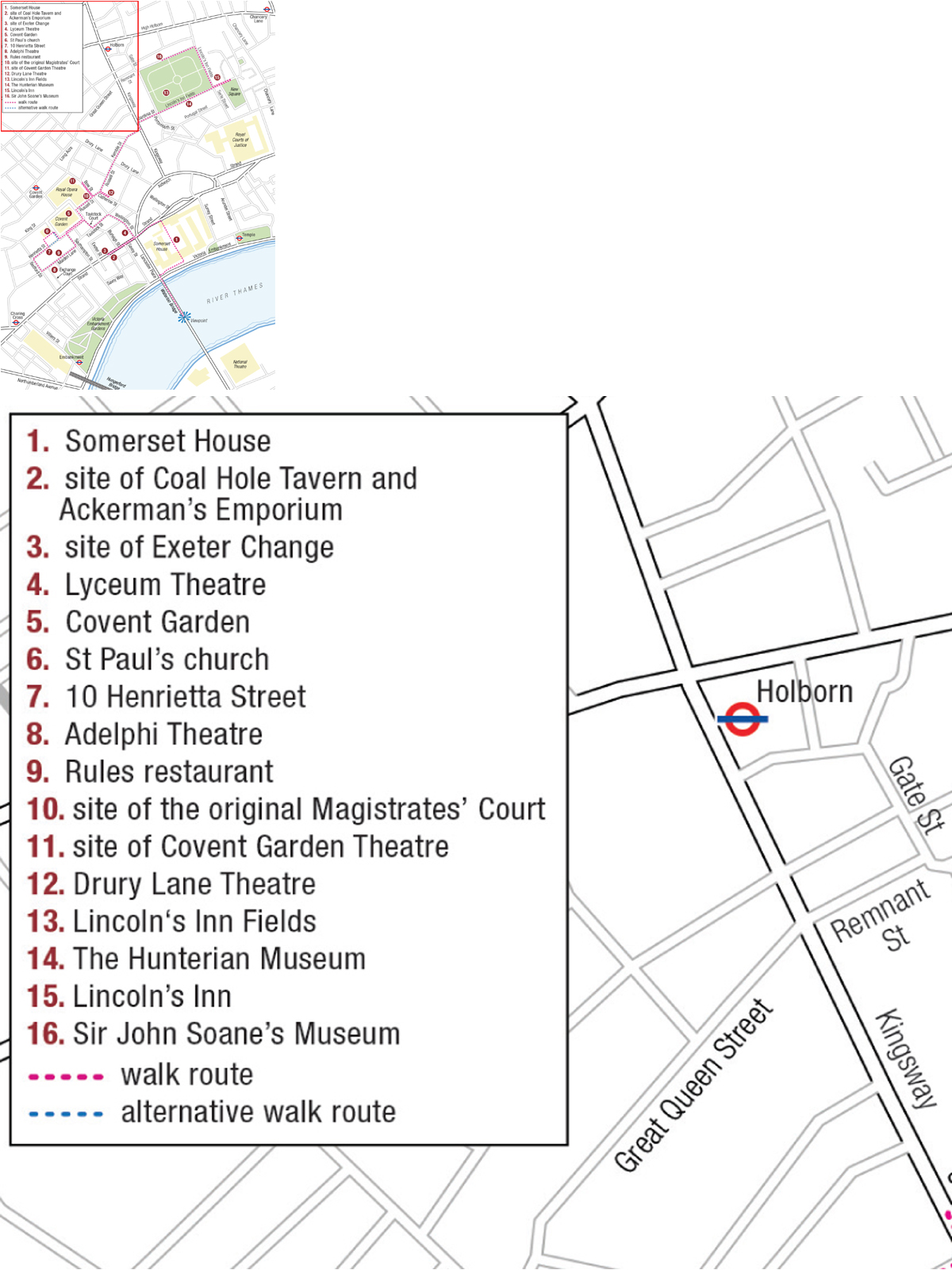

Starting location: Waterloo Bridge.

Nearest tube stations: Charing Cross, Embankment or Temple.

Length: 1.75 miles.

Opening hours:

• SOMERSET HOUSE: www.somersethouse.org.uk. Terrace and access through Seamen’s Hall to the central court open daily from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m.

• ST PAUL’S CHURCH, Covent Garden: www.actorschurch.org/church.html. Open Monday to Friday from 8.30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Saturday opening times vary. Open on Sunday from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. (5 p.m. when there is Evensong).

• THEATRE ROYAL Drury Lane: for theatre tours contact the box office.

• HUNTERIAN MUSEUM: www.rcseng.ac.uk/museums. Open Tuesday to Saturday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

• SIR JOHN SOANE’S MUSEUM: www.soane.org. Open Tuesday to Saturday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., last admission 4.30 p.m. Closed Bank Holidays. Numbers are often restricted, so it is best to check the website first.

• LINCOLN’S INN: www.lincolnsinn.org.uk. The grounds are open Monday to Friday, 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. Visit inside the buildings only with a guided tour (see website).

Tip: Plan your visit carefully with reference to the opening hours above. Covent Garden is very busy at the weekend.

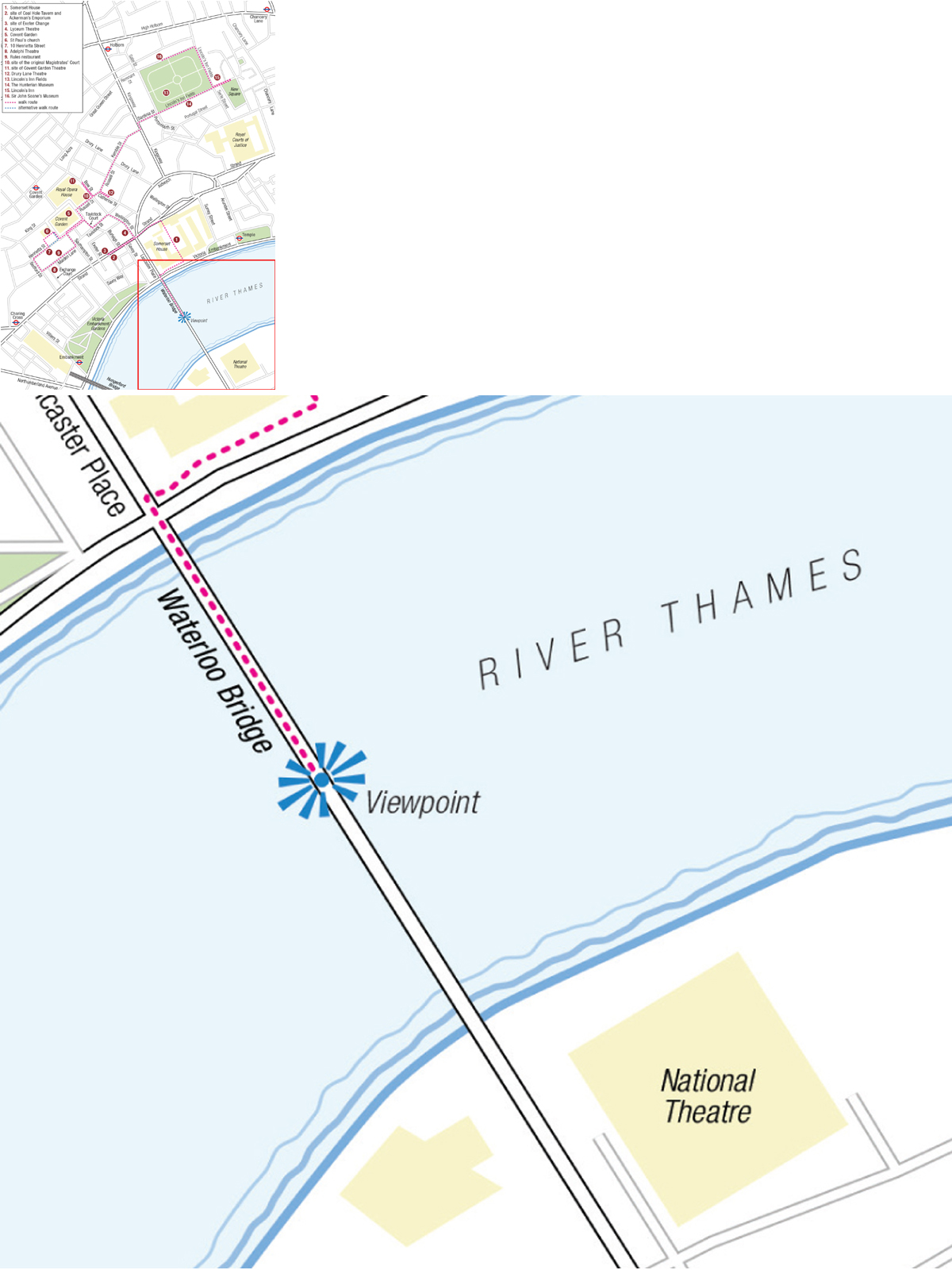

The view downstream from Waterloo Bridge. The ornate spire of St Bride’s Church (far left) and the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral (both Walk 8) contrast with the tower blocks of the City.

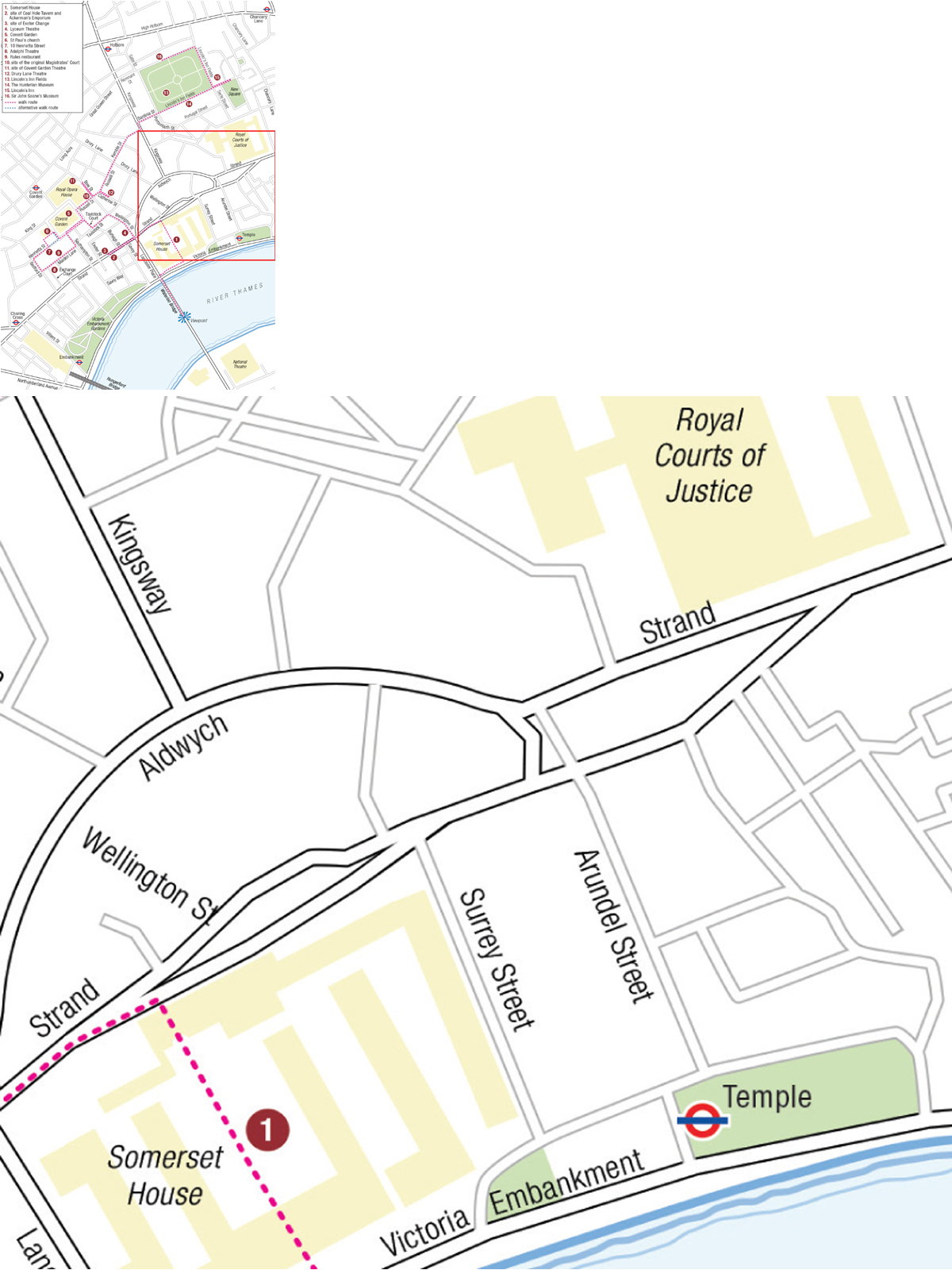

From the middle of Waterloo Bridge there are fine views upstream to Westminster and down to St Paul’s. The original bridge, designed by John Rennie, was opened by the Prince Regent a month before Jane Austen’s death on the second anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo (18 June 1817). It was replaced in 1937–42.

Walk back towards the Strand and, just as the bridge ends, turn right onto the River Terrace ramp to Somerset House. This terrace – the river frontage before the Embankment was constructed – was inaccessible to the public in Jane’s day, depriving them of ‘one of the noblest views in the world,’ according to The Picture of London.

A pair of mermen on the river frontage of Somerset House.

Enter Somerset House from the Terrace through the Seamen’s Hall and into the Fountain Court. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Somerset House housed the Royal Academy, the Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries and exhibitions and art shows here were a fashionable entertainment. Jane had planned to visit in May 1813, but an urgent errand intervened.

A crowded art exhibition in Somerset House with pictures crammed into every space and hung right up to the ceiling in the fashion of the time. This was a major social event during the Season, an excuse to see and be seen.

The Royal Navy occupied one wing throughout the Napoleonic wars, so Jane’s brothers Charles and Frank would have known Somerset House well. Cross the courtyard to leave by the Strand entrance.

The Strand is an ancient thoroughfare, dating back to the Normans, but constant redevelopment has left virtually nothing from before the mid-nineteenth century. It was a major shopping street during the late Georgian period, and one Jane would have been familiar with – in daylight, at least, because it had a very disreputable nightlife.

One of her letters records her intention to buy gloves from T. Remnant’s shop at No. 126 and she ordered tea from Twining’s, whose shop at the eastern end of the Strand we visit in Walk 8.

The view east along the Strand in 1809 to St Mary’s in the Strand, with the front of Somerset House on the right.

Turn left and walk along to the entrance to the Savoy. Just beyond, the Savoy Buildings cover the site of the Coal Hole tavern, a popular drinking house for actors and, at one time, a private theatre. Edmund Kean formed the Wolf Club drinking society, which met here. Reputedly it was for husbands whose wives did not permit them to sing in the bath!

Also under the Savoy Buildings is the site of Rudolph Ackermann’s Emporium at 101, Strand. Ackermann was a highly successful publisher, coach designer and enterprising retailer. He sold prints and artists’ materials and he published the iconic journal, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions etc (1809–29). It contains some of the most vivid images of Regency society, including many of the prints in this book. His was the first shop in London to be lit by gas in around 1807.

Cross to the north side of the Strand. Here, between Exeter Street and Burleigh Street, now the Strand Palace Hotel, was the Exeter Change, with small shops whose wares were, ‘principally of hardware, cutlery, and inferior jewellery’ (Priscilla Wakefield).

Pidcock’s (later Polito’s) Menagerie, a collection of exotic beasts and birds, was located on the floor above. As the exhibits were mostly live specimens and included a hippopotamus that Byron said resembled Lord Liverpool, as well as lions, tigers, an ostrich and a rhinoceros, the difficulty of keeping them must have been considerable.

In Sense and Sensibility one of John Dashwood’s feeble excuses for not calling promptly on his half-sisters was that he had to take his young son Harry to see the wild beasts here.

Polito’s Royal Menagerie, Exeter Change, in 1812.

The Lyceum Theatre in 1817. There is a demonstration of astrology in progress, typical of the sort of entertainments that the non-licensed theatres put on.

Continuing back along the Strand towards Somerset House brings us to Wellington Street. Turn left here to the Lyceum Theatre. The original theatre close to this site was built in 1771 and, after a spell as a circus, held varied entertainments, including displaying Madame Tussaud’s first waxworks exhibition in 1802.

Henry planned to take Jane there on 18 April 1811, but she had a cold and told Cassandra it would be postponed. However, two days later:

We did go to the play after all on Saturday, we went to the Lyceum, & saw the Hypocrite, an old play taken from Moliere’s Tartuffe, & were well entertained. Dowton & Matthews were the good actors. Mrs Edwin was the Heroine & her performance is just what it used to be. I have no chance of seeing Mrs Siddons. She did act on Monday, but as Henry was told by the Boxkeeper that he did not think she would, the places, & all thought of it, were given up. I should particularly have liked seeing her in Constance, & could swear at her with little effort for disappointing me.

A shop in this street that the Austens patronised by mail order was Penlington’s, a tallow chandlers at the sign of the Crown and Beehive, Charles Street (the name of the street at the time). It evidently produced superior candles, for on 1 November 1800 Jane tells Cassandra, who has just passed through London on her way to Kent, that their mother was ‘rather vexed’ because Cassandra did not call at Penlington’s but that she had sent a written order, ‘which does just as well.’

Continue up Wellington Street and turn left into Tavistock Street. This may be where the Austen family went to the dentist when in London. On 24 August 1814 Jane wrote, ‘My Brother & Edwd arrived last night … Their business is about Teeth & Wigs, & they are going after breakfast to Scarman’s & Tavistock St.’

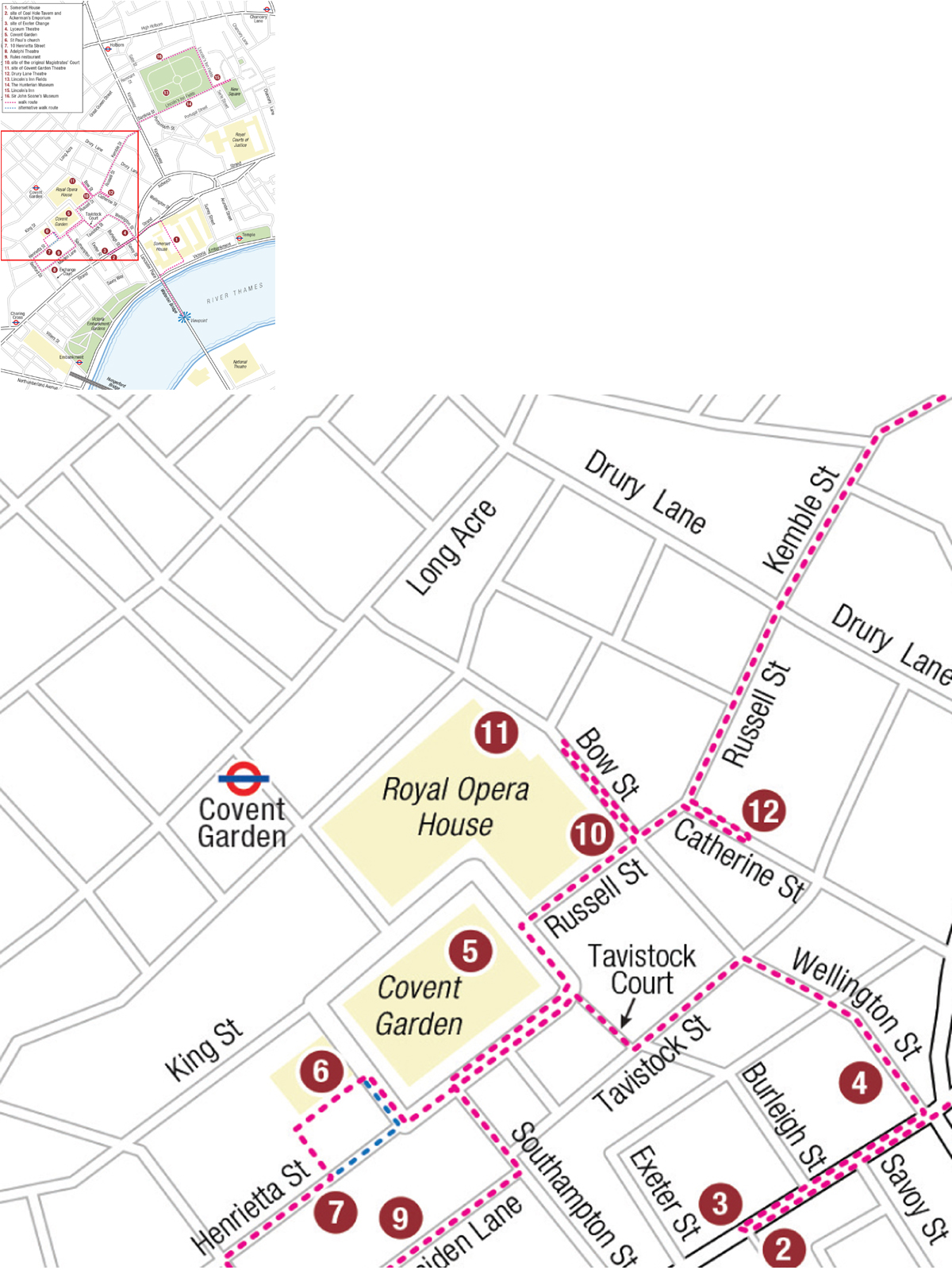

Tavistock Court leads to the Covent Garden piazza. The Covent Garden area was developed as a smart residential district in the early seventeenth century when the 4th Earl of Bedford commissioned Inigo Jones to create ‘houses fitt for the habitacions of Gentlemen and men of ability,’ around the first open public piazza in England.

After the Great Fire of London (1666), when many small markets were destroyed, it became a major fruit and flower market and the tone changed drastically. The homes of the wealthy were transformed into hotels, gaming houses, coffee houses and bath houses – hummums or bagnios – that were often nothing more than brothels. By the eighteenth century, Covent Garden was a major centre for entertainment and a by-word for vice at night, as well as being a market by day.

Turn left and walk along to the east portico of St Paul’s Church. If a member of the Austen family were to stand where you are now, the familiar scene before them would have been one of stalls and sheds – essentially a large-scale street market. The handsome neo-Classical buildings that fill the centre of the piazza were built between 1828 and 1830.

The essayist and poet Leigh Hunt wrote:

[Covent Garden market] has always been the most agreeable in the metropolis ... The country girls who bring the things to market at early dawn are a sight themselves worthy of the apples and roses ... And the Ladies who come to purchase, crown all. No walk in London on a fine summer’s day is more agreeable than the passage through the flowers here at noon when the roses and green leaves are newly watered...

The memorial to Charles Macklin in St Paul’s, the ‘Actors’ Church’. The comic actor died in 1797 aged 107.

But Ralph Rylance, author of The Epicure’s Almanac (1815) said that to walk home from the theatre involved ‘running the gauntlet thro’ streetwalkers and pickpockets.’

If the church is open, enter through the gate into the churchyard. (If the church is not open, turn right into Henrietta Street.)

St Paul’s, the nearest place of worship for a number of theatres, is known as the Actors’ Church. The Austens may have attended services here, for it is on Henry’s doorstep, but it is not mentioned in any of Jane’s letters.

The house in Henrietta Street where Henry Austen had his bank for several years and in which he lived between 1813 and 1814.

Turn left as you leave the church and the passage straight ahead will bring you out into Henrietta Street, immediately opposite No. 10 where Henry Austen had his bank offices. In 1813, following the death of his wife, he moved to the apartments above. After the respectable elegance of Sloane Street, living in Covent Garden would have been a startling contrast, although he must have known what to expect. Perhaps the colour and bustle were a welcome distraction from his bereavement. In May Jane described the apartments as being, ‘all dirt & confusion, but in a very promising way.’ The location does not seem to have given her any sisterly cause for concern.

When she arrived for a visit on 15 September 1813 with her brother Edward, his daughter Fanny and two of Fanny’s younger sisters, they had ‘a most comfortable dinner of Soup, Fish, Bouillee, Partridges & an apple Tart’ – probably in the dining room on the first floor at the front. Henry also had a sitting parlour and a small drawing room as well as the bedchambers. Jane and Fanny shared a bedroom with a little dressing room on the second floor and Edward stayed at a hotel in Maiden Lane.

Jane conjures up a charming family picture on 16 September: ‘We are now all four of us young Ladies sitting around the Circular Table in the inner room writing our Letters, while the two Brothers are having a comfortable coze in the room adjoining.’

In November she returned for a two-week stay while Henry negotiated the terms for Mansfield Park with Thomas Egerton’s publishing firm.

She was here again in March 1814, working on the proofs, and wrote on the 21st, ‘Perhaps before the end of April, Mansfield Park by the author of S. & S. – P. & P. may be in the World.’ It was actually published in May.

The royal coat of arms over the stage door of the Adelphi Theatre.

The ground floor is a shop now, although the upper part of the façade is more or less as Jane would have known it. The interior was virtually stripped out when it became a nurses’ home in the 1950s.

Henry moved back to Knightsbridge in mid-summer 1814. Perhaps, after all, he found Covent Garden noisy and disruptive and the apartment too small.

Next door, at No. 9, was Bedford House, the mercers’ shop of Layton and Shears. On 24 May 1813 Jane bought fabric there for her mother to have a gown made up – seven yards at six shillings and sixpence the yard. And in September she was shopping there again, looking at very pretty English and Irish poplins, a cloth made of silk and fine worsted.

At the end of Henrietta Street turn left and left again into Maiden Lane which retains a few eighteenth-century houses. On the right is Exchange Court, the site of the artist Turner’s birthplace. Further along on the same side is the Adelphi Theatre’s stage door. The present building is on the site of the Sans Pareil (1806), which became the Adelphi in 1819. It was popular for burlesques, melodramas, farces and pantomimes. Further along, Rules restaurant, which dates to 1798, still serves traditional English food, although in an atmosphere more redolent of the Edwardians than the Georgians.

Covent Garden is still full of stalls and crowded with shoppers, but these days they are buying gifts and crafts, not fruit and vegetables.

The view from the boxes to the stalls in the New Theatre (Theatre Royal), Covent Garden.

At the end of the road Southampton Street takes you back to the piazza. Covent Garden is full of shopping opportunities and places to eat and drink. When you are ready to move on, leave by Russell Street on the north-eastern edge. The building on the left-hand corner was the site of the Bedford Coffee House where the Beef-Steak Society moved in 1809. On the right-hand corner was Hummums Hotel, a bagnio with the brothel run by Mrs Gould, a notorious Madam, upstairs. Next to that were Lovejoy’s Bagnio and the Bedford Arms Tavern and bagnio.

Turn left into Bow Street, famous for its magistrates’ court and the Runners. No original buildings remain: the early magistrates’ court was on the western side of the street, where the goods entrance to the Opera House is now. In 1749 the second magistrate, Henry Fielding, founded the band of thief-takers who became known as Bow Street Runners. They remained an independent force even after the Metropolitan Police Act of 1829 and were finally disbanded in 1839.

The Royal Opera House is on the site of Covent Garden Theatre, which dated back to 1732. This burned down in 1808, dispossessing the Beef-Steak Society who would meet there to dine every Saturday evening between November and June. Members included the Prince Regent and his brothers the dukes of York and Sussex. Far more significantly, many of Handel’s manuscripts were lost in the fire.

The second theatre opened in 1809. It was so expensive to build that ticket prices were raised, sparking The Old Price Riots, which went on for sixty-one days until the prices were reduced. Mrs Siddons made her farewell performance here in 1812 and the theatre saw the first productions in English of Don Giovanni, The Barber of Seville and The Marriage of Figaro. The present building replaces the one that Jane knew, which burned down in 1855.

The Austen family were enthusiastic about drama; they wrote and performed their own plays and attended the theatre whenever possible. Jane had definite opinions on the productions, and the actors, that she saw.

On 16 September 1813 she told Cassandra:

Fanny & the two little girls are gone to take Places for tonight at Covent Garden; Clandestine Marriage & Midas. The latter will be a fine show for L. & M. They revelled last night in Don Juan, whom we left in Hell at ½ past 11. We had Scaramouch & a Ghost – and were delighted; I speak of them; my delight was very tranquil, & the rest of us were sober-minded.

One week that month she went to the theatre on two out of three evenings – to The Lyceum and Covent Garden. ‘There was no Actor worthy naming. I believe the Theatres are thought at a low ebb at present.’

The Drury Lane Theatre in 1812 with a small group of sightseers on the left admiring the new building.

Retrace your steps to Russell Street, and turn left to see the Theatre Royal Drury Lane ahead. Confusingly, it faces Catherine Street, not Drury Lane.

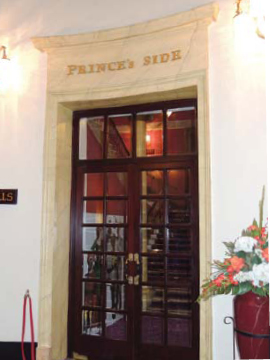

The door to the Prince’s Side in the lobby of Drury Lane Theatre.

Theatres on this site date back to 1663 and Nell Gwynne made her debut here. The original cellars, with charred remains of the stage floorboards on which she trod, are still intact and may be open if you take a tour.

From 1737 theatres had to be licensed to perform plays and the only two licences granted were for Drury Lane and Covent Garden. All the others had to skirt the law by putting on puppet shows, pantomimes, sketches, burlettas and musical versions of plays. As a result, the pressure on the two licensed theatres meant they became vast, with over three thousand seats each.

A new Drury Lane theatre was opened in 1794 and it was here that in 1800 an attempt was made on the life of George III. It burned down in 1809, the fire watched calmly by the manager Richard Brinsley Sheridan as he sipped a glass of wine by his ‘own fireside,’ as he wryly put it.

Rebuilt in 1811 –12, it is the oldest working theatre in London. Shortly after it was reopened, George III had a furious row with his son, the Prince Regent, in the circular lobby. As a result the management created a separate Prince’s Box facing the Royal Box so that each had his own entrance and retiring room. In Sense and Sensibility it is in the lobby that Willoughby learns of Marianne’s illness from Sir John Middleton.

Edmund Kean’s first appearance here was in 1814. On 3 March that year Jane wrote to Cassandra:

Places are secured at Drury Lane for Saturday, but so great is the rage for seeing Keen [sic] that only a 3d & 4th row could be got. As it is in a front box however, I hope we shall do pretty well ... There are no good Places to be got in Drury Lane for the next fortnight, but Henry means to secure some for Saturday fortnight when You are reckoned upon.

Statue of Edmund Kean in the lobby of Drury Lane Theatre.

In her next letter she reports:

We were quite satisfied with Kean. I cannot imagine better acting, but the part was too short, & excepting him & Miss Smith, & she did not quite answer my expectation, the parts were ill filled & the Play heavy. We were too much tired to stay for the whole of Illusion (Nourjahad) which has 3 acts; there is a great deal of finery & dancing in it, but I think little merit ... I shall like to see Kean again excessively, & to see him with You too; it appeared to me as if there were no fault in him anywhere; & in his scene with Tubal there was exquisite acting.

The view of Lincoln’s Inn Fields from the north-west in 1810.

The next day they returned and an acquaintance was urging them to go again the day after that. But Jane was coming down with a cold and the performance of Miss Stephens gave her, ‘little pleasure either in acting or singing.’

According to The Picture of London, boxes cost six shillings; seats in the pit were three shillings and sixpence; the gallery, two shillings; and the upper gallery, one shilling.

Continue along Russell Street into Kemble Street, a nineteenth-century road driven through a tangle of older thoroughfares, to reach Kingsway, which, with Aldwych to the south, was opened in 1905 to reduce the traffic congestion in the area. In the process a maze of ancient streets was swept away.

Cross to Sardinia Street, which leads to Lincoln’s Inn Fields, the largest square in London. Halfway along the southern edge you come to the Royal College of Surgeons and the Hunterian Museum. This is fascinating for anyone interested in Georgian surgery and medicine, but, with its dissections and human remains, definitely not if you are the slightest bit squeamish.

Continue to the main entrance of Lincoln’s Inn. This 11-acre enclave has been home to The Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn, one of the four ancient Inns of Court, or associations of barristers, since at least the fifteenth century.

Sir John Soane’s Museum.

It was to Lincoln’s Inn that Tom Lefroy, the young man with whom Jane enjoyed a flirtation – or perhaps something deeper – returned to his legal studies in 1796.

On 10 January that year Jane wrote to Cassandra to tell her about a ball she had attended at Manydown:

… I am almost afraid to tell you how my Irish friend [Tom Lefroy] and I behaved. Imagine to yourself everything most profligate and shocking in the way of dancing and sitting down together... He is a very gentlemanlike, good-looking, pleasant young man, I assure you.

However, Tom’s ambitious family opposed an alliance with the dowerless Miss Austen and Tom was packed off back to London and his studies before things could become too serious. Eventually he became Lord Chief Justice of Ireland.

Return to Lincoln’s Inn Fields and walk round to the northern edge and Sir John Soane’s Museum. The architect developed these houses as his own home between 1792 and 1824 and they have undergone extensive restoration and renovation. As well as being a busy and fashionable architect – he designed the Bank of England – Soane was an avid collector of paintings, casts, curiosities and antiquities, which remain in the elegant, and idiosyncratic, rooms he designed for them. The result is a highly atmospheric and evocative Regency experience with which to end your walk.