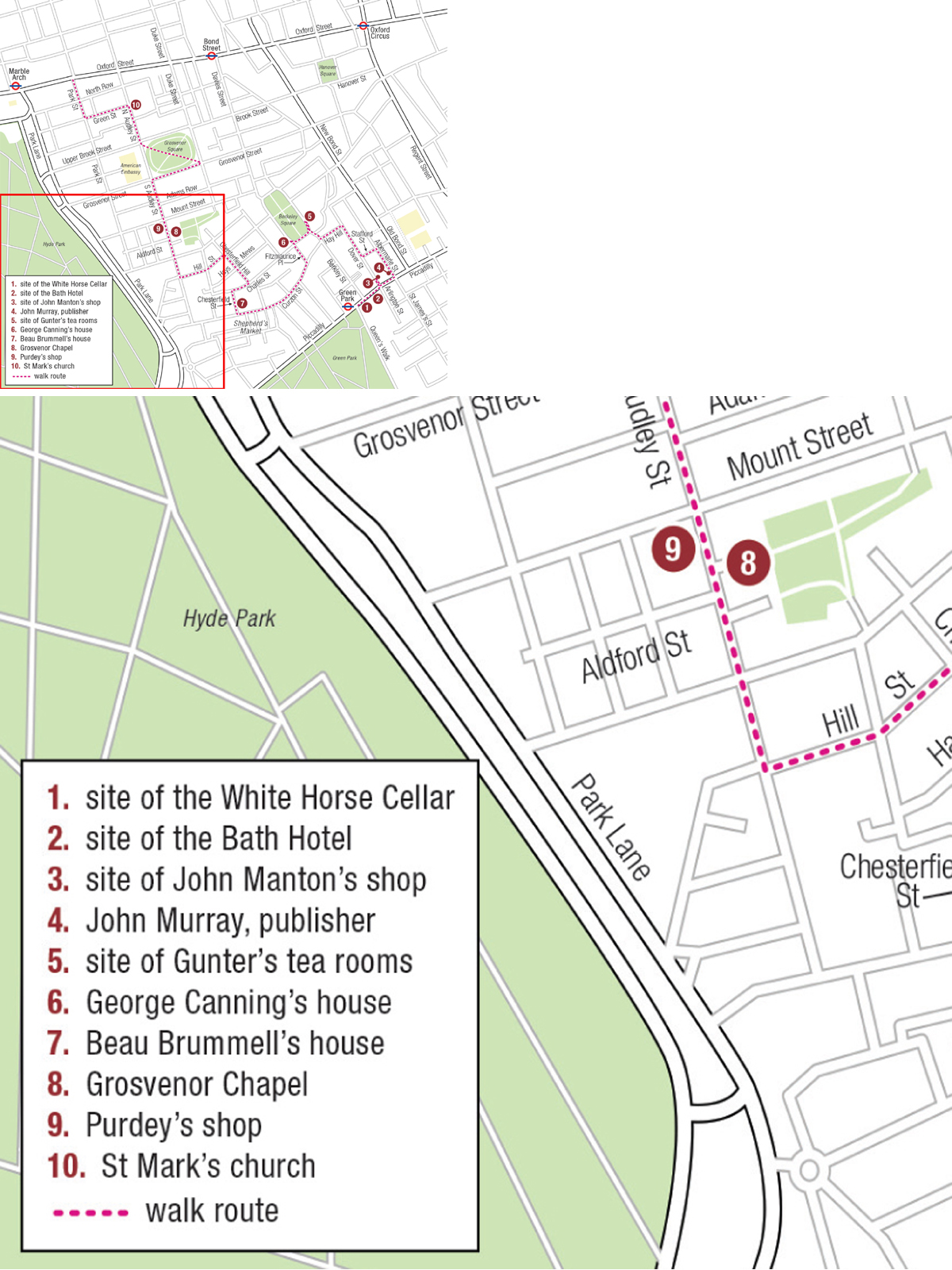

Starting Location: The Ritz Hotel.

Nearest Tube Station: Green Park.

Length: I.75 miles.

The White Horse Cellar, which stood on the site of the Ritz, was a principal boarding point for stagecoaches to the south and west, a three-storied building with a gallery along the top overlooking the yard. Viewing the departure of the stages was a popular amusement for Londoners and it would have been a noisy and crowded spot.

On the western corner of Arlington Street was the Bath Hotel where Jane stayed in June 1808. She was not impressed. ‘At half after seven yesterday morning Henry saw us into our own carriage, and we drove away from the Bath Hotel; which, by the bye, had been found most uncomfortable quarters – very dirty, very noisy, and very ill-provided.’

The sign over the Ritz arcade fronting Piccadilly.

Cross Piccadilly and look up Dover Street. On the right, just after the Clarendon pub, was No. 6, where from 1810 gunsmith John Manton had his shop. This was a popular meeting place for gentlemen, where they could practise their shooting in the special gallery and prove their skill by ‘culping’, or hitting a ‘wafer’ (a paper letter seal) used as a target. His brother, and bitter rival, Joseph, had his shop in Davies Street, which enters the north-west corner of Berkeley Square.

Brass plaque on John Murray’s front door.

Continue along Piccadilly and turn left into Albemarle Street, the home of publisher John Murray, whose premises have been at No. 50 since 1812. He published many of the great names of the era, notably Byron.

Throughout the autumn of 1815 Henry Austen negotiated with Murray on his sister’s behalf. On 21 October he wrote from his sickbed:

The Politeness & Perspicuity of your Letter equally claim my earliest Exertion. Your official opinion of the Merits of Emma, is very valuable & satisfactory. Though I venture to differ occasionally from your Critique, yet I assure you the Quantum of your commendation rather exceeds than falls short of the Author’s expectation & my own. The Terms you offer are so very inferior to what we had expected, that I am apprehensive of having made some great Error in my Arithmetical Calculation … but Documents in my possession appear to prove that the Sum offered by you for the Copyright of Sense & Sensibility, Mansfield Park & Emma, is not equal to the Money which my Sister has actually cleared by one very moderate Edition of Mansfield Park ...

The voice of Jane herself comes across very clearly here, even if it is her brother who signs! Eventually they agreed on a second edition of Mansfield Park and the publication of Emma. Following its dedication to the Prince Regent, Murray brought out an edition of two thousand at twenty-one shillings for the three-volume set. In 1817 he published Northanger Abbey and Persuasion posthumously, but he remaindered the last copies of Jane’s work in 1820.

The visit of the Allied Sovereigns in 1814 for the peace celebrations resulted in a flurry of activity amongst the fashionable modistes. This is a ‘Russian Mantle, Pelisse & Bonnet, Invented & to be had only of Mrs Bell’, appearing in La Belle Assemblée in November 1814. Vast muffs were highly fashionable at the time.

The relationship was generally friendly – Jane borrowed books from Murray for Henry, including John Scott’s A Visit to Paris in 1814 and The Field of Waterloo – but it was definitely a business affair: ‘… he is a Rogue of course, but a civil one’, she told Cassandra.

There were several smart hotels here. Gordon’s, on the corner with Piccadilly, was a favourite of Nelson and Byron but the most famous, Grillon’s, was opposite John Murray’s. Louis XVIII stayed there for two days in 1814 during the premature celebrations of Napoleon’s defeat.

The Edinburgh Annual Register recorded his departure on 23 April:

This morning, about eight o’clock, his most Christian majesty, the Duchess of Angouleme, the Prince de Condé, and the Duke de Bourbon, left London to embark at Dover for France. An immense concourse of people had assembled in Albemarle-street at an early hour. The escort of horse-guards took their station opposite Grillon’s Hotel soon after six.

Berkeley Square and one of its ancient plane trees.

Turn left into Stafford Street to Dover Street and turn right, then left down Hay Hill. Originally this was a farm track to the Tyburn Brook. Even after it was developed it was not always safe – the Prince Regent and some friends were held up here and robbed of the not very princely sum of two shillings and sixpence.

At the foot of the hill we reach Berkeley Street where Elinor and Marianne stay with Mrs Jennings in Sense and Sensibility. Marianne pines for a visit from Willoughby, but when she finally encounters him at a party he snubs her: ‘They departed as soon as the carriage could be found. Scarcely a word was spoken during their return to Berkeley-street. Marianne was in silent agony, too much oppressed even for tears…’.

To the right is Berkeley Square, the location of Gunter’s renowned tea shop at No. 7. We encounter the site almost immediately to find that refreshments of a rather different sort can still be enjoyed in a modern building.

Fashionable young ladies choose their ice creams from the menu in a very elegantly furnished confectioner’s shop.

Gunter’s served exquisite ices and sorbets to eat either in the shop or in one’s carriage under the plane trees – the ones that still shade the square are the originals, planted in 1789.

Berkeley Square in 1813. Two servants in livery stand gossiping outside the houses on the west side.

Mr Gunter maintained an extensive garden in Earl’s Court, in the village of Kensington, which supplied the shop twice daily in season with soft fruits and exotic – and very expensive – pineapples.

In the eighteenth century the south side of the square was taken up by the gardens of Lansdowne House stretching down to Piccadilly. On the west side is a series of mid-eighteenth century houses with fine ironwork.

George Canning lived at No. 50. He was Foreign Secretary in 1809 when he fell out with Lord Castlereagh over sending troops to the continent. Canning plotted to have Castlereagh replaced as Secretary at War, but his opponent discovered what was going on and challenged him to a duel: ‘Under these circumstances, I must require that satisfaction from you to which I feel myself entitled to lay claim.’ Canning wounded Castlereagh in the thigh, sparking a political scandal.

Leave the square by Fitzmaurice Place to Curzon Street, which was highly fashionable and still retains some grand Georgian houses. No. 8 was the home of Mary and Agnes Berry, bluestocking sisters. Mary was an author and editor and together they held fashionable intellectual salons, which the Duke of Wellington often attended. As the evening drew on Mary would order their servant, ‘No more petticoats’, and he would extinguish the porch light, the signal for no more ladies to call.

Beau Brummell’s front door in Chesterfield Street.

Just after Half Moon Street there is an entrance to Shepherd Market, a characterful area for a detour. Now it is full of shops and places to eat but originally it was the location of the May Fair that gave this district its name.

A little further on the right hand side of Curzon Street is Crewe House, a rare example of a mid-eighteenth century London mansion that retains its original large site. If you linger to admire it you will get moved along by armed police – it is now the Saudi Arabian Embassy.

Getting dressed was a complex operation for a fashionable young man. This gentleman has received an unwelcome interruption as he pulls on his tight Hessian boots after breakfast. The parish beadle, accompanied by an aggrieved father, accuses the valet of seducing a serving maid.

The next right turn brings us into Chesterfield Street, an almost intact Georgian street. Beau Brummell lived at No. 4 from 1799 when he arrived in London until debt forced him to move to cheaper accommodation. Even his boot scraper is still in place, and it is easy to imagine him dressing in a leisurely manner whilst chatting to his admiring audience of friends, before leaving around noon for the shops or his club. When it rained, he would have taken a sedan chair – he considered Hackney carriages unfit for a gentleman.

A young lady listens attentively to the sermon from her high-sided private box pew. She is wearing Morning Dress in this plate of October 1810 in Ackermann’s Repository.

Turn right at the top of the street into Charles Street and then left into Chesterfield Hill. All through this area we are climbing up and down the banks of the Tyburn, which still runs beneath the streets.

Chesterfield Hill retains some of its 1750s houses, for example Nos. 12 and 15. Hay’s Mews crosses the street – its size gives a good indication of the number of horses and carriages kept in this prosperous area.

Turn left into Hill Street where Admiral Crawford lived. In Mansfield Park Henry Crawford tells Fanny Price that he travelled to London to introduce her brother to the admiral in the hope that he would exert his influence to help the young man’s career.

Beau Brummell knew this area well. This is a detail from Irena Sedlecka’s statue, erected in 2002 at the end of the Piccadilly Arcade, which we visit in Walk 4

Hill Street leads us to South Audley Street, always a mixed street of houses and high-class shops. Turn right to Grosvenor Chapel, one of the eighteenth-century ‘chapels of ease’ built to serve the upper-class inhabitants of the new developments. Private pews were charged for annually – pew rents – and this gave the speculative builders their profit.

Opposite is Aldford Street, originally Chapel Street. Beau Brummell lived at No. 13 in 1816 and Harriet Westbrooke was residing at No. 23 when Shelley eloped with her in 1811.

Purdey’s, the gunsmiths, dates from 1814. James Purdey had made gunstocks for Joseph Manton’s as chief stocker and any gentleman who could afford it would buy his guns from Purdey or from one of the Manton brothers.

The present premises of Purdey’s were built by James Purdey the Younger in 1880 and the damage to the marble pillars was caused by a bomb in 1941.

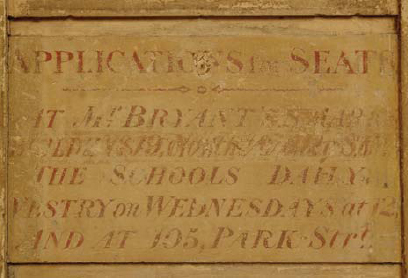

An antique painted sign on St Mark’s Church advertising pews to rent. Every respectable family would expect to occupy its own pew with the servants sitting separately at the back of the church or in a gallery.

South Audley Street ends at Grosvenor Square, the second largest square in London. It dates from 1725, although the houses around it have been extensively rebuilt, and it has always been highly fashionable and exclusive.

Turn right to reach Grosvenor Street. In Pride and Prejudice Mr and Mrs Hurst have a house here and Jane Bennett, hoping in vain for a visit from Mr Bingley, calls there on his sister Caroline, only to be fobbed off with the excuse that he was well, but much engaged with Mr Darcy and hardly ever at home.

Cross the square by cutting diagonally across the gardens in the centre to North Audley Street. Follow it to turn into Green Street, opposite St Mark’s Church.

Green Street crosses Park Street. On the corner was Park Street Chapel where Doctor James Stanier Clarke, Jane’s acquaintance from Carlton House, preached on Christmas Day 1815.

In Sense and Sensibility Lucy Steele spitefully tells Elinor that she is betrothed and Elinor protests that she cannot mean the Edward Ferrars that she knows. Lucy retorts, ‘Edward Ferrars, the eldest son of Mrs. Ferrars, of Park Street, and brother of your sister-in-law, Mrs. John Dashwood, is the person I mean; you must allow that I am not likely to be deceived as to the name of the man on who all my happiness depends.’

Turn right to reach Oxford Street and the end of this walk.