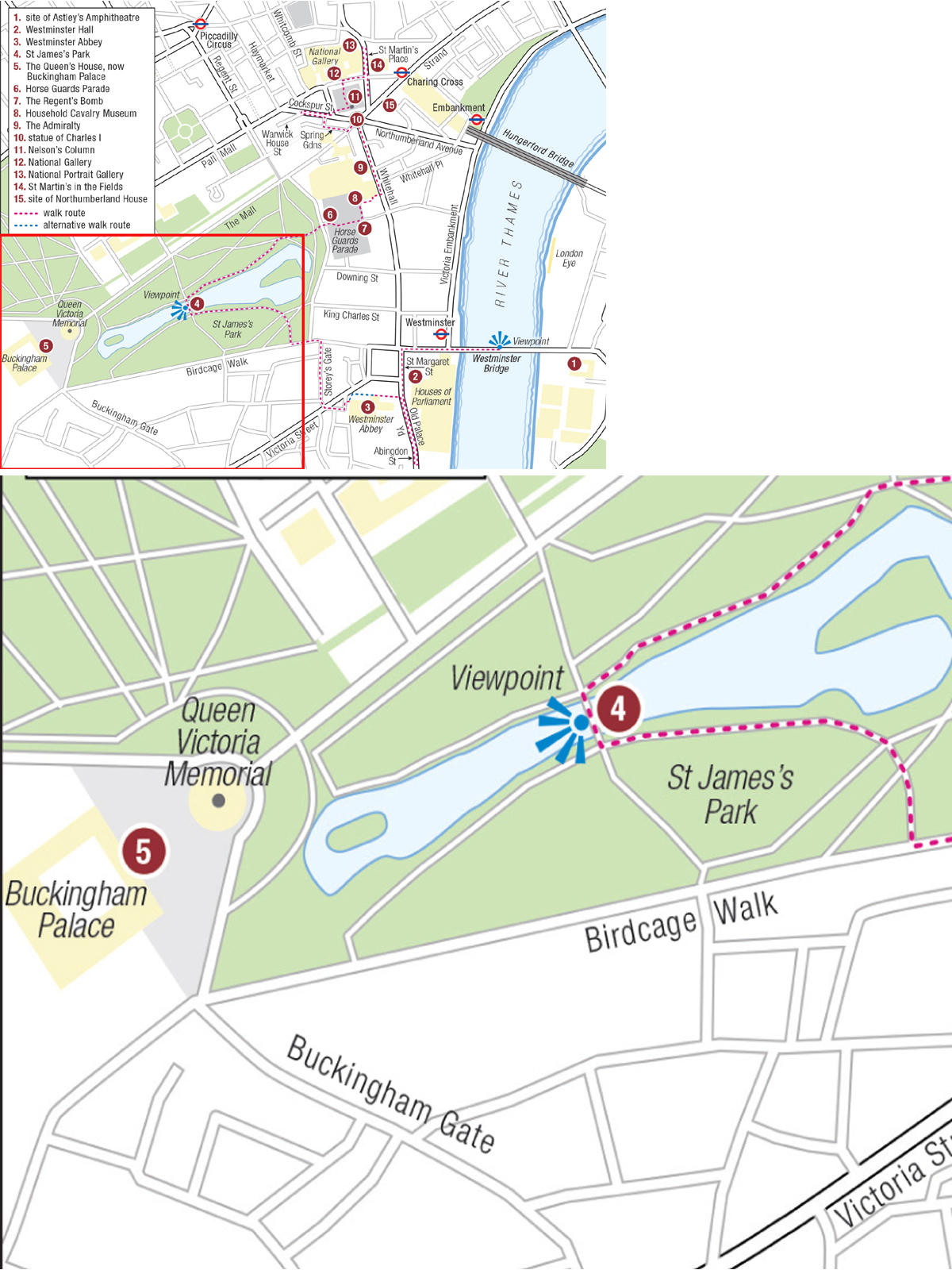

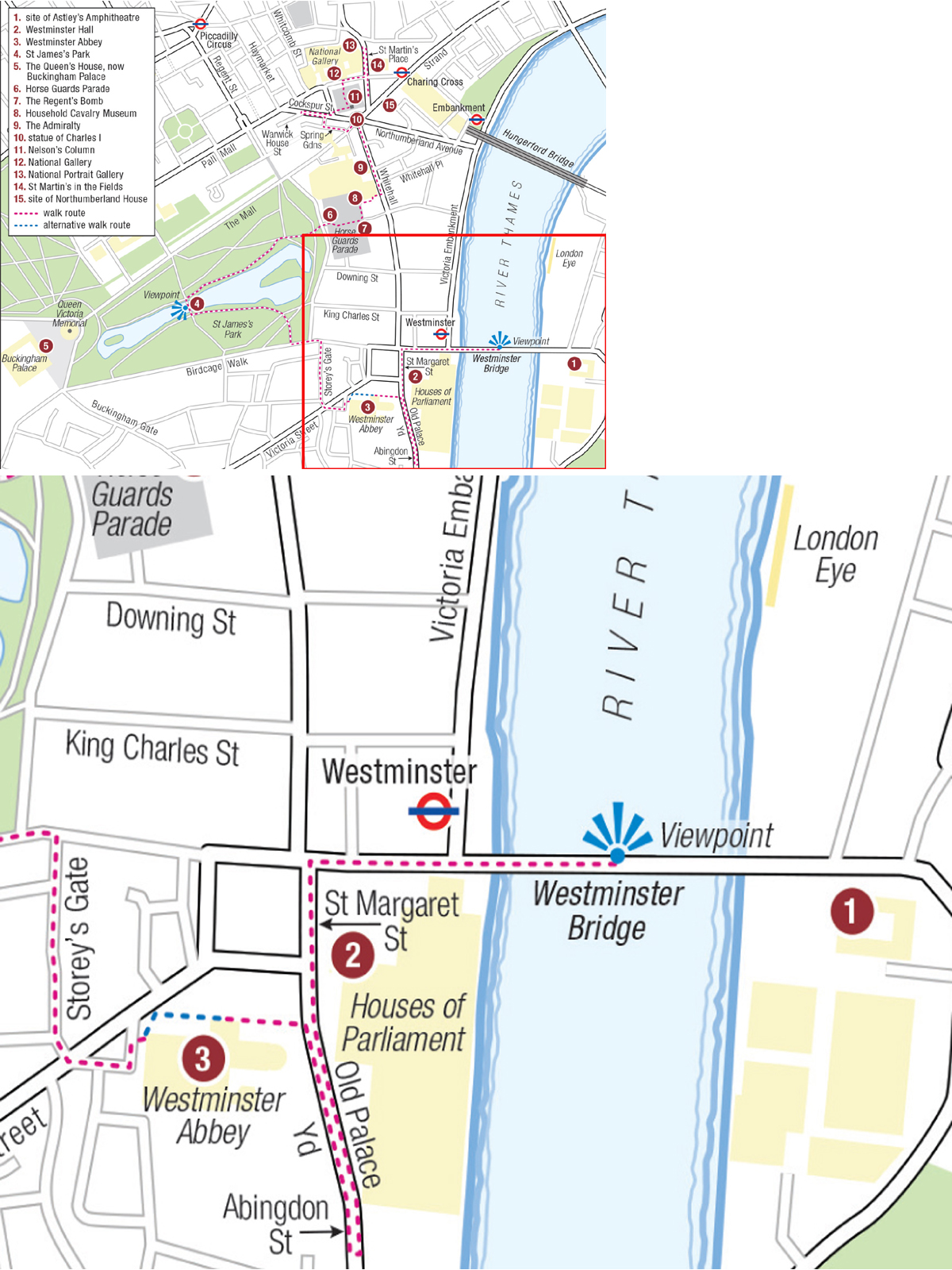

Starting location: the middle of Westminster Bridge.

Nearest tube station: Westminster.

Length: 2.5 miles.

Opening hours:

• WESTMINSTER ABBEY: www.westminster-abbey.org. The Abbey is generally open to tourists Monday to Friday and on Saturday mornings, but times vary considerably due to special services. It is always safest to check the website first.

• HOUSEHOLD CAVALRY MUSEUM: www.householdcavalrymuseum.co.uk. Open most days but hours vary seasonally.

• NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY: www.npg.org.uk. Open daily from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Thursday and Friday, open till 9 p.m.

• ST MARTIN IN THE FIELDS: www.smitf.org. The church is open for visitors during the day when services are not being held.

The first Westminster Bridge was completed in 1750 and was considered so handsome that it was painted by Canaletto. The arches gave a good echo and to try it out people would play musical instruments as they were rowed underneath.

One early morning in 1802 Wordsworth was inspired by the view to write the sonnet Upon Westminster Bridge – Earth has not anything to show so fair ... You can find the whole poem on a plaque at about the centre. The present bridge was built in 1862.

Astley’s Amphitheatre, where circus performances, equestrian exhibitions and popular extravaganzas were held, was located on the far bank. It was rebuilt frequently and finally demolished in 1893.

The view downstream from Westminster Bridge.

On 23 August 1796 Jane wrote to Cassandra that she had arrived safely in London and, ‘We are to be at Astley’s to night, which I am glad of.’ Unfortunately there is no record of what they saw or whether it lived up to expectations.

In Emma Harriet Smith and her admirer Robert Martin are reunited at Astley’s. Afterwards his heart was ‘very overflowing’ and ‘she could dwell on it all with the utmost delight.’

A playbill for Astley’s Amphitheatre for 10 November 1813. The programme gives a good indication of the melodramatic and exciting flavour of the typical Astley’s performance.

To add confusion for Austen scholars there was another Astley’s theatre, in the Strand, known by various names including Astley’s, Astley’s Pavilion and the Olympic Pavilion. So it is possible that Harriet and Robert’s tender moment happened there.

Walk back over the bridge and turn left into St Margaret Street. Ahead on your left is Westminster Hall and to the right is Westminster Abbey. Jane would recognise the Abbey but only the great medieval Westminster Hall survived the fire that destroyed the Palace of Westminster in 1834. In Persuasion Sir Walter twice met with William Elliot in the House of Commons lobby and Sir Thomas Bertram of Mansfield Park was a Member of Parliament.

Walk down past the front of the Houses of Parliament and when you reach the end, marked by the Victoria Tower, you are in Abingdon Street. This is where Charles Dundas, MP for Berkshire, lived when in London. Jane knew the Dundas family and it is this, and the proximity of Abingdon Street to Westminster Abbey, that has been put forward to support the identification of a portrait of a lady, with one of the Westminster Abbey towers in the background, as Jane Austen.

The old House of Commons seen from the Thames in 1830. As well as a working barge and a small passenger ferry, some pleasure boats with sightseers can be seen. Before flushing lavatories draining to the river became widespread in the 1820s, culminating in the Great Stink of 1858, a boat trip made a pleasant outing.

State and official horse-drawn carriages still arrive at the Palace of Westminster. Black Rod is the senior official responsible for security.

Cross the road and walk back towards the Abbey, round the corner to the Great North Door. (If the Abbey is closed, continue round to the Great West door).

One of the most dramatic incidents at Westminster Abbey was the extravagant coronation of George IV. It cost £240,000 and he barred his estranged queen, Caroline, from attending. She became desperate, running from door to door, crying to get in, but eventually she retired, defeated, to Hammersmith.

In Mansfield Park Dr Grant is appointed to an ecclesiastical position in the Abbey which – then as now – was packed with monuments and memorials. There are many of particular Georgian interest as we follow the fixed route around the Abbey.

In the North Aisle are George Canning (d. 1827) and Viscount Castlereagh (d. 1822) who duelled over government policy, Lord Palmerston (Secretary at War from 1809 to 1828), and Robert Peel (Home Secretary responsible for the Metropolitan Police force in 1829).

Westminster Abbey and St Margaret’s Church in 1810.

View of the Bridge & Pagoda St James’s Park Erected for the Grand Jubilee in Celebration of the Peace Under the Direction of Sir Wm. Congreave Bart.

On the left, Abbot Islip’s Chapel has memorials to Sir John Franklin (who fought at Trafalgar and led Arctic expeditions in 1819 and 1823); Thomas Telford the engineer; Humphrey Davy the chemist, and the actor John Philip Kemble.

In the South Transept is Poet’s Corner. Jane Austen is buried in Winchester Cathedral, but a plaque in her honour is here alongside Robert Southey, Robert Burns, Keats, Shelley, Coleridge, Byron and many other writers.

Buckingham Palace from the bridge in St James’s Park.

Following the route brings you into the Cloister and the Museum where there is a wax effigy of Nelson. It was made in 1806 and is dressed in his genuine clothes. Lady Nelson considered it most lifelike.

In the Nave there is a memorial to Pitt the Younger over the Great West Door. Nearby are monuments to Charles James Fox, with a slave at his feet to commemorate his efforts to abolish the trade; Spencer Perceval, the Prime Minister assassinated in 1812; William Wilberforce, another passionate campaigner against slavery; and Sir Stamford Raffles, founder of Singapore.

You leave the Abbey by the Great West Door. Crossing Broad Sanctuary to Storey’s Gate leads you to Birdcage Walk and the corner of St James’s Park. Enter and walk across to the bridge over the lake.

The park itself was a pleasant promenade by day but at night was a notorious haunt of prostitutes of both sexes. In 1814 it was the site of a series of extravagant celebrations: first for the centenary of Hanoverian rule; then the anniversary of the Battle of the Nile; and finally the peace celebrations following Napoleon’s exile to Elba. The architect Nash designed an exotic seven-storey pagoda, which unfortunately caught fire during a firework display, and a bridge, which lasted rather longer.

From the modern bridge there is an excellent view of Buckingham Palace. Jane knew it as the Queen’s House and it only took on its present appearance when George IV began its enlargement to fit his concept of a fitting palace. The façade facing down the Mall is twentieth century.

The Queen’s House before George IV’s remodelling to create Buckingham Palace. In this winter’s scene there are skaters on the lake in St James’s Park.

Cross the bridge and turn right to follow the lake shore back towards Whitehall, emerging onto Horse Guards Parade. In 1852 the funeral procession of the Duke of Wellington formed up here, the only location large enough to accommodate it.

To your right the southern boundary is formed by the garden wall of 10 Downing Street. Number 10 has been the official residence of the Prime Minister since 1732 and Beau Brummell was born here in 1778 when his father was private secretary to Lord North. Number 11 has been used by the Chancellor of the Exchequer since 1805.

In the early nineteenth century the Colonial Office was in Downing Street and it was there, in 1805, that Nelson and Wellington had their only encounter. Nelson’s thoughts were not recorded, but Wellington was unimpressed by the Admiral’s boastful manner.

Between the garden wall and the central archway you will find a squat black mortar captured during the battle of Salamanca in 1812. That battle resulted in the lifting of the siege of Cadiz and the mortar was presented to the Prince Regent, ‘as a token of respect and gratitude by the Spanish nation.’ The bizarre carriage in the shape of a Chinese dragon was made at Woolwich Arsenal. Regency guidebooks call the mortar ‘The Regent’s Bomb’. This proved irresistible to caricaturists who changed bomb to bum and produced numerous very cruel prints on the subject.

On the other side of the archway is a sixteenth-century cannon captured from the French at the Battle of Alexandria (1801). The gun carriage shows a rather strange crocodile and Britannia, who gestures towards the Pyramids.

There has been a collection of exotic waterfowl on the lake in St James’s Park ever since the Russian ambassador presented King Charles II with a pair of pelicans in 1664.

Next to the arch is the Household Cavalry Museum. In addition to the fascinating collection it is possible to see into the cavalry stables to watch the horses and their riders behind the scenes. Lydia Bennett would undoubtedly have approved of this.

Go through the central arch in the range, which was built between 1750 and 1759 to combine the barracks with offices for the Secretary at War. Turning left between the mounted guards onto Whitehall, you are almost immediately at the Admiralty, the buildings comprising the houses and offices of the Lords of the Admiralty.

Mounting Guard in 1809, drawn by Rowlandson, who was responsible for the figures, and Pugin, who drew the architecture surrounding Horse Guards Parade.

What you can see today would have been a familiar sight to Jane’s naval officer brothers, Charles and Frank. Their entire futures, their hopes of advancement, their very lives, were decided inside these buildings. Both entered the navy as boys and reached high rank – Frank as an admiral, Charles as a rear admiral – and both saw service across the globe.

If you look up you will see radio masts on the roof. In the early nineteenth century a telegraph in the same location sent messages down a relay of stations to the fleets at Portsmouth and Deal – a remarkable continuity of function, if not of technology. Regency visitors could see inside the rooftop telegraph huts if they tipped the porters – security seems to have been rather laxer in those days, or perhaps the authorities were confident that French spies could not read the codes.

It was to this building that Lieutenant Lapenotière, captain of HMS Pickle, brought the news of Trafalgar and the death of Nelson (21 October 1805). There are information plaques at the southern end of the Screen.

Frank Austen, to his lasting chagrin, was on escort duty to Malta and missed Trafalgar. He wrote, ‘To lose all share in the glory of a day which surpasses all which ever went before, is what I cannot think of with any degree of patience.’

A trooper on guard at the gates onto Whitehall patiently ignores the tourists.

In Mansfield Park Admiral Crawford uses his influence at the Admiralty to secure William Price a post as Second Lieutenant of H.M. Sloop Thrush.

Continue up Whitehall to the Charles I statue and turn sharp left into Pall Mall. Ahead is Admiralty Arch (1908–11). Turn into Spring Gardens, the remnant of a pleasure garden dating from Elizabethan days, which originally covered a considerable area at this end of St James’s Park.

The Picture of London (1807) recommends Wigley’s Royal Promenade rooms here. They were open from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m.; admission was one shilling. The visitor could ‘meet’ two invisible girls who spoke or sang on demand, or listen to a performance on the panharmonium, a mechanical orchestra.

Rather more intellectual were the exhibitions of The Society of Painters In Water Colours. On 24 May 1813 Jane wrote of a visit with her brother Henry and reported that she was well-pleased with what she saw, especially with:

… a small portrait of Mrs Bingley … exactly herself, size, shaped face, features & sweetness; there never was a greater likeness. She is dressed in a white gown, with green ornaments, which convinces me of what I had always supposed, that green was a favourite colour with her.

The Admiralty in 1830. The black masts above the roof in the centre are telegraph towers.

Jane enjoyed finding her characters in works of art and this, which Deirdre le Faye identifies as the charming Portrait of a Lady by J. F.-M. Huet-Villiers, made her think of Lizzie Bennett’s sister Jane in Pride and Prejudice.

Spring Gardens turns sharp right and then enters Cockspur Street. Farrance’s confectioner’s shop was situated on this corner. It served pastries and ices and was very popular with ladies.

Turn left into Cockspur Street. Priscilla Wakefield tells us that the shops here were, ‘of unparalleled elegance, particularly those of cut-glass and jewellery.’ A short distance along is Warwick House Street, the drab remains of Warwick Street, which once terminated at the gates of Warwick House.

Warwick House, ‘The residence of a princess to whose hand the sceptre of the British empire will in all probability be at some future period transmitted’, according to the text accompanying the print in Ackermann’s Repository in 1812. The unfortunate Princess Charlotte died in childbirth in 1817.

Part of the interior of the King’s Mews in 1808. It seems more of a palace for horses than a stables.

The Prince Regent insisted that Princess Charlotte lived here in order to separate her from the influence of his estranged wife Princess Caroline. On 16 July 1814 Charlotte, who was in disgrace with her father for flirting, left the house, scrambled into the first hackney carriage she saw in Cockspur Street and ran away to her mother who was living in Connaught Place.

Retrace your steps towards Trafalgar Square and cross to look at the bronze plaques around Nelson’s Column. They were cast from captured French cannon and show the battles of Cape St Vincent, Nile and Copenhagen and Nelson’s death at Trafalgar. With two brothers in the Navy, Jane and all the family would have had a keen interest in Nelson and the conduct of the war at sea.

From here you can walk across to the National Gallery, climb the steps and admire the view. The King’s Mews, designed by William Kent in 1732, stood on the site of the Gallery and the area in front of you was a mix of buildings grown up over the years like coral on a reef. They served at different times as virtually everything from a Civil Wa r barracks to a menagerie. In the centre of the area was the Golden Cross, a large coaching inn serving routes to the south of England. It was all swept away by John Nash’s Charing Cross improvement scheme andTrafalgar Square was paved, if not completed, by 1840.

The portico of the National Gallery with re-used pillars from Carlton House.

Charles I on his horse stares down Whitehall towards the site of his execution at the Banqueting House, while we look along the Strand with Northumberland House on the right (1811).

The National Gallery was begun in 1833. The bases and capitals of columns from the demolished Carlton House were used in the portico – virtually the only surviving physical trace of the building Jane visited in 1815 to discuss the dedication of Emma to the Prince Regent.

Turn towards the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields; go down the steps and around the corner into the National Portrait Gallery on the site of the vast St Martin’s Workhouse. The Gallery has a suite of rooms (second floor, 17–20) covering the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Here you come face to face with many of the leading lights of the period, including Nelson and Queen Caroline, both of whom we have met on this walk. There is also an interactive computer allowing you to search the collection so you can find your favourite Georgian character – including, of course, Jane Austen – and buy a print of their portrait.

Despite his best efforts, the Prince Regent was consistently depicted as a buffoon. Even the gulls and pigeons in Trafalgar Square today show scant regard for his dignity.

From the Gallery, cross over to St Martin-in-the-Fields, the only building in the area that Jane would recognise today.

Walk down with Trafalgar Square on your right until you reach the corner, where we end our walk. Jane was familiar with Charing Cross as the busy intersection of Whitehall, the Strand and Cockspur Street. She would have recognised the equestrian statue of Charles I in the middle of the traffic, but the rest of the scene would have baffled her. When Jane was here, perhaps to go shopping in the Strand, Trafalgar Square had not even been thought of. Standing beside her at the end of our walk, you would have been hemmed in by a chaotic jumble of buildings. St Martin’s Lane was a narrow street leading up to the church and to St Martin’s Workhouse and on the south side of the Strand was the vast Northumberland House.