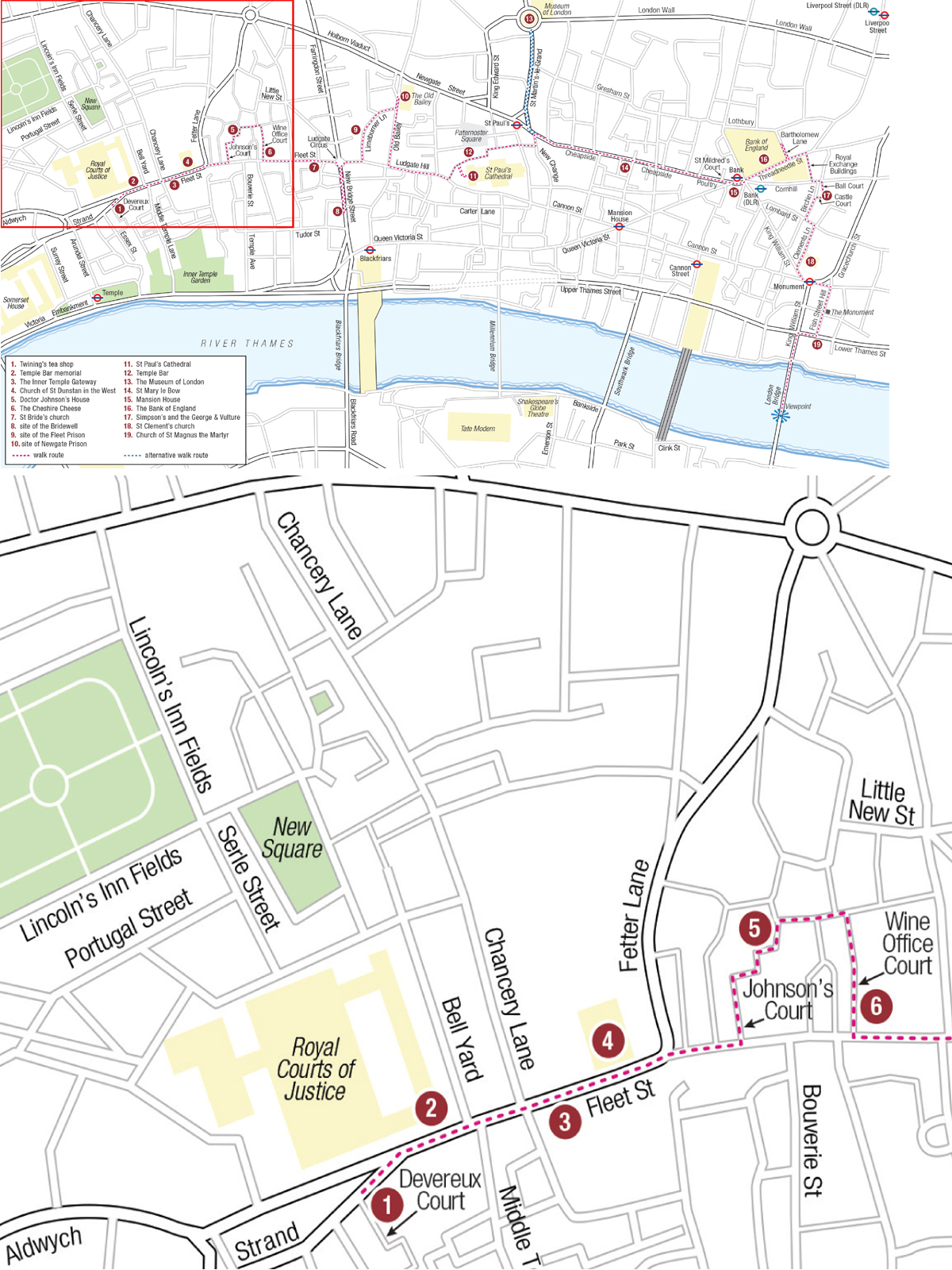

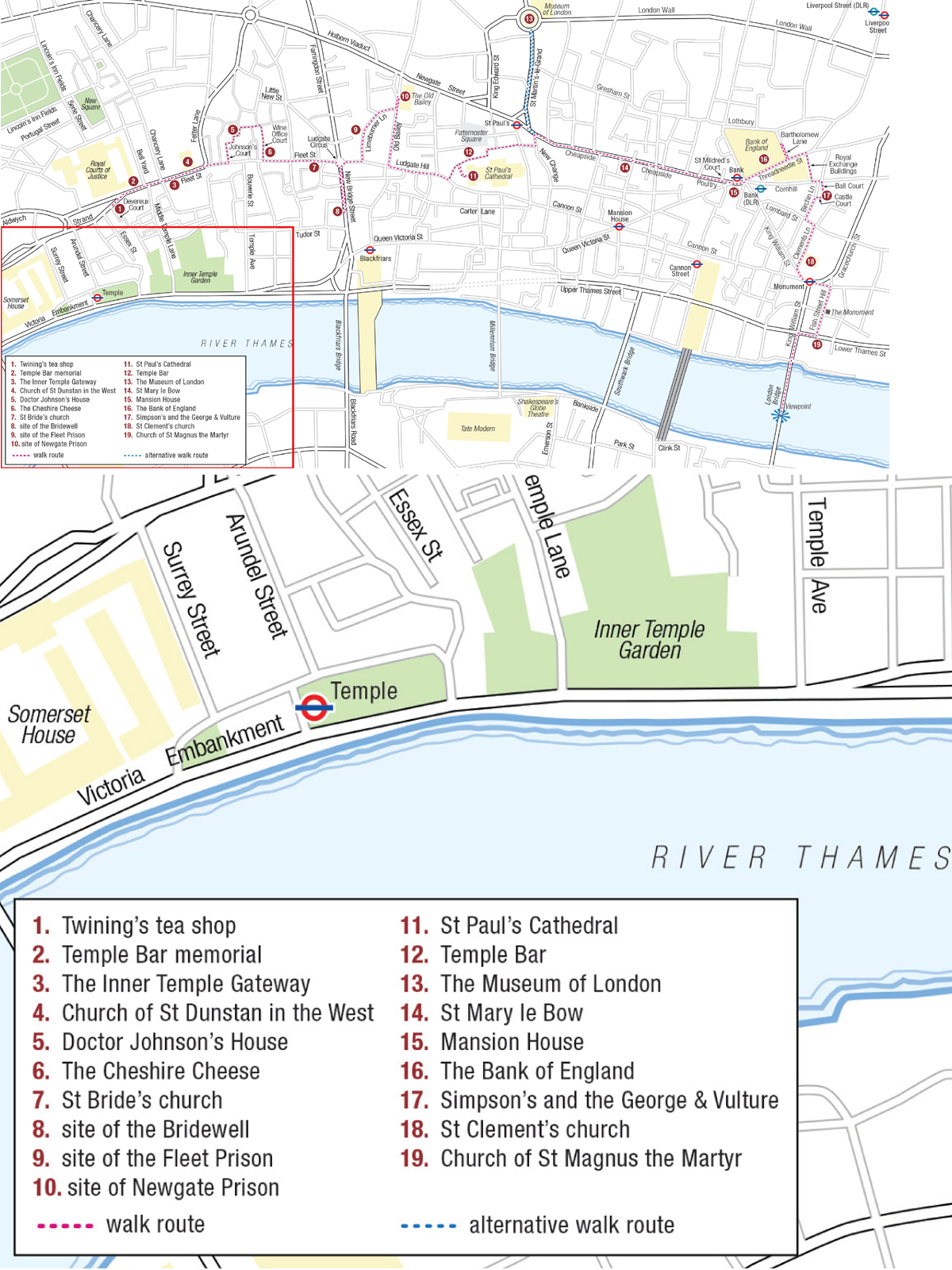

Starting location: Twining’s, 216 Strand.

Nearest tube station: Temple.

Length: 2.25 miles.

Opening hours:

• TWINING’S: Open every day except public holidays.

• DOCTOR JOHNSON’S HOUSE: www.drjohnsonshouse.org. Open Monday to Saturday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. (5.30 p.m. May to September).

• ST PAUL’S CATHEDRAL: www.stpauls.co.uk. Open for sightseeing, Monday to Saturday from 8.30 a.m. to 4.30 p.m. Last admission 4 p.m. See website for events and services.

• MUSEUM OF LONDON: www.museumoflondon.org.uk. Open daily from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Closed 24th to 26th December.

• BANK OF ENGLAND MUSEUM: www.bankofengland.co.uk/education/Pages/museum. Open Monday to Friday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Last admission 4.45 p.m. Closed on public holidays.

• THE MONUMENT: www.themonument.info. Open daily except some public holidays. Check website for details.

Tip: Most City pubs, restaurants and shops are closed on Saturday and Sunday. Generally the area is livelier Monday to Friday.

Historic London is actually two cities – Westminster, the seat of royalty and the abode of the fashionable to the west, and the City, the centre of commerce and finance, to the east. We begin this walk outside Twining’s the tea merchant, just before the point where the two meet at Temple Bar.

The entrance to Twining’s tea shop in the Strand.

In 1706 Thomas Twining bought Tom’s Coffee Shop in Devereux Court, the narrow opening just to the west before the half-timbered pub. Coffee drinking was very popular and Tom’s was well placed to attract City merchants and lawyers from the nearby Middle and Inner Temples. Tea was less popular because of high taxes, but Twining persisted in offering it and began selling dry tea as well as brewing it on the premises – this may be the world’s first dry tea and coffee shop.

The griffon from the City of London’s coat of arms rears up on the Temple Bar memorial, silhoue_ed against the Law Courts.

The original doorway (1787) with its pair of Chinese gentlemen is a reminder that all imported tea came from China until the East India Company introduced large commercial plantations into India in the 1820s. There is a fascinating collection of paintings, prints and antique tea caddies on display and a huge array of teas to try and to buy.

The Austen family bought their tea from Twining’s. In March 1814 Jane wrote to Cassandra from Henrietta Street, ‘I am sorry to hear there has been a rise in tea. I do not mean to pay Twining till later in the day, when we may order a fresh supply.’ A few days later she adds plaintively, ‘I suppose my Mother recollects that she gave me no Money for paying Brecknell & Twining; & my funds will not supply enough.’

Opposite are the Royal Courts of Justice, completed in 1882. A few steps east brings us to the Temple Bar memorial in the middle of the road, marking the spot where the Temple Bar gate stood from 1351 until 1878. This is the beginning of the City of London and even today, on ceremonial occasions, the monarch stops here to ask permission to enter the City. In return the Lord Mayor offers his Sword of State as a token of his allegiance. Ornate rests for these swords can be found in most City churches, for example in St Clement’s, which we visit later on this walk.

The Bar, which was draped in black velvet for Nelson’s funeral, was moved because it had become an obstruction to traffic – we will find it during this walk by St Paul’s. In Persuasion young Mr Elliot had chambers close by and, just past the Bar on the right hand side, there is the pedestrian entrance to Middle Temple Lane leading down to two of the Inns of Court, self-regulating societies of barristers.

Prince Henry’s Room above Inner Temple Gateway in 1807 with the advertisement for Mrs Salmon’s Waxworks.

The gatehouse should be open Monday to Friday and a diversion into Middle and Inner Temple reveals ancient buildings and some lovely gardens.

Staying on Fleet Street we come to the Inner Temple Gateway. This is a genuine survivor of the Great Fire and was built in 1610 (restored 1900). It contains Prince Henry’s Room, a panelled chamber with the Prince of Wales feathers in the plasterwork ceiling. In Jane Austen’s day it was the home of Mrs Salmon’s Waxworks.

Looking west along Fleet Street in 1812. Temple Bar is still in position and the old St Dunstan’s Church is squashed in behind shops on the right.

This collection, created in 1711, moved here in 1795. The displays included the execution of Charles I and a weird assortment of grotesque tableaux, some models even animated by clockwork. They included, ‘Margaret Countess of Heningbergh, Lying on a Bed of State, with her three hundred and Sixty-Five Children, all born at one Birth.’

A little further along, John Murray had his office at No. 32 on the corner of Falcon Court from 1762 until the move to Albemarle Street in 1812, a few years before he became Jane’s publisher.

When you reach St Dunstan’s Church, cross the road to look back the way you have come and compare the view with the print showing Temple Bar as it was in 1812. The old church was rebuilt in 1834 but the 1671 clock remains.

Continuing on the same side of the road we pass small courts and alleys, many of them named after long-vanished inns. Turn into Johnson’s Court and continue up to Gough Square and Doctor Johnson’s House.

From here you can make your way to Wine Office Court and Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, a favourite haunt of his. It began life as houses, built just after the Great Fire, but the façade onto the Court is eighteenth century. The interior is highly atmospheric, although the fittings are mostly early to mid-nineteenth century, rather than dating from Johnson’s day. It certainly gives an excellent idea of what a tavern interior must have been like in Jane’s time.

The elaborate ‘wedding cake’ tiers of St Bride’s spire seen from Ludgate Circus.

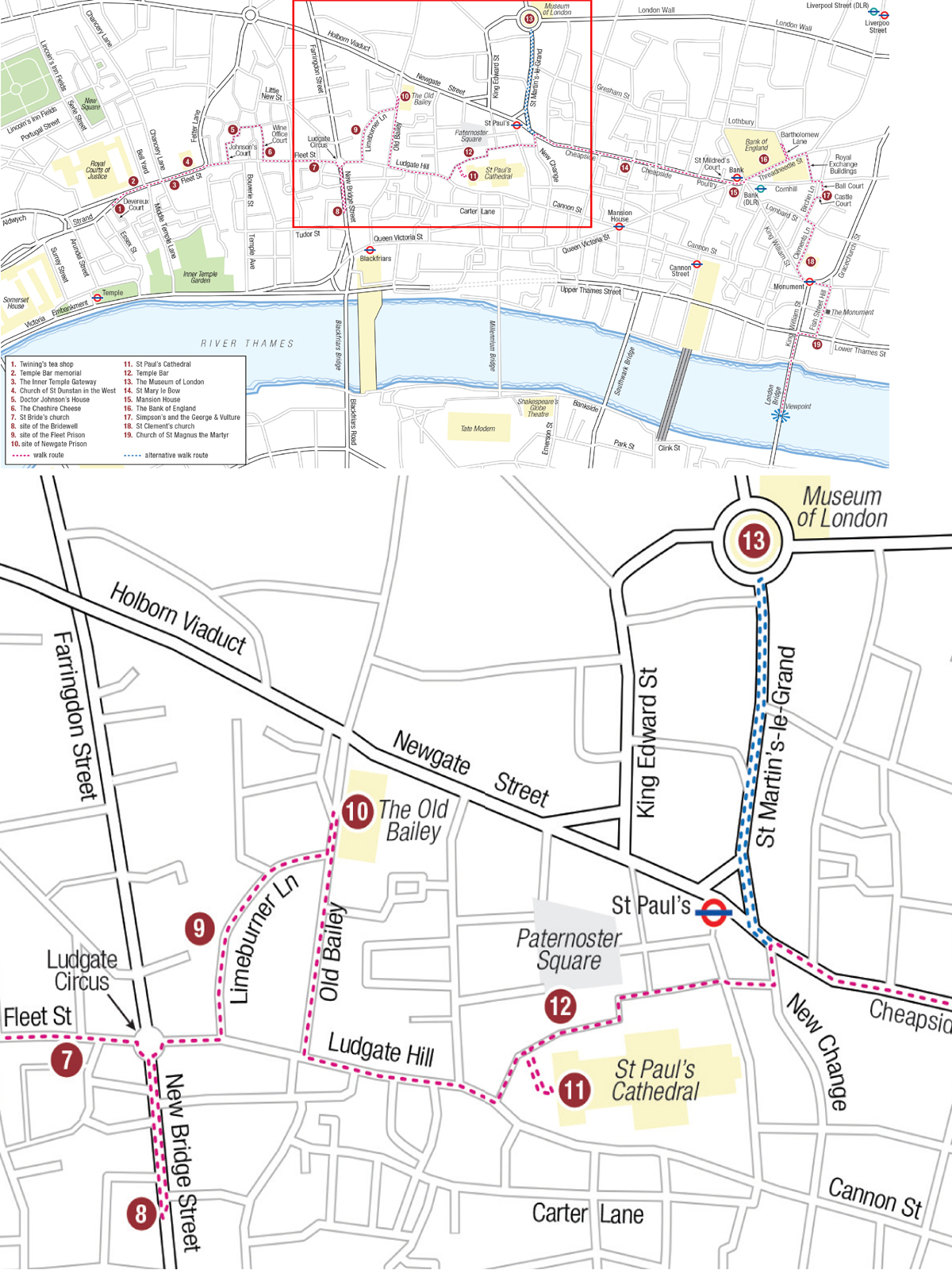

Rejoin Fleet Street, which leads us downhill into the valley of the River Fleet at Ludgate Circus. If you look up to the right as you descend you will see the Wren spire of St Bride’s Church. The legend is that it inspired Mr Rich, a Georgian pastry cook, to create the tiered wedding cakes that are now traditional.

Pause when you reach Ludgate Circus, built in 1864–75 on the site of the Fleet Bridge. To your left is Farringdon Street, formerly Fleet Market. The river was gradually covered over to give space for stalls until, by 1829, it was reduced to the mere drain that still runs down to the Thames beneath your feet.

The Pass-Room at the Bridewell in 1808. Single women with their babies are locked up for their ‘loose behaviour’. At least they had their own beds, even if the mattresses were simply a pile of straw.

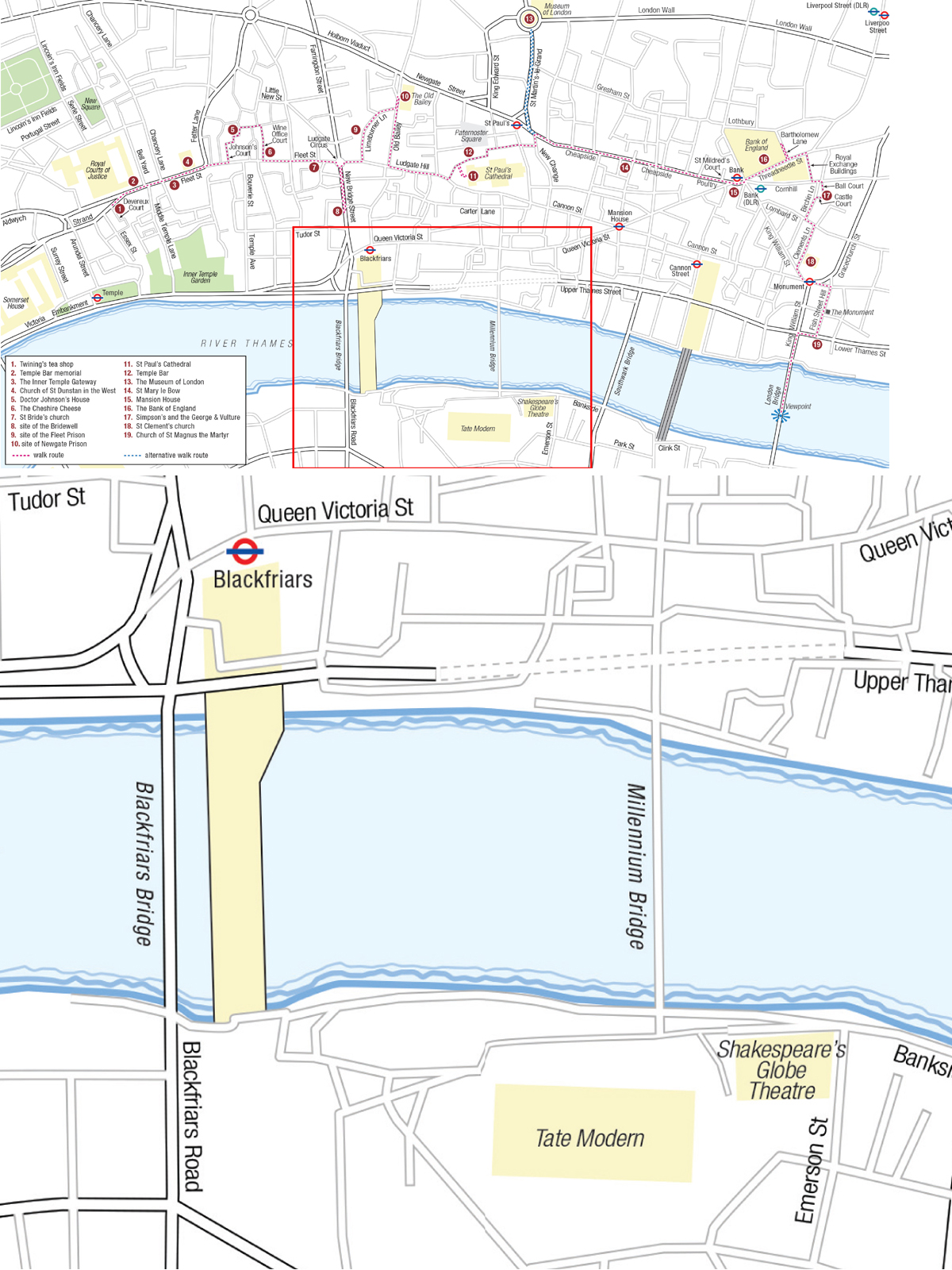

To the right is New Bridge Street, constructed in 1764 over the lower part of the river, which by then had become a foetid sewer. The new street provided access to the first Blackfriars Bridge, opened in 1769. It was replaced with the present bridge in 1869.

On the right-hand side as you look down to the bridge was the notorious Alsatia district, a haven for criminals where the authorities feared to tread, and the Bridewell. Built as a royal palace under Henry VIII, after 1556 it became a prison for vagrants, disorderly women and petty criminals until it was closed in 1855. The gatehouse of 1808, improbably elegant for such an institution and the only remains of the Bridewell, is a short way down the hill at No. 14.

Priscilla Wakefield says, ‘Many of the prisoners, whom we were permitted to see, were women, young, beautiful and depraved.’ These were part of the army of prostitutes who scraped a living in London, many of them girls who had been dismissed from more respectable employment after becoming pregnant.

Jane was well aware of the dangers to innocent young women from procuresses. In September 1796 she wrote to Cassandra joking of the dangers of finding herself alone in London. ‘I should inevitably fall a Sacrifice to the arts of some fat Woman who would make me drunk with Small Beer.’

Nor does she flinch from discussing the dangers that awaited young women who ‘fell’, such as the daughter of Colonel Brandon’s sister-in-law, in Sense and Sensibility. The Colonel tells Elinor, ‘He had left the girl whose youth and innocence he had seduced, in a situation of the utmost distress, with no creditable home, no help, no friends …’ Fortunately Brandon rescues her or she could have ended up in a place like this. No wonder the Bennetts were so desperate to find Lydia when she ran away with Wickham in Pride and Prejudice.

From Ludgate Circus walk up Ludgate Hill turning into Limeburner Lane, the first street on the left. This follows the south-eastern boundary of the Fleet Prison, and the curve retains the shape of the prison’s walls. Conditions in the Fleet, which dated back to the twelfth century, were dreadful, even after it was rebuilt in the 1780s. It was finally closed in 1842.

On the right is the site of Belle Sauvage Yard. The Belle Sauvage was rebuilt by 1676 after the Great Fire and throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth century was one of the principal coaching inns in the City, with stables for over one hundred horses. Coaches departed for Bath, Cambridge, Cheltenham, Hastings, Leeds and many other destinations and it became a tourist attraction to watch them leave. The inn was demolished in 1873.

The Old Bailey in 1814. The Sessions House is on the right with Newgate Prison beyond it. Opposite was St Sepulchre’s Church, whose bells were tolled as prisoners were led to their execution. Next door to the church was the house of the notorious thief-taker and criminal, Jonathan Wild.

A cell door from Newgate Prison, on display in the Museum of London.

Turn left into the Old Bailey, which brings you to the Central Criminal Courts (1907). This occupies the site of Newgate Prison, another fearsome gaol dating back to the early Middle Ages. A new prison was built (1770–8) and rebuilt (1780–3) after the Gordon Riots, with the Sessions House beside it and an area in front for the vast crowds who gathered for public hangings.

Priscilla Wakefield smugly informs us:

Humanity pointed out the disadvantage of conveying the wretched sufferers so far from their prison to be put to death; and the use of the gallows [at Tyburn] was laid aside for a new invention, placed on the outside of the prison at Newgate; for in this happy country no capital punishment can be inflicted privately.

The area teemed with spectators during executions, and viewpoints at nearby windows commanded premium prices. In 1807 the crowd was so great that panic set in and twenty-seven people were killed.

For magistrate Henry Fielding, Newgate was, ‘a prototype of hell’ and the posies of flowers that the judges at the Central Criminal Courts still carry on ceremonial occasions were originally an attempt to ward off the appalling stench of the place.

St Paul’s Cathedral in 1814.

The dramatic memorial to Sir William Ponsonby in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral. He was killed at the battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815.

Despite the grim surroundings – or perhaps because of the excellent business during court sittings and public hangings – the Old Bailey had numerous eating places, including William’s boiled beef shop serving Georgian fast food, the ‘hasty dinner’.

Return down Old Bailey to Ludgate Hill and continue to St Paul’s Churchyard, the traditional location for booksellers and printers. It was to his uncle Stephen Austen’s shop here, ‘at the sign of the Angel and Bible’, that Jane’s newly orphaned father George was sent in 1737, with his two little sisters. They were received ‘with neglect, if not with positive unkindness’, he later recalled.

The Cathedral has numerous monuments of Georgian interest. Amongst the memorials in the main body of the building are many dating to the war with France, including the admirals Collingwood and Howe. The artist Turner is also buried here. In the Crypt are the massive tombs of Wellington and Nelson.

City street names frequently reflect the trades that were carried on there in the Middle Ages.

There is free entrance on the north side to part of the Crypt with loos and a café. Almost opposite this entrance is the re-sited Temple Bar, placed here in 2004.

Leave the cathedral and walk along its northern side to reach New Change. At this point it is possible to make a detour up St Martin le Grand to the Museum of London. The Modern galleries at the museum cover the eighteenth century onwards, and include a door from Newgate and artefacts including a fan celebrating George III’s escape from assassination at Drury Lane Theatre (Walk 7) and one of John Manton’s duelling pistols (Walk 3). It is possible to cover the eighteenth century and Regency area in an hour, but allow much longer for the whole museum. There is a café and a shop with a good book section.

A London merchant couple in their modest but respectable clothes, portrayed by a French artist in 1804. A ship, the symbol of trade, sails on the Thames behind them.

To continue on the main route, cross to Cheapside, the street that the Bingley sisters laugh about so snobbishly in Pride and Prejudice when they discover that the Bennett girls have an aunt and uncle living in the City.

‘If they had uncles enough to fill all Cheapside,’ cried Bingley, ‘it would not make them one jot less agreeable.’ ‘But it must very materially lessen their chances of marrying men of any consideration in the world,’ replied Darcy.

For all the sneers it was actually a very prosperous and respectable commercial and shopping area.

On the right-hand side is the Wren church of St Mary le Bow. Tradition has it that to be considered a Cockney a Londoner must be born within the sound of its bells.

Lions guarding a heap of coins on one of the Bank’s external walls.

Cheapside becomes Poultry, which was the location of the ancient King’s Head Tavern. It was famous as the principal turtle depot, with tanks of them in the courtyard, ready to be sent out to make luxurious soup. Elizabeth Fry, the prison reformer, lived at St Mildred’s Court at the end of Poultry, almost opposite Mansion House, official residence of the Lord Mayor since 1752.

The George and Vulture.

Cross to Threadneedle Street and the Bank of England looms on your left. Built in 1788 by Sir John Soane, only the great outer wall remains of his design: the interior was rebuilt in the twentieth century.

Turn left into Bartholomew Lane to the entrance to the Bank’s museum. There is plenty for the Georgian and Regency enthusiast to enjoy, from coins and banknotes to cartoons.

Continue your walk by crossing Threadneedle Street, through Royal Exchange Buildings to Cornhill. Cross Cornhill and turn left to the narrow entrance of Ball Court.

Modern Fish Street Hill.

Here Simpson’s Tavern occupies two dwelling houses of the seventeenth century that were converted into a chop house in 1757. Continue past Simpson’s to Castle Court. To the left is the George and Vulture, built in 1748. It was here that Sir Francis Dashwood founded the Order of the Knights of St Francis of Wycombe, popularly known as the Hell Fire Club. It was notorious for heavy drinking and sexual debauchery and also for radical politics – Benjamin Franklin visited Dashwood in 1774, although whether he partook of the Order’s activities is not recorded.

In 1812 Fish Street Hill plunges down past the Monument, under the clock of St Magnus the Martyr and straight onto Old London Bridge.

Turn right to Birchin Lane, which leads to Lombard Street; then turn left into Clement’s Lane. St Clement’s Church is probably the church where Lydia and Wickham were married in Pride and Prejudice, although St Clement Danes is also possible. However, this church is just around the corner from where her aunt and uncle lived.

We were married, you know, at St Clement’s, because Wickham’s lodgings were in that parish. And it was settled that we should all be there by eleven o’clock. My uncle and aunt and I were to go together; and the others were to meet us at the church.

Then Lydia reveals that Mr Darcy was there also, throwing Lizzie into confusion.

From Clement’s Lane bear left to the corner of Gracechurch Street, home of the Bennett girls’ Uncle and Aunt Gardiner. ‘Mr Darcy may have heard of a place called Gracechurch Street, but he would hardly think a month’s ablution enough to cleanse him from its impurities.’

Old London Bridge from the Southwark bank. The tower of St Magnus the Martyr and the Monument dominate the skyline.

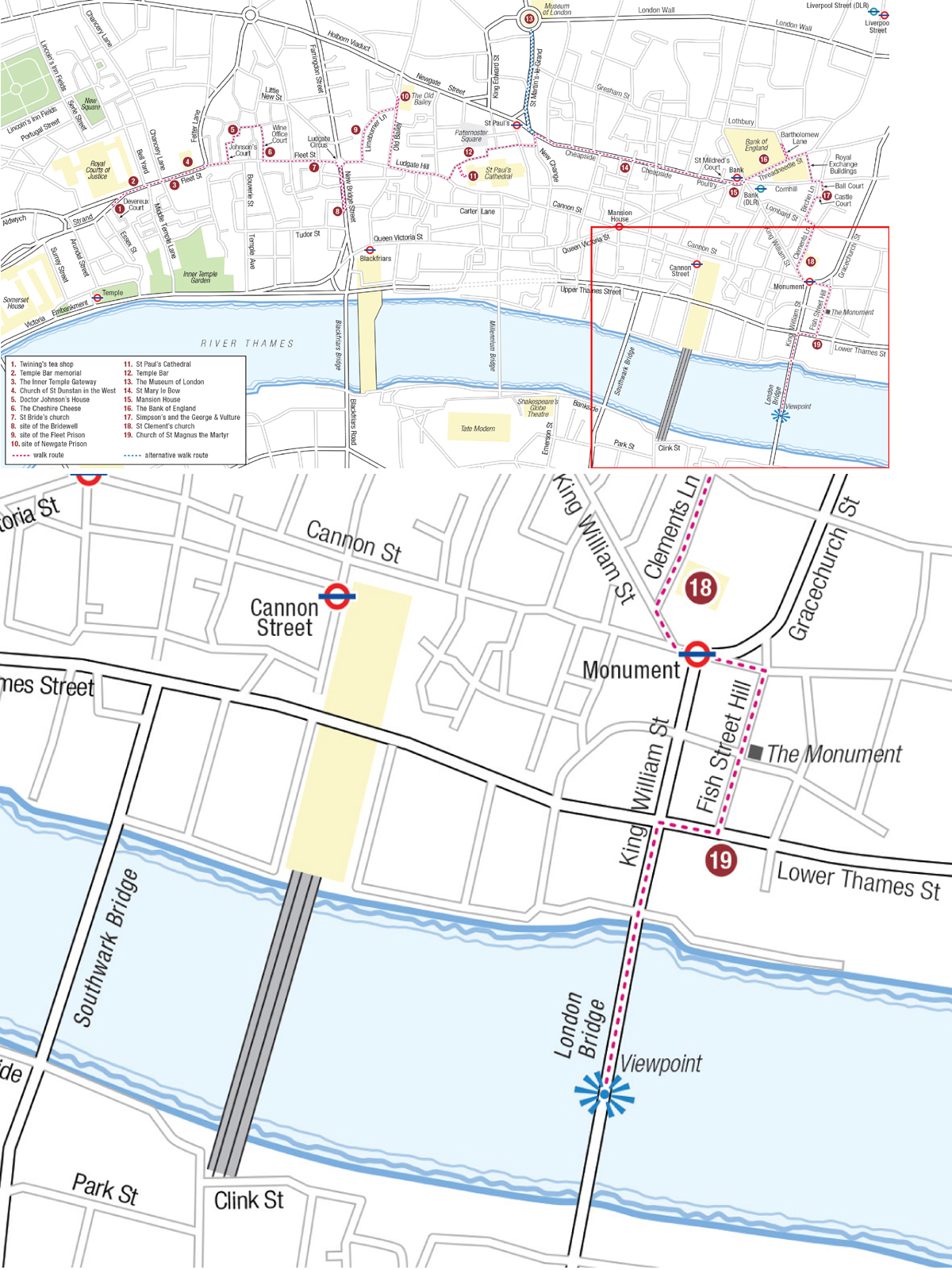

Cross the road and walk down Fish Street Hill past the Monument. This was the bustling thoroughfare that ran down to London Bridge before the old bridge was demolished in 1831–3. At the bottom is Lower Thames Street and the church of St Magnus the Martyr: its large clock, which seems so awkwardly placed now, actually overhung the roadway of Old London Bridge.

Turn right and immediately under the modern bridge are steps up to the top. Old London Bridge was just downstream of the present bridge. At the site of the new bridge there was a waterworks with waterwheels taking four million gallons a day from the river to supply ten thousand customers.

Although it was shorn of its famous buildings, and had been widened and refaced in the mid-eighteenth century, the bridge when Jane knew it was still the famous structure of the nursery rhyme.

It was so narrow that traffic jams were common. As a result there were many coaching inns south of the river in Borough High Street where passengers could change to more convenient transport.

The bridge was constantly under repair. It was severely damaged in the winter of 1813–14 when the last frost fair was held on the river; work on its replacement was begun in 1824. The current bridge, where we end our walk, was opened in 1973.