|  |

ANCIENT HELLAS WAS never what one might call a peaceful land. Dotted with numerous poleis great and small, all vying for their own place in posterity, building alliances and sundering them, Hellas was a landscape rife with wars both petty and ambitious. Over time, the habitual bloodshed forced many cities to develop strategies for the protection and evacuation of non-combatant citizens. If siege appeared imminent, the civilian population of a city was generally sent to allied poleis for protection; in some extreme instances a city might be entirely abandoned in the short term, as with the evacuation of Athens during the Persian Wars. While this strategy was effective in preserving the core population of a city, the result was an almost constant movement of refugees across the landscape, either seeking sanctuary or— if they were lucky— returning to reclaim their homes. Despite this fact, little notice is taken of refugees once they have fled their home city; the ancient sources typically stop at the very point where the stories of the refugees begin. In this book we will study the phenomenon of refugees in Late Classical and early Hellenistic Greece, particularly Athens, and examine the experience of refugees and their host poleis.

The lives of refugees while in exile are very poorly documented by contemporary authors. The Plataeans’ flight to Athens during the Peloponnesian war is narrated by Thucydides in the context of the Spartan siege (2.78, 3.23), as is their resettlement at Scione, but not their activities when in residence at either location. Lysias’ speech Against Pancleon provides a few details concerning Plataean life in Athens, but only as tangential elements to his case. The flight of Olynthian refugees after the destruction of their city is not recorded by authors of the time at all. Instead, contemporary accounts, such as those offered in the speeches of Demosthenes, focus on the Olynthians who did not escape and were either killed or sold into slavery. This narrowness of Demosthenes’ focus is easily explained by his agenda. The destruction of a once powerful city and near annihilation of its population, provided excellent fodder for Demosthenes’ speeches against Philip, the implication being that this fate would befall Athens should some action not be taken. Surviving refugees added little to such a dramatic narrative and therefore were not discussed; this pattern is typical of the treatment refugees received from historians What knowledge is preserved regarding the activities of those who escaped is derived from inscriptions and much later— and therefore suspect— accounts such as the 10th-century Suda. When examined together, however, the various classes of information— epigraphic, historical and anecdotal— allow one to draw a general picture of how refugees chose their destinations, how they were provided for in their temporary homes and how refugee and host populations negotiated the tricky business of living together while living apart.

Modern Refugee Policy

Before any discussion of refugees is possible, it is necessary to define what is meant by the term “refugee,” a task complicated by an imprecision of language in both the ancient and modern sources. According to Article 1a of the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees:

[T]he term “refugee” shall apply to any person who... owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, unwilling to return to it.[1]

This definition of refugees reveals the fundamentally humanitarian base upon which modern refugee theory and policy are built. The definition was arrived at due to the events of two World Wars and numerous other revolutionary conflicts, in Europe especially, which saw the mass migration of people within Europe and outward into the Americas. Before this 1951 convention, who was granted the title of refugee— and therefore eligible for aid—was determined by the individual treaties and accords ending whichever war had displaced the people involved.[2] While many modern countries adhere to the UN definition of refugees, several have their own definitions and terminology for people who have been forcibly evicted from their homes; some of these titles include “asylum-seeker,” “stateless person,” “exiles,” “expellees” and “transferees.”[3] The plurality of names and definitions for refugees is due to the context in which modern refugee policy and theory developed.

Modern refugee policy arose from the efforts of Allied forces to manage, care for and resettle the vast numbers of men, women and children left homeless by World War II. The model for modern refugee camps and their administration was largely based upon attempts by military bureaucracy to house, feed and provide medical care for refugees awaiting repatriation or resettlement.[4] Fear of what might happen should refugees be left to their own devices appears to have been the major motivation behind the military’s actions. A special division of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), known as the Displaced Persons Branch, argued that:

The problem of displaced persons is likely, within a matter of days, to assume vast proportions before the ground organization for dealing with it is fully established... [U]ncontrolled self-repatriation of displaced persons who might form themselves into roving bands of vengeful pillaging looters on trek to their homes... would endanger millions of Allied nationals [whose] fate will be regarded as a gauge of Allied capacity to deal effectively with major European problems.[5]

To prevent this eventuality from occurring, SHAEF utilized abandoned military, work and concentration camps as staging points for housing and processing refugees before attempting repatriation or resettlement. It also partnered with non-governmental aid organizations, like the Red Cross, to assist in the provisioning and maintenance of refugees during their stay in the camps.[6] This procedure of relocating refugees to centralized camps and assisting them primarily through the efforts of voluntary aid groups became the standard for handling large groups of refugees.

With the passage of the 1951 Geneva Convention regarding refugees, a single supra-national agency was established by the United Nations to oversee issues of refugee assistance, resettlement and legal status in host countries— the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. In recent history, most of the operations of UNHCR have taken place in third-world countries on account of economic and political instability related to de-colonization.[7] Thus, the term “refugee” has become linked with an image of people in third-world countries fleeing war and persecution with little more than the clothes on their backs, for example the Rwandan refugees who fled to camps in the Congo beginning in the 1960s and continuing through the 1990s.[8] Thus the concept of the “refugee” has become associated with notions of economic disadvantage and social marginalization. In 2005, the Rev. Jesse Jackson said in an Associated Press interview about the Hurricane Katrina evacuees, "It is racist to call American citizens refugees," because of the implication of second-class citizenship.[9]

Over time, organizations which assist refugees have broadened their mandates to include casualties of natural disasters, like the Hurricane Katrina evacuees and the victims of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti; because these groups do not fit the classic definition of a refugee as put forth in 1951, theorists have suggested new labels for these people: so-called internally-displaced persons or ecological refugees. The broadening of the definition of “refugee” to include people affected by non-human events and the emphasis placed on refugees in the third-world has led to a shift in refugee policy from reactionary measures to assist refugees once they have fled their home, to pro-active attempts to prevent the creation of refugees in the first place.

Whereas the policy toward post-WWII refugees focused predominantly on re- settlement in new countries, shaped in large part by the debate concerning accommodations for the Jewish victims of Nazi Germany[10] and the necessity to find new homes for refugees of the new communist regimes in Eastern Europe,[11] refugee policy since the 1990s has focused on repatriation and reintegration of refugees as soon as is practicable; this policy, though, has had unintended consequences. Often the governments or individuals from whom refugees have fled retain power for decades, preventing the timely repatriation of refugees. As a result, refugees become semi- permanent residents of what were intended to be temporary aid camps. One example of this kind of camp is the Liberian refugee camp at Buduburam, Ghana, created by the United Nations in 1990 and still operational over 20 years later. These long-term camps often become de facto cities; the Buduburam camp has evolved into a semi-permanent settlement housing almost 42,000 people and has its own market, elected officials and new residents still periodically arriving.[12]

The existence of these long-term camps has resulted, in many cases, in unfavorable attitudes toward the refugees who inhabit them. In the late 1990s, Kenyan refugee camps saw a major increase in violence because of, among other factors, banditry caused by inadequate rations, inter-ethnic clashes, and domestic violence.[13] The threat of spill-over violence together with concerns regarding the availability of arable land caused Kenya to become wary of large influxes of refugees. Moreover, Kenyans residing in Mombasa came to view the refugee camps as a source of economic insecurity. Business transactions conducted in the refugee camps were not subject to taxation as were those conducted in the city of Mombasa, providing an advantageous climate for the refugees and enterprising merchants. The imbalance led members of the Mombasa business community to pressure the government to disband the camps and move the refugees, which it did.[14]

Another effect of long-term residence in the camps is that refugees occupy a grey area of the law. Not officially immigrants or asylum seekers, many refugees do not hold any legal status or identification documents. Refugees are often viewed strictly as a humanitarian issue and therefore the responsibility of UNHCR or its equivalent.[15] The UN may provide guidelines and pass resolutions regarding the rights of refugees, but the adoption of such measures is purely voluntary. The ambiguous legal status of refugees leaves them open to extraordinary measures on the part of the host country, such as forced repatriation or police harassment. These experiences can result in the creation of “refugee warriors.”[16] Young men disillusioned by life in the camps provide fertile recruiting ground for the militaries on one side or the other of the conflict which forced them from their homes originally.[17]

Modern refugee policy is based on humanitarian principles and underpinned by moral imperatives. The structure of modern refugee management developed after World War II and calls for the centralization of refugee groups into camps which are overseen by international refugee relief organizations like the UNHCR. Food, housing, medicine and infrastructure in the camps are largely dependent upon NGOs and donations made to the Red Cross and similar independent aid organizations. Although these camps are designed to be temporary establishments, the pursuit of a policy focused on repatriation has made many refugees long-term denizens of them. Long- term refugee camps have, in turn, given rise in certain cases to hostility toward refugees who are blamed for increased violence and economic disadvantage among the host population. Given these circumstances, refugees are often viewed by society in diametrically opposed lights— either refugees are victims of social injustice dependent on the generosity of others or refugees are a potential threat to the physical and economic security of host nations and to be viewed with suspicion.

Modern Refugee Theory

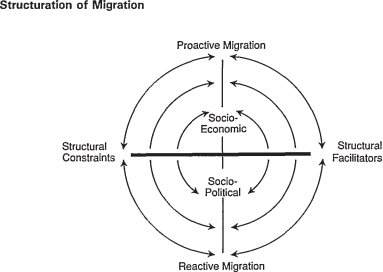

The field of refugee studies is still relatively new. Until the 1970s and 1980s, refugee theory was largely a by-product of refugee policy and was concerned predominantly with questions of how and when refugees should be aided, resettled and assimilated, rather than questioning the processes of resettlement, acculturation and assimilation. As the field of identity studies gained momentum in the 1990s, theorists began to examine the motivations for and methods by which refugees, migrants and immigrants chose to retain aspects of their previous cultures and identities in their new contexts and what if any characteristics of their new society they accepted. These inquiries required per force that theorists examine the reasons for a new arrival’s migration as a contributing factor to identity retention or loss. Consequently, new categories of migrants and migration were developed. Previously, migrant peoples had been categorized as “voluntary” (for example early twentieth-century immigrants to the United States seeking economic opportunities) or “involuntary” (such as the refugees of WWII). Instead, Anthony Richmond (1993) proposed a new model of migration which placed migrants on a sliding scale of “proactive” and “reactive” migration. This model is much more detailed, taking into account predisposing factors for migration, political, social and economic constraints on migration as well as the initiating events. Migrants are located on the spectrum based upon the reasons for migration, facilitating or restricting factors and the precipitating event. For example, in Richmond’s model, professional migrants (such as lawyers, doctors and engineers), temporary workers and “anticipatory” refugees— people who are motivated to leave their homes for political reasons, but whose lives are not as yet directly threatened— would be located somewhere along the proactive end of the spectrum. Reactive migrants would be people to whom the UN definition of a refugee apply who have been driven from their homes by force or threats of violence.[18] Using this model, Richmond has developed a typology of reactive migration which takes into account multiple contributing factors for migration. Richmond’s model of migration can be used to analyze the flight of refugees, whether they behave as proactive or reactive migrants and further determine what typology might apply to ancient refugees who appear to fall on the reactive end of the spectrum. Once refugees are identified as proactive or reactive, further examination might reveal whether there is a correlation on the part of host communities’ treatment of refugees and their status as proactive or reactive migrants.

Fig. 1. Structuration of Migration (after Richmond, "Reactive Migration: Sociological Perspectives on Refugee Movements." Journal of Refugee Studies 6.1 (1993), p.11. Reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press.)

To examine how refugees incorporated themselves into their host communities, John Berry’s (1997) work on acculturation among immigrants is useful. He discusses how immigrants decide what of their original culture and identity to retain, and in what context (private in the home or publicly in interactions at work and the community) they display it. Berry examines acculturation on the group and individual level and rightly points out that individuals within a group might integrate into the society of their hosts in varying degrees in relation to the group as a whole. Berry’s analysis also takes into account incentives and barriers to acculturation created by the host community. Berry also distinguishes among acculturation and interculturation.[19] Whereas acculturation indicates a change in the original culture of either of the refugee or host population (though normally the refugee population) brought about by their contact with each other, inter-culturation is “the set of processes by which individuals and groups interact when they identify themselves as culturally distinct.”[20] Much of Berry’s work is based upon the actions and reactions of refugees living in multi-cultural societies, a situation that did not necessarily exist in ancient Greece, but the broad framework of Berry’s analysis might still prove useful in analyzing the interactions of refugee and host populations.

Finally, Val Colic-Peisker and Farida Tilbury discuss the level of refugee engagement in their own resettlement. They categorize refugees as “active” or “passive.” Refugees categorized as “active” in their resettlement possess a generally positive outlook on their experience and the possibilities open to them in their new homes. Active re-settlers are often anticipatory refugees who fled before they were forcibly displaced; they also employ multiple strategies to transition into their new society by taking language courses or pursuing higher education in an effort to secure more rewarding jobs.[21] “Passive” re-settlers, by contrast, “often perceive their pre- migration experiences of loss of family members, property and social status as irreparable... [T]heir emotional resources and coping ability may have been seriously depleted.”[22] Passive re-settlers often are to be found living in a state of marginalization from society, residing in ethnic communities or neighborhoods, dependent on a small network of friends and family and often refusing to learn the local language if it is different from their native tongue. Colic-Peisker and Tilbury found that the incidence of passive re-settlers in their study appeared to be tied in part to the role of aid agencies which viewed the refugees as victims. Over time, refugees who adopted this view of themselves stopped attempting to integrate into society and in some cases became dependent on aid societies for their maintenance. Although aid programs played a part in the creation of a passive mentality among refugees. Colic-Peisker and Tilbury also noted that refugees might adopt a passive role toward resettlement due to an inability to cope with their situation.[23]

All three of these theories regarding refugees and refugee resettlement were developed in response to modern causations and pressures on refugees. They provide a means to critically examine the experience of refugees in the ancient world, but because the context in which they were developed is different, not all aspects of the theories will necessarily be relevant to the study of ancient refugees. These theories were developed in modern western societies and generally pertain to how refugees from the developing world, who possess a distinctively different culture from their hosts, adapt to resettlement. Many of these studies also work from the assumption that the host community is a plural society comprised of multiple, different culture groups. There is some question whether refugees from one ancient Greek city would possess sufficiently different customs and habits to trigger the same adaptive stresses apparent in these studies. For instance, the Plataean refugees living in Athens would have understood the Greek spoken in Athens, though they possessed a slightly different dialect.

Plataeans and Athenians worshipped the same gods, though their particular epithets and attributed might vary. On the other hand, Athens was the acknowledged artistic and cultural center of Greece in the fifth century, as opposed to Plataea, which was neither particularly large nor very cosmopolitan. The cultic rites in Athens would certainly have differed from those in Athens. The two cities used different names for the months of the year, different currency and even different forms of dress.[24] It is possible that upon finding themselves in Athens, the Plataeans might have felt much the same stresses as a third world refugee suddenly relocated to the United States or another modern western country. Using the framework provided by these studies it will be possible to discuss the experience of refugees and refugee policy in fifth- and fourth-century Greece in comparison to the modern western world.

ὁ Φυγάς

Unlike modern countries, the ancient Greeks possessed a single word for refugee, ὁ φυγάς. The simplicity of this single term is belied, however, by the fact that it was used not only to refer to refugees of war, but also political exiles and criminals barred from their home city, thus once again introducing ambiguity into how a refugee should be defined. For Greeks, ὁ φυγάς might be a wealthy, internationally connected politician—such as the Athenians Alcibiades and Themistocles— who ran afoul of the current political regime. Alternatively, he or she might be a poor dirt farmer escaping an invading army with his or her family or a refugee could be someone driven from his home because of a crime he had committed and forced to seek asylum in another polis.

This usage perhaps suggests a correlation between the groups in the ancient Greek mind which does not apply in modern terminology. It is possible that the war refugee was considered to have consciously severed ties with his city himself and not merely to have been a victim. If so, refugees forced from their cities who intended to return home might be expected to employ a range of behaviors to reinforce their identity with the abandoned polis despite efforts on the part of a host city to integrate them. On the other hand, a refugee may have been viewed as unworthy of citizenship in some manner because he failed to protect his city, resulting in a prejudice toward refugees among the host population. While the ancient Greeks did not distinguish between political exiles and war refugees terminologically, in practice one might expect a considerable distinction between the two groups. Not only might the reasons for flight affect a person’s or group’s reception, but the number people petitioning for asylum could have considerable bearing upon how refugees were treated. It is much easier to accommodate an individual or small group of political dissidents sympathetic to one’s own policies than several thousand people displaced by war.

Political Exiles

The study of political exiles in ancient Greece is, of course, heavily weighted toward Athens and its procedure of ostracism. As articulated by Sara Forsdyke, exile was a tool of the aristocracy during the seventh and sixth centuries, used to remove rivals from the city and consolidate power.[25] But the mass expulsions which could occur were rarely decisive; exiled elites often would use their period of exile to gather resources and allies in other poleis for the purpose of returning home and deposing their enemies by force. The institution of democracy in Athens changed mechanisms of exile. By giving the demos as a whole the responsibility for deciding who was a threat to the city and limiting the potential frequency of an ostracism to once a year, the people presented a united front toward the exile and decreased the number of political exiles living outside Athens at any given time. This reduced the chance that exiles might be able to gather in sufficient numbers and use factions within the city to return by force.[26] The final and most important aspect in how the experience of political exile changed was the fact that the period of ostracism was term-limited, the ostracized’s property was not confiscated and he did not lose his citizenship irrevocably. Men who had been ostracized might go into exile in a friendly city (e.g. Themistocles at Argos) and there live comfortably on the proceeds of their property and businesses back in Athens. Though the exile experienced a very real loss upon being ostracized, it was tempered by the knowledge that eventually he would be allowed to return home and resume his place in civic life.[27]

How far the experience of exiles from other cities matched that of exiles from Athens is not entirely clear. Diodorus Siculus (11.86.87) reports that Syracuse in the fifth century possessed a similar system of ostracism, called petalism, in which the individual was exiled for only five years instead of ten as in Athens. Ostraca have also been found in other cities around Greece, but not in numbers large enough to indicate a habitual practice of ostracism.[28] Sparta did practice exile in some form, particularly the exile of kings who misbehaved. The expulsion of Leotychides II (which occurred c. 476, in the same period of many of the events considered in this work) is a good example of how exile seems to have been managed in Sparta. Much like an Athenian exile, Leotychides was allowed to leave Sparta and set up shop in Tegea, an allied polis. He appears to have remained king, in title at least, though his house in Sparta was destroyed (Hdt. 6.71-72). The Spartans also practiced ξενηλασία or the expulsion of foreigners, though it looks to have been tied to specific circumstances (the expulsion of Athenians on the eve of the Peloponnesian War [Thuc. 1.144.2]) rather than a general policy.[29] In fifth-century Teos, exile was the proscribed penalty for men convicted of corruption while serving as a public magistrate, while in Halicarnassus violators or opposition to any public decree or law were subject to exile.[30] It is not known, though, what further action may have been taken against the exiles.

One might surmise that exiles chose their city of destination based upon previous ties. Many of the men exiled from Athens were either proxenoi or benefactors for other poleis. A proxenos was a man appointed by a polis other than his own with the expectation that the man granted this honor would champion the interests of the foreign city in his own.[31] Proxenoi, as might be expected, appear to have been chosen from among the upper echelons of society, men who possessed the wealth and political consequence to be an asset. Several proxeny decrees from Athens were made to individuals who had given gifts of grain to Athens at their own expense during shortages, an expensive undertaking.[32] Themistocles was a known benefactor or euergetes of Corcyra, where he took up residence at one point during his exile. Though it is not known where Cimon settled during his abbreviated exile, he was a proxenos for Sparta in Athens before his ostracism and it stands to reason that he might have sought refuge in one of the cities belonging to the Peloponnesian League.[33]

If an exile did not possess previous ties to a chosen destination, he might expect to be designated a metic.[34] Metics occupied a specific place in the social hierarchy of a Greek polis. In fourth-century Athens, any xenos - or foreigner- who came to the city was allowed to reside there for a certain number of days without being required to pay taxes. Once this grace period was over, the xenos became a metic and subject to special taxes including the metoikion, or metic-tax.[35] Metics did not have access to the same justice system as citizens. Instead, they were the responsibility of the polemarch, a special official who dealt solely with court cases involving non-citizen residents of Athens. Additionally, metics could not represent themselves in court and relied upon the representation of a prostates.

Exiles differed from war refugees in several pertinent ways. Exiles along the Athenian model knew from the outset that their period of ostracism was finite. Often, the ostracized men already possessed foreign ties, such as Cimon and Themistocles, that could be exploited for relocation purposes. Should the exile be prominent enough in his new home, like Themistocles, he might receive certain benefits associated with his role as proxenos or benefactor. Finally, and crucially, exiles were not usually subject to confiscation of their property. They may have been barred from the polis of their citizenship for a time, but their financial property interests would still be protected and available to maintain the ostracized in exile. In addition, exiles still possessed some measure of protection from their city of origin, though decidedly retroactive, in that anyone accused of killing an Athenian exile outside the borders of his home polis was subject to prosecution in his home city.[36] By contrast, a refugee existed in a much more fluid state.

Refugees

Given the disparity between ancient and modern definitions of refugees, it is necessary to first define what is meant by the term in the context of this work. Ancient authors used the term ὁ φυγάς to discuss political exiles as well as forcibly displaced people. This book is not concerned with political exiles and ostracism in the Classical period; the topic has been well and thoroughly discussed. We do not intend to retread these already well-researched topics. Instead, we study large groups of citizens forced from their home polis due to warfare, not normal political processes or natural disaster. We have chosen this topic for two reasons. First, it is easier to determine the reason for flight in primary sources when large groups of refugees are involved rather than individuals. Second, an individual exile arriving in Athens or elsewhere could easily be accommodated by inclusion in the pre-existing metic population, a topic that has been treated before. On the other hand, the arrival of several hundred or thousand refugees would have required a much more elaborate response including the allocation of resources and housing. Previous studies have touched lightly upon certain aspects of the refugee experience, but no comprehensive study has been made. M.J. Osborne, in his Naturalization in Athens, and Mirko Canevaro’s work on Plataean enfranchisement in Athens discuss grants of citizenship to refugees among others.[37] Kulesza, in his article "Population Flight: A Forgotten Aspect of Greek Warfare in the Sixth and Fifth Centuries B.C."[38] discusses the mechanics of flight, but does not discuss the implications for those who fled. One of the objectives in this book is to determine, so far as possible, how poleis responded to the arrival of large groups of refugees. This investigation will, by necessity, be rather Atheno-centric due to the available sources; however, this focus is not without benefit. Athens enjoyed (and promoted) a reputation in the ancient world as a place of solace and safety for exiles and refugees.

Evidence for Athens’ propensity to aid dispossessed people is found not only in Athenian drama, such as Euripides’ Children of Heracles, but also in later Roman authors such as Statius who memorializes the Athenian cult of Eleos, the goddess Mercy, at whose altar fugitives and refugees might find sanctuary. The willingness of Athens to accept and assist refugees may stem from the fact that the Athenian populace had itself been refugees once. The evacuation of Athens before the Persian army in 480 B. C. was an enduring memory for Athens, tied as it was to the defeat of the Persian navy at Salamis. The legacy of their time as refugees in Troezen, and on Aegina and Salamis was played out over the course of two centuries as the Athenians repeatedly offered reprieve for men and women forced from their homes. Based upon Athens’ example, a general pattern of action may be deduced which can then be used to examine the fragmentary evidence available from other cities.

In this work we will be use numerous types of evidence including epigraphic sources— in the form of grave stelae, honorary inscriptions and treaties— and archaeological evidence from several excavations across Greece. This approach is necessary due to the paucity of information regarding refugees in any one field of evidence. While literary accounts, such as Thucydides’ narration of the Plataean flight and settlement in Athens, provide the most direct evidence for refugees, inscriptions are a significant portion of the evidence for refugees in Athens and elsewhere. Olynthian refugees, for example, are almost exclusively documented epigraphically rather than by the historians or orators. Furthermore, while the flight of the Tirynthians is recorded in the historians, almost all evidence for their existence at Halieis comes from excavations conducted in the 1960s and 1970s.

This approach is not without complications. The identification of refugees via inscriptions is largely dependent upon the use of what Hansen terms a “city-ethnic.”[39] The general formula for naming in fifth- and fourth-century Greece consisted of two or three parts- an onoma (or personal name), a patronymikon (the father’s name) and, in some instances a demotikon. The demotikon is a sub-ethnic which, when used by a citizen in his own city, indicated membership in a particular demos (municipality), genos (clan), or phratry (brotherhood). But, when a man was residing in a foreign city, an ethnikon indicating his polis or region of origin was substituted in place of the demotikon. Thus in Athens, non-citizens are regularly denoted both in inscriptions and legal arguments by their onoma, patronymikon and ethnikon. Outside Athens, the same generally holds true, however, in cities where the use of a sub-ethnic such as a demotic is not common, there is likewise a lack of foreigners attested by city-ethnics.[40]

The use of a city-ethnic must have been at its core an attestation of political identity rather than merely a geographical locator or address of sorts. The use of a city- ethnic was restricted to the citizens of that city; there are no attestations for slaves who came from Athens or metics who lived there being addressed as an Ἀθηναῖος. City- ethnics are routinely used in public documents to refer to a city.[41] In the Athenian tribute lists of the fifth century, Olynthus is not listed by its toponym, but by the plural city ethnic Ὀλύνθιοι. This practice illustrates the Greek conception of a polis; it was at its root the sum of its citizens, not the physical city itself. Later, in treaties between the Chalcidian League and various Macedonian kings, the federal ethnic Χαλκιδεῖς is also used. This notion of people-as-polis is particularly relevant to refugee studies in the ancient world as it helps to explain why refugees, like the Olynthians, could retain the use of their city-ethnic long after the destruction of their city. So long as a core group of (purported) citizens existed, there was the theoretical possibility of rebuilding the polis. An extreme example of this mind set can be seen in the (re)founding of the polis Messene by Epaminondas in the fourth century, several hundred years after the Messenians had first been conquered by Sparta.

Over time the political identification of a refugee might eventually become a facet of personal identity. The descendants of Olynthian refugees continued to identify themselves with their lost polis even into the first century B.C. long after any hope of rebuilding the city had passed and they had been scattered around the Hellenistic world; the Olynthian ethnic is found in inscriptions from around the Aegean and in Asia Minor.[42] Also, several sepulchral inscriptions of women from mid-fourth century Athens bear the ethnic Ὀλυνθίη or Ὀλυνθία.[43] Since citizenship was restricted to males, one would not expect to find a woman using a city-ethnic. But it is clear that these women, and their relatives, living (and dying) as resident aliens have co-opted an essentially male prerogative as a part of their public face. When deprived of their cities, refugees continued to use their ethnics as a means of separation and distinction from their host communities and to maintain a link with their lost homes.

An obvious point of concern and possible confusion lies in the ability to distinguish between members of the regular Athenian metic population and potential refugees in inscriptions, since metics were voluntary residents of their host community, not displaced people, and both groups could be referred to using a city-ethnic. Since this book argues for a distinct difference in the treatment of refugees as opposed to ordinary metics, it is imperative that the two be differentiated in the epigraphic record. The identification of metics in inscriptions is, however, difficult. Metics referred to en masse only appear five times in Athenian inscriptions and individuals specifically labeled as metics only appear twice.[44] Whitehead has argued that when referred to in official documents, metics are generally identified by the phrasing “oikon en ” followed by the metic’s deme of residence. In personal inscriptions like tombstones, though, Whitehead sees the use of the city-ethnic as predominant, thus obscuring the difference between metics and foreigners who have been granted extra privileges.[45] This is why inscriptions alone are not sufficient evidence that the individual or individuals named were refugees. Corroboration must be found in the archaeological record for destruction of the home polis or literary evidence for population flight.

Once a group of refugees has been identified, it is possible to examine their reception by various cities. The evacuation of a city’s populace to an allied polis during wartime was a common strategy, however, these evacuations were normally of a relatively brief duration as with the Athenian evacuation to Salamis during the second Persian War.[46] In this instance, the evacuees were also divided into multiple groups and sent to different cities to alleviate the burden. But the massive scope and duration of conflict in the fifth century, beginning with the events of the First Peloponnesian War in 460 and continuing until 404/3, disrupted the normal pattern of evacuation and return. Cities were razed to the ground or captured and occupied by enemy forces leaving the entire population refugees with no place to which they could return. Long-term settlement of evacuees and refugees became the norm and forced poleis to devise systematic methods of accommodation.

The reception of refugees, in Athens and elsewhere, could take many forms. At Athens, one response might be the granting of isoteleis. Foreigners who enjoyed the rights of isoteleis occupied an intermediary position between a metic and a citizen. Judicially, isoteleis were still foreigners and were subject to the polemarch like metics. Financially, isoteleis were relieved of at least two of the taxes which metics were required to pay, namely the metoikion and a special market-tax on foreigners.[47] Another option for dealing with refugees might be to grant proxeny to an individual or several individuals. Though proxeny was generally given to men residing in their own polis of citizenship to act as ambassadors for the interests of another city, it could also be granted to a resident alien by the community in which he resided to act as a facilitator for any citizen of his home city who should happen to take up residence in the same community.[48] The rights and privileges of a proxenos in Athens during the fifth century are unclear. Whitehead has theorized that they would have begun in the fifth century with basic rights of exemption from taxes levied on foreigners, and by the fourth century have evolved to include all the rights enjoyed by isoteleis and enktesis. In such respects a proxenos has sometimes been compared to a modern consul or diplomat, but Greek cities did not necessarily restrict themselves to a single proxenos per polis, as is generally the case with modern consuls. In fact a single polis might be represented by multiple proxenoi in one city. For example, two Olynthians were granted overlapping decrees of proxeny in the city of Oropos near the end of the third century.[49]

The appointment of a refugee as proxenos provides a considerable amount of information as to how the host polis viewed its guests. In order for someone to be appointed a proxenos, there must have been an assumption on the part of the granting polis that the refugees still comprised an independent state. This being the case, the city could proceed to conduct normal diplomatic relations with the refugees through the proxenos. The refugees would most likely have been treated as resident aliens in the city and not subject to attempts at integration. Eventually, special dispensations might have been made concerning land ownership or taxation should the refugees stay become extended.

A third possible response to refugees might be to grant the refugees isopoliteis, equal rights of citizenship (up to a point) within the community. This type of grant was extremely rare, though, and usually only made to individuals.[50] In Athens, isopolity was an especially prized commodity. An individual granted isopolity was able to initiate court proceedings, either as a plaintiff or prosecutor, and represent himself in court proceedings without a prostates.[51] Foreign nationals granted isopolity were also exempt from the metic tax; instead they paid a significantly lower citizens’ tax. Whereas non-citizens and metics were regularly excluded from owning land in Athens, as a naturalized Athenian, people possessing isopolity would be allowed to literally buy a stake in the polis.[52] Probably the most famous example in Greek history of a group receiving such a grant is that of the Plataeans in Athens. Outside of Athens, various Olynthians were the recipients of this type of citizenship grant in Ephesos and Miletus.

Of course, these options all assume that a polis would grant the refugees asylum, an assumption that cannot be taken for granted. Unlike the modern world, which has multiple non-governmental aid organizations (such as the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies) which assist in the housing and support of refugees, any Greek polis that took in displaced people was solely responsible for their care and maintenance. The sudden influx of non-citizens requiring food, lodging and protection could be a serious drain on resources, particularly since the major Greek poleis were virtually always at war or on the brink of it. Furthermore, the acceptance of refugees might draw the anger of whoever displaced them in the first place. Given these circumstances, a city must have had compelling reasons to accept the refugees. In order to fully understand the experience of refugees in Greece and the development of responses to them, it will be necessary to also examine the political considerations involved in their welcome.

The first chapter of this book examines the two instances of Plataean refugees’ residence in Athens. It analyzes the circumstances surrounding the removal of the Plataeans to Athens and the special relationship between Athens and Plataea which led to the refugees’ reception into Athens. Relying primarily on the work of Thucydides, the Athenian orators and a few later historians, this chapter outlines the measures taken by the Athenians to accommodate the refugees while protecting the integrity of Athenian citizenship and civic life. Finally, the actions of the Plataeans while resident in Athens are considered and questions about the perpetuation of Plataean identity are discussed.

The second chapter focuses on the relocation of former Messenian slaves by Athens in the mid-fifth century. The political climate between Athens and Sparta at the time is assessed as it related to Athens’ motivations for facilitating the Messenians removal, as well as Sparta’s reasons for allowing it. Likewise, the consequences of Athens’ interference are considered in light of the Archidamean War which followed. A comparison between Athens’ treatment of the Plataeans and the Messenians is made to determine whether the two groups were treated equally or, if not, why they were handled differently.

The third chapter concerns refugees from the destruction of Olynthus. Through the study of epigraphic sources, it is determined whether a coherent strategy is discernible in the treatment of Olynthian refugees both in Athens and other non- Athenian cities. Factors governing the selection of location for refuge on the part of the Olynthians, such as proximity to Olynthus and previous diplomatic or personal ties to a city, are examined. The perpetuation of Olynthian identity after the fall of Olynthus will receive special consideration, since the persistence of the Olynthian ethnic for centuries after the destruction of the city is one of the distinguishing characteristics of the Olynthian refugees and their descendants. In her 1933 book A History of Olynthus, Mabel Gude published a prosopography of all the Olynthians named in epigraphical and literary sources.[53] Using this resource and other inscriptions discovered since, an attempt is made to trace the descendants of Olynthian refugees and study the circumstances surrounding the retention and loss of the Olynthian ethnic over the course of two centuries.

In the fourth chapter, other less well-known affairs involving refugees are considered. Events outside of Attica are evaluated such as the reception of the Aeginetans at Sparta, and the welcoming of the Tirynthians at Halies. Examination of these events in comparison with those involving the Plataean, Messenian and Olynthian illustrates the pan-Hellenic concern with housing large numbers of refugees in one’s polis and the desirability to resettle or repurpose the refugees for the benefit the host polis.