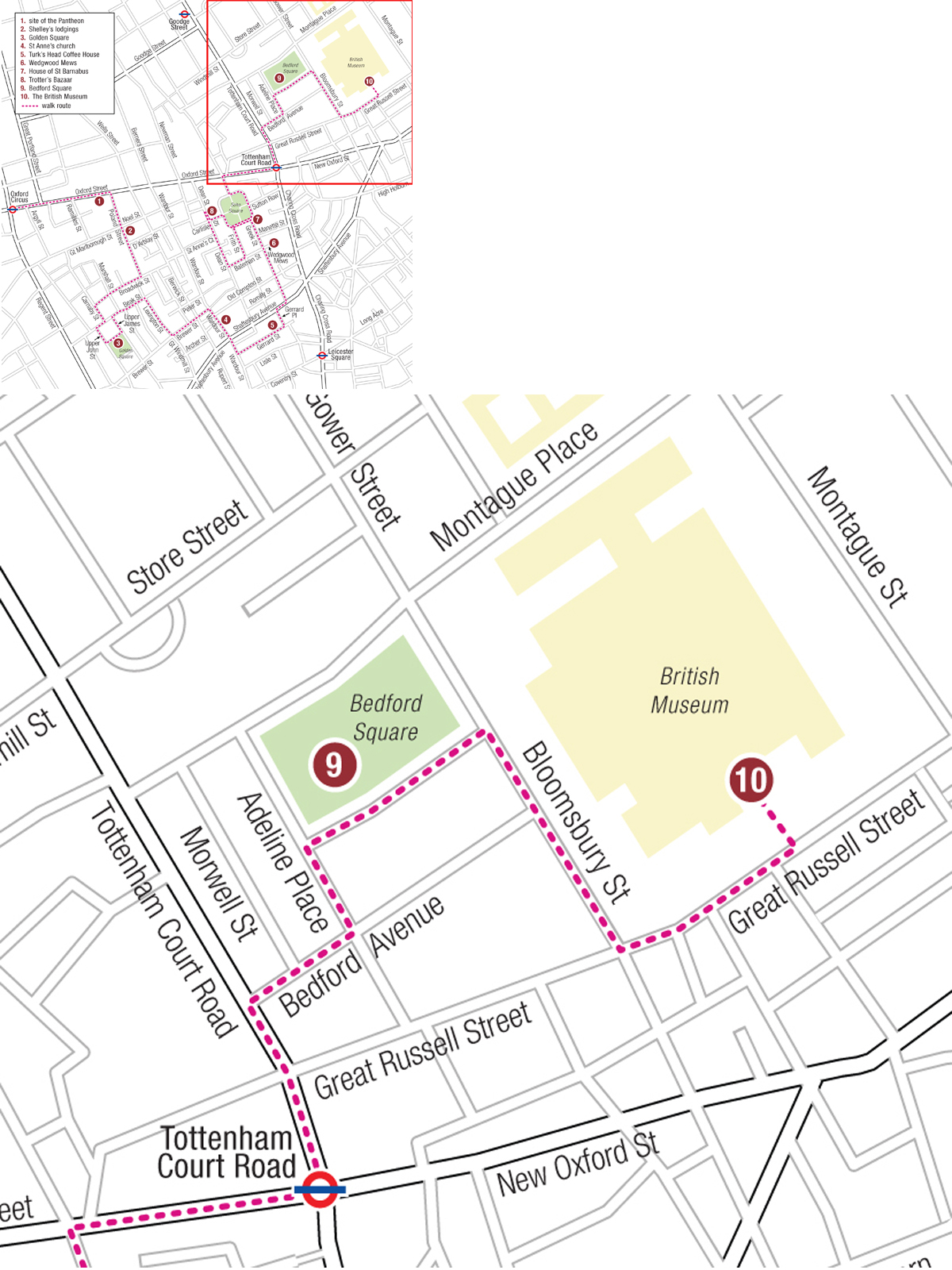

Starting location and nearest tube station: Oxford Circus.

Length: 2.5 miles.

Opening hours:

• ST ANNE’S CHURCHYARD: summer 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.; winter 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

• BRITISH MUSEUM: www.britishmuseum.org. Open daily from 10 a.m. to 5.30 p.m.; Fridays until 8.30 p.m.

A gingerbread seller. The text with this print of 1804 tells us: ‘Hot Spiced Gingerbread, sold in oblong flat cakes of one halfpenny each, very well made, well baked, and kept extremely hot, is a very pleasing regale to the pedestrians of London in cold and gloomy evenings.’

From Oxford Circus tube station walk east along Oxford Street to Marks and Spencer’s store. This is the site of the Pantheon, which was frequently rebuilt from 1772 and used for masquerades, assemblies and concerts, including the infamous Cyprians’ Balls, organised by the high-class courtesans. In 1833 it became the Pantheon Bazaar, finally demolished in 1937. Henry Austen rented a box here, although it is not mentioned in any of Jane’s letters.

Continue along Oxford Street, according to Ackermann’s Repository, ‘allowed to be one of the finest streets in Europe; the effect of which, when lighted in the evening, is very magnificent.’ Then turn right into Poland Street to enter the Soho district. The long streets of this area fossilise the pattern of fields from before its development in the seventeenth century.

The numerous pubs, shops and the small dwellings, many of them divided into lodging houses, presented a very different London from the smart ‘modern’ style of Sloane Street and Hans Place, or the elegance of Mayfair. This is a side of Jane Austen’s London that we do not visit often in her books or letters, but it was a real and vibrant part of it nonetheless.

When you reach the Coach and Horses pub, pause to look diagonally across to the corner of Noel Street and the house with a mural on the gable end. This is No. 15 where the poet Shelley stayed in 1811 when he was sent down from Oxford. Passionate about Polish freedom, he apparently chose his lodgings by the street name.

The Pantheon, Oxford Street, in 1814. All the premises beside it are shops: even at this date Oxford Street was predominantly retail and one of the major shopping destinations in London.

Singer Elizabeth Billington, known as the Poland Street Mantrap, mistress of both the Duke of Rutland and George, Prince of Wales, lived at No. 54 until 1792. Possibly she visited No. 56, the shop of J. Delcroix, to buy his ‘Cream de Sultanes’, advertised as ‘a preparation which, for embellishing the skin and heightening the charms of personal beauty, is unrivalled.’

Turn right into Broadwick Street and follow it to Carnaby Street, a busy general market until 1820. The area housed Huguenot refugees in the seventeenth century and remained very much a quarter of shopkeepers and tradesmen with a reputation for first-rate poulterers, porkmen and fishmongers.

Turn left into Carnaby Street, then right into Beak Street and take Upper John Street to Golden Square. The house of Doctor James Stanier Clarke, the Royal Librarian who showed Jane around Carlton House, was on the north side at No. 37. In December 1815 he wrote to her to offer the use of his personal library and to assure her that there was always a maid in attendance. There is no record of Jane’s response to the shocking invitation to visit an unmarried man’s home.

An 1818 bill from the Lion Brewhouse in Broad Street, now Broadwick Street. Beer was a much safer drink than water; in 1854 Doctor John Snow finally proved the connection between contaminated water supply and cholera with evidence gathered following the deaths of users of a pump on this site.

Return to Beak Street by Upper James Street, turn right and continue to No. 65, the start of a row of houses with early nineteenth-century shop fronts interrupted by an incongruous pub façade of 1847.

The battered statue of George II in the centre H5H of Golden Square.

Turning right down Lexington Street brings us to the junction with Brewer Street where Great Windmill Street’s curves preserve the line of an ancient track from what is now Piccadilly Circus to a windmill that stood in the fields close by.

If you turn left along Brewer Street then right into Wardour Street you will find the gardens and remains of St Anne’s Church behind a forbidding modern screen. From the 1630s to the mid-nineteenth century an estimated 100,000 people were buried in the ¾-acre churchyard: no wonder the ground is so raised. A memorial on the wall remembers the extraordinary ‘King of Corsica’, a German adventurer who ended his days in debtors’ prison, leaving his kingdom to his creditors.

Continue down Wardour Street, crossing Shaftesbury Avenue. In the Georgian period Wardour Street was known for its furniture and antiques shops. Thomas Sheraton, the designer, lived here until 1800.

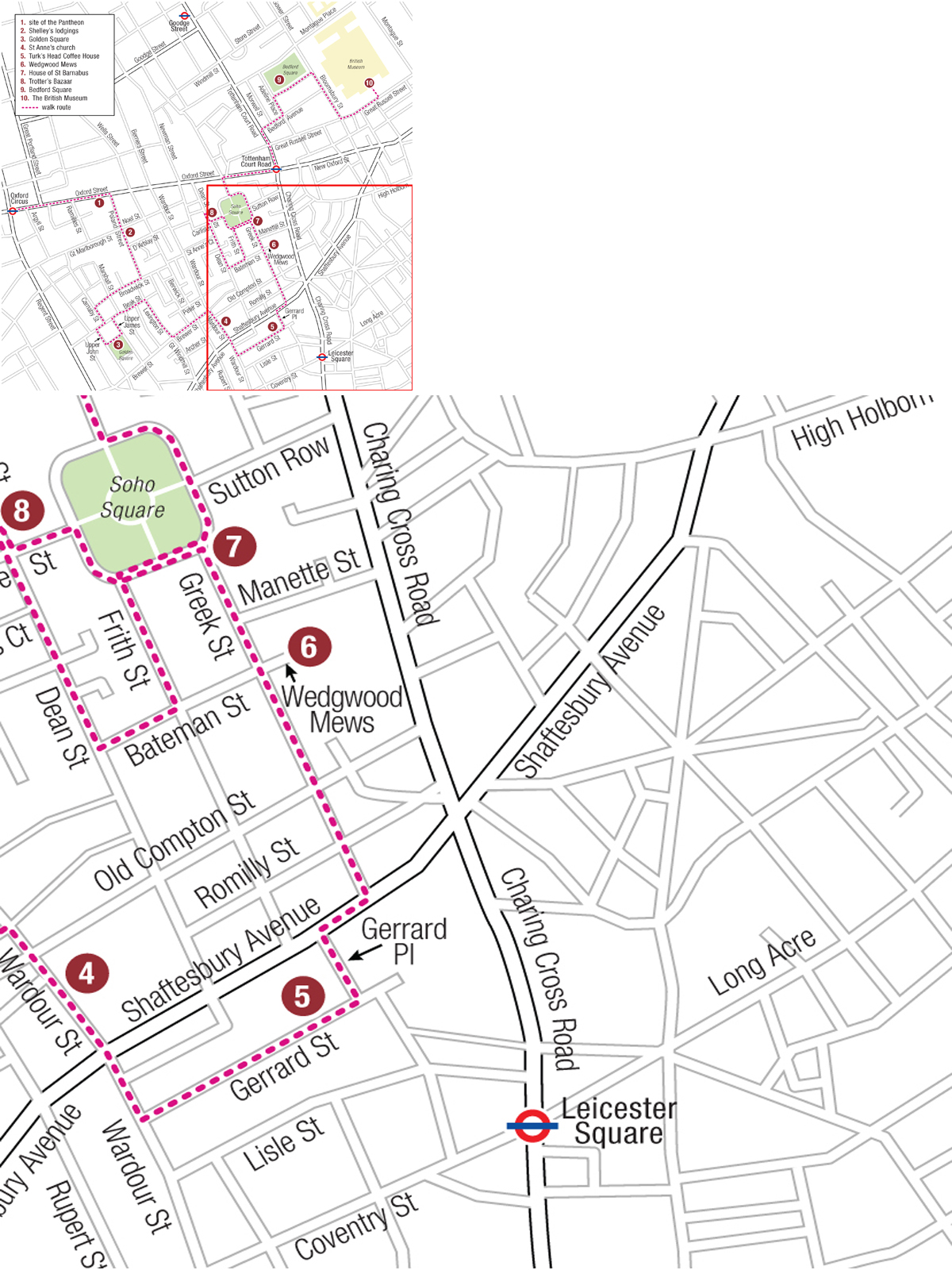

Turn left into Gerrard Street. Today it is the heart of Chinatown but during the eighteenth century and into the Regency it was full of coffee houses, taverns and lodgings: a focus for creative types. Artists such as John Sell Cotman lived here, as well as actors, including Charles Kemble.

On the left hand side is No. 9. Now a Chinese supermarket, this was originally the famous Turk’s Head coffee house, home from home to the likes of Doctor Johnson and Joshua Reynolds. You can climb the eighteenth-century staircase at the back of the shop, just as they did.

Turn left into Gerrard Place, right along Shaftesbury Avenue, then first left into Greek Street to Old Compton Street. This was a vibrant French community during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and has always been full of shops and restaurants rather than houses.

Beak Street: one of many early nineteenth-century shop fronts in Soho.

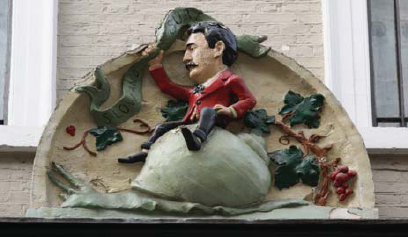

The sign of L’Escargot restaurant in Greek Street, one of the numerous French eating houses that have flourished in the area since the seventeenth century.

Continue along Greek Street, where Casanova lived at No. 47 in 1764. Thomas de Quincey, author of Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, ran away from school to seedy lodgings at No. 58 in 1802. No. 20 retains the iron hoist from the original colourman’s shop and, close by, Nos. 17 and 21 have early nineteenth-century shop fronts.

An original bell-pull in the form of a tasselled rope at the House of St Barnabas.

Opposite Bateman Street is Wedgwood Mews, originally a late seventeenth-century house. Josiah Wedgwood had his showrooms here between 1774 and 1795 when he moved to St James’s Square and opened the shop where the Austens bought their china.

On the corner with Soho Square is the House of St Barnabas, home to Richard Beckford, a vastly rich Jamaica sugar magnate, reminding us just how much wealth in the period was built on the slave trade. Sir Thomas Lawrence, the fashionable painter of spectacular Regency portraits, lived at No. 57 on the opposite corner between 1790 and 1794.

Turn left into Soho Square. The corner in front of you is the one shown in the Ackermann print, although finding cattle and sheep being herded through these days is unlikely! Nos. 33–5, now modern buildings, was the site of the house of the great naturalist Sir Joseph Banks.

Turn into Carlisle Street and right into Dean Street. No. 6 is the back of 4–6 Soho Square, which was Trotter’s or The Soho Bazaar and gives a rare glimpse into the warehouse area of a Regency business. This popular covered market with two floors of stalls for millinery and fancy goods was opened in 1816 to help people, especially women, thrown out of work during the post-war slump. Counters could be hired daily at a rate of 3d a foot. It was such a success that it continued until 1885.

Returning along Dean Street, No. 88 is a newsagent with a fine and rare Rococo front – unique in London. Once it must have been a very smart shop indeed, perhaps a music shop, if the instruments in the carving are significant. Further along Dean Street, at the corner with Bateman Street, look up to see the inn sign for the Crown andTwo Chairmen pub – a reminder of a popular mode of transport.

Turn left into Bateman Street to reach Frith Street where John Constable lived (1810–11). No. 15 has a fine Gothic shop front (1816).

Return to Soho Square and continue around it to Soho Street, leading to Oxford Street. Walk along to Tottenham Court Road, turn left, then right into Bedford Avenue. Adeline Place will lead you to Bedford Square.

The south-west corner of Soho Square in 1812 with Frith Street to the left. Two men with dogs are herding cows and a flock of sheep with the aid of dogs. Perhaps they are heading for one of the local butchers who served the numerous eating houses in the area.

No. 88 Dean Street retains an unusual eighteenth-century Rococo shop front; it may originally have been a music shop.

Bedford Square is full of very well preserved period features. It was built in 1775–80 and had many distinguished residents.

The Lord Chancellor, Lord Eldon, lived at No. 6 between 1802 and 1819 and seems to have had rather a miserable time. Once when he was unwell he was visited by the Prince Regent, who refused to leave until he had badgered Eldon into appointing one of his cronies to Chancery. Then in 1815 he was besieged in his home by Corn Law rioters for three weeks – they even tied a noose to a lamp-post outside the house. To get to Parliament one of the highest officials in the land was reduced to sneaking through the gardens of the British Museum, escorted by John Townsend, a Bow Street Runner. And finally his daughter eloped from the house with architect George S. Repton, giving the cartoonists a field day at the Lord Chancellor’s expense.

Beau Brummell considered that a sedan chair was the only acceptable vehicle for a gentleman to use in town.

Leave the square by Bloomsbury Street, then left into Great Russell Street to the British Museum. The collection was moved here in 1759 to be housed in Montague House.

The Picture of London instructs:

Persons who wish to see the British Museum should apply at the Assembling Room on any Monday, Wednesday, or Friday, between ten and two when they will be required to inscribe their names and places of abode, in a book kept for that purpose. Five companies, of not more than 15 persons each, may be admitted in the course of the day, at the hours of 10, 11, 12, 1 and 2, when the attendant, whose turn it is, will conduct the companies through the house.

The original British Museum, replaced in 1823 with the building we see today.

Treasures amassed in these early years included Sir William Hamilton’s collection of antique vases; the Egyptian antiquities, including the Rosetta Stone, captured from the French in 1801 after the battle of Alexandria (still, in 1807, housed in a large shed near the entrance); and, in 1816, the marbles from the Parthenon collected by Lord Elgin. By 1823 work had begun on the building that houses the museum today.

The Regency and Georgian exhibits are in rooms 46–7 and contain examples of the high style of the period, including jewellery, porcelain, glass and objets d’art.

The British Museum has a tearoom and plenty of opportunities to sit down and rest after your walk.