year during her first recorded visit to London.

Wigmore Street leads out of the square at this point, but originally this section was Edwards Street, the location of Parmentier’s, confectioner to high Society and royalty. Given her liking for everything fashionable, and with her French taste, Henry Austen’s wife Eliza may well have ordered from them when she lived nearby. Here were sold preserves, jellies, jams, fruit pastes, fruits in French brandy, comfits, lozenges, macaroons and rout cakes, as well as ices and creams.

A bill from Parmentier’s to a gentleman living in Harley Street, April 1812. A bottle each of orange and lemon ‘syrop’ and a dozen rout cakes totals eighteen shillings.

Go back along the eastern side of the square to Baker Street. In Mansfield Park this was the London address of the Andersons where Tom Bertram met Miss Anderson, who later embarrassed him with her forward behaviour.

As you walk up Baker Street it is difficult to believe that it was called ‘perhaps the handsomest street in London,’ in The Picture of London.

Turn right into George Street, the location of The Hindoostanee Coffee House, the first Indian restaurant in London, opened by Sake Dean Mahomed in 1810. Despite offering food that was advertised as authentically Indian, and giving gentlemen the opportunity to smoke a hookah, it failed to become popular and closed after a year.

Manchester Square in 1813, showing Manchester House, now home to the Wallace Collection.

George Street leads to Manchester Street, the temporary address of the Churchills in Emma. In 1814 the prophetess Joanna Southcott died at No. 38. Followers watched her grave in St John’s Wood churchyard for years in the hope of her promised resurrection.

Turn right to Manchester Square, the home of the Wallace Collection, a superb gallery of art, furniture, paintings and armour. It was originally Manchester House which was, according to The Picture of London, ‘one of the best in London’.

Hinde Street leads from the square to ancient Marylebone Lane, winding through Marylebone village. Ahead is Bentinck Street where Jane visited her friends the Cookes in April 1811.

Turn right down Marylebone Lane, left into Wigmore Street and along to cross Wimpole Street. This was the scene of scandal in Mansfield Park when Maria Rushworth, who lived here with her dull husband, ran off with Henry Crawford: ‘… it was with infinite concern the newspaper had to announce to the world, a matrimonial fracas in the family of Mr R. of Wimpole Street.’

Another scandalous marriage began in Wigmore Street in 1791 when Sir William and Lady Hamilton set up their first home together. She, of course, became Nelson’s mistress. Ironically, in the same year, Captain and Mrs Horatio Nelson were living just a short distance away in Cavendish Square.

The north side of Cavendish Square in 1813. The chaise with its postilions is drawn up in front of a pair of houses that can still be seen today. This is a typical colour for a post chaise – they were known as ‘yellow bounders’.

At the corner of Wigmore Place is No. 10 where Frederica in Lady Susan attends boarding school. On the other side of Wigmore Street, No. 11 was the location of Christian and Sons, drapers. In May 1813 Jane mentions visiting the shop to buy dimity, a figured cotton cloth.

Walk on to reach the corner of Harley Street. In Sense and Sensibility the John Dashwoods had taken a very good house for the season in Harley Street and Mrs Dennison visits when Elinor and Marianne are calling on them. To Fanny’s annoyance she invites the sisters to a musical evening, which obliges Fanny to send her carriage to collect them, a gesture which she feels gives them a most unjustified status.

Harley Street, today synonymous with doctors, had only a few of them in Jane’s day. It did, however, appear to attract the military. The Duchess of Wellington lived at No. 11 while her husband was serving in the Peninsula, Admiral Lord Keith lived at No. 89 and Admiral Hood at No. 16. Naval widows Lady Nelson and Lady Rodney also resided here.

The building occupied by Coutts Bank on the corner of Cavendish Square was lived in for many years by Princess Amelia, the unmarried daughter of George II. A little further along on the same side of the square is a pair of handsome Palladian frontages flanking Dean’s Mews.

Statue in Hanover Square of William Pitt the Younger. First appointed at the age of twenty-four, Pitt was the youngest-ever Prime Minister. He died in 1806 having been in office throughout most of the wars with France.

When Henry Mayhew was writing London Labour and the London Poor in the mid-nineteenth century he quoted ‘Billy’ who was, for many years, a crossing sweeper in the area. Billy had seen Queen Caroline, the estranged wife of George IV, pass through the square after her trial. ‘They took the horses out of her carriage and pulled her along. She kept a-chucking money out of the carriage, and I went and scrambled for it, and I got five-and-twenty shillin’.’

Leave Cavendish Square by Holles Street, cross Oxford Street and follow Harewood Place to Hanover Square. In Sense and Sensibility Mrs Palmer, on hearing that the Dashwood sisters are not coming to Town, protests that she could have found them, ‘the nicest house in the world for you, next door to ours, in Hanover Square.’

St George’s, Hanover Square. View along St George Street from the south in 1812.

St George’s, Hanover Square was a fashionable choice for weddings. In Mansfield Park Mary Crawford hints at Fanny and Henry getting married here.

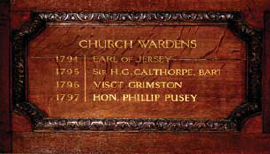

The interior looks much as it did at that time, although the box pews were changed in the 1870s. Handel was a regular worshipper and the Earl of Jersey, whose wife was one of the Patronesses of Almack’s, was a churchwarden in 1794. Lady Jersey was nicknamed ‘Silence’ because of her never-ending chatter – perhaps she was quieter during services.

At the bottom of the road is Conduit Street where Sir John and Lady Middleton lived in Sense and Sensibility. The Misses Steele stay with them and the Dashwood sisters spend more time there than they would like.

It was also the location of Limmer’s Hotel, ‘the most dirty hotel in London,’ according to Captain Gronow. Despite this, ‘in the gloomy comfortless coffee-room might be seen many members of the rich squirearchy, who visited London during the sporting season.’

Turn right to reach New Bond Street. Most early buildings have been swept away but it remains the exclusive shopping street that it was when Jane knew it well. Priscilla Wakefield tells us, ‘Bond-street is the grand mart for fashionable items of dress, and is consequently the resort of ladies of the ton, who assemble there in splendid carriages; whilst idle beaux, distinguished by the appellation of Loungers come to gaze at them, and, in their turn to attract attention.’

Two until five was the time for being seen during the Season and Sir Walter Scott, Byron, Brummell and the Prince Regent were frequent ‘loungers’.

One of the plaques in St George’s listing the churchwardens, including the Earl of Jersey in 1794.

Jane knew it well and placed her characters here with confidence. In Sense and Sensibility Marianne, miserable over Willoughby, is a poor companion on a shopping trip:

In Bond-street especially, where much of their business lay, her eyes were in constant inquiry; and in whatever shop the party were engaged, her mind was equally abstracted… Restless and dissatisfied every where, her sister could never obtain her opinion of any article of purchase…and [she] could with difficulty govern her vexation at the tediousness of Mrs Palmer, whose eye was caught by every thing pretty, expensive, or new; who was wild to buy all, could determine on none, and dawdled away her time in rapture and indecision.

A fashionable young gentleman of 1813 wearing buckskin breeches.

Willoughby is lodging in Bond Street when he writes to Marianne, protesting that he had never intended to court her as his affections were already engaged elsewhere.

The street was full of hotels, lodgings and eating places as well as shops. Steven’s and Long’s hotels were both favourites of the ton, as members of fashionable Society were known. Byron and Scott patronised Long’s dining room and Steven’s attracted aristocratic army officers. They were so exclusive that if a stranger wished to dine at Steven’s the staff would inform him that there were no tables, whether there were or not.

In the evening, bands of Savoyard Pandeans with their panpipes would gather in the porches and entertain the gentlemen inside and the less exalted crowd outside.

A band of Pandean minstrels showing the panpipes that gave them their name. This troupe is performing at Vauxhall pleasure gardens in 1806.

Turn right, and almost immediately opposite is The Fine Arts Society. Lord Camelford, a noted eccentric, lived over a grocer’s shop on this site, and provoked a riot when London was illuminated to celebrate the short-lived peace in 1801. He refused to allow his landlord to light up the windows as the mob demanded and the house was stormed. His lordship threw one man down the stairs before emerging with a cudgel to fend off the attackers.

In 1797 Lord Nelson lived next door on the site of No. 147. He was very ill at the time, following the loss of his right arm at the second battle of Cape St Vincent, and received devoted nursing from Lady Nelson.

The shop front of No. 143 is the original belonging to the chemists Savory and Moore, founded in 1794. Thomas Field Savory was a talented chemist with friends in high places. Wellington and Lady Hamilton were customers and the Duke of Sussex, brother of George IV, often dined here as his guest. In 1815 Savory acquired the patent for the internationally popular laxative Seidlitz powders, which made his fortune.

Turn to walk down to the corner of New Bond Street and Grafton Street. This was the location of Grafton House, home of high-class drapers Wilding and Kent. On 17 April 1811 Jane and Manon, Eliza Austen’s maidservant, ‘… took our walk to Grafton House, & I have a good deal to say on that subject. I am sorry to tell you that I am getting very extravagant & spending all my Money; & what is worse for you, I have been spending yours too …’, she told Cassandra.

Plaque to Nelson on 147 New Bond Street.

Savory and Moore’s original shop front.

Wilding and Kent’s was obviously a busy shop. In November 1815 Jane complains of ‘the miseries’ of shopping there and most of her references to it mention an early start and long waits to be served – not that this stopped her going there frequently.

The Clarendon Hotel, Bond Street, close to Wilding and Kent’s shop. The officer is accompanied by a smartly trimmed poodle.

By the time we reach Burlington Gardens we are in Old Bond Street. Turn into Burlington Gardens to look up Cork Street, on the left. Jane stayed here in August 1796, probably in a hotel with other family members, and wrote jokingly to Cassandra, ‘Here I am once more in this scene of Dissipation & vice, & I begin already to find my Morals corrupted.’

Returning to Old Bond Street, Trufitt and Hill had been at No. 23 since 1805 when Francis Trufitt set up as ‘court hair and head dresser’. They were wigmakers to George IV and are now located in St James’s Street where we pass their shop during Walk 4.

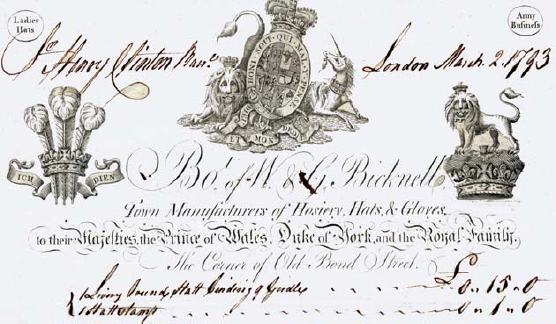

Shops with a Royal Warrant were sure to publicise the fact. This account was sent out by ‘W. & G. Bicknell. Town Manufacturers of Hosiery, Hats & Gloves to their Majesties, the Prince of Wales, Duke of York and the Royal Family. The Corner of Old Bond Street.’ The bill, totalling £7 8s 6d, is for footmen’s livery.

Ladies would not visit a hairdresser’s shop, expecting the coiffeur to call on them. On 15 September 1813 Jane reported that her hairdresser, ‘Mr Hall was very punctual yesterday & curled me out at a great rate. I thought it looked hideous, and longed for a snug cap instead, but my companions silenced me by their admiration. I had only a bit of velvet round my head. I did not catch cold however.’

Gieves the tailors made uniforms for many naval leaders of the Napoleonic wars – Nelson, Hood and Rodney amongst them – while Dollands supplied their telescopes, including the one Nelson used on HMS Victory. Their shops were on the site of the Royal Arcade. Another superior tailor, Weston, was close by.

Jane may have enjoyed Hookham’s library, opposite Stafford Street, one of the most fashionable of the numerous bookshops and lending libraries in the district.

Almost next door was Gentleman John Jackson’s gymnasium where he taught boxing and fencing to the gentlemen of the ton, including the Prince Regent.

Continue down Old Bond Street to reach Piccadilly where our walk ends.